In “Windows to the Self of the Performer-Autoethnographer,” I have interrogated ideas of liminality, meaning the ‘in-between’ within my practice. I am fascinated by how artists generate works that play with the boundary between public and private to explore, in relation to the question: How much do we disclose of ourselves in artwork that is autobiographical? – what parts of themselves they keep private and what parts they make public.

ARTIST’S MEMO

How much do we disclose of ourselves in artwork that is autobiographical?

Susan Broadhurst has described my artistic practice as, ‘playing with various notions of what performance is and at the same time interrogating liminality’. I have interrogated ideas of liminality, meaning the ‘in-between’ within my practice for many years. I am fascinated by how artists generate works that play with the boundary between public and private to explore, in relation to the question: How much do we disclose of ourselves in artwork that is autobiographical? – what parts of themselves they keep private and what parts they make public. In my practice, I often combine one or more art forms to explore ideas of liminality and the private and public connected to vision, visuality, and the politics of seeing and not seeing.

This article is a reflective summary of how I too have explored that question in my own practice as an artist who works across a variety of forms including collage, performance art, poetry and film. In relation to the title of this article, I will refer to how different art forms, objects and technologies I have worked with have generated different ‘windows’ for not just viewer to gain (or not) an understanding of who and what I am and my autobiography but also for me to learn more about myself by using art practice including performance art and experimental film as creative methods of autoethnography.

I will reflect upon what my experience has been like until now working with performance as autoethnography as the performer-autoethnographer…. What can I learn about myself by making artwork as autoethnography?

Throughout the article, I will map various changes in my practice in relation to the narrative content of the work and discuss how the work has shifted from me talking about the other (as in me making work about other people) to talking about the self (as in me making work that talks about me and my own subjectivity). In this latter phase of my work, practice is viewed and discussed as me performing an autoethnography; using my chosen art forms (performance, film, poetry etc.) and the chosen stories in my artworks to help me self-reflect and (better) understand myself in relation to acts of looking, seeing and being seen and the difficulty in terms of not seeing/not being seen as British, working class, male, and gay.

In the final paragraphs of the article, I will reflect upon what my experience has been like until now working with performance as autoethnography as the performer-autoethnographer and reflect upon whether it can generate possible self-revelations about my own relation to visuality, seeing etc. and how certain parts of myself I want to be seen/made public and others I want to keep hidden/not made visible etc. What can I learn about myself by making artwork as autoethnography?

