I’m not exactly sure when I decided to make a performance piece about my sister’s traumatic brain injury and death. In fact, I’m not sure there ever was a single moment of decision. Her story had become public in many ways, from online care sites to prayer chains to social media posts from family and friends. Her story was being performed out in the world before I started telling it.

Click play below to hear the author narrate the slides as you navigate.

Feel free to pause the audio at any time.

Click play below to hear the author narrate the slides as you navigate.

Feel free to pause the audio at any time. A full transcript is below.

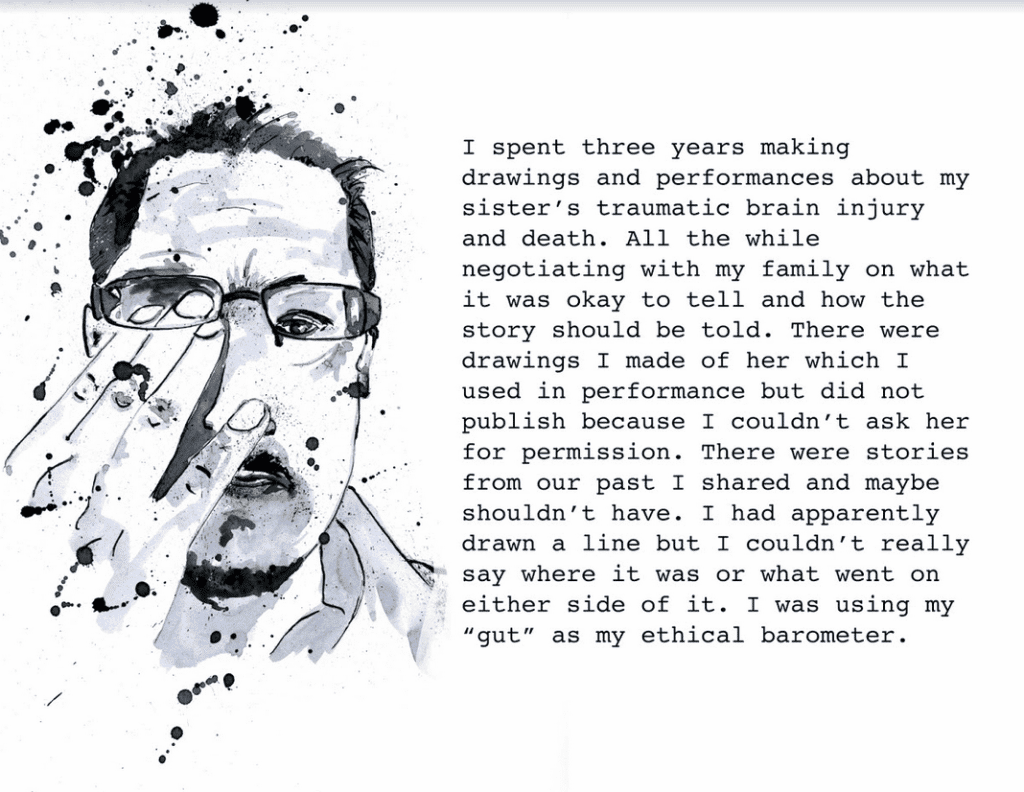

I spent three years making drawings and performances about my sister’s traumatic brain injury and death. All the while negotiating with my family on what it was okay to tell and how the story should be told. There were drawings I made of her which I used in performance but did not publish because I couldn’t ask her for permission. There were stories from our past I shared but maybe shouldn’t have. I had apparently drawn a line, but I couldn’t really say where it was or what went on either side of it. I was using my “gut” as my ethical barometer.

