Buried Under Identities. How to Free My Sense of Self?

Author’s Memo

This article is a prequel to ongoing research into DIY Healing Within Ancestral Lands. A project born of growing up in a family system that was not kind, welcoming or loving. I did not belong. And of being purposefully isolated and cut off from another family system, that was not much better. I started this research because I needed to find a way of healing and improving my relationship with myself and others. To be the kind of parent I wanted to become. I looked around and saw that the dominant models of psychology and counselling reinforce the dominant socio-political, cultural, and economic narratives.

The focus of mainstream psychology is to get you functioning within the dominant narratives. The very same narratives that have caused the harm to begin with. As someone who has had a terrible lived experience with dominant narratives, I couldn’t see how on earth that could be a healthy or realistic path for deep healing. With a strong hunch that agency and a cohesive, flexible sense of self is essential for deep healing, I set out to cut through memoirs to unearth the places and experiences that mark us all, to figure out this mess of identity, and hopefully find a way to not need the rigidity of identity to feel strong.

‘This article is a prequel to ongoing research into DIY Healing Within Ancestral Lands. A project born of growing up in a family system that was not kind, welcoming or loving.

I planned to write about identity and the self through scenes in the film Dogma (Smith, 1999) 1. When the Metatron (Alan Rickman) tells Bethany that The Last Scion is something she can “Just, be this as well…” (Smith, 1999) 2. And when The 13th Apostle (Chris Rock) suggests that it’s better to have a good idea rather than a belief because beliefs become entrenched, hard to change. Although the film comments on faith and beliefs, the two scenes reflect what I’ve learnt about identity while researching DIY (do-it-yourself) Healing with(in) Ancestral Lands. And then came health news that derailed the plan.

Which I will come back to because this is the heart of why the research into healing ancestral trauma turned into a DIY PhD.

If I’m being completely forthright, I’ve also been procrastinating this essay. Writing is hard. Especially as someone who struggles to communicate precisely, taking in information and processing through sensations as I do. And doing autoethnography is also hard, yes. Taking a deep look into myself, critically evaluating my life experience, connecting it to broader social phenomena… It’s mind-bending and emotionally draining work. If I was just doing the research part of autoethnography, then everything I learn could stay inside. That would feel safer. No one to judge, comment, or try to fix me. It’s the sharing; sharing is the hardest part. Because I grew up in an environment where anything and everything I said or did could and would be used against me.

‘I did not belong.

Just as it was for my mother, and her mother before, and likely her mother before given that family branch’s history. A confluence of values, beliefs, norms… experiences of world war, pandemic, loss of land and homeland, and migration for safety and a better life… that family branch pounces on any perceived weakness, any difference as something to fix or look down upon. Why? To feel better about themselves. Because much of the time, deep inside, they feel pretty crappy. How could there not be an undercurrent of generally feeling crappy in such a “prove your worth as a human being” system? Nothing and no one could ever be good enough, save for the “one true guardian”. A person that embodies and thrives within the family system, holding the line. My experience of family systems and family culture is not isolated. Nor is it unpredictable.

What I’ve learned by digging through family, social, political, and cultural history is that the family Cold War has actually been a standoff in the fight for connection. We’ve been trying to connect in so many unhealthy ways. First and foremost, by having a “one true way”, to which you must adhere to be accepted and “loved”. Your identity and place within the family system is very much contingent upon how well you follow this one true way, and how well your behaviours and expression of being fit what the guardians of the one true way expect. Becoming a true guardian is the ultimate status, the ultimate acceptance, and validation that you are a worthwhile person in that branch of my family. The rest must be seen trying to emulate the guardians to be accepted.

‘I started this research because I needed to find a way of healing and improving my relationship with myself and others.

Or be willing to accept the condescension and judgment that comes with “needing help” from the guardians. And feelings were weaponized—used as proof of your problematic existence, to keep you in line, or to overwhelm you with the right of moral might. If that seems harsh, and conditional. It is. Brutal. Even if you are a guardian. And this was handed down from generation to generation to generation. To me. I grew up in a context of feelings as nuclear weapons in what appeared to be a Cold War fight for freedom. Freedom from the identities forced on me and unconsciously internalized.

