Emerging Immigrant’s Accents: This is the Spoken Birthright of Bicultural Spanglish

Author’s Memo

This is a memoir about my family’s relationship to both English and Spanish. Spanning from my abuela – who speaks with an accent and came to the US in her 20s – through my mother a true bilingual, and to me a US born who has a hard time understanding her own Spanish. My lack of Spanish has impacted my view of myself as a Peruvian, just as my abuela’s accent makes it hard for her to consider herself an American. How does language impact our self image as we come to understand ourselves and our cultural beings?

Spanning from my abuela – who speaks with an accent and came to the US in her 20s – through my mother a true bilingual, and to me a US born who has a hard time understanding her own Spanish.

Proven Reasons for My Abuela’s Surviving Spanish

My abuela’s understanding of language did not change until she came to the United States and became an immigrant. Her language went from being solely Spanish bicultural: to including a whole new definition of words and extension of herself. She learned how to ask strangers for directions when she barely knew what “right” or “left” meant and she learned what it meant to speak with an accent. She learned how the U.S. looks down on people who have: Peruvian ponchos, dark skin, and talk in a way that is “broken.”

Still, her home was where Spanish was fluent, as it was with her new Peruvian family that had adopted her in Michigan. So mi mama was also raised with Spanish in the home. Her Spanish was different though. She could speak fluently but her ability to spell, read, or write was practically non-existent. If she were to be tested in Spanish at the academic level – she would fail. Perhaps be labeled as a “long term English Language Learner.”

My lack of Spanish has impacted my view of myself as a Peruvian, just as my abuela’s accent makes it hard for her to consider herself an American. How does language impact our self image as we come to understand ourselves and our cultural beings?

Simplified Theorist’s Argument and My Compromises

As Flores, Kleyn, and Menken say (2015) “We argue that LTELL has become synonymous with and has replaced terms such as semilingual, which have fallen out of favor for their “politically incorrect” nature” (114). Whether semilingual or an LTELL, both meaning not being entirely proficient in two languages. Her English is good, she took advanced medical courses in college and helps edit my papers, but it is still broken. When she tries to say “rose colored glasses” she instead says things like “pink shades” and blames her immigrant upbringing.

My Spanish is less proficient than my abuela’s English. I learned a few key phrases growing up but I resisted my mother’s attempts to give me her language. When she would speak to me in Spanish I would go to my sibling or my father to speak English. Eventually she gave up. By the time I realized its importance it was too late to acquire another language naturally. When I started learning in school I would speak with my mother to help me. The problem was I was a visual learner. So when she would tell me new words I would ask her to spell them for me. She would flounder about until something was created that was nowhere near the original word. When I asked her what the word was unconjugated, why she used “estar” instead of “ser,” she would shrug her shoulders.

“I don’t know why, but I know that’s right.” She would tell me.

Unconditional Knowledge and the Holes in Me

I would have protested except I understood her completely. While I had never completely learned Spanish, I had been raised around it. I knew several key phrases and certain rules without knowing how to explain them. “Por” and “para” being the best example. When my classmates struggled with which one to use they would ask me for help, I would tell them the right answer and they would ask me why I used that one. I would tell them the same thing with a shrug.

“I don’t know why, but I know that’s right.”

My lack of Spanish created a hole in my identity once I became an adult for many reasons. In part because I had finally met my cousins in Peru but yet could barely talk to them. Even then, only to the ones who knew a lot of English, I would visit my vieja who was nearly 100 years old and whose memory was fading. I only knew what stories she was telling me was because she had told them to me so many times before. I learned how to tell her who I was in Spanish for every five minutes when she would ask me.

Compromised Judgement and More Noted Theorists

My lack of Spanish also led to the judgement. I once briefly dated a boy (he was a man but I will call him a boy) who said:

“Anyone who doesn’t know their families home language should be ashamed of themselves.”

I wish I had told him that we were not all so privileged to be sent home to China for six months every year. How he shouldn’t judge others just because they are not up to his standard. But instead, I internalized it. I felt the pressure of not knowing my mother’s native language.

“I’m Peruvian.”

“So you speak Spanish?”

Is what I am always greeted with. Gail Shuck (2006) discusses how “The relationship between talk about language and talk about race is not coincidental, nor are the similarities in those discourses superficial” (p. 260). She says simply because English Language Learners do not speak English, many are looked down upon for not being of the predominant race. I believe the reverse is also true. I find myself being looked upon as being only a part of the dominant race because I speak English. My Peruvian blood is erased because I do not know how to hold a conversation in my abuela’s native language.

Unparalleled Teaching Crisis and the Weight of an Immigrant

I get asked about my racial identity in conjunction with that of my students’. It is something I worry about when I teach Latin American literature. I know there will come a day when I have students in my class who are more Latina/o than I am. I wonder how they will handle me showing them the literary authors I have come to study. Especially, when I cannot do so in their native language. My birth name is White, my skin tone is White, my language is White.

Motha (2014) says that “a definition of Whiteness is elusive because it is first and foremost understood in terms of what it is not, that is, a category of racial identity that is ‘not racial minority’ or ‘not person of color’” (38). Meaning anyone who looks at me and deems me White erases the parts of me that have grown up a bicultural existence.

I have felt the weight of family that lives continents away:I have felt the weight of being an immigrant’s daughter. I have felt the weight of being torn between two worlds. If I were to tell you about the language of my tongue it would be heavily accented and trilingual. Spanish, English, and everything that exists in between. My dream is to one day be able to bounce between Spanish and English effortlessly and when I am angry. To do so to my children, who will understand me. I keep putting off this dream for others – pursuing a doctorate, raising a puppy, moving across the country multiple times – but that does not mean it does not exist.

Language Barriers and What Does Love Mean

That does not mean I don’t feel the weight of all those languages pressing on the back of my skull when hopeful eyes stare into mine and I can only gaze back in uncertainty. I am traveling soon to my cousins wedding in Ecuador. She has married a man more Latino than anyone in our generation of familia. I wonder how much I will be able to converse with the relatives I will meet there. I wait in terror at the thought of them being disappointed. Will they talk behind my back about how I should know my abuela’s language? How I should know what “Te amo” means not because I have learned it, but because I was raised to know it.

I wish I had not fought my mother so much. But now I will have to learn the hard way, and only hope that my children will allow me to teach them. So that one day they will not know what it means to not be fluent.

The Weight of Fluency

To not be fluent is to cock my head whenever I recognize Spanish, in both understanding and confusion and to not be fluent is to have Spanish speakers come up to me hopeful, only for me to turn them away. To not be fluent is to question what exists between my head, my tongue, and my pulse and where the words that flow out of me should actually go.

Not being fluent is to have an ache in my gut.

I wonder if it exists this way for my abuela, just with English instead.

Credits

Featured image of a Peruvian Dancer By Federico Scarionati for Unsplash

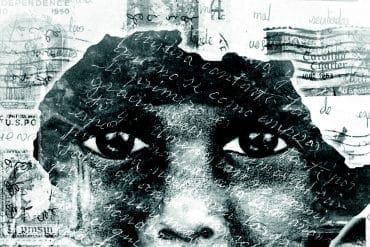

An Image of child drawings by Anne Nygard for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

I am a third year in my English with a creative writing emphasis PhD at ISU. I obtained my masters from CalArts and have published several short pieces in Stirling Lit, Club Plum, and Entropy as well as a novella in Big Fiction Magazine. I enjoy long walks with my King Charles and call my mom daily.