Limited (Or No) Reproductive Rights through Generations: This Solitary Choice

Author’s Memo

Born just four years after the passing of Roe vs. Wade, I’d always believed that I had the right to choose when to have a child—right up until I tried to have one. The process of seeking pregnancy alone (by necessity, not choice) showed me how limited reproductive rights in the U.S. truly are—even before the recent loss of Roe vs. Wade, that policy that had so shaped my generation’s belief in our bodily autonomy. Like many of my peers, I had long believed that such autonomy was tied to individual choice: the same rhetorics that had guided the pro-Roe movement itself.

Although I had also read critiques of an over-reliance on reproductive “choice” as opposed to a focus on equity-based rights (i.e. supporting access to reproductive planning for all women, not just those with economic and often race-based privilege), it wasn’t until my own lived experience caught up with such questions that I understood more fully how true it is that access to reproductive agency is collective, rather than individual; and how we need not only legal protection, but also strong and supportive communities, for women everywhere to have the means of expressing autonomy over their bodies.

This same lived experience has also taken me back to the page, now employing autoethnography as a means of sharing the cultural critiques that have been part of my own coping process. As a writer, the ethnographic impulse has been with me for a long time; and I’ve written from both field work and oral history, projects that felt important at the time, even as they remained relatively safe: analytic, carefully crafted, academic. It wasn’t until later, though, when I found myself in much less certain contexts, that I needed something more. Neither simply personal or political, my new work doesn’t fit well within the margins of any genre I’ve used before, leading me instead toward autoethnography, as what I strive for now is to bring certain experiences to life: to “evoke” them for the reader.

Specifically, “This Solitary Choice,” offers cultural critiques of fertility treatments, couched alongside similar considerations of abortion: arguably two sides of the same coin. Privatized and for-profit, the fertility industry remains largely unregulated or critiqued; and, like the original “choice” movement for abortion access, it is most accessible to those with privilege, particularly in terms of economic status and heterosexual marriage. As a single woman stepping trepidatiously into this context, I found dynamics so new, and micro-aggression so invisible, that I quickly realized we don’t yet have language to describe them—or, in some cases, awareness of some of the foundational questions that can affect pregnancies, even when they are desired.

My meditative essay reflects on these questions alongside related histories of abortion—including several in my own family history—identifying ways that political and commercial policies have often diminished women’s agency by drawing divisions among us, leading to the kind of alienation and solitude that I felt during my own process of trying to become a mother. Calling attention to that loneliness, “This Solitary Choice” highlights the commensurate need for community throughout all facets of reproductive planning. Even while it may seem possible to some to support reproductive choice conceptually, assuming that their own lives will never be directly affected, my own experience as a white, educated, middle-class woman trying to get pregnant taught me that bodily autonomy is not necessarily what I had assumed, and that our most enduring related questions are not individual so much as shared.

Limited (Or No) Reproductive Rights through Generations: This Solitary Choice

At six weeks, my grandmother hadn’t known that she was pregnant. Not the first time, nor the second, or the third. At some point, she’d lost track of how many pregnancies—whether by seduction or force—there had been in her teens. Living in a shack outside of Depression-era Austin, she hadn’t had things like calendars and clocks to track her cycles, or locks on doors to keep men out or in. When pregnancies came, as inevitably they did, she’d found ways of ending them. “What else could I do?”

Hearing her stories first during my own teenaged years, I’d had no answer. What, after all, can an orphaned girl do to protect her body, or her future? What power or autonomy did she have? Coming of age in the 1930’s, her youth was starkly different from my own—stable, middle class, and full of promise—though I didn’t yet know how easily a woman might find herself alone. Her, or me. And how many different forms such loneliness might take.

In my grandmother’s case, she wasn’t yet sixteen when both parents had died within six months of each other. This left her three younger siblings to raise. “They were my family,” she’d told me, still glassy-eyed all these years later. “I didn’t want to lose them.” And so easily, she could have. Like so many women in the Great Depression, she truly couldn’t afford another mouth to feed.

Back then, there wasn’t much she’d had control over, beyond seeking help from friends. All those other women who’d advised her on how things could be done, if and when it was needed. “People knew how,” she’d explained: tinctures and remedies to stop a pregnancy that might otherwise have sent you to the poor house. “We all helped each other.” Because, back then, the U.S. largely turned a blind eye to such things—even in Texas. Struggling economically, people couldn’t afford large families during the Depression; so abortion, while not quite legal, also wasn’t quite forbidden. “There was always a way out,” she’d lain a hand across mine, telling me these stories. “And you were never alone.”