This family operating system is a reflection of the social, cultural, and political environments that each generation has grown up within, and handed down. I started researching DIY (do-it-yourself) Healing within Ancestral Lands after a startling experience while researching my maternal great-grandfather’s life and context. Paul was born in a north east Pennsylvania coal mining town in the early 1900s. His father, also Paul, worked in the mines along with at least one of his brothers. The family migrated back to what was then Hungary within the Austro-Hungarian Empire somewhere around 1909. My great-grandfather’s mother died during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, and his father remarried not long after (Kopanic, 2020).

‘I looked around and saw that the dominant models of psychology and counselling reinforce the dominant socio-political, cultural, and economic narratives.

So in 1924, a 16-year old Paul left his village, farm, and family to join his older brother, who was also born in the US. He went back to that Pennsylvania coal mining town. To work in the mines. Because he could? Why, the deeper why, I’ll never know. My great-grandfather rarely talked about his family or his childhood. Definitely not to me as a toddler. And probably wouldn’t have as the daughter of a grandchild who didn’t fit within the family system if I had spent more time with him growing up.

So many relationships, connections with brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews, cousins, aunts, and uncles were lost to selective forgetting. Why? Government failures and hostilities, social pressure, religious teaching, war, family upheaval, and grief must have impacted Paul. How did he feel about himself, the world, his experiences? What impact did that have on the way he interacted with the world? And what impact did that have on the family system, and me?

Research on identity and broken families in the 18th century (Koefoed, 2021) showed that parents have every motivation to internalize expectations and emulate desired social behaviours to be accepted and belong. Makes sense. My own experience of trying to raise my son according to ideas often at odds with system beliefs about education, to go against the authoritative… well, are not fun. Isolating would be a better word. The benefits of acceptance and belonging are a core part of human existence.

‘The focus of mainstream psychology is to get you functioning within the dominant narratives. The very same narratives that have caused the harm to begin with.

To not belong jeopardizes life, livelihood, connection and well-being. From the Salem witch trials in colonial Massachusetts, to human rights and social justice movements of the 1960s and now, we see what happens to people who won’t “get with the program”. Through this research, I’ve come to see fights for identity as fights for healthy connection, unconditional love and care. Which, underneath that even, is a struggle for the right to have a self, a strong sense of self, free from an identity imposed. Let me back up a bit.

Paul’s migration experience became a source of immigrant pride and identity for his grandchildren. They are benefactors of immigrating the “right” way. If their grandfather could pull himself up, then every immigrant can. Never mind that he was born a US citizen, and that afforded Paul something his younger siblings (and most migrants) don’t have. Or that Paul’s daughter, my maternal grandmother, set about belonging by being as American as possible. The impact of his experiences, the hardships and disconnections, wore hard on the man internally. The toil and sacrifice would become chips on the shoulders of his grandchildren, the nuances of his story would be lost.

‘As someone who has had a terrible lived experience with dominant narratives, I couldn’t see how on earth that could be a healthy or realistic path for deep healing.

The fact that Paul worked his way out of the coal mines of NE Pennsylvania, to service jobs in New York City during the Great Depression, to owning a farm in Upstate New York – access to land regained! -, wove into a narrative of hardship and redemption. Clearly Paul, and his descendants by proxy, was worthy. Just look at what he’d accomplished all on his own. The individual need to make sense of lived experience to feel good, belong, actually prevented what we all crave most… healthy and loving connection. For me, I can’t see much of that in that family system. Healthy connection has certainly not been my experience within that branch of family. Researching Paul’s life, his wife Carrie’s life, has given me clues into why.

I went back to that coal mining town where Paul was born and stood in front of the church where he was baptised. I walked the cemetery, past the graves of extended family members, stood in front of the address listed on his work records from the mines and visited the town where his parents married. It was awful. I don’t mean that this cluster of towns is economically depressed. They are, but that’s not what I felt. There was something inside, at a cellular level. A revulsion, a need to get out, to vomit every trace of this place from my being. It was a truly awful weekend. I had never felt anything like that before. Being so strange, that experience stuck with me. I started paying attention to embodied responses to place and nostalgia surrounding place.