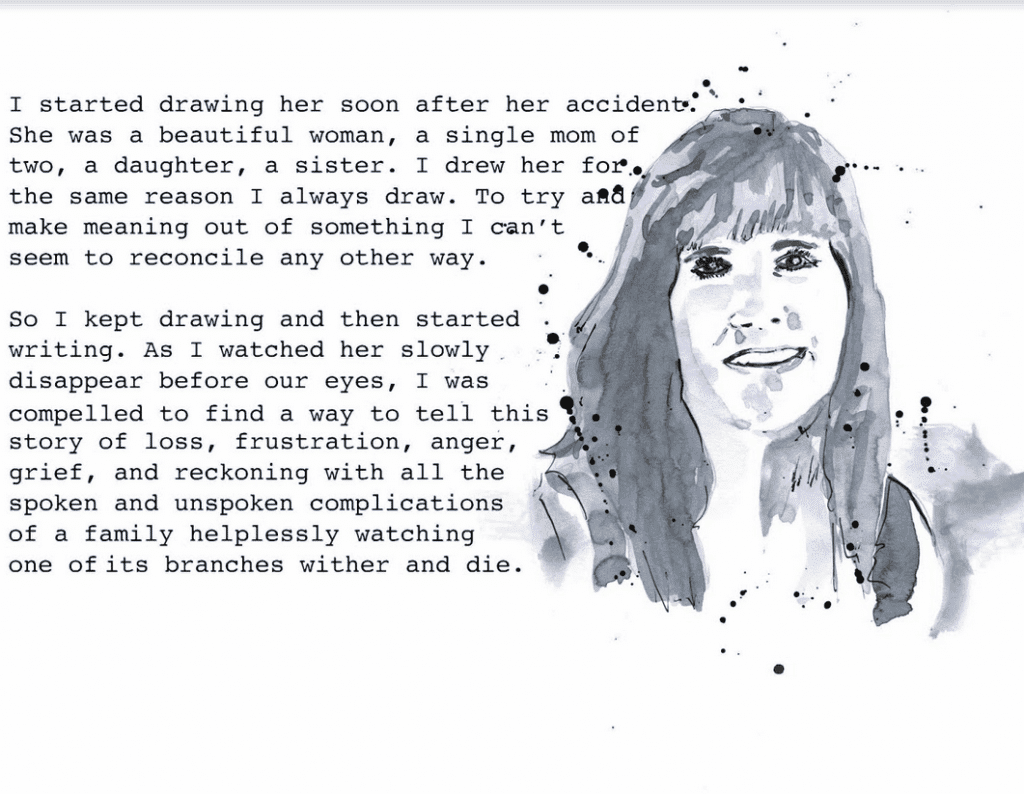

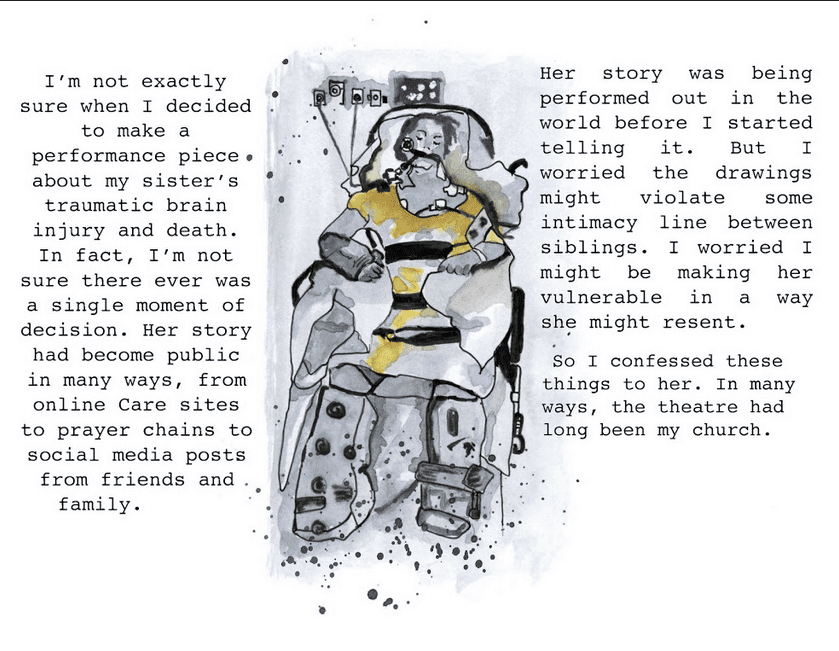

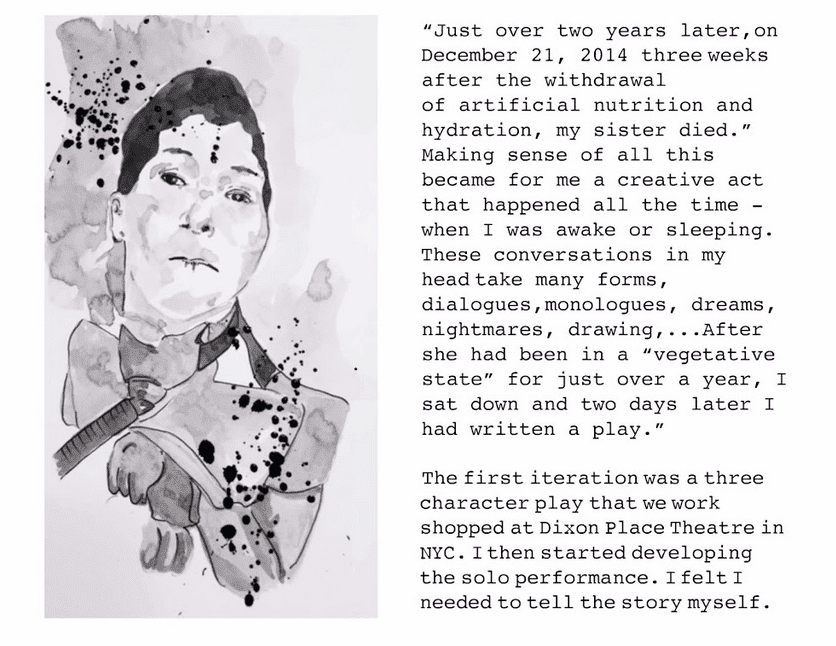

I started drawing her soon after her accident. She was a beautiful woman, a single mom of two, a daughter, a sister. I drew her for the same reason I always draw. To try and make meaning out of something I can’ t seem to reconcile any other way. So, I kept drawing and then started writing. As I watched her slowly disappear before our eyes, I was compelled to find a way to tell this story of loss, frustration, anger, grief and reckoning with all the spoken and unspoken complications of a family helplessly watching one of its branches wither and die.

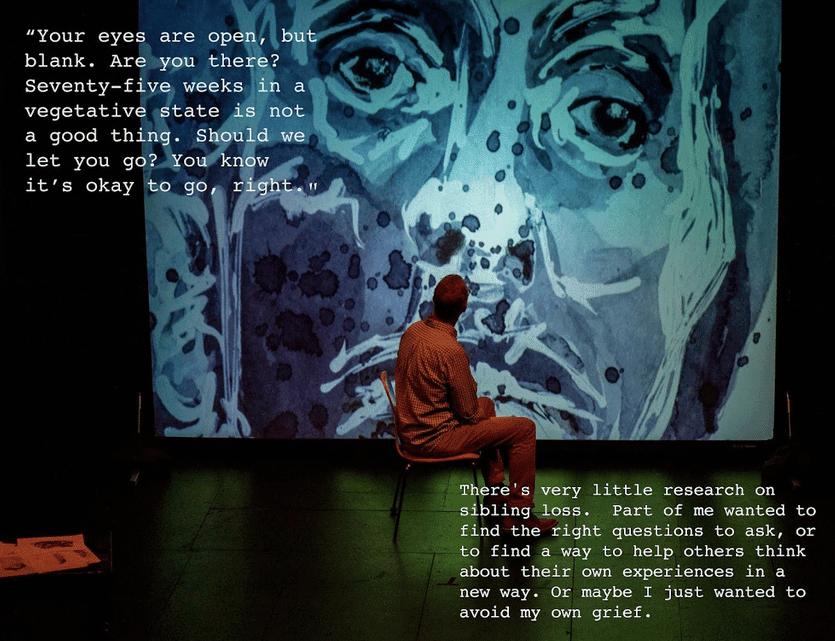

“Your eyes are open, but blank. Are you there? Seventy-five weeks in a vegetative state is not a good thing. Should we let you go? You know it’s okay to go, right?”

