Can We Live Autoethnography? Getting to Know Marieke Slovin Lewis

Marieke & Autoethnography

Dear friend, my name is Marieke, and I am an autoethnographer. Autoethnography has come to form the foundation for my life. It is a constant guiding presence, the lens through which I study who I am in relation with the world around me and the people with whom my path intersects. When considering how to introduce myself to The AutoEthnographer community, the voice of my inner critic began straight away, suggesting that there was really no way to share my authentic self in 500-1000 words. I should probably quit while I was behind. The writer spoke in soothing tones, assuring me this was possible and to pay the critic no heed. The musician balked, grumbling a protest that I was not offering a melodic introduction. And so it went for several weeks until I finally found an internally quiet(er) moment to sit down and see how I might describe myself on a sunny Arizona morning in the last day of October 2022. It is with delight and some trepidation that I share this introduction. It is my hope that these words will serve as the beginning of an ongoing dialogue about what it means to live autoethnography.

Becoming A Musician

I grew up in the 80s before the Internet or cell phones (gasp) and spent a good portion of my childhood, playing outdoors and decorating my room with leaves and rocks and branches, and being told by supposed friends that my side ponytail was wanting in comparison to their own. In high school, I ran cross country and spent hours, roller blading with friends, thinking I was very cool indeed when I added grind plates to the inside edges, cruised down staircases, and slid across pipes balanced precariously against cement blocks in our driveways.

My main identity throughout my childhood was that of a musician. My mother tongue might be English, but the second language I learned was classical music on the piano. From the time I was five and managed to sit at a piano at a friend’s house and begin banging on the keys, my parents had encouraged a burgeoning love of music. I studied first with a series of Russian teachers, one of who would place her hands atop mine and proceed to bang on my hands on the keys to show me how my playing “sounded.” I eventually graduated to kinder teachers. I was always told that I was musically gifted but that I was not meant to add my own creative interpretation to classical pieces I performed.

Becoming a Ranger

It was in leaving for university that my identity as a wanderer and world traveler began to take shape and my disenchantment with classical music took hold. While I loved the piano, I found myself constricted by the strict nature of the classical music world. Piece were to be performed exactly as they were written and without creation interpretation or expression. This combined with the dawning realization that practicing all day every day would not only inhibit my ability to discover my authentic self but also limit my ability to pursue other creative interests, I found myself relinquishing my identity as a musician in order to study French language and travel to Mali, Hungary, and Russia.

I began my official “career” as an environmental educator, driving across the country from Maine to Washington state, following unpaid internships to seasonal jobs and moving up the ladder to become a National Park Service Ranger. I spent a year teaching English in France and returned to the mountains of the Pacific Northwest to continue my life as a park ranger. I worked at national parks in Washington state, Alaska, and Massachusetts. While I loved the variety and versatility of the park ranger path, I began to realize that the life of a government employee mirrored the limitations I experienced in the stringent, structured world of classical music.

