Emotional Research: Performing Autoethnography at My Late Father’s Village

I had not been aware that this emotional research was also performing autoethnography, collecting memories from the field together with the stories, knowledge, experience, and tangible materials which were crucial to the culture of the village. Unknowingly, the project had turned into an emotional process and a responsibility. The feelings surrounded me and it became difficult to be ‘objective’. Autoethnography, at that exact moment, came for help.

A day in a field with carpet weaver Süheyla Bayhan (on the right-hand side of me) and her neighbours. Spring, 2020. Süheyla Bayman knew my father, like almost all the villagers, and said that my father was beaten many times by his mother (my grandmother) if he ever escaped from the work in the field. She said he started to work in such a very early age that she used to give him candies secretly just to make him happy for even a second. You can imagine how these things affected me deeply.

Performing autoethnography at my late father’s village was an emotional research experience that began with the spark in my father’s eyes when I said I was planning to research the village where he had lived for 17 years before leaving to work at a well-known tobacco factory. Helvaci village (Helvacıköy), which is located in the İzmir province of western Turkey, on the south side of the Aegean Sea, took its name from an old man who used to cook halva, a kind of dessert made with semolina or flour, sugar, and milk. This man was then and has since been called helvacı or halva maker. According to the stories told by my informants during the fieldwork conducted for our project, today’s residents of Helvaci village used to live somewhere else, but they did not like where they lived because there were lots of snakes. And this old man who used to come to their village to sell halva told them that he lived in a very good place and recommended that they move there. After a while, the villagers decided to do what this old and wise man said and gradually started moving to the place which is now called Helvaciköy (Helvaci village). And later, as more people came, the village got bigger and bigger with people from different cultures, even from different countries like Somalia. So, as one can guess, there are Yörüks, Kurdish people, Gypsies and even Afro-Turks living there in peace.

Almost every summer of my childhood passed in this small village. My parents were factory workers in a then state-owned tobacco factory called TEKEL. The company was later sold to a foreign company and was no longer owned by the state. My parents were seasonal workers and worked during summers too. They used to leave me at my aunt’s (my father’s elder sister) house and visit the village in the weekends to see me or bring me new clothes. Because my aunt and her husband were (and still are) farmers, I remember waking up at 5 a.m. in the morning, getting on the back of a huge tractor and going to the fields to hoe and water the soil. We sometimes picked up the season’s crop. I witnessed the grape harvest thousands of times. I saw horses, snakes, poisonous turtles, scorpions and insects in these fields. I will never forget the calm, warm and cool breeze of these days.

As a child, all these memories about the village were quite interesting for me and I looked forward to waking up in the morning again, having breakfast with homemade bread and pekmez or grape molasses and going to the fields to have fun. But some things were missing. After all these years I now understand what was missing: my parents. I always thought about them. What were they doing without me? Did they not miss me at all all these summers?

After my childhood years, I lost my grandmother (my father’s mom) in 2008 and it was a shocking experience for me. I watched as my grandmother’s body, in keeping with tradition, was washed in the backyard of my aunt’s house. It was forbidden for children to witness the process but as an always naughty girl, I peeked through the door hole. And another shocking instance for me was to see my father cry. He was crying and crying and crying. How could my father cry? Was not he always the strongest, the most furious and most caring dad? How could that happen? I remember that I could not understand for a long while why he was crying. When we went to the graveyard of the Helvaci village to bury my grandma, how could I know that we would come to this gloomy but absurdly beautiful place with lots of cypress trees and squirrels once again, eleven years later, this time for my father.

Many years passed. I graduated from high school. I graduated from the university. Nothing happened during these years. We regularly visited the village, ate delicious meals such as pekmez and homemade nohut ekmeği or bread made from chickpea flour. Nothing happened until 2019 when as a master’s student I started to look at the village differently. In 2019, I was doing my MA in one of the best departments of folkloristics in Turkey, Hacettepe University, and began to see my father’ village as a chest of germs where I can find many precious cultural objects. As a folklore student, I realized that the carpet woven by the elderly, the meals and desserts made by the old, the traditions were unique. They had not been discovered or written. It was now a ‘field’ for me. I started to ask questions: How do people get married in Helvaci? Why do they make this bread with chickpea flour? Why do they cook keşkek (a dish of mutton or chicken and coarsely ground wheat) for three days when a boy is circumcised, or a couple gets married? My ‘why’ questions and the eager answers both from my relatives and the villagers started to get bigger and bigger. So, I said to myself: What about doing a project where I can do fieldwork, compile data and create a series of books about the village? The villagers, especially my family, would be very happy and proud. I would be too.