This did not mean she didn’t want children. She did—and eventually had six of them. “But back then, what choice did I have?”. She’d looked up at me meaningfully, her oldest granddaughter—the one who, eventually, would hope to name a child for her—because she knew that I do, or should. Decades later, born shortly after the passing of Roe vs. Wade, I’d been assured that my body, and my future, were mine to determine—so unlike my grandmother. Or my gay mother, who birthed two children in a straight marriage that she left twenty years later. Or even my stepmother, who struggled to finish high school after birthing her son at seventeen.

But you—you could do anything, I was told, time and again.

And indeed, it seemed that I should seek everything—career, family, and the right time and place—that I owed as much to all those women before me who hadn’t had the means. But doing so turned out to be much more difficult than any of us had guessed. As the men I gave myself to left, one after another, to pursue their own careers—and the men I worked with built careers alongside wives and families—my options narrowed as I neared forty. Like my grandmother, I wanted children—and like her, I was alone.

But that shouldn’t stop you, people around me insisted.

Of course not, my head shook, though that choice—a childless life vs. raising a child alone—wasn’t one I’d ever hoped to make.

But it should empower you. Though that promise, too, didn’t quite ring true—perhaps because my access to fertility treatments is likewise limited. Even as a tenured professor at a Catholic university—with its consistent insistence on the value of life—I have no health insurance to cover the costs of becoming pregnant.

Or perhaps it is because, even as I slowly find, through a series of second and third jobs, a means of paying for that process, no one can predict my chances of success. “But how can you not know if it’s worth trying?” The financial costs, after all, are staggering—a year’s salary. But the answer is simple. No statistics are kept on single women—only on those married women who struggle to conceive.

Or, too, perhaps it is because, even if I am successful, I learn increasingly that, whether or not people intend to, they will judge me. “Are you ashamed?” one doctor asks as I seek her help.

Ashamed? Of being alone? No—not, at least, until she suggests it. Seeking pregnancy on my own, there are many other things I feel—frightened, isolated, fatigued—though now there is this, too. The shameful reminder that our implicit standards for women—to marry, to procreate—are so often out of reach.

And so, I do not feel empowered, or reassured. What I feel most is alone.

But there must, people around me assume, be more women like you.

Which, of course, is true. Their collective name, I learn, is Choice Moms: women, primarily middleclass, raising children on their own. Meeting them gives me heart—and also pause. Although I’m grateful to find, as my grandmother had, women similarly situated, their title troubles me: Choice Moms. Why, I wonder, can we claim legitimacy only by distancing ourselves from other women. All those 11 million single mothers in this country who hadn’t had a choice? Millions of women raising children alone due to divorce or rape or abandonment or abuse? Women like my grandmother, my mother, my stepmother—truly, all the women I’d come from.

Why, moreover, had we all become so divided? For most of history, women have worked together: midwives helping to spur and manage pregnancies, to deliver or prevent them. Not until the American Medical Association (Ravitz, 2016) was founded in 1847 (Blakemore, 2018) were midwives removed from the profession, to better ensure the salaries of male physicians; and not until male politicians worried about waning blocks of white voters (Goodwin, 2020) was abortion initially criminalized (DiBranco, 2020) a few decades later. These divisions, then—first, women from each other, and then from their own bodies—are not accidental. And so, too, I understand that my own loneliness is not accidental—or this sadness as I wait, month by month, for my body to create new life on its own.

But what is that cost of such sadness? Or division? Alone, I work extra jobs—secretly and chagrined—to afford fertility treatments. Alone, I wait through three years of delays and near misses, until I, alone, feel the deep and utter thrill of the process finally working—my child! my love! my future! at last!—and then the solitary devastation as that child, at the end of it all, miscarries. Alone now, I carry my grief, wondering how things might have been different? How, without this extra strain and stress, this silence and shame, my body might have found a way to hold onto that new life I’d so hoped to create.