SEE ME (or not) at the Slade

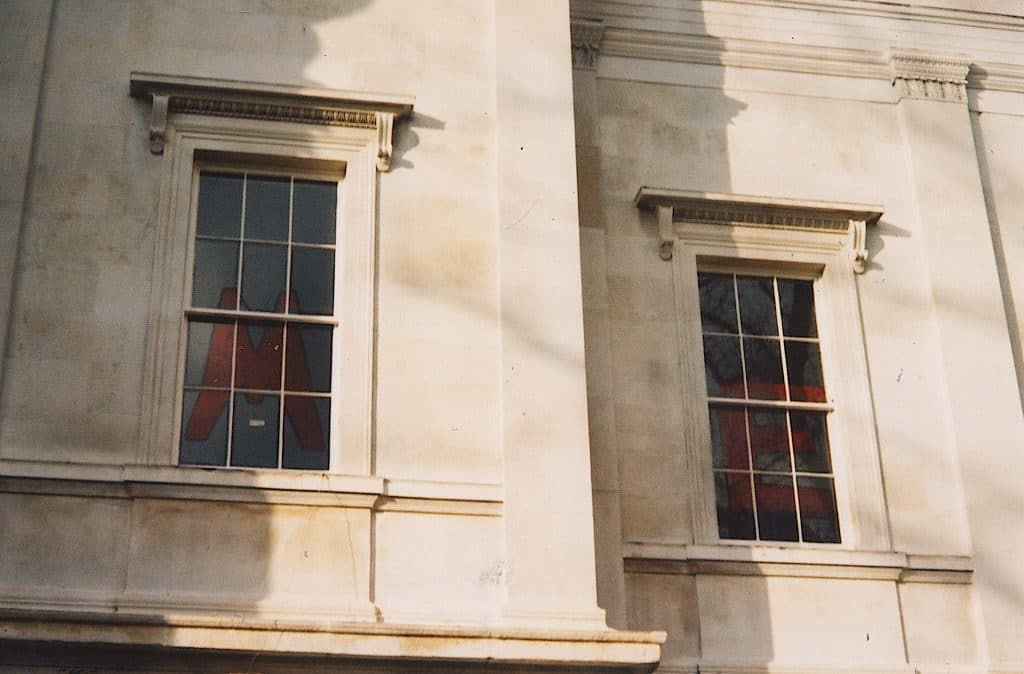

In December 2005, upon beginning postgraduate study in Painting at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, I revisited my interest in art that uses text and language by looking again at the artwork of Lawrence Weiner, Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, artists who combine text and architecture. Below are two exterior shots capturing an installation I made upon commencement of my study called SEE ME in December 2005. In relation to the title of this article, Windows to the Self, the idea of the window in this work is taken literally – referring to the windows of the Slade. The installation was part of body of practice that I was making around that time involving windows. Artwork was not just displayed in a window to be seen, the window became integral to the reading and understanding of the work, as a site to explore the self in relation ideas above referring to liminality. The window, for me, at that time represented an exciting in-between space because it is neither private nor entirely public.

‘SEE’: Detail of SEE ME, Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. Photographed by Lee Campbell, 2005.

‘ME’: Detail of SEE ME, Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. Photographed by Lee Campbell, 2005.

The words SEE ME were written directly onto the windows of the Slade with red permanent marker pen.

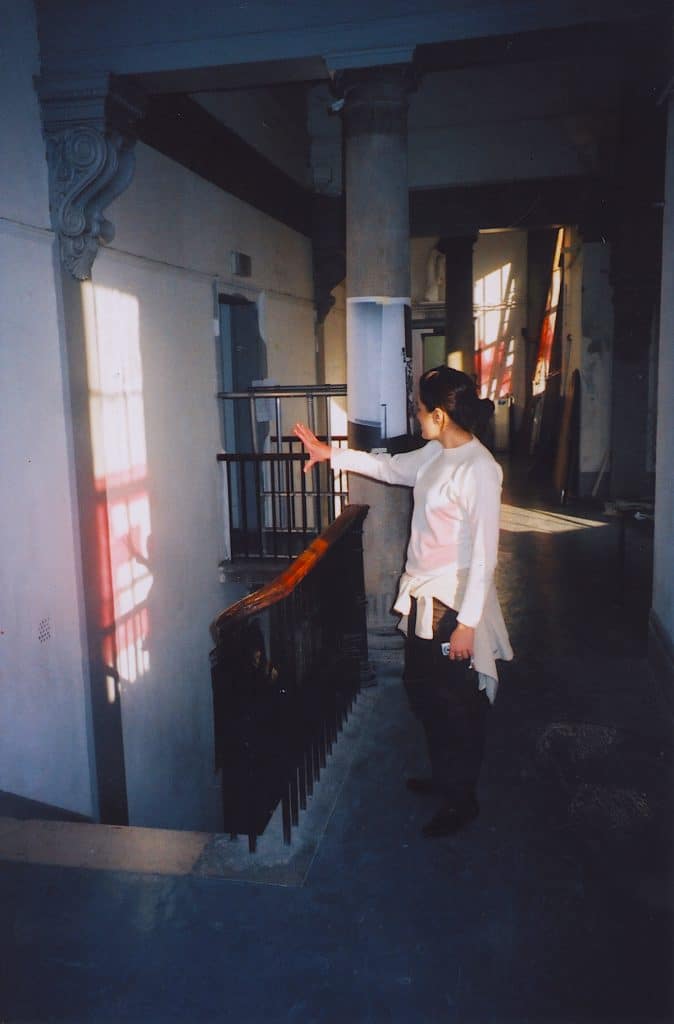

Interior detail shot of SEE ME, Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. Photographed by Lee Campbell, 2005

Interior detail shot of SEE ME, Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. Photographed by Lee Campbell, 2005

The work not only explores ideas surrounding the notion of the institution and power but also the transmission of myself as an artist exploring what forms the institution was providing for me as the time to explore my own subjectivity (working class, male, British, gay). In SEE ME I am performing my appearance at the Slade. I permanently marked my presence on its façade with all its history going back to 18th century. I am also performing the architecture in order to make myself visible, perform my own visibility. SEE ME is saying ‘see me’ i.e. me wanting to appear.