In an afternoon by the sea at our summerhouse, I told my intention about this ‘project’ to my father and my mother. Very emotional at that time because of his many health problems, my father burst into tears saying that he had always wanted to go to high school and university, but his family preferred to support his brother not him because of the very limited income of the family. My father said he was very proud of me. He said he was sure that I could do such work very successfully. He said that he had left the village for army, unwillingly and unhappy, at the age of 17, by applying to the court to make his age 18 to be able to join the army just to leave the home where he always felt left out, where he was always made to work, where he was always broke.

Performing autoethnography was emotionally crushing at the beginning, and I asked myself many times why the heck I was doing this to myself. I even could not conduct some interviews because there was a lot of ‘my dad’ in these conversations. I burst into tears in many of them as well. Then, I started writing my feelings, my pain and everything passing through my broken heart. I was surrounded by ‘my dad’ but autoethnography taught me that it was also legitimate and okay to express these.

While these ideas are on my mind and feelings in my heart, I applied to the Aliağa Municipality for a project to which Helvacı Village is connected. By the time we signed a contract and my father could see that I had started the fieldwork, I lost him. On the 17th of September, 2019, my mother called and told me they were going urgently to the hospital because my father had a cerebral hemorrhage, I was working on an article which I then hated and never wanted to publish. She told me as soon as possible to come to İzmir because my father’s condition was quite serious. We spent three horrible days at the hospital, in front of the intensive care unit. I was the only person the doctor talked to in the very end. My twenty-two year old sister and my fourteen year old brother went inside the intensive care unit just once in these three days. I went inside many times. The doctor chose me as the informer, the collaborator of theirs. I was chosen as a person to be told the truth in the end.

I remember the doctor calling me inside, holding my arm tight, telling me that my father’s brain was dead and there was nothing to do anymore. The next thing I heard was a noun. “Ex”. I could later understand what it was. They were calling my father “ex”. My dearest father, my daddy, was only an “ex” for them!

The following minutes, days, weeks, and months were just full of denial, tears, and depression, nothing more. As I was working at a private university which was very, very insensitive and unsympathetic to a person who just lost a parent, I continued to teach English to a group of ignorant and spoiled university students. Like a machine. Doing the work, feeling the sorrow, mourning. Nothing more. I had of course forgotten about the project with the Aliağa Municipality after we buried my father in the same graveyard where I had stood eleven years prior, unaware of the gloom of the place, trying to catch squirrels there in a very childish manner. I had forgotten everything until someone called me from the municipality. It was a middle-aged, diligent, eager, and kind man, Ali Osman Karatekin, the manager of cultural affairs in the municipality. It was he who changed my mind completely and motivated me to work on the project again.

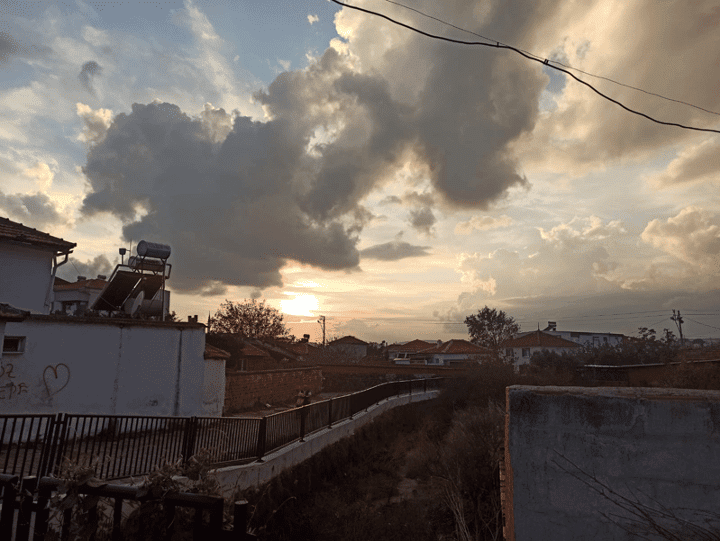

Inside Helvacı village. This was one of the gloomiest days during my fieldwork. I took the pictures of the clouds because I was feeling as if the clouds were pressing me on my head toward the ground. I was feeling heavy. It was one of the most difficult days to continue the field work.