‘With a strong hunch that agency and a cohesive, flexible sense of self is essential for deep healing, I set out to cut through memoirs to unearth the places and experiences that mark us all, to figure out this mess of identity, and hopefully find a way to not need the rigidity of identity to feel strong.

Perhaps I should back up even a bit further and talk a little bit about epigenetics and trauma. I find epigenetics interesting, and insightful into the role that lived experiences play in identity. The basic premise of epigenetics is that our lived experiences can impact genetic expression, turn a gene on or off for future generations. There’s still much debate in the scientific community on when, how, for how long, and under what conditions this happens… but it happens. Overly simplified… Live through a famine (Bleker, Laura S et al., 2021) and descendants are more likely to be prone to obesity because genes for storing energy kick into overdrive to compensate.

Grow up with neglect and abuse, and that is passed on to descendants in neurology and brain chemistry (Dias, B. And Ressler, K. 2014; Maté, 2019; Maté and Maté 2022). In my case, my great-grandfather grew up in a time of chaos and grief, world war, hunger, parental loss, and who knows what else. His experiences became a badge of honour, to cope and survive. And the burden of generations after as likely culprits behind issues that visibly affect health, wellbeing, and life chances. Both in turn affecting how family members are seen by others, and themselves.

‘Writing is hard. Especially as someone who struggles to communicate precisely, taking in information and processing through sensations as I do. And doing autoethnography is also hard, yes.

As I look at the generations that came after, I see Paul’s traumas manifested physically, neurologically and socially across generations in that family branch. Traumas born of socio-political-cultural systems values, beliefs, and policies expressed individually as problems to be treated and corrected (van der Kolk, 2015; Maté, 2019; Maté and Maté 2022). ADHD, autism, alcoholism, struggles with weight, heart conditions, loneliness, isolation, diabetes, depression… this family branch has them all in spades and across generations. Personal struggles with any and all of these become markers of who a person is and where they are located in the family system.

Paul’s life experiences became a baseline for what is “normal”, what to expect out of family and life. His feelings about those experiences, how Paul processed (or not!) trauma, became a codex of not only how to be, but who holds moral authority and therefore is worthy of “love” [1] within the family. Family dynamics and structure mirror historical messaging from social institutions in Eastern Europe and the US in a self-reinforcing system. A system that is powered by memoirs[2] and strategic forgetting in ongoing power struggles for control over family narratives.

‘Taking a deep look into myself, critically evaluating my life experience, connecting it to broader social phenomena… It’s mind-bending and emotionally draining work.

These narratives are means of control, and sources of identity. The very roots of our beliefs as a family… you too, can make it by working hard, persisting, and forgetting the traumas. Put them away, stuff them deep down inside, and don’t talk about them. It’s too painful, and it’s admitting that perhaps the narratives aren’t the whole story. The hardships that Paul went through as a young boy in a war-torn, pandemic and hunger stricken, politically chaotic turn of the 20th century Europe almost certainly impacted his relationships. How could Paul hold an open heart full of compassion and love for his daughter if he did not have that for himself.

‘There was something inside, at a cellular level. A revulsion, a need to get out, to vomit every trace of this place from my being.

Was he shown love and compassion, unconditionally in early life? Certainly not by prevailing social sensibilities, government policies, or companies that owned the mines. Which, given what we know about the need to belong, means that Paul’s family system replicated and reinforced the sensibilities and priorities of social, political and economic systems around him. I can’t say for Paul, but for his daughter Anna, my maternal grandmother was overwhelmed and on a hair trigger most of her life. That doesn’t come from nowhere. Nor was it necessarily an active choice of how to be.

As a young girl, I found it really hard to be around her. It was so confusing, I wanted to throw up, get away from her. But I loved my grandmother. As an adult, I learned to understand that she was stuck on high alert, ready to explode and aggressively fend off any sign of weakness. Anna’s nervous system was in overdrive. Because she didn’t get the necessary unconditional love and care within the interactions with her parents. Especially with Paul. She never had psychological, emotional or physical safety.

