In my interview with award-winning author Patricia Leavy on literary research, we also discuss her evolution from academic to novelist, her genre of “social fiction,” and her latest novels series, Celestial Bodies.

Marlen Harrison: Most scholars know you from your landmark book Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice, and your many other research methods texts that offer alternative and creative approaches to research. How did you start down this path?

Patricia Leavy: I’ve always been interested in knowledge-building—what counts as knowledge, how we can create knowledge, how to express or represent research, and the new shapes that knowledge may take. I had been writing about qualitative research methods and what a colleague and I called “emergent methods” for years. So, I was immersed in the methods literature. I stumbled across articles about research projects that drew on the arts. At the time, I wasn’t familiar with the term arts-based research (or ABR), but after some more digging, I realized this was something major.

On a personal level, I’ve had a deep love for the arts since childhood. I’ve written creatively since I was very young. I even tried to write a novel when I was ten years old, but it didn’t pan out. I took dance classes, worked in theatre, and spent much of my leisure time in art galleries and museums. When I started reading about ABR it instantly made sense to me. So, I kept reading, writing, experimenting, and I guess I never stopped. I wrote Method Meets Art because at the time there was no methods text about ABR. The first edition came out in 2008 and I was writing it a few years before that. Now the book is in its third edition and there have been translations around the world. It’s amazing to see how far the field has come.

Marlen: Eventually, you went from being a qualitative sociologist and arts-based researcher, to a full-fledged novelist. Why did you turn to fiction?

Patricia: I was frustrated with the limitations inherent in traditional ways of doing and representing research. It’s hard to explore all the dimensions of human experience in a traditional journal article. Academic scholarship is also completely inaccessible to the public and has astonishingly low readership even within the academy. At the time, I was conducting research about women’s lives—relationships, body image, identity struggles. I turned to fiction and wrote my first novel, Low-Fat Love. After that I was hooked. More than a dozen novels later, and I’ve never looked back.

Marlen: What does writing literature offer you that’s different or unique?

Patricia: Freedom, creativity, imagination, truth telling. There’s no censorship with fiction. You can be honest and dive deep into the complexity of human experience. A fictional narrative can unfold much the way life does, with layers, textures, nuance. Fiction allows you to document the world as it is, and also to reimagine it. Creating a story-world for readers to enter is magical and powerful. The characters that populate a story-world serve as guides. Readers develop highly personal relationships with characters which promotes empathy, compassion, and self and social reflection. Fiction is also a uniquely immersive experience, both writing and reading it. We get swept up in story-worlds and with characters we come to care about. As a writer, that makes it a lot of fun.

Marlen: In 2010 you coined the term “social fiction” which is now widely taken up by many researchers and writers. What does the term mean to you?

Patricia: Many people now use the term, but not all cite it properly. I say that with a good dose of laughter, you’ve got to be able to laugh. That said, there is a serious side to this. I mention it because there’s so often an erasure or diminishment that can happen when people aren’t properly credited for their work. It’s dangerous, especially for some groups. Women, people of color. As a woman I’m mindful of this. So, as I’ve always said, I did not create social fiction, but I did name it and further legitimize it. Scholars across the disciplines have long turned to literary writing—Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Zora Neale Hurston, just to name a few famous examples. But there have been many, many others. Some have had a difficult time situating their work in the larger academic and publishing landscapes. I so often hear from graduate students who are desperate to do work that feeds their soul and wanting to turn to the literary arts, but they’re afraid. There are gatekeepers. Hoops to jump. So, I created the term to situate my work and house all the wonderful work that many others have done and are doing. By social fiction I simply mean fiction that is written by researchers in any field and reflects their social research concerns or expertise. I’m often asked how social fiction differs from straight-up fiction. Intent. It’s the intent driving it and the perspective underpinning it. At the end of the day, it should stand as a work of fiction that anyone can read. It should be good literary art.