What I had not anticipated with the work would be the shadows, shadows occupying the interior of the building for brief moments in the day, weather permitting.

Shadows on the wall: Interior detail shot of SEE ME, Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. Photographed by Lee Campbell, 2005

The shadows having a fleeting impermanent presence, elicited a form of viewer interaction. I described at the time seeing passers-by i.e. my tutors and classmates playing with the shadows as them literally immersing themselves in me.

Slade student Maria Glyka playing with the shadows. Interior detail shot of SEE ME, Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. Photographed by Lee Campbell, 2005

If you arrived to see the work on a cloudy day, you would not see the work i.e., you would not see me. The work was absolutely dependent on climate change. Those bigger forces of nature and their transformations allowed me to be seen or not seen. SEE ME was so implicated with the architecture. I am performing the architecture. And architecture always performs the climate, that’s what architecture does. It’s always structuring how light enters a building; its multiple aspects how it moves across a space. How a space is allowed to come into being as a space. This work prompted my tutor, Bruce McLean to comment that he felt that I should ‘be more’ in my work and I took that comment very literally in terms of me (my physical body) appearing in the work. Upon reflection of this comment years later, I believe that Bruce actually meant that my work then should have more directly addressed issues of my identity and sexuality and specifically, I state my desire. At the time I made SEE ME, I knew I was gay but was not fully ‘out’ and whilst SEE ME is a self-portrait in relation to ideas of (in)visibility, I did not feel comfortable at the time bringing my queer subjectivity into the work so directly or solemnly. Reflecting upon my time at the Slade when I was in my late 20s, I see it as a period where I was trying to learn what the Slade as an establishment was in terms of providing for me with forms to explore my own subjectivity as well as trying to understand myself and take my subjectivity in.

Performance as Autoethnography

Acting upon Bruce’s ‘be in the work more’ comment, my practice after SEE ME took a new direction: performance for camera. After being encouraged by Bruce to explore performance art and then inspired by the moving image work of a recent retrospective of another Bruce, Bruce Nauman at Tate Liverpool in 2006/7, I began generating performative actions and recording these using my mobile phone in a similar vein to the film directors of La Nouvelle Vague; post-war French New Wave cinema, who were influenced by the concept ‘camera-stylo’ meaning using the camera like a pen. Experimenting with my mobile phone’s (the Sony Ericsson Cybershoot K800) software, I prioritised its relative ease of use in terms of its stills/ video camera. Despite the phone’s minimal amount of recording features, the small, unobtrusive, easy to operate phone enabled me, as someone at the time who considered themselves not particularly ‘tech-savvy’ or au fait with complicated editing techniques, to get to grips with working with performance and performing in front of a camera for the first time. After creating several short films using my phone, I then realised that what was really important for me was live performance and its capacity for the unexpected (in the way that the shadows were an unexpected outcome within SEE ME). Nearing completion of my studies at the Slade in 2007, I began to create solo performances where I was no longer performing in front of a camera but in front of a live audience. One of these performances, very much in the vein of how artist Bruce Nauman combines comedy slapstick, body movements and repetition, was Yes/No (2007), which I performed at Battersea Arts Centre, London – my first event live solo performance, and Bruce was in the audience watching.[1]

A drawing of ‘deadpan’ performer Lee Campbell by Bryan Parsons during Yes/No (2007)

The performance took place in a black box, a space where the walls are painted black and the floor painted white. Black box refers to the traditional bog-standard spatial arrangement for theatre where audiences sit and watch a performance in relative darkness. The black box became the window to the self as referred to above. The performance examined the relationship between what the audience hear and what they see. As I performed actions, I every effort to maintain non-emotional facial expressions, which made me appear serious and deadpan (a continual trope in slapstick) and not at all bemused by the slapstick activities that I was engaged in. I learnt a lot throughout this process, from hearing the audience roar with laughter to how I felt at the time as a performer. The audience produced laughter during Yes/No, as I appeared to them to deliberately force my body to be clumsy not just once, nor twice but many times repeatedly. Me enacting a form of physical and bodily clumsiness and then reenacting the same clumsiness repeatedly heightened the nonsensical nature of what I was doing whilst at the same time generating more and more laughter from the audience. Audiences may well have been captivated by the performance as they wanted me to fail (an example of Schadenfreude –a word in German meaning getting pleasure from seeing someone else’s failure/misery/clumsiness/pain); they wanted me to get the action wrong which would have meant me nodding when saying yes and shaking my head when saying no. The absurdity in my performance was increased further by me maintaining non-emotional facial expressions throughout the entire performance, making me appear serious and deadpan (a continual trope in slapstick) and not at all bemused by the slapstick activities that I was engaged in.