‘If I was just doing the research part of autoethnography, then everything I learn could stay inside. That would feel safer. No one to judge, comment, or try to fix me.

There were no examples of how that works or feels for Anna to follow. Her nervous system was continually overloaded without a calm baseline to return to. And she was fighting against social identities of being poor and a child of immigrants. My grandmother told me on several occasions that she refused to learn her parents’ language because she was American. For Paul, Anna was a disappointment in many ways, even though she tried to live up to expectations in school and beyond. She failed to fit within the narrative Paul had of his identity and Anna’s role in that identity. Never more so than when she turned 18.

So here we have a young girl, desperate to feel and be loved, be cared for. What do you think comes next? Anna married young, not finishing high school to get out, to get away from her parents. She jumped into a marriage at 18 with a charming, handsome man who was as controlling, if less overtly, as her father. Anna even lied about her age on the marriage certificate to get out. Don’t get me wrong, I loved my grandfather. He was wonderful to me. Patient, smart, funny, gentle… Lloyd was my safe space. I was not married to him, however.

And our relationship as grandparent-grandchild meant a certain level of hierarchy was built-in. I wasn’t about to challenge my grandfather in the way that my grandmother did. Apparently, their fights were blowouts. Growing up, I heard stories of marble ashtrays being thrown at heads, forks being stuck in hands, beatings of the children for discipline, emotional and financial control. Anna’s lived experience of family replicated into the one that she created with Lloyd. Not that Lloyd’s lived experience with a family was any less traumatic.

‘It’s the sharing; sharing is the hardest part.

How could my mother have come from this environment with any sense of what it means to be with people, supportive, and together? How could she possibly know what love and care was? She didn’t, and still doesn’t today. To escape the abuse, my mother chose to escape in her head. She learned to lie to avoid wrath. To get a straight answer out of her is still is near miracle. My mother froze in response to cope with the overwhelming terror she must have felt growing up. And she dove into fantasies and stories to escape not only her surroundings, but her own lack of sense of self. My grandmother was overbearing and pushed my mother in ways that belittled and denied her a chance to grow into a person. Just as has happened to my grandmother, and her father before I suspect.

My mother’s coping mechanisms marked her within the family as the untrustworthy one. Not serious nor to be taken seriously. Fun, if lazy and a liar. Throughout my childhood, and to this day, my mother grasps at alternative narratives to cobble together an identity that is not demeaning and dismissive of her experience, needs, or of her as a person. She suffers from depression and anxiety, like my grandparents before her, and physical ailments that really mark the emotional abuse and neglect of family dynamics. Family dynamics reinforced by prevailing social sensibilities and the economic realities of being female and a single parent.

‘Family dynamics reinforced by prevailing social sensibilities and the economic realities of being female and a single parent.

My mother too married early to get out, also to a man who was another variety of controlling and emotionally abusive. Her siblings have had their own struggles, expressed in different ways. Taking on identities depending upon whether or not they fit into the family system. And whether or not they fit into the family system was largely dependant on birth order, older kids saw more abuse than younger ones, and willingness/ability to buy into the family system. Most of her generation are still without a coherent sense of self, living out identities within a family system that is maintained out of fear. Transgressors will be judged, their worthiness always in question.

For myself, well… as my mother’s daughter, my choices were to get with the program, take on the identities handed to me, be a scapegoat, an outsider, not be taken seriously because I didn’t think act or believe the “right” way, or… get the hell out. There is no in between. No acceptance of another way of being. Rigidity and a myopic insistence on a one true way of being meant that I had to choose to save myself, my self, to have an intentional self.

Having been abandoned in the way that my mother was abandoned, the way my grandmother was abandoned, the way my great grandfather was abandoned… living within a family system of people who didn’t know how to deeply and lovingly connect to and be with themselves and others… of course I’ve struggled with well, so much. Getting out and saving myself meant that I abandoned not only the system, but the people as well. For that, for all of us, I am truly and deeply sad.

