TATTOO MEANINGS: LOVE, LOSS, & AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC MUSINGS

Author’s Memo

Understanding ‘tattoo meanings’ is not as straightforward as the literature might lead us to believe. My PhD research (McDade, 2021) utilised my tattooing practice and autoethnographic accounts of practice as a research method in order to increase understanding of contemporary western tattooing as a practice and profession”. Tattoo historian Matt Lodder has described the majority of the accumulated literature on tattooing as “research tourism”, in which academics use tattooing as, “…a diversion or offshoot from their primary research angle” (in TTTism & Schonberger, 2018, p. 503).

Much of the academic work on tattooing is primarily concerned with the tattooee rather than the tattooist, and asks questions regarding tattoo motivation, marketplace, social behaviour, etc. It has been largely been conducted by interviewing people with tattoos and asking questions to the tone of, “What does your tattoo mean?” This method has problems in that it fails to recognize the variability of tattoo outcomes, clientele, bodily placement (and a range of other factors), and fails to acknowledge that tattoos are produced by practitioners who may have their own ideas about the meaning of the subject matter, and it fails to appreciate the contingency of human experience and existence which can affect how meaning becomes layered.

This article sets out to enrich understanding of the complexity of ‘meaning’ when discussing tattooing, utilising an autoethnographic account of my experiences of obtaining a tattoo after the loss of my dad. Contributing themes to tattoo meaning are proposed to include shifting personal relationships (with both the figure referenced in the tattoo outcome and tattooist producing it), significant changes in personal and professional circumstances, and the presence of existing tattoos. The musings leading to the production of this article were initiated through my professional experience as a tattooist in North-East England, in which I have tattooed hundreds of individuals with a variety of subject matter. Through the evocative presentation of the variable factors that contribute to meaning, substantiated by professional tattooing experience, the aim is to dispel the notion of the ‘tattoo meaning’ being deducible to something stagnant and possible to examine in the straight-forward manner that it has repeatedly been subject to, and present it as contingent, variable, and resistant of formal classification.

The meaning of the tattoo is not fully in the realm of communicable expression due to the complexity of human existence and the necessity of language to abstract and distil into mere words what are layered, intertwined, and shifting human emotions.

What do we mean when we talk about tattoo ‘meaning’?

While examining numerous articles surrounding meaning and identity within tattoos (including Kjeldgaard & Bengtsson, 2005; Carmen et al., 2012; Sundberg & Kjellman, 2018) I noted the tendency for simplification of findings and the implication of meaning as fixed, or as cultural studies scholar Nikki Sullivan terms it, ‘dermal diagnosis’ (2001, p. 17); as if a tattoo received at the age of eighteen means the same thing to the wearer as it does at the age of forty. The straight-forward presentation of meaning of tattoos in academic literature fails to recognise layers of nuance that exist as a motivation for tattoo acquisition.

When conducting research involving interviews with those attaining tattoos on their specific motivation, the assumption is that there is some clear-cut meaning that is in the realms of communicable vocalised explanation. It is also assumed that the design denotes singular authorship; as if the way the tattoo appears on the body is the result of an individual interaction, rather than a collaborative and contingent process between tattooist and client as I have contended to be the case (McDade, 2022). In what follows, I provide an example of the complexity of meaning that can be assigned to tattoo outcomes based on my personal experience as a tattooee, and tattooist.

I considered the nuance of tattooing meaning by drawing upon my own experiences of being tattooed with a subject matter that is sentimental in nature; my deceased dad’s handwriting. My dad suffered from severe depression and subsequently, alcoholism, from an early age in his life. In the 1970s, he founded a progressive rock band named, Cirkus (in reference to a King Crimson track, from the album Lizard) in which he was the main song writer and drummer/backing vocalist. The band enjoyed relative success, releasing their first studio album in 1973. Growing up, my dad would often play the music he had created on Saturdays when I would go and visit him, since his separation from my mam at a very early age. I remember not being particularly interested in the music, which was an extension of the turbulent relationship with him that I had more generally due to his absence and the feeling of discomfort I had in being around a guardian figure who was inebriated, without understanding what inebriation really was.

Though my dad didn’t like tattoos, he always advocated personal sovereignty, and so never discouraged my choice to become tattooed.

As I grew older and began to become interested in music and learning to play the guitar, I turned to my dad for lessons. He was able to teach me some basic chords and was enthusiastic about my interest, however his ongoing relationship with alcohol had led to a diminishment of skills, and ability to teach. This then led to further frustration, continued depression, and a stronger reliance on drinking. My relationship with my dad fluctuated through adolescence, but my visits to see him eventually became more out of desire than duty. We introduced each other to numerous musicians, and I would often show him new pieces of music I had written with the sincere desire to impress him, and I trusted in his musical knowledge and feedback. He was always very supportive.