There’s very little research on sibling loss. Part of me wanted to find the right questions to ask, or to find a way to help others think about their own experiences in a new way. Or maybe I just wanted to avoid my own grief.

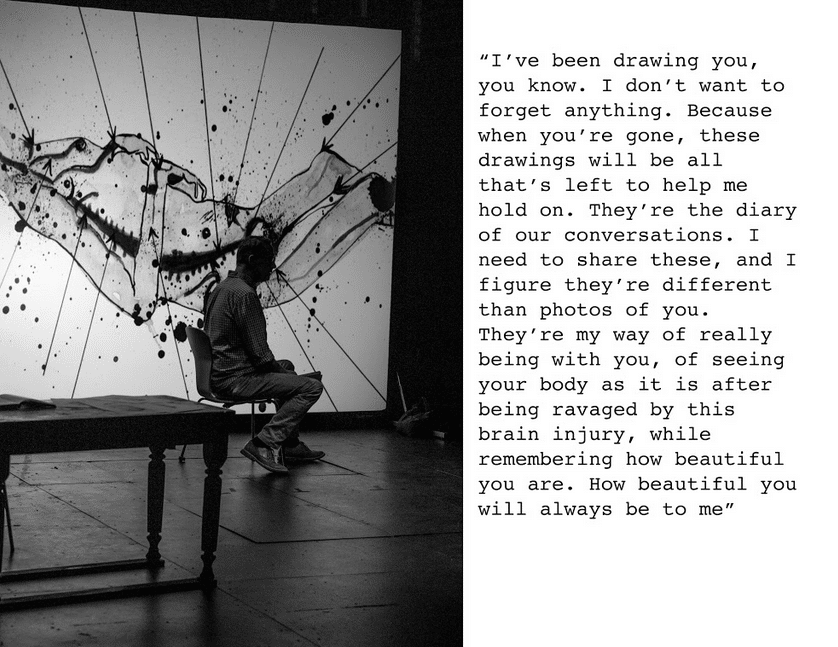

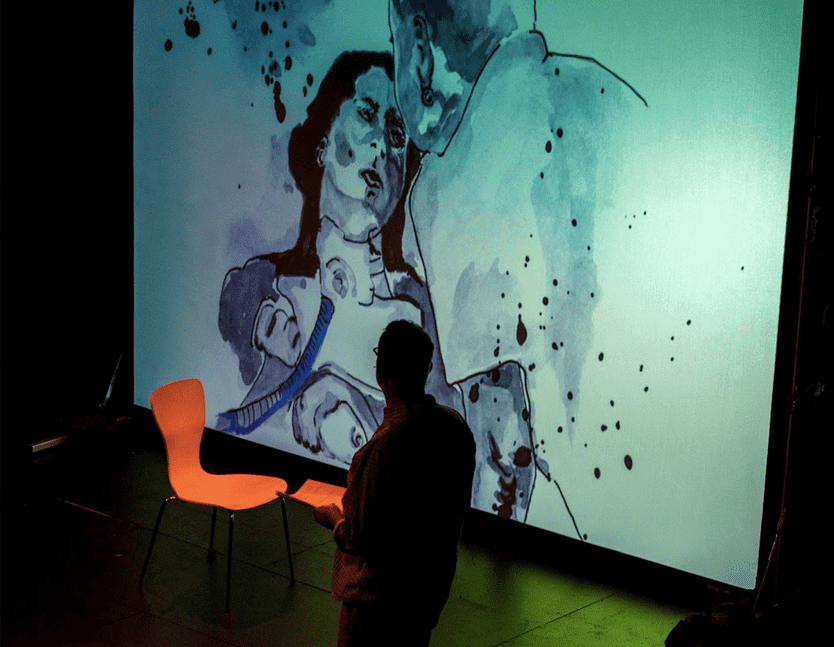

“I’ve been drawing you; you know. I don’t want to forget anything. Because when you’re gone, these drawings will be all that’s left to help me hold on. They’re the diary of our conversations. I need to share these, and I figure they’re different than photos of you. They’re my way of really being with you, of seeing your body as it is after being ravaged by this brain injury, while remembering how beautiful you are. How beautiful you will always be to me.”

I’m not exactly sure when I decided to make a performance piece about my sister’s traumatic brain injury and death. In fact, I’m not sure there ever was a single moment of decision. Her story had become public in many ways, from online care sites to prayer chains to social media posts from family and friends. Her story was being performed out in the world before I started telling it. But I worried the drawings might violate some intimacy line between siblings. I worried I might be making her vulnerable in a way she might resent. So, I confessed these things to her. In many ways, the theatre had long been my church.