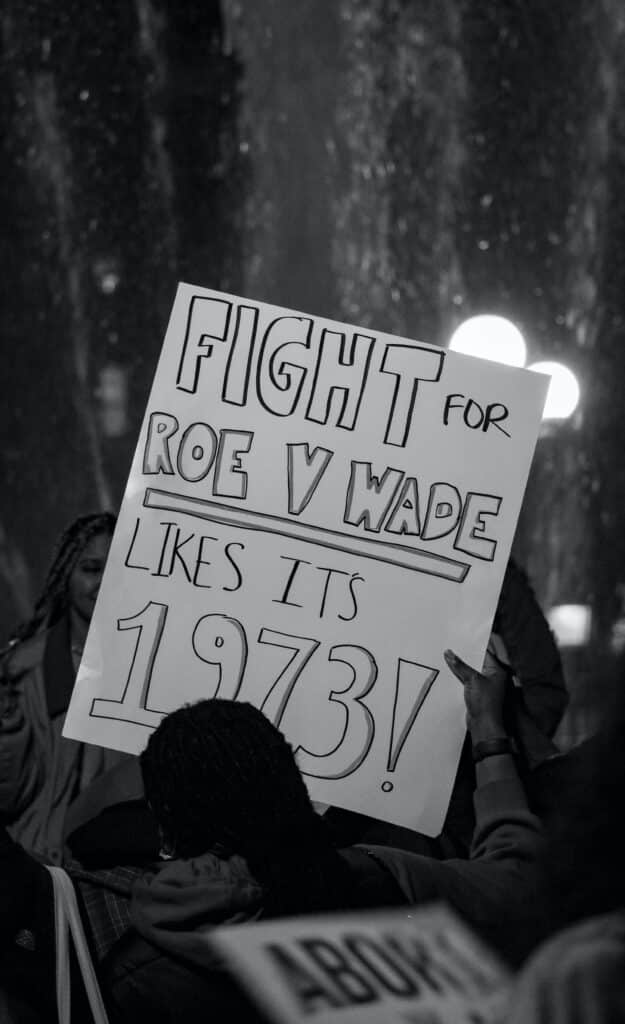

But, solitary as they feel, these questions are not mine alone. And even as I grieve, our nation ignites again in debates of life vs. choice. As though they were ever separate, or could be. But divisions, history has taught us, are effective means of limiting our agency—of keeping us alone. And so, as my body remains quiet, producing no child—no namesake for my grandmother, gone now a century after her own birth shortly before Texas had banned all those abortions that she would inevitably seek. I recognize, finally, the error in assuming that personal agency must be individual. Instead, I understand increasingly how choice is contingent—necessary, yes, though not solitary. How even bodily autonomy seeks community—some kind of collective whole—to bring us back to the fullness of our lives.

For her part, my grandmother, for all she endured, only complained once. Not about those early injustices or assaults, but about what happened later, once she’d married, just before my grandfather had left for war. Pregnant from their wedding night, she’d needed to end it, he’d insisted, handing her a slip of paper and seventy-five crisp dollar bills. “Now’s not the time,” he’d made her promise, though they wanted children, and eventually raised half a dozen of them. But that last abortion—walking those quiet stairs to the hidden clinic, knocking on that solitary door to be received by a nameless doctor who would take that nascent life from her, then swear her to utter secrecy—was the only one she’d ever resent. And the only one she’d had to face alone.

References

Blakemore, E. (2018, January 22). The criminalization of abortion began as a business tactic. History.com. Retrieved August 18, 2022, from https://www.history.com/news/the-criminalization-of-abortion-began-as-a-business-tactic

DiBranco, A. (2020, February 3). The long history of the anti-abortion movement’s links to white supremacists. The Nation. Retrieved August 18, 2022, from https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/anti-abortion-white-supremacy/

Goodwin, M. (2020, July 1). The racist history of abortion and midwifery bans: News & commentary. American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved August 18, 2022, from https://www.aclu.org/news/racial-justice/the-racist-history-of-abortion-and-midwifery-bans

Ravitz, J. (2016, June 27). The surprising history of abortion in the United States. CNN. Retrieved August 18, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2016/06/23/health/abortion-history-in-united-states

Credits

Featured Image of people during a protest holding up signs by Gayatri Maltohra for Unsplash

Black and white image by Emma Guliani for Pexels

Colorful sign held by a group of people by Gayatri Malhotra for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work? Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Recipient of awards from Fulbright and the NEH, Susan V. Meyers directs Seattle University’s Creative Writing Program. Her novel Failing the Trapeze won the Nilsen award, and other work has recently appeared in Creative Nonfiction, The Rumpus, HuffPost, New Orleans Review, Calyx, and The Minnesota Review.