As I began to become to tattooed on my right arm over fourteen years ago, I formed a good relationship with the tattooist. He was around fifteen years my senior, and in addition to representing the romance of tattooing that I found so alluring, I admired his ability to lead a lifestyle that allowed him to engage with a creative medium and pursue his own interests. Though not old enough to be a paternal figure to me at that age, he played a significant impact in my personal growth through the example of an alternative adulthood that he represented in which work was not resented, and that I aspired to achieve for myself. He created a full sleeve over the course of a year and a half, with one of the latter pieces being a scroll of paper in a bottle on my inner forearm. The sleeve is in a traditional-western inspired style with no specific meaning attributed to the subject matter for the most part, which was chosen based on visual appreciation and resonance with the practitioner. Though my dad didn’t like tattoos, he always advocated personal sovereignty, and so never discouraged my choice to become tattooed.

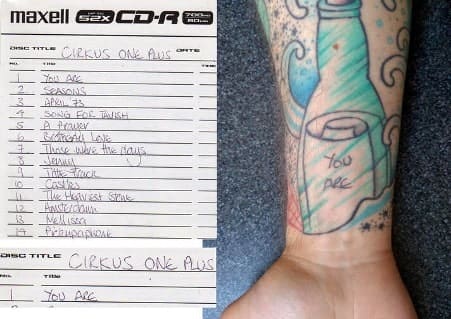

As the years passed, my relationship with my dad matured, and he went through phases of becoming more and less ill. I became more appreciative of his music and felt like I finally understood it after practising music myself for a number of years. I actively listened to the CD of his first album ‘one’ and resonated specifically with the first track, titled You Are. The original LP pressing of his album is a collector’s items amongst prog-rock connoisseurs and is very rare and now fairly valuable. My dad sold both his records and the CD versions of his music for money to survive, but had made sure he made a CD-R copy before doing so, with hand written track listings. I interpreted this act to be representative of the extremity of his situation; he created an authentic and creative expression of beauty that symbolised a significant achievement, that was only ever going to monetarily increase in value, but he was in a position where he needed to trade this for money for his survival and sustenance of his addictions.

As he grew older, his resistance to his own ageing furthered the tendency to drink and the walls of his rented apartment in which he lived alone became more tainted with stagnancy and sadness. He died of heart failure, after what is believed to have been a deliberate decision to no longer take his medication, on Easter Sunday 2016, and his body was found on the floor of his passageway four days later by my sister. She had a key and visited after not hearing from him when trying to make contact and becoming concerned. His funeral commenced around a week later, and I carried the side of his coffin containing his body into the church alongside his brother and my cousins, while the track ‘You Are’ played.

After working in the studio for around eight months and dealing with the grievance process of my dad in the various stages, I made the decision to have his handwriting tattooed on me. The handwriting was found on the sleeve of the CD-R of his first album, written in biro, and was visually distinctive to me from having seen it in every birthday card written to me up until the age of twenty-six when he died.

I hadn’t fully accepted the grieving process until this point. As the ascension of tones of the introduction to the song played in rhythm with the pace of my footsteps, accompanied by the weight of my dad’s body on my shoulders and the years of burdened suffering that it had housed, I felt a wave of emotion pass through my body in perfect synchronisation, to be expelled in an outpouring of cathartic tears as I took my seat. The song played out as I waited for the service to commence and my grief to begin its course.

Shortly after my dad’s death, I made the decision to hand in my notice for my job as a content editor in the fashion industry (a position I had no interest in and had taken solely as a means of generating income to survive), and travel to Asia where I had previously felt at home, until I ran out of the small pot of money I had saved. My hope was that I would find employment in Thailand, Indonesia, or India, and be able to live there for some time, and the decision to go was inspired by the reminder of the impermanence of all things that my dad’s death at the age of sixty-two presented. When I ran out of money from traveling after three months, I returned to Sunderland. In an effort to not live an existence based on fear in favour of one based on fulfilment, I reached out to the owner of the Studio in which I now work as a tattooist.

I was originally introduced to the studio owner who I contacted fourteen years prior, on the recommendation of the tattooist who had completed my sleeve after I requested a realistic style tattoo. He told me that there was another tattooist who had recently opened a private studio and was breaking new ground with the work he was producing. Although my existing tattooist could have taken the money and executed the tattoo, he recommended an alternative tattooist based on what served my interests, over his own (an unconventional notion in preceding decades of tattooing).