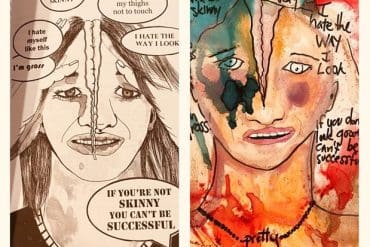

Self-Sustainability and Story-to-Song

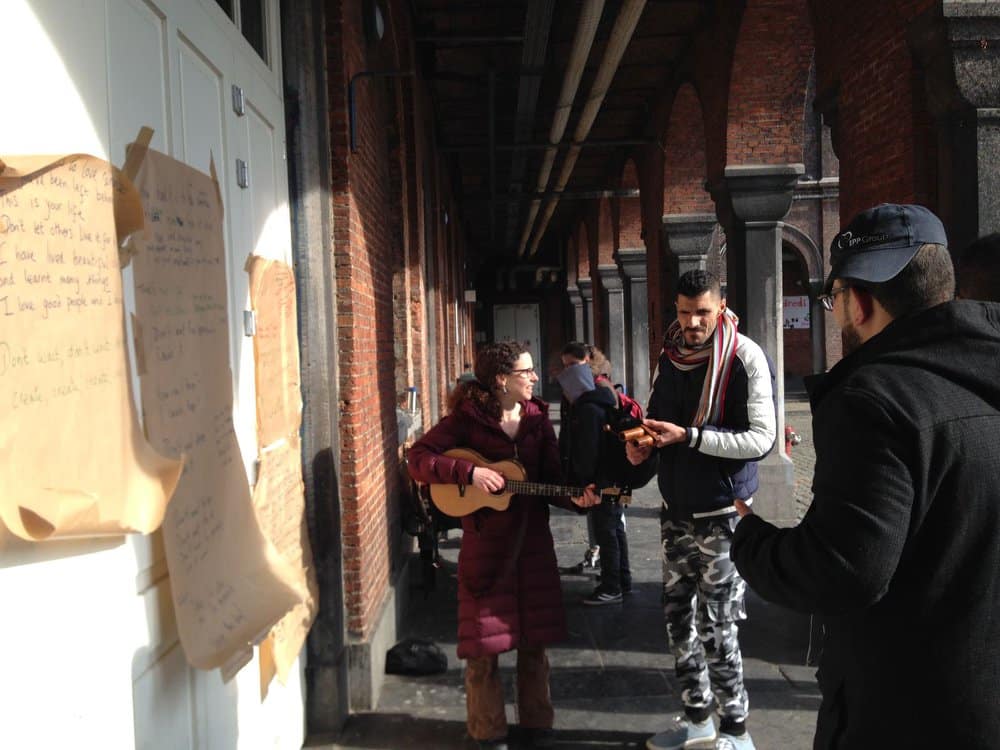

I discovered autoethnography as a doctoral student in a Sustainability Education program at Prescott College in Arizona. It was in joining a community where I was seen and celebrated for being my authentic self that a paradigm shift began. My research came to focus on a concept I called “self-sustainability,” which was the notion that creating sustainability at a global level required beginning with the individual. I wrote an autoethnography in which I shared the steps I followed on my own path to creating a sustainable life. I left government service and began actively rediscovering my identity as a musician in a role that allowed me to embrace and embody my authentic Self. I studied the beneficial effects of participatory art for creating opportunities for self-sustainability. To this end, I worked closely with a member of my cohort to develop a method of songwriting called “Story-to-Song” (STS). Through STS, we guided people through a collaborative process of shaping their spoken stories into songs.

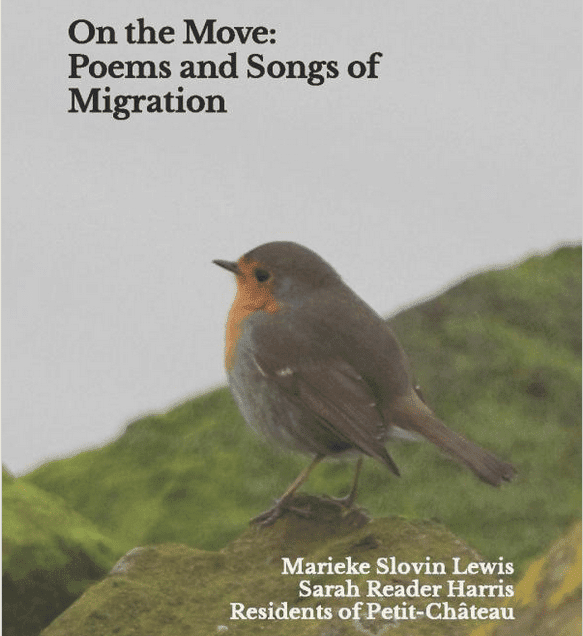

I have spent the better part of the past 10 years, writing music from stories. I have written songs from oral histories, historic documents, and with people of all ages from around the world. It is this path I have followed as an autoethnographic songwriter that I wish to share with you in this series. I am looking forward to sharing the origins of the Story-to-Song method and the people and stories behind the songs.

I hope you will join me and share your own voice and stories.

Melodically yours,

Marieke

Editor’s Note: The AutoEthnographer may be compensated for clicks on affiliate links.

Featured image by EFES for Pixabay I The AutoEthnographer

Dr. Marieke Slovin Lewis is a participatory artist, writer, musician, and songwriter. Marieke holds a PhD in Sustainability Education. Her doctoral research focused largely on a concept she called "self-sustainability," the idea that to create sustainability at the global level requires beginning with each individual person. She also focused on the beneficial effects of participatory art for creating opportunities for self-sustainability, co-creating a method of songwriting called Story-to-Song (STS). Through STS, a person is guided through the collaborative, creative process of shaping a story from their lived experience into a song. Marieke has employed the STS method with people from all over the world. Her “Migration Songs” project, writing songs with refugees and asylum seekers in Brussels, Belgium, was shortlisted for the 2021 Amateo Award for Arts Participation Projects in Europe. Her music has been highlighted in several publications and podcasts. In addition to writing music, Marieke is a bird enthusiast and wandering soul. She currently lives in Prescott, Arizona with her husband, husky, and two cats. https://guidingsong.com/