‘Taking on identities depending upon whether or not they fit into the family system. And whether or not they fit into the family system was largely dependant on birth order, older kids saw more abuse than younger ones, and willingness/ability to buy into the family system.

Amalgamating a sense of self through experiences beyond that family, piecing together information gathered from observing others’ cultures, socioeconomic status, way of thinking and being. Reading articles and books on trauma and healing. Researching my family tree, places and historical sensibilities and life-worlds. While it is “very hard to keep momentum if it’s you that you are following” (Evita, 1996) I’ve been doing the work, and have gotten to a better, healthier place. Perhaps even healed enough. Enough to have the relationships I crave. And then… I’m knocked back by health news. And find myself wondering, what is healed enough?

Which brings us back to the health news.

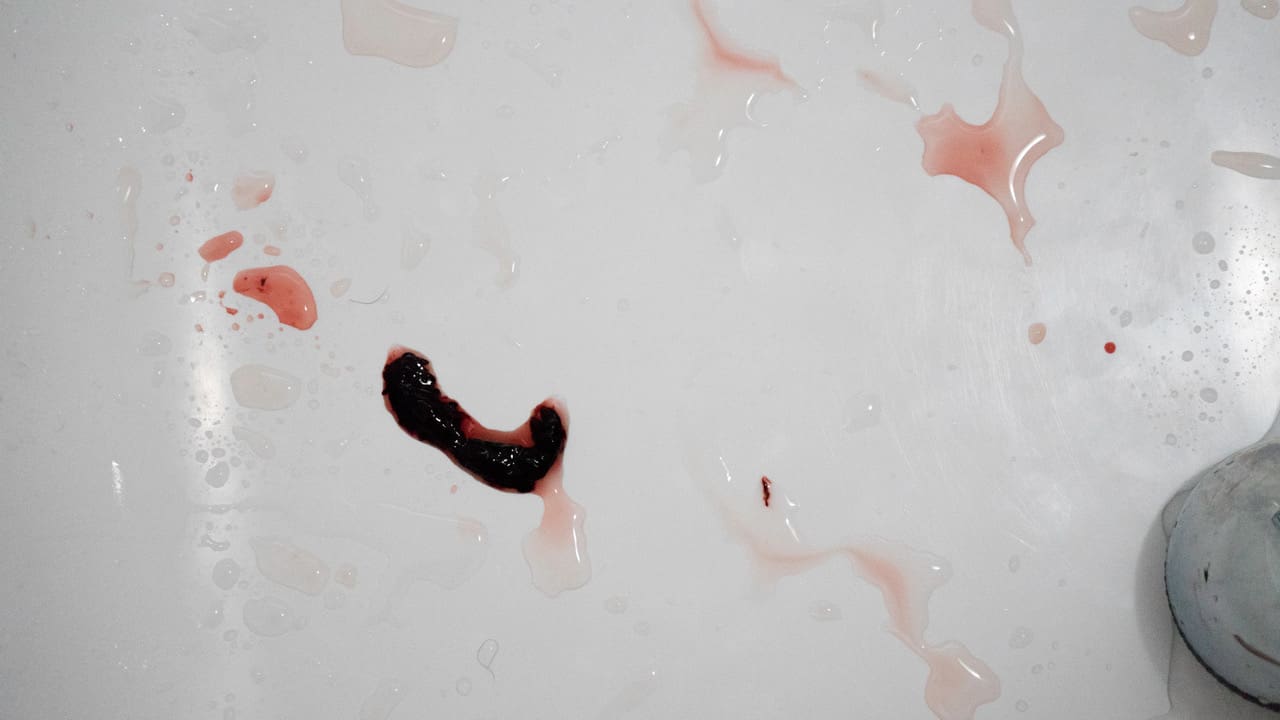

I’ve lived the last 10+ years overwhelmed. Lone parenting with little to no support or backup. As someone who processes slowly and deeply, and needs lots of down time to recharge, this was already an enormous challenge. Add to that incredible abdominal pain, fluid retention, massive weight gain, mood swings, anxiety, depression, and the inability to focus… well, how do I even begin? Just the physical side is enough. Menstrual cycles unpredictable, and so heavy that I go through a super max tampon and a super plus pad every hour. Needing to be within 20 steps of a toilet every 45 minutes, struggle getting up because it feels like tissues and muscles are ripping apart internally every time I engage my core to do something simple, like sit up, worse yet sneeze, or cough.