After meeting the studio owner, I went on to get both my foot and full left sleeve tattooed by him and formed another centrally important figure in my personal development. When asking for a tattoo apprenticeship, he had told me to go to university and do a course relating to visual arts, and then he could consider the position based on what I had learned. After progressing from a foundation degree to a master’s degree in illustration over the course of five years, I felt that I wanted to pursue a career and generate enough income to live independent of my mam, and so sought a full-time job rather than pursuing tattooing.

My dad’s handwriting on the CD-R of his album ‘One Plus’ (left), which was used to inform the text tattoo added to the existing tattoos on my forearm (right)

When returned home—on a whim—I contacted the studio owner, who was now in charge of a studio of over ten tattooists and internationally award-winning tattooist, as well as inventor/product developer. When I asked if he was considering an apprentice, he told me that the same thought had crossed his mind specifically relating to me, and he offered me a position. In this studio, the tattooist who completed my first sleeve was now a full time resident, and I was able to learn from him amongst numerous highly-skilled others. Six months later, I created my first tattoo on the studio owners arm who had given me the apprentice role, which to this day is the most technically poor and simultaneously meaningful tattoo I’ve created to date.

After working in the studio for around eight months and dealing with the grievance process of my dad in the various stages, I made the decision to have his handwriting tattooed on me. The handwriting was found on the sleeve of the CD-R of his first album, written in biro, and was visually distinctive to me from having seen it in every birthday card written to me up until the age of twenty-six when he died. The first track on the album titled, You Are, seemed the most appropriate piece of text to have tattooed for reasons beyond it being my favourite track alone—the track was symbolic of the establishment of a connection with my dad beyond the father-son relationship exclusively, as it was the turning point from which I began to admire and see value in his skillset. It was also the track that acted as a vehicle through which I navigated into the first stages of my grievance process during his funeral. The open-ended nature of the words feels like an answer from him to questions that I haven’t yet asked, that can be interpreted in multiple ways with the consideration of what he might say.

I opted for the same tattooist who completed the scroll of paper in a bottle tattoo for me over fourteen years prior to do the piece. The scroll of paper in the bottle was indicative of a message, but the content of the message had thus far not been known. I had the words put into the scroll with watered-down black ink, to emulate handwriting and appeared consistent with the tones of the rest of the earlier executed tattoo. It was important to me to have the piece completed by the same tattooist who created the original piece, due to his impact on my path and my associated memories of a time in which I was becoming tattooed and being birthed into adulthood into a world that still had my dad in it. The tattoo being completed by that particular tattooist after a significant period of time had passed and changes in our lives had occurred—in a context where I was now working alongside figures who had already unknowingly shaped my personal growth—contributed a layer of nuance to the ‘meaning’ of the piece.

The meaning of the tattoo is not fully in the realm of communicable expression due to the complexity of human existence and the necessity of language to abstract and distill into mere words what are layered, intertwined, and shifting human emotions. The link between tattooing as a medium with embodied meaningful imagery is only partly accurate, and many tattoos are obtained for their visual properties exclusively. The understanding of tattoo meaning that is presented in academic literature can only partly represent the ways in which meaning comes into and out of focus for the tattooee from the time of production. While this example is specific to me as an individual and my own biographical background, it can demonstrate how ‘meaning’ cannot be simplified in the way that it currently is in the literature on the topic.

References

Carmen, R. A., Guitar, A. E., & Dillon, H. M. (2012). Ultimate answers to proximate questions: The evolutionary motivations behind tattoos and body piercings in popular culture. Review of General Psychology, 16(2), 134–143. pdh. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027908

Kjeldgaard, D., & Bengtsson, A. (2005). Consuming the Fashion Tattoo. Advances in Consumer Research, 32(1), 172–177. bsh.

McDade, A. (2021). Beyond the Epidermis: A practical investigation into contemporary western tattooing [Doctoral, University of Sunderland]. https://doi.org/10/13599%202.pdf

Aurhor. (2022). Contemporary Western Tattooing as an Inherently Collaborative Practice: The Contingent Authorial Input and Operational Mode of the Tattooist. In J. Martell & E. Larsen (Eds.), Tattooed Bodies: Theorizing Body Inscription Across Disciplines and Cultures (pp. 43–65). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86566-5_3

Sullivan, N. (2001). Tattooed Bodies: Subjectivity, Textuality, Ethics, and Pleasure. Praeger.

Sundberg, K., & Kjellman, U. (2018). The tattoo as a document. Journal of Documentation, 74(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-03-2017-0043

TTTism, & Schonberger, N. (2018). TTT: Tattoo: A Book by Sang Bleu (1st edition). Laurence King Publishing.

Featured image by Felix from Pixabay I The AutoEthnographer