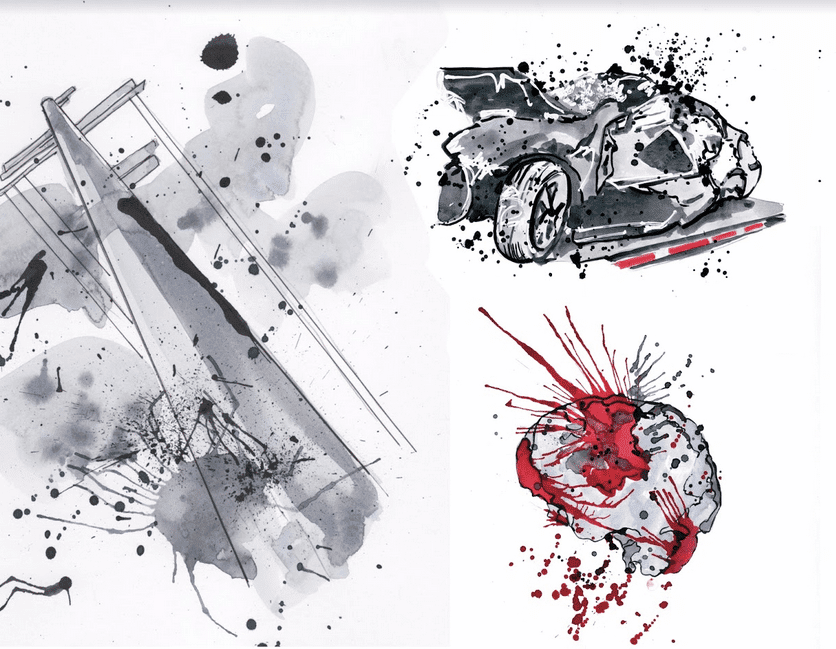

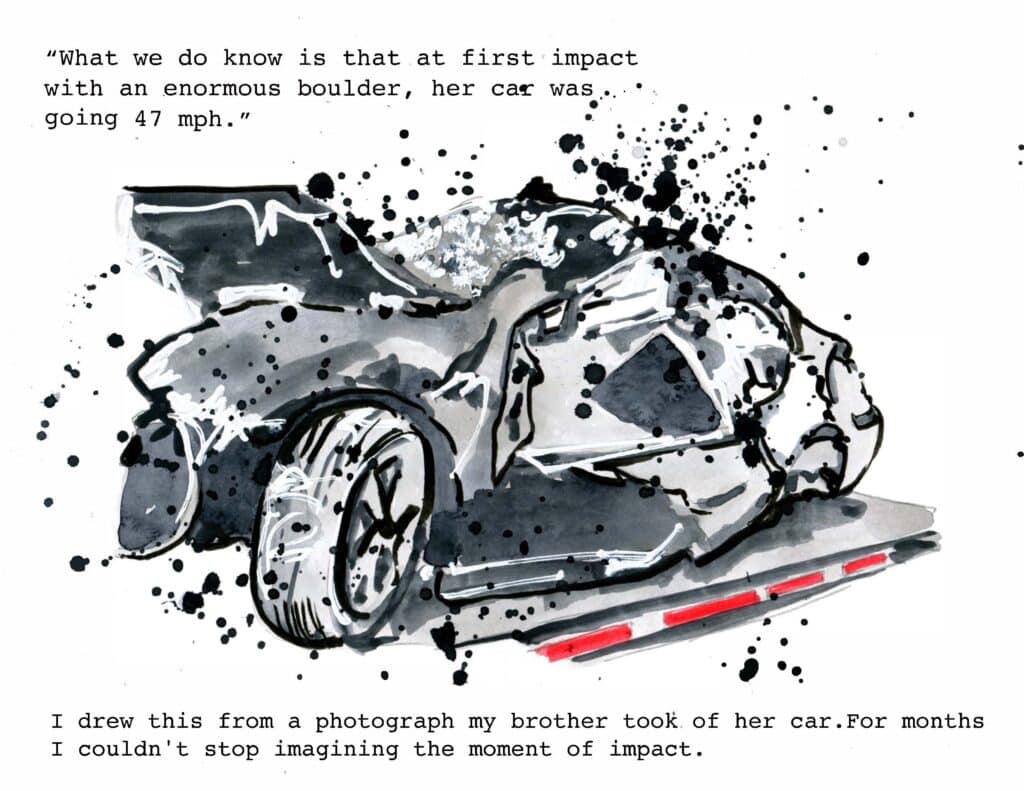

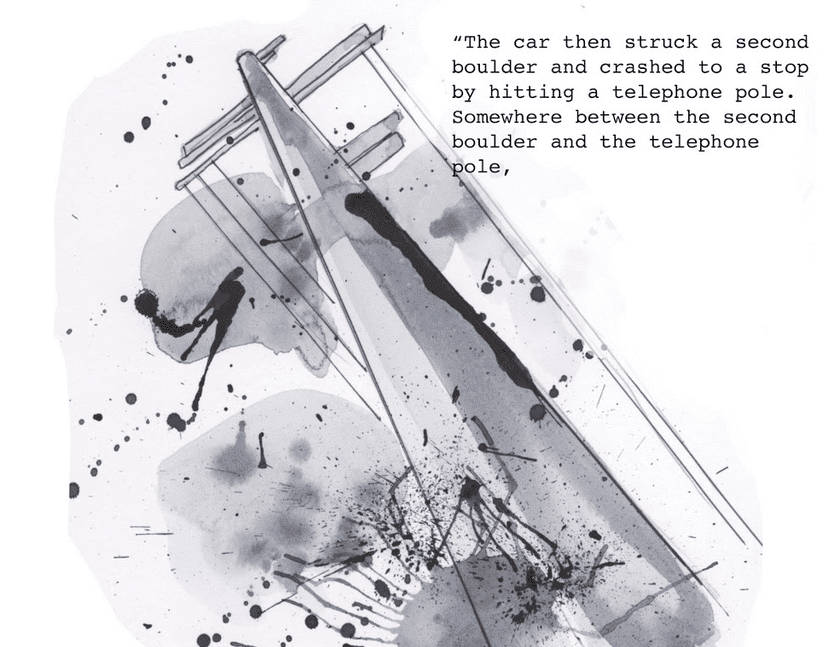

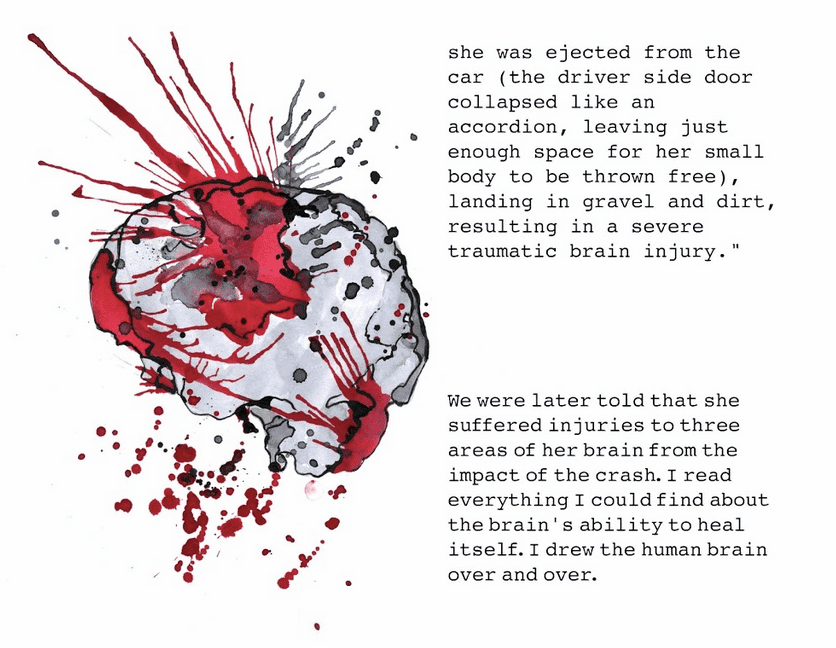

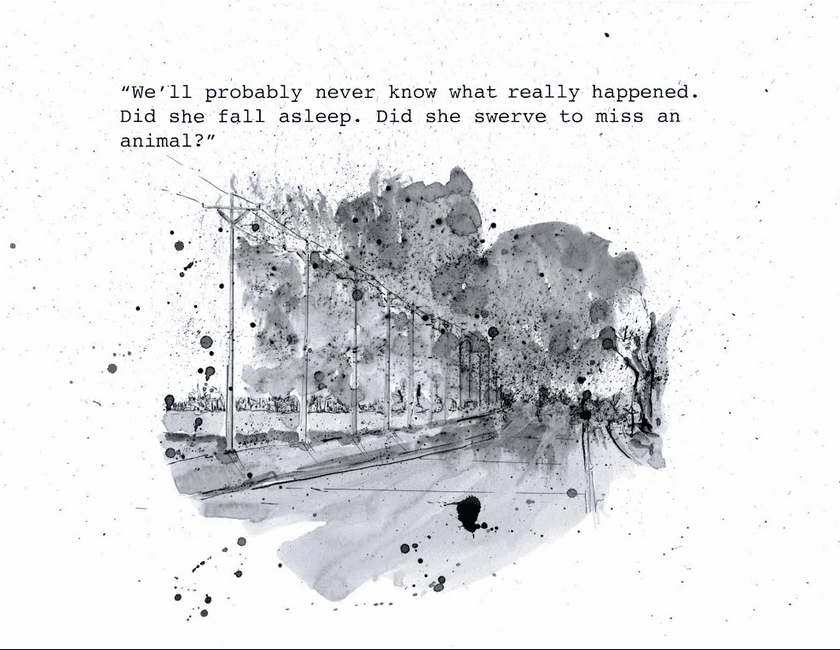

“What we do know is that at first impact with an enormous boulder, her car was going 47 miles per hour. “I drew this from a photograph my brother took of her car. For months I couldn’t stop imagining the moment of impact. “The car then struck a second boulder and crashed to a stop by hitting