However, Emily has discovered one pitfall of working in ACL: The uncertainty of employment. It dawned on Emily that she could do both. She didn’t have to be an artist or a teacher. In fact, she needs to be an artist to be an artist-teacher. She needs to do both to become the best she can be.

AUTHOR’S MEMO

Emily* hadn’t always been an artist-teacher, but she had always taught, aged between 25 and 44; this is her story of how she became an artist-teacher in Adult Community Learning (ACL). For example, https://aclessex.com. Emily is a composite character of me and four other artist-teachers in ACL. Emily’s story had been composed by drawing on collaborative witnessing (Adams et al, 2014:87), by including multiple perspectives, including my own, to make visible details of lives lived and emotions experienced in a “reflexive connection” (Pace, 2012:5). This research is about individuals who have an “artist-teacher” identity (2012:2).

This autoethnographic vignette is “presented as a story with a narrator, characters and plot” (Pace, 2012:5) and employs the use of a third-person voice, to describe the “experiences, thoughts, feelings, and actions” of Emily (Adams et al, 2014:78). Emily becomes a rhetorical figure for the story to be told through.

Autoethnography has been chosen as “narrative is the best way to understand the human experience” (Ellis, 1993:727), as it can be used as a vehicle to give meaning to “identities, relationships, and experiences” (Adams et al, 2014:23). The intention is that the reader is immersed in the experiences of Emily, which in turn leads to an understanding of how one becomes an artist-teacher in ACL.

The vignette is in part a found story, repositioning words and phrases from my reflexive writing, personal experience (Pace, 2012:2), and interviews with other artist-teachers in ACL. The vignette is one way in which to “make sense and organize a mass [of] information” (Ellis et al, 2014:66). Writing in this way allows me to develop an understanding of my own experience with others (Ellis, 1993:727; Adams et al, 2014:46). Through the “thick description” of the culture I am embedded in and writing about, I can facilitate an understanding of the culture for a reader outside of it (Adams et al, 2014:33).

The purpose of this vignette is to contribute to the research field on artist-teachers in ACL and to develop a substantive theory about how individuals transform into artist-teachers in ACL, by writing about the people and the culture they are within (Ellis, 2004:26).

Art education allowed Emily to surround herself with like-minded people. She started to mix with others who were art-y and had that kind of mindset. She had found her clan. The art room was a place of sanctuary for Emily.