Comedy historically comes from a queer identity defence, when it was harder to be gay in public, to be funny like Kenneth Williams who used gay slang known as Polari to communicate with other gay men covertly. As a means to express as well as emotionally protect, LGBT folk historically and today embrace and use camp, daftness and a range of comedy forms in subversive and often surprising ways. This performance, in terms of its comedy daftness certainly extended these ideas – I was a gay man on stage performing something very silly but sophisticated in its relatively simple set-up. Whilst on one sense, this performance was beginning to bring ‘me’ more into the work, it was also prompted a period of work where I removed my subjectivity from within its narrative. Whilst on stage, I felt nervous, part of a continual nervousness that I had been feeling upon starting to be a performer and I was unsure how to receive the gaze i.e. I was nervous at how much of ‘me’ the audience watching me may take from the work. Although I continued to make solo performances for around five years after, none of these subsequent performances directly related to my queer subjectivity or state my desire. Spurred on by the image displayed earlier in this article of Maria playing with the shadows, the majority of artwork I made between 2007-2019 centred upon audience participation and generating artworks where the audience were both the subject and the object. In the last part of that period, between 2015-2019, I created a body of practice that involved me inviting members of the blind community to participate in audience participative artworks. Getting myself into some hot water ethically about my own subjectivity as a sighted person working with the blind community in terms of me having to deal with critics bemoaning me for trying to understand blindness as a sighted person (to which I would reply to them, ‘Where is the role of empathy?), I connected ideas of blindness and seeing/not seeing and replaced ‘the other’(i.e. me working with other people in audience participation artworks) with ‘the self’ and that of my own subjectivity. In late 2019, I now finally felt comfortable to talk about my identity and sexuality much more explicitly within the narrative of my artwork and was ready to state my desire.

Experimental Film as Autoethnography (and a return to Performance)

Promotional poster for See Me: A Walk Through London’s Gay Soho, 1994 and 2020 (2022)