a telephone pole. She was ejected from the car (the driver side door collapsed like an accordion, leaving just enough space for her small body to be thrown free), landing in gravel and dirt, resulting in a severe traumatic brain injury”.

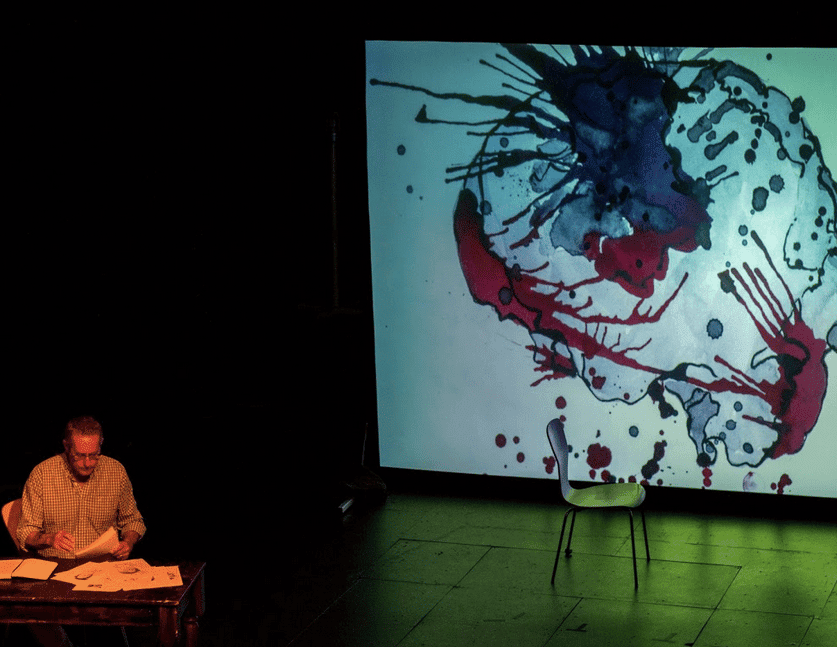

We were later told that she suffered injuries to three areas of her brain from the impact of the crash. I read everything I could find about the brain’s ability to heal itself. I drew the human brain over and over.