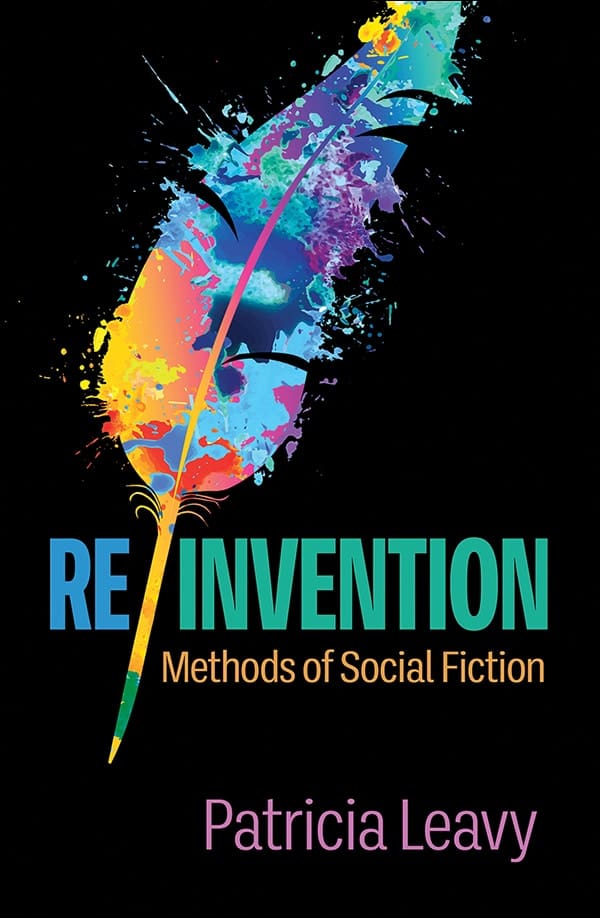

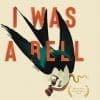

Marlen: You have two new books, both of which seem like the culmination of your work to date. The first is a huge work of fiction titled, Celestial Bodies: The Tess Lee and Jack Miller Novels. The second is a nonfiction textbook titled, Re/Invention: Methods of Social Fiction. How did it come to pass that you’re releasing two such significant works essentially at the same time?

Patricia: It’s partly a result of the time afforded to me during the pandemic. I was quarantined in my home for over a year, so I turned to creativity to get through it, writing seven days a week. Lockdown also provided more time for reflection than probably any of us would wish for. But I think it was natural during that time to take stock of one’s life, and for me, that includes my body of work. What did I most want to write? What would hold my hand during those challenging times? What would still matter to me years later? What might be useful to others? Those were some of the questions. First, I turned to fiction. I had written the first four Tess Lee novels a few months before the pandemic began. Truly, I had never loved anything more, both the writing process and the resulting books. They came from the deepest part of my soul. So, I decided to complete the series, first by revising the existing books, and then by adding two more. When I was putting the compilation together, I had the chance to collaborate with a terrific artist/scholar, Mindi Rhoades. Based on my ideas and our many chats, she created the original cover art and an illustration for each of the novels. This collection is so special to me, and I really wanted to make it beautiful and special for readers too. After writing these novels, as well as some others coming down the pike, I decided it was time to turn to nonfiction and write the book I wish had been available to me years earlier. That’s how Re/Invention was born. It was the most fun I’ve ever had writing a methods text.

Marlen: You’ve just come on as a columnist and we’re excited for you to share more about your books and ideas with our community. I know we’ve planned upcoming essay and interview pieces that will be deep dives into your books. For now, can you tell us a little about your two new releases? Let’s start with Celestial Bodies. What is it about and why is it so special to you?

Patricia: Celestial Bodies is a series of six novels that follow the epic romance of Tess and Jack: Shooting Stars, Twinkle, Constellations, Supernova, North Star, and Stardust. At the core, it’s an in-depth exploration of love—love in all its forms, textures, and complexities. Each novel focuses on love at the intersection of another topic: healing, doubt, intimacy, trust, commitment, and faith. Each novel in the series occurs a year after the previous, so ultimately you follow the characters for seven years. While each novel has a contained storyline which is brought to resolution, there is also an overarching story arc across the series titles.

Celestial Bodies: The Tess Lee and Jack Miller Novels

In terms of the characters and plot, here’s the synopsis. Tess Lee is a world-famous novelist. Her inspirational books explore people’s innermost struggles and the human need to believe that there is light at the end of the tunnel. Despite her extraordinary success, she’s been unable to find happiness in her personal life. Jack Miller is a federal agent who specializes in counterterrorism. After spending decades immersed in a violent world, a residue remains. He’s dedicated everything to his job, leaving nothing for himself. The night Tess and Jack meet, their connection is palpable. She examines the scars on his body and says, “I’ve never seen anyone whose outsides match my insides.” The two embark on a beautiful love story that asks the questions: What happens when people truly see each other? Can unconditional love change the way we see ourselves? Their friends are along for the ride: Omar, Tess’s sarcastic best friend who calls her Butterfly; Joe, Jack’s friend from the Bureau who understands the sacrifices he’s made; and Bobby and Gina, Jack’s younger friends who never fail to lighten the mood. Along the way, others join their journey: the female president of the United States, with whom Tess bakes cookies and talks politics; the Millers, Jack’s childhood family; and many others.

Really, while it’s written as a love story, it’s so much more than a romance. Celestial Bodies is about walking through our past traumas, moving from darkness to light, learning to live in color, and the ways in which love—from lovers, friends, or the art we experience—can heal us. It’s also very much about chosen families. The other relationships in the series are just as important as the primary relationship. Tess considers Jack the love of her life, but she considers her best friend and chosen family, Omar, to be her soul mate. For many, our most treasured soul is not necessarily a romantic partner, so the books disrupt the dominant pop culture narrative that romantic love is the deepest love.