Chapter 1: Salad Days

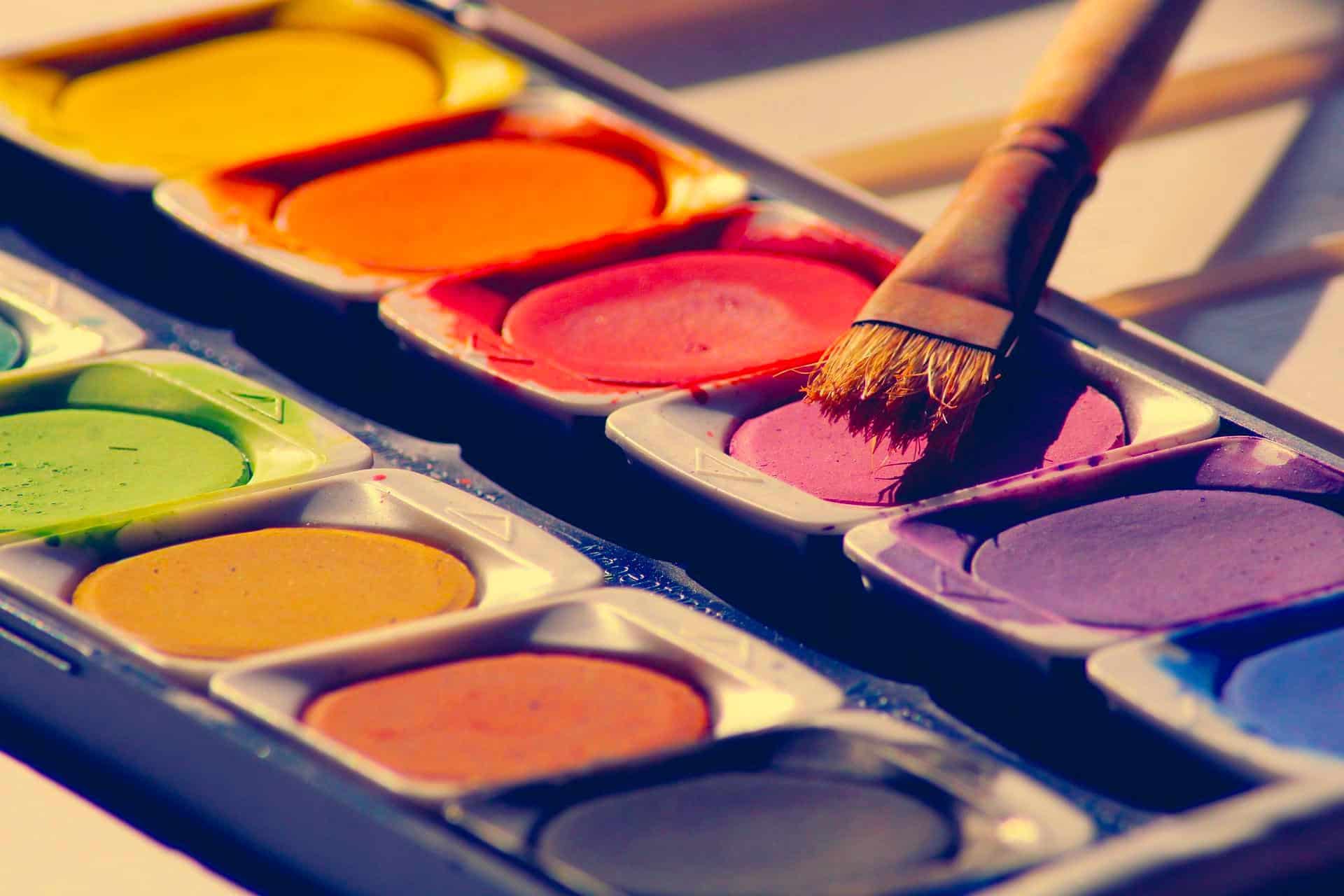

Emily has creativity in her blood; she has a dad that can draw and an uncle as an artist. She has a creative way about her; even as a child Emily liked doing things physically with her hands, including drawing and painting. Identifying as an artist came early to Emily. It was an identity connected to her education and being an art student, from secondary education to art college and beyond. She was drawn to an artistic way of life as it brought her enjoyment. Art allowed her to be free and expressive, and gave Emily a way to communicate with the world around her.

Her artistic talent was praised during her education. In primary school, she was singled out as being good at drawing. Later in her education, Emily’s teachers encouraged her to pursue art. In her art classes, she felt like an artist.

Art education allowed Emily to surround herself with like-minded people. She started to mix with others who were art-y and had that kind of mindset. She had found her clan. The art room was a place of sanctuary for Emily.

In school, Emily was more drawn to the creative subjects and knew that was the route she wanted to take. However, the road was not always smooth. Emily’s family negotiated encouraging her art and happiness, with making her aware of needing to be financially stable. Emily started to realise the financial implications of being an artist. A problem that came to the fore as she moved into adulthood; as she turned 18, the need to support herself increased.

Art was not necessarily viewed as a career by those around Emily, due to the socioeconomic background she was brought up in. It was viewed more as a hobby. While they did not always see eye to eye, Emily’s family still supported her. Because her family was not overly enthusiastic about her going off to art college, Emily felt she needed a safety net. Her Nana would get out drawings she had done to show her friends, and despite the discouragement to study art, her mum always turned up to her exhibitions and her graduation.