“We’ll probably never know what really happened. Did she fall asleep, did she swerve to miss an animal? Just over two years later, on December 21, 2014, several weeks after the withdrawal of artificial nutrition and hydration, my sister died.”

Making sense of all this became, for me, a creative act that happened all the time – when I was awake or sleeping. “These conversations in my head take many forms, dialogues, monologues, dreams, nightmares, drawing, … After she had been in a “vegetative state” for just over a year, I sat down and two days later I had written a play.” The first iteration was a three-character play that we work shopped at Dixon Place Theatre in NYC. I then started developing the solo performance. I felt I needed to tell the story myself.

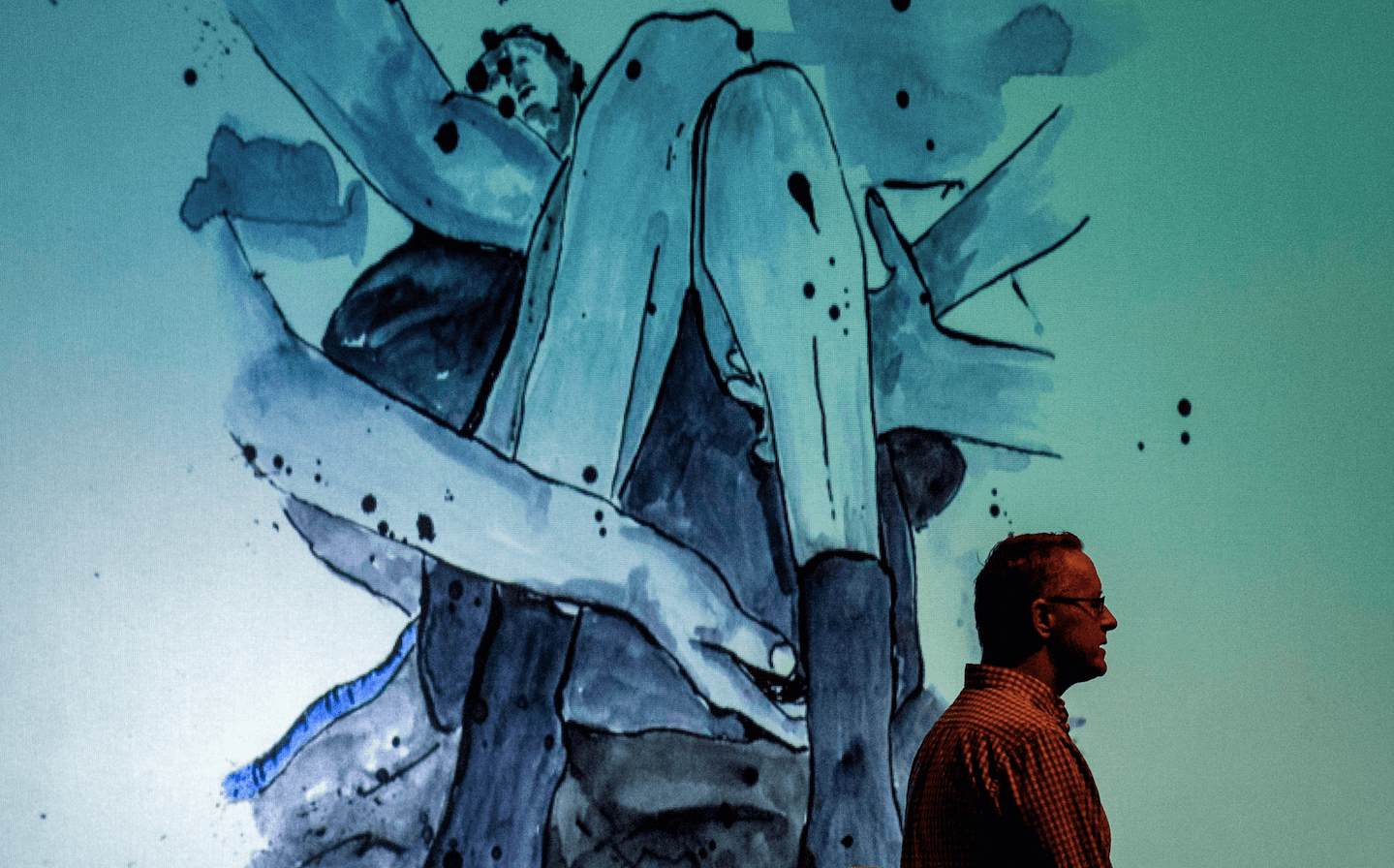

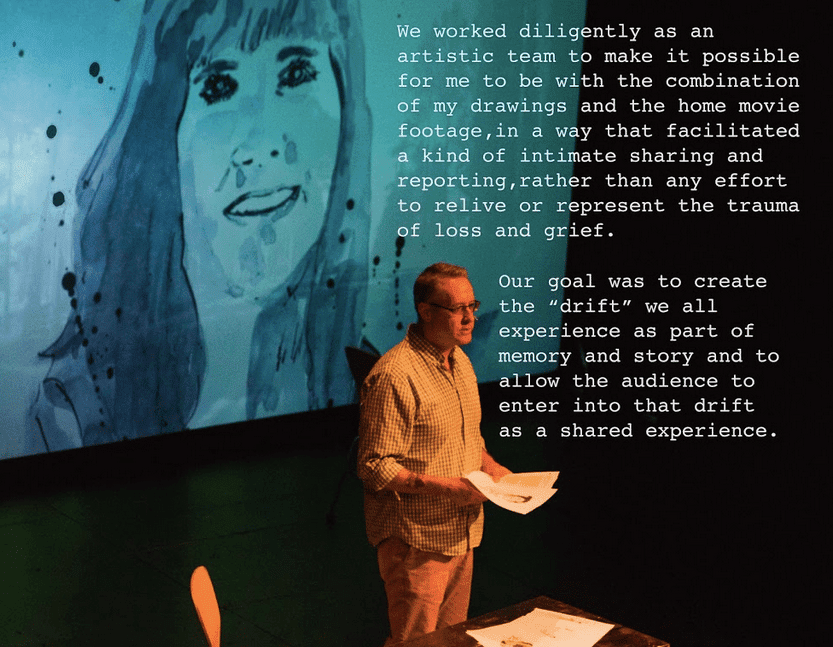

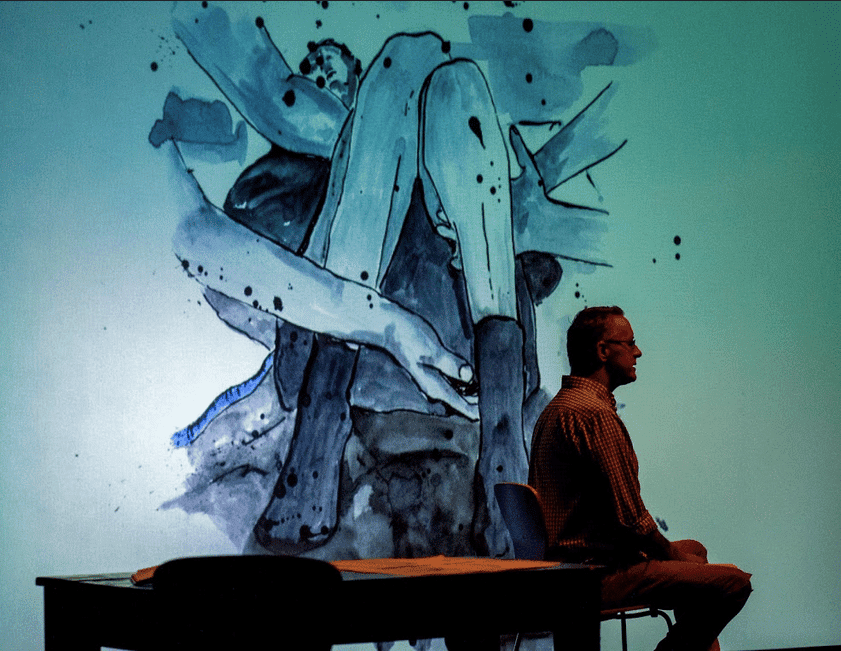

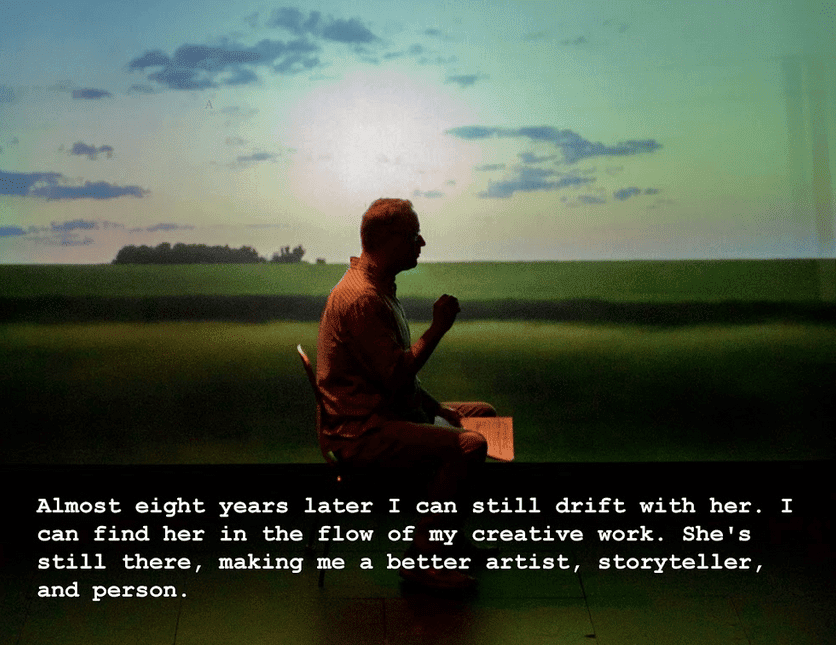

We worked diligently as an artistic team to make it possible for me to be with the combination of my drawings and home move footage, in a way that facilitated a kind of intimate sharing and reporting, rather than any effort to relive or “represent” the trauma of loss and grief. Our goal was to create the “drift” we all experience as part of memory and story and to allow the audience to enter into that drift as a shared experience.