As for why it’s so special to me, it’s difficult to fully explain. These characters and their stories came from the deepest part of my soul and they carry all my pain, joy, humor, and hope. The writing flowed out of me in a way it never has before and may never again. I didn’t shy away from difficult subjects, like the lifelong process of recovering from trauma, and yet, to me, there is much hope that comes through. This is a story-world filled with affection and compassion. Characters treat each other with grace. The relationships are deep and beautiful. And there’s much healing that happens on the pages. When I wrote it and when I reread it, that love and healing lives inside of me too. Celestial Bodies held my hand and embraced me in the warmest hug, and I hope the same is true for readers.

Marlen: Re/Invention: Methods of Social Fiction looks like the text a lot of students and scholars have long been hoping you’d write. From the table of contents, it appears to offer background on writing as inquiry, historical context for researchers using literary forms, detailed methodological instruction on writing social fiction, coverage of different fictional structures with published excerpts from your own work as examples, publishing guidance, evaluation criteria, and writing activities designed to help readers transform their research into fiction. Tell us about putting this book together and what you hope readers get from it.

Re/Invention: Methods of Social Fiction

Patricia: If you’re writing a qualitative research textbook, for example, you have tons of examples you can look at it to see how others did it and how you might do it differently. However, when you’re writing a textbook for which there’s no model, it’s always a little tricky. I’ve been down that road a few times. Luckily, I’ve been immersed in the literature about fiction for ages and I’ve also been fortunate to speak with many students and professors over the years, so I had a sense of what was needed. When I outlined the book, I decided there would be some background chapters to provide context and instruction. I also thought examples were important. So, there are also chapters on different fictional writing structures (e.g., three-act, open form, etc..). For those chapters, after reviewing the structure, I provide a reprinted extract from my published fiction. For each of these, I provide background about the book to situate the extract. After each extract there is an original reflection in which I talk about what I was trying to do, referring to topics taught earlier in the book, so readers can see them in action. There are also tips for those wanting to do this work. I was inspired by Carolyn Ellis’s book Revision: Autoethnographic Reflections on Life and Work. Ellis pairs her previously published writing with new reflections. I thought it worked exceptionally well in her book and that something similar could work in a book about social fiction. One of the most challenging parts of putting the book together was selecting which works of fiction to use as exemplars. For the first time in my career, I had to reread all my fiction and make some difficult choices. In the end, I tried to choose extracts that would best aid the lessons in the book, not necessarily my favorites. It was challenging because this book represents my body of work more than any other single text—my contributions to social fiction philosophy and methodological practice, and my work as a novelist.

Marlen: How do you see your relationship to autoethnography?

Patricia: The fiction I write comes through my filter. It’s imbued with my perspective, experiences, feelings. No one else could write it, which is true of everyone’s fiction. As a novelist, you’re very close to the stories you write, and yet, they are separate from you too. This can be confusing to people. For example, I’m often asked if I’m like this character or that character from one of my novels. Readers make all kinds of assumptions about protagonists they believe are based on me. The truth is, I always draw on my experiences when writing fiction, it’s unavoidable, but none of the characters are meant to be me. They do have shades of me in them, because how could they not? It’s my imagination that creates these characters and their world, so my fantasies, fears, and hopes shape them. They are a part of me. I understand them each deeply, and yet, they are separate from me and hopefully, if I’ve done a good job, they connect to others too.

Sometimes I think it’s easier to explain things through my characters so perhaps the best way to answer the question is to turn to my favorite protagonist, Tess Lee. As I mentioned earlier, she’s a world-famous novelist. Her books delve deep into pain, loss, and trauma. Readers find her inspirational, as her novels always offer a ray of light in the darkness. In the following scene from Shooting Stars, the first novel in Celestial Bodies, Tess is doing a book talk at NYU. At the end, there is a Q&A. Her response to the question posed by an audience member very much represents a piece of me that lives inside of Tess. Her reason for writing, is mine too.

After their conversation about the power of literature, the host invited questions from the audience. The Q&A went smoothly and quickly, and before long, there was only time for one final question. A woman stood up and said, “Your characters are always fighting personal battles, many related to past traumas, but your books have hopeful messages. Do you believe that healing is possible?”

“I don’t think I’m any better equipped to answer that than anyone else in this room, but I will share this from my own experience. When I was in high school, I had a boyfriend who wanted to get married. I didn’t feel that way about him and ended the relationship. He told me, ‘No one will ever be able to fill the hole in your soul.’ I still remember those words like it happened yesterday. He was hurt and he wanted to hurt me in return. For a long time, those words haunted me like a shadow. Eventually, I realized that we’re lucky if we end up with a hole in our soul. You see, our wounds don’t start out that way. They’re jagged. They have rough edges. They are like flesh that has been ripped from our body. If we learn to let love into our lives, over time, the jagged edges become smooth, and only a hole remains. Sometimes that love comes from a friend’s laughter, the hug of a child, or the embrace of a lover who sees who we really are. Sometimes giving love freely and with your whole heart can heal you too. When there aren’t people to provide that love, it can come from a song, or a movie, or even a novel. And that is why I write.”

Website: www.patricialeavy.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/WomenWhoWrite/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/patricialeavy

Note: As an Amazon affiliate, we may make money from your purchases; thank you for your support!