‘Amalgamating a sense of self through experiences beyond that family, piecing together information gathered from observing others’ cultures, socioeconomic status, way of thinking and being.

To be so tired from the incredible loss of blood every month, to have an instructor who tells me off for leaving a class several times without asking why, to bleeding through clothes and having to wash them out in a basin and be wet for the rest of the day… that is already so much. Imagine the mental and emotional fallout from living that day in and day out for 10 years. No doctor would take me seriously, I had to fight to not be dismissed, and I was told things like eat less, move more, time for hormone replacement therapy after cursory exams.

When I received the diagnosis of endometriosis, adenomyosis, anaemia and a complex ovarian cyst, I felt vindication and despair. Vindication for the proof, there was something truly wrong. And despair because it’s likely that I’ll need surgery to remove the endometrial tissue and lesions, possibly a full hysterectomy given that the tissue is growing within the muscle walls of my uterus and the cyst is a large, solid mass. Which brings us back to the abandonment.

‘I’ve lived the last 10+ years overwhelmed. Lone parenting with little to no support or backup. As someone who processes slowly and deeply, and needs lots of down time to recharge, this was already an enormous challenge.

The reason I have these medical issues is because there was no one there to care for me week three onward after giving birth to my son. I had to go back to work after five weeks because I didn’t have financial support, let alone logistical support to rest and recover from a cesarean section. Insult injury after the whole birth experience. I went into labor at work and was alone for a large chunk of it because I live within in socio-political, cultural, and economic systems that make it damn hard to build a healthy sense of self and be together compassionately. Policies lacking compassion drove me back to work five weeks after a c-section. Because as a new employee, I was not entitled to paid maternity leave.

Nor was I allowed to work from home. For a school district whose purpose is to grow healthy children. That was not lost on me.

Getting out, letting go of relationships that had been repeats of family patterns, I orphaned myself. Which left me deeply vulnerable in a time of great need. After renting out my son’s bedroom and selling off anything of value, I was out of options. So back to work I went. My immediate team was gracious and understanding. I was a hormonal, financial, physical mess. And it didn’t have to be so. It still doesn’t have to be so. It wasn’t always so, and definitely not everywhere (Wengrow and Graeber, 2021).

‘The basic premise of epigenetics is that our lived experiences can impact genetic expression, turn a gene on or off for future generations.

This news catches me in that hard transition of making a healthier self and establishing healthier connections with intention. It’s slow going. I have met some wonderful people throughout my life. People who have shown me what life could be like, how families could be. And I have met families who “adopted” me, but they weren’t my family. There are limits, a threshold for what you can ask of people who aren’t blood relatives. So far, this research has taught me much about my family’s history, how world events have affected them, and how that has impact on my life. The next step is to work with the soil that I’ve been collecting because I have not only had strong reactions to that NE Pennsylvania coal mining town, there have been other places that later turned out to be significant in my family history.

Chicago, NYC, San Francisco, the River Tay, Glasgow, London… The reactions and embodied responses to the places have been so significant that I’ve learned to pay attention. If I feel I’ve been there before, one of my ancestors probably has been. This process itself has also been healing. Being self-driven, the agency to discover and guide my own healing based on what I’m learning is helping me fill in what was selectively forgotten and reincorporate it into my being on my terms. To try new things simultaneously reserving judgment and critically examining the idea from multiple angles is freeing. There is definitely something to inheriting the lived experiences of ancestors. Be it epigenetics, cultural transmission, some combination thereof, science has yet to figure out precisely what is happening and how it works.

‘As a young girl, I found it really hard to be around her. It was so confusing, I wanted to throw up, get away from her. But I loved my grandmother.