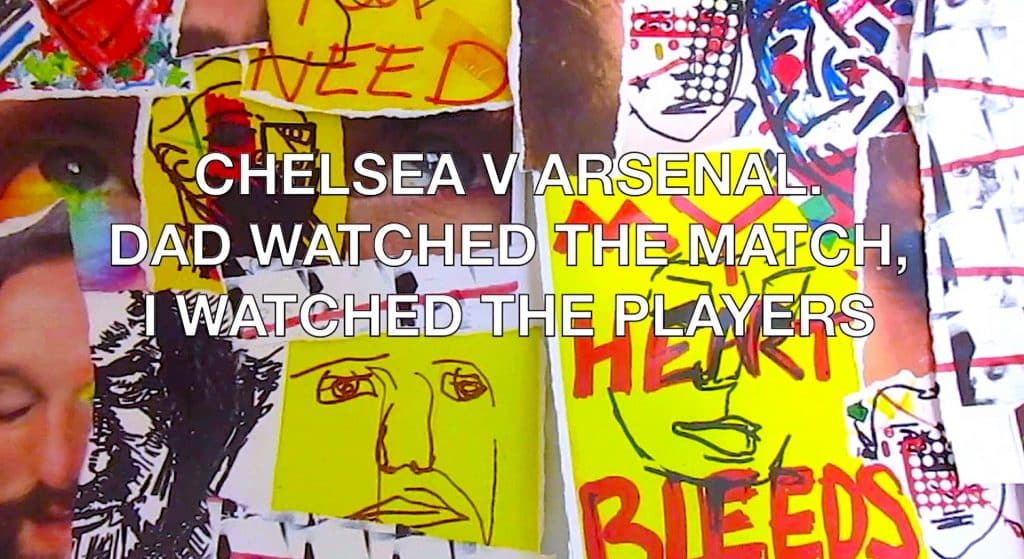

From late 2019, whilst making a series of short experimental films which I write, direct and perform in, I worked with the screen as a form of window to the self. Designed to be presented on large projection screens in cinemas (the standard presentation for works of cinema/moving image) and also in art galleries, because of Covid-19 lockdown restrictions and work being shown online, the window was then reconfigured to include a computer screen, laptop screen, mobile phone screen etc. for the viewer to watch a film. Having produced many films by the start of 2022, I have curated the films into a collection. SEE ME: (An almost) autobiography is a collection of fifteen short poetry films sharing my personal history of seeing and not seeing as a working-class gay British man, to confront the politics of seeing and underline how validating seeing can be but also the difficulty of not being seen. It presents a journey through different relationships including those as a teenager to my dad (e.g. in Let Rip: The Beautiful Game), grandparents (e.g. in See Shells), teachers, school peers, work colleagues (e.g. in Covert Operations and Head Boy) then adult relationship to gay community (SEE ME: A Walk through London’s Gay Soho …), alter ego (e.g. in Camp-Belle), my partner (e.g. in Nice Cup of Tea,Rufus) and spaces of queer imagination (e.g. in The Tale of Benny Harris, Cottage and The Perfect Crime: A Doggy Whodunnit). Whilst each film can be understood as one person’s (my) narrative so too can it easily be read as lots of different voices layered to talk about wider levels of experience with various references to cultural context that (any)one can relate to: football matches, George Michael, late night TV, bad porn, fancying schoolteachers etc (e.g. in Let Rip: Personal History …. and Clever at Seeing without being Seen). The collection also addresses a range of complex and tricky issues including body shaming and bitchiness within the gay community. self-worth, doing things to ‘fit in’. unrequited love, unobtainable love, unsatisfying relationships, fear of being left ‘on the shelf’ (e.g. in Spinach and Eggs), as well as internalised homophobia and confidence (e.g. in Camp and Reclaiming My Voice).’[2] These short films which reused and recycled bodies of my past artwork and many used the ‘rip’ as both metaphor, symbol and filmic structure to build upon existing work, create new forms out of ‘old’ practice and indeed show new versions of ‘old’ me. This meant creating surfaces and layers on the screen which I would appear to be ripping or tearing apart to reveal something about myself.

Still from the film LET RIP: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF SEEING AND NOT SEEING (2019)

The ‘rip’ in terms of this work could be defined as creating visual textures on screen which both concealed as much as they revealed and that ripping something apart did reveal certain things about my homosexuality, but I also kept a certain part of myself concealed/hidden/in private.

Still from LET RIP: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF SEEING AND NOT SEEING (2019)

Many of the films that created within the Let Rip series like LET RIP: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF SEEING AND NOT SEEING begun life having written text placards on screen rather than me speaking poetry that I had written as a voiceover. A friend when watching A PERSONAL HISTORY OF… suggested in November 2020 that the written placards within this film needed to be spoken/performed/read aloud by me rather than written as I have a particular voice from a particular point in London queer history. My friend suggested that my voice and my accent evidence my life so clearly – a specific voice that gives me a specific identity to a specific place.

And so in late November 2020, excavating text from my films to create live spoken word poetry pieces, I began writing poetry about my identity as a gay, working class British man and perform /read these aloud for the first time at regular LGBT centred open-mics that were taking place online because of lockdown restrictions. I remember my first open-mic set for PoetryLGBT. I was so nervous, legs trembling, my stomach was in gut wrench, I had performer’s butterflies in the stomach feeling for the first time in a long whilst as this was the first moment I was performing live to an audience and sharing very personal details with an audience who I could not see. The response, however, to my performance was incredible. After that first performance, I then used the films that I had made like as video backdrops when performing on Zoom which audiences absolutely loved.

Still from the Zoom performance CLEVER AT SEEING WITHOUT BEING SEEN (2021)

Still from the Zoom performance SPINACH AND EGGS (2021)

For transitstation voices #3, part of the poetry I perform talks about the scrapbook I refer to in my film LET RIP: TEENAGE SCRAPBOOK (2022). I printed out digital copies of pages of the scrapbook to use throughout the performance, the first time I had done so. I did not anticipate before the performance started exactly what I would do with them. The moment in the performance where I start to play with the pages of the scrapbook bought an exciting physicality back into the digital space – these pages that conjured up so many (difficult) memories for me. Pages of the scrapbook appearing digitally on screen as the green screen effect complexified by me engaging with the pages physically. Up to that point, much of the performance in terms of what I said and did, had been rehearsed but this moment with the pages was a breakthrough moment of off-the-cuff improvisation, serendipitous play, of exploring for the first time in front of an audience.