After a couple of months, we met in his lovely office facing the Aegean Sea. I talked about all the things I wrote here. He looked very fascinated and upset as well, and agreed on starting a project to collect the tangible and intangible heritage of Helvaci Village via fieldwork, participant observation and ethnophotography. In the beginning, my main purpose was quite ‘objective’ and ‘scientific!’ By ‘beginning’ I mean the time before I lost my father. But, since losing him all the objectivity went away. I needed a method, an approach with which I could ask questions about the village without hiding my feelings, my fears, my disappointments, my anger during the process. I needed to write my memories, and those of my family, especially my father, the village and even his family.

While I was struggling to find a suitable methodology, I met the works of Carolyn Ellis, Arthur Bochner and Tony Adams. Until I read their work, been aware that I was also performing autoethnography, collecting memories from the field together with the stories, knowledge, experience, and tangible materials which were crucial to the culture of the village. Unknowingly, the project had turned into an emotional process and a responsibility. The feelings surrounded me and it became difficult to be ‘objective’. Autoethnography, at that exact moment, came for help.

Performing autoethnography was emotionally crushing at the beginning, and I asked myself many times why the heck I was doing this to myself. I even could not conduct some interviews because there was a lot of ‘my dad’ in these conversations. I burst into tears in many of them as well. Then, I started writing my feelings, my pain and everything passing through my broken heart. I was surrounded by ‘my dad’ but autoethnography taught me that it was also legitimate and okay to express these. There were very nice traditions in the village but also there were many harsh ones which in my father’s case compelled him to do more backbreaking work in the field under the burning sun because he was the younger child, seen lazier and stupid like the girls of the family. His family determined only one ‘smart’ child in the family which needed support. Other unlucky children had to either work or get married. My dad was the unlucky one and all these made him a factory worker living from hand to mouth, a long-time habitual drinker and a very, very angry person whose marriage was never good enough to make him happy.

Participating in the International Symposium on Autoethnography and Narrative on 4th and 5th January 2022 was the peak point. I understood that I was not alone. I realized that there was a huge and embracing community outside my country who emphasized that every story is unique and worth hearing/sharing.

As I said, there was a lot of ‘my dad’ in the project. For instance, the municipality assigned a driver who took me from home to the field. This man was my father’s classmate. The one and only ‘keşkek’ (a traditional dish of mutton or chicken and coarsely ground meat) maker of the village was a cancer patient at the time of my field work (2020) and shortly after passed away; he was also our distant relative and knew all about my dad’s childhood. Almost everyone knew my dad and his family. They also knew the poverty my father’s family passed through, and they did not hesitate a second to tell me all the emotional and upsetting details.

I wanted to give up thousands of times, until I was accepted to the department of folkloristics at Ankara University where I met my biggest idol, supporter, and advisor, Prof. Serpil Aygün Cengiz, who encouraged me to write about this process autoethnographically as a PhD thesis. She introduced me to the work of Ellis, Adams, and Bochner which hooked my spirit the moment I read it. Participating in the International Symposium on Autoethnography and Narrative on 4th and 5th January 2022 was the peak point. I understood that I was not alone. I realized that there was a huge and embracing community outside my country who emphasized that every story is unique and worth hearing/sharing.

As of January 20, 2022, I was halfway through the project process. I started writing the first book which I am planning to title as The Oral and Written History of Helvaci Village. Together with references from such books as archaeology and history, this book includes the stories told by informants about how the village was founded. There will be three more books on the cuisine, clothing, oral culture, and architectural heritage of the village. I need to conduct more field work for these, and of course, I am going to write my dissertation on this process from the very beginning to the end even though I don’t know how much I will suffer because constant remembering and questioning makes me tired. But after this project and my dissertation, I hope to understand more the culture of the village, my father’s life and myself. I hope this process will heal me and my family because pretending that nothing happened, nothing was felt, is not a good way at all. Confronting all the bittersweet memories about my father will free my spirit.

The Statue of the halva maker (helvacı), the old man from which the village took its name. This statue is in the entrance of the village. The man is mixing halva in a very big pot made of stone.

Map of Turkey from Google Maps. Photos by Dilek Islir Hayirli l The AutoEthnographer