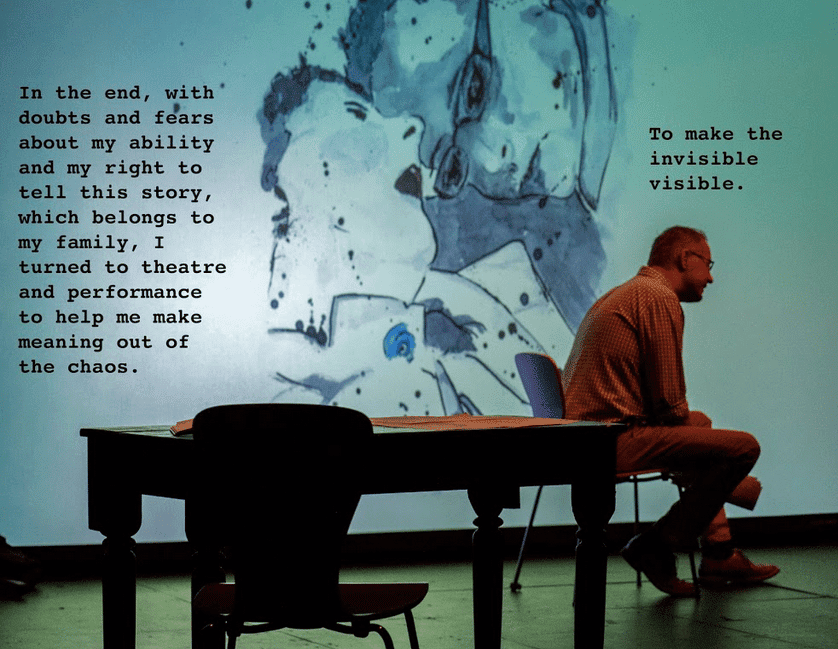

In the end, with doubts and fears about my ability and my right to tell this story, which belongs to my family, I turned to theatre and performance to help me make meaning out of the chaos. To make the invisible visible.

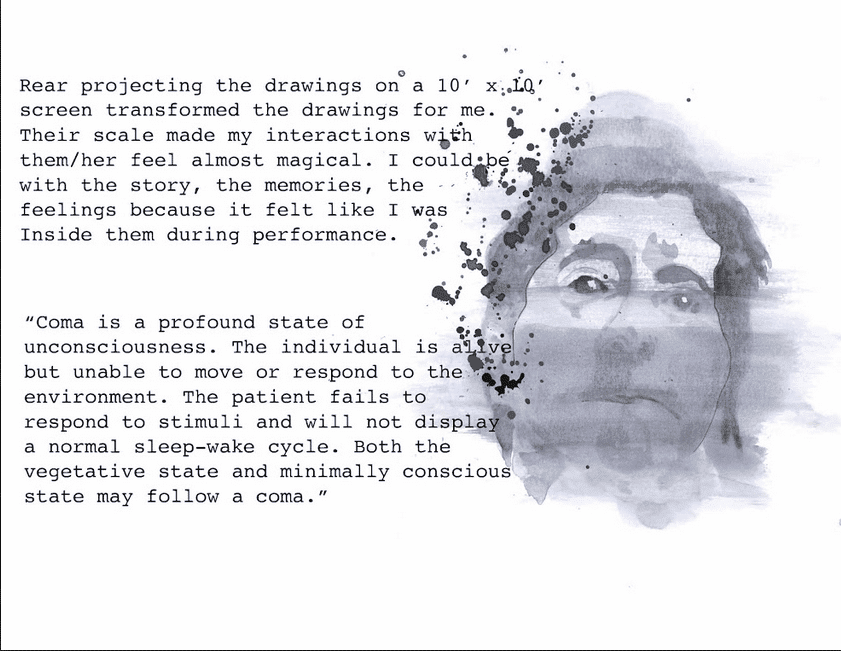

Rear projecting the drawings on a 10’ by 10’ screen transformed the drawings for me. Their scale made my interactions with them/her feel almost magical. I could be with the story, the memories, the feelings because it felt like I was inside them during performance.

“Coma is a profound state of unconsciousness. The individual is alive but unable to move or respond to the environment. The patient fails to respond to stimuli and will not display a normal sleep-wake cycle. Both the vegetative state and minimally conscious state may follow a coma.”

Almost eight years later I can still drift with her. I can find her in the flow of my creative work. She’s still there, making me a better artist, storyteller, and person.

Image of girl on tricycle with the title Drifting.

A Solo Performance about traumatic brain injury, sibling loss, memory, grief, being human.

Co-Created by William Doan and Andrew Belser.

Movement coaching Elisha Clark Halpin.

Lighting by Tyler Sperrazza.

Drawing and artwork by William Doan.

Photography by Stepanie Swindle Thomas and Avery Belser.

AUTHOR’S MEMO

Drifting began as a three-person play, part of an interdisciplinary arts-based project to investigate traumatic brain injury, consciousness, awareness, and artistic expression. Initial collaborators included a director, a movement specialist, a sound designer and sonification specialist, and a neurologist-turned-sculptor. As the project progressed, the collaborators expanded to include physicians and nurses. The project eventually became a solo performance piece as I felt more and more compelled to be the storyteller for both myself and my sister. To do this, we needed to expand the project through the creation of video projections of my drawings, as well as home movie footage. We believed the video work had the capacity to unfold the performance by visualizing the memories of the central character, who lies trapped in a vegetative state. The drawings and video are about manifesting the life that was so altered, and giving her consciousness some sort of material presence in the theatrical space. This play focuses on the spaces where art, science, and ethics intersect in complex end-of-life situations.

There was a point, not long after my sister’s death, looking at the portfolio of drawings, notes, research, and poems I made over the two-year period she was in a vegetative state, when I realized I had archived her journey to death. As an artist, I needed to make something of all that material, something that might lead me to a better understanding of how loss is an essential part of being human. I wondered if the pain and suffering my family and I experienced losing my sister could better teach me how to live. And the best way I know how to wonder about something is to take it into the studio and make something of it.