Still from the Zoom performance CLEVER AT SEEING WITHOUT BEING SEEN (2021)

Still from the Zoom performance CLEVER AT SEEING WITHOUT BEING SEEN (2021)

Still from the Zoom performance CLEVER AT SEEING WITHOUT BEING SEEN (2021)

I remember co-curator Charles’ comments about how this moment created a different texture within the performance. Up to that moment the audience could hear pages being ripped, they could see images being ripped as part of the green screen (or in actual fact, being smudged out and replaced). The moment in the performance where I then ripped the physical pages seemed (even more) violent but for me it felt like a real moment of emancipation/potentially finally freeing myself from these images/from the memories.[3] However, working with the images digitally, I knew that the images are not being destroyed (by ripping the materials (the paper) physically). The viewer knows that the image is being smudged/wiped out, but the image is still there because of technology (the image still exists digitally). But when it’s the paper being ripped, the image is gone. As painter Andrew Bracey commented on this aspect of the work, ‘There is an irrevocable harm. But as the image is digital I know that I can bring it back’. Whilst it felt good ripping the photocopies in a cathartic way during the performance as it felt like I was showing a sense of anger that ripped through the (in places) saccharine sentimentality of the accompanying poetry, maybe I would not have ripped the original scrapbook pages. Then again I did throw my scrapbook away and document its contents with a lo-res mobile phone camera rather than preserve it carefully. The ‘physical rip’ in the Zoom performance garnered such a positive response from the audience that I segued a section of it into the original Teenage Scrapbook poetry film to add a moment of recorded live Zoom ‘interruption’ into the flow of the film.

Final Thoughts and Reflections on the Performer-autoethnographer

Reflecting upon the question: ‘How much do we disclose of ourselves in artwork that is autobiographical?’ in relation to the ideas and example of practice presented above, I have realised there are certain parts of myself I prefer to remain private/at bay. If I reflect upon ripping as a kind of revealing, as a sense making process, what my reflections reveal about me is that maybe I can never really let go of the past and I am drawn to going back to my personal archive as a strange yet pleasurable activity as it reminds me how ‘far’ I have come in terms of not being comfortable in sharing any part of my (queer) subjectivity in my teen years.

Reflecting upon using performance as a form of autoethnography, I enjoy both producing (performing) and witnessing live performance because I do not know what I am going to get – I cannot anticipate exactly the outcome – what is going to happen. I cannot be fully in control of the situation/control the outcome unlike when I was making films which I had total control over in terms of their production/outcome. Improvisation, serendipity and the unexpected are important to me.

In live performance, I cannot foresee exactly what is going to happen in the running of events and what my emotional responses will be etc. Dwight Conquergood (2002) describes Performance as ‘a way of knowing’ (p152). I suggest that the knowledge that Conquergood suggests here is dependent upon a ‘not knowing’ at the start and throughout the duration of a performance. During a performance, often my expectations of what I foresee may happen are disrupted by actual events, for example, the audience laughing throughout Yes/No (2007). Performers on stage have a need to be seen/to be witnessed. This sets up an interesting question: ‘Is a performance a performance without a witness/without being seen?’ Accepting the serendipitous nature of working with liveness, the question is how does the performer-autoethnographer embrace Performance as radical not knowing and cope with the chaos (the disruptive potential) of liveness in terms of what they may (unexpectedly) reveal about themselves in front of an audience present and live? I suggest that it is worth the risk and that authoethnographic performance can be a potential site of revelation which may be able to begin to heal traumatic experiences. With this in mind, in my most recent practice, I have begun to investigate how duration operates within my work in terms of how different time durations of performing may prompt/force me to reveal/disclose various autobiographic details.

References

Conquergood, D. (1989). Poetics, play, process, and power: The performative turn in anthropology. Text and Performance Quarterly, 9(1), 82–88.

[1] You can view Yes/No, Battersea Arts Centre, London (2007) here:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/wrmvr7hqxhdqb1h/Yes%3ANo%20%282007%29.mov?dl=0

[2] You can view these works here: https://filmfreeway.com/LeeCampbell

[3] To view a recording of this live Zoom performance, please visit

https://filmfreeway.com/CLEVERATSEEINGWITHOUTBEINGSEEN2021597

Featured image by Lee Campbell I The AutoEthnographer