All I can say, is that it is happening and it does work. So far, working with ancestral soil, and being in the place with descendants of those who stayed is extremely enlightening. To see how people who stayed coped and framed the trauma that drove their relatives to leave, to compare the narratives from differing perspectives… it something we all should try. The depths of how identity is thrust upon us actively, and secondarily is encouraging me to think flexibly about my place in the world. And giving me a foundational core to actively choose how I want to be, rather than internalize the assumptions and narratives that others have for me.

I’ll leave you with this last little bit to chew on… that’s probably the most crucial part of this process. Not only am I choosing for myself how to heal, I am choosing who is helping me along the way. While the title of the creative autoethnography research is do-it-yourself healing, it’s really not all by myself. The difference between modern psychotherapy and this process is learning to tune into myself and not look to somebody else for answers, a structure or a program to follow.

I am choosing the people who, at a particular moment, can and will help. Letting them know how I can be helped. They have suggestions and expertise to guide me, but I am allowing what I need, really need, to direct the process. It’s a huge break from authority based healing, one that is turning out to be far more valuable in reclaiming my self.

References and Reading

Barclay, Katie, and Nina Javette Koefoed. “Family, Memory, and Identity: An Introduction.” Journal of Family History, vol. 46, no. 1, Oct. 2020, pp. 3–12, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363199020967297.

Bretherton, Inge. “Attachment Theory: Retrospect and Prospect.” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, vol. 50, no. 1/2, 1985, pp. 3–35, https://doi.org/10.2307/3333824.

Bleker, Laura S et al. “Cohort profile: the Dutch famine birth cohort (DFBC)- a prospective birth cohort study in the Netherlands.” BMJ open vol. 11:3 e042078, 4 Mar. 2021, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042078

Dias, B., Ressler, K. “Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations.” Nat Neurosci 17, 89–96, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3594

Evita. Directed by Alan Parker, 1996.

Jensen, Stine Grønbæk. “The Rebuilding of Fragmented Memories, Broken Families and Rootless Selves among Danish Care Leavers.” Journal of Family History, vol. 46, no. 1, Oct. 2020, pp. 77–91, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363199020967582. Accessed 28 Dec. 2021.

Koefoed, Nina Javette. “Negotiating Memory and Restoring Identity in Broken Families in Eighteenth-Century Denmark.” Journal of Family History, vol. 46, no. 1, Oct. 2020, pp. 30–45, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363199020967296. Accessed 5 Oct. 2021.

Kopanic, Michael. “The Spanish Influenza Pandemic in Slovakia. 1918-1919.” 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341703230_The_Spanish_Influenza_Pandemic_in_Slovakia

Maté, Gabor. When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress. Vermilion, 2019.

Maté, Gabor, and Daniel Maté. The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture. Penguin Publishing Group, 2022, pp. 15–36.

Smith, Kevin. Dogma. Directed by Kevin Smith, 1999.

van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books, 2015.

Wang, Qi. “Remembering the Self in Cultural Contexts: A Cultural Dynamic Theory of Autobiographical Memory.” Memory Studies, edited by Daniel L Schacter and Michael Welker, vol. 9, no. 3, June 2016, pp. 295–304, https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698016645238.

Wengrow, David, and David Graeber. The Dawn of Everything. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021.

[1] Power and control as love. Not actual, unconditional love and care.

[2] The selectively remembered

Credits

Featured Image and In-text image by Kara Thorndike

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition

Kara Thorndike is interested in how we choose to be, and why. She seeks wisdom in understanding the context of experiences that shape how we are. Living in participant observation, Kara’s research and art practice reflect her lived experiences. She rejects that life, work, family, and environment are separate and/or static. Raw, blunt, and gut-level, her work strives to voice experiences, realized and otherwise… and ultimately reveal multiple possibilities of how things can be. Working how life is, antidisciplinary and intertwingled, Kara has studied social systems, distinctions between private/public, and inclusion/exclusion while earning a MA in Sociology and a practice-centered MFA in Art and Humanities. Her experiences working in education, social service, design, and art have been a journey to piece together the fragments of thriving in spite of, and within the cracks of dehumanizing social systems. Currently based in Scotland, Kara explores life with her young son in tow which is sometimes a shared hobby and collaborative work; sometimes… not so much.