Teaching was Emily’s choice; no one had pushed her into the role. She had some informal teaching experience and enjoyed helping people. Besides, she had always thought about teaching, it was always on her agenda to do a little bit of both. She often wondered if teaching, like art, was in her blood. As she had family members who had previously taught, she felt like she would be good at it.

Chapter 2: Developing and Changing

After graduating from university, Emily moved back home and started to wonder “what now?” After some time, she got a job as a teaching assistant for a couple of years before moving onto the long-held role of teacher. When asked, Emily would tell you that she got into teaching totally accidentally; it was an opportunistic move. She was in the right place at the right time.

While Emily found her feet as a teacher, she was still proactive with her art practice. However, she had become a little disillusioned with the idea of being an artist. It was not as easy as she’d assumed it would be. Buying art materials, exhibiting, entry fees, traveling, everything was an expenditure. But she still enjoyed the glory that came with being an artist and showing her work.

Teaching was Emily’s choice; no one had pushed her into the role. She had some informal teaching experience and enjoyed helping people. Besides, she had always thought about teaching, it was always on her agenda to do a little bit of both. She often wondered if teaching, like art, was in her blood. As she had family members who had previously taught, she felt like she would be good at it. During this time there was a lot that happened. She gained her post-graduate certificate in education (PGCE) and started to identify as a teacher. Emily found herself surrounded by other teachers, which cemented this identity for her.

As a teacher, Emily hoped to make some changes and have a positive effect on learners. If art was about glory, teaching was about helping others. Teaching was a career. A profession. It was a way to make a living. It was teaching or working out how to sell a lot of paintings. She had bills to pay. Her family was supportive of the decision to “get a job”. But again, it was her choice.

Teaching took up most of Emily’s week, and she found it to be more stressful than artmaking. She experienced some nightmare years in the classroom, but overall felt she made progress with the learners. Teaching was pressurized and came with unrealistic workloads; things were overly complicated, and she missed being surrounded by other artists.

Becoming an artist-teacher in ACL was about progression: personally, financially, academically. But it was also about helping people.

Chapter 3: Home

Emily’s previous teaching gave her the experience and knowledge she needed to be able to apply for a position in Adult Community Learning (ACL). She was in the right place at the right time. Emily became an artist-teacher in ACL as she wanted to use her degree, she didn’t want to waste all those years of studying art. It was all very natural. She just went with the flow. Becoming an artist-teacher in ACL was about progression: personally, financially, academically. But it was also about helping people.

ACL differed from the other sectors she had taught in; she had started to feel less like a teacher and more like a social worker. However, Emily has discovered one pitfall of working in ACL: the uncertainty of employment. It dawned on Emily that she could do both. She didn’t have to be an artist or a teacher. In fact, she needs to be an artist to be an artist-teacher. She needs to do both to become the best she can be.

Emily has found working in ACL to be hyper-local, a massive change from her previous teaching positions. She is building a community and having conversations about art all day. She gets to be surrounded by peers that are doing the same thing as her, which has helped her to regain the artistic part of her identity. Emily now prefers having both identities; that’s who she wants to be.

As an artist-teacher, Emily has had to learn to negotiate her time. She has found that the ratio is a lot heavier on the teacher’s side. However, she still has an artist practice of her own, as she feels that she should practice what she preaches.

On day one of being an artist-teacher in ACL, Emily thought, “Yeah, OK. This is what I’m doing now.”

References

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H. and Ellis, C. (2014) Autoethnography (Understanding Qualitative Research. Oxford University Press.

Ellis, C. (1993) “Surviving the Loss of my Brother”, The Sociological Quarterly, 3(4). DIO: 10.4324/9780429259661-10.

Pace, S. (2012) “Writing the self into research: Using grounded theory analytic strategies in autoethnography”, TEXT Special Issue: Creativity: Cognition, Social and Cultural Perspectives, eds.

Ellis, C. (2004) The ethnographic I: a methodological novel about autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Featured Image by Kranich17 from Pixabay / The AutoEthnographer