An Autoethnographic Video Response to COVID-19: “Waiting for Elijah”

Artist’s Memo for An Autoethnographic Video Response to COVID-19: “Waiting for Elijah”

The holiday of Passover commemorates the exodus of the enslaved Israelites from Egypt. The holiday commences with a festive meal called a Seder-which in Hebrew means order, as the ritual meal follows a prescribed sequence of prayers, rituals, and blessings. Using a prayerbook specially prepared for the holiday meal, the Haggadah (“the telling”) takes those gathered around the table on a didactic journey from slavery to redemption.

The Passover Seder is not only a religious and sacred event. It is also an educational ritual that encourages questions, especially from the youngest members sitting around the table. The Seder is a time for families and friends to gather together with multiple generations sitting alongside each other and sharing the ancient story and the associated rituals. Through a series of experiential practices, it explains the story of Israelite enslavement and the exodus through the Red Sea. Near the end of the ritual meal, the door of the home opens in symbolic anticipation of the arrival of the prophet Elijah.

In the spring of 2020, COVID-19 caused the curtailment of Passover celebrations as the pandemic raged across the world. Instead of large multi-generation gatherings, we all attempted to stay safe, healthy, and COVID-free. Much to my dismay, I found myself in a similar situation a year later in 2021. One Passover separated from friends and loved ones was barely tolerable, but two were truly unbearable.

One Passover separated from friends and loved ones was barely tolerable, but two were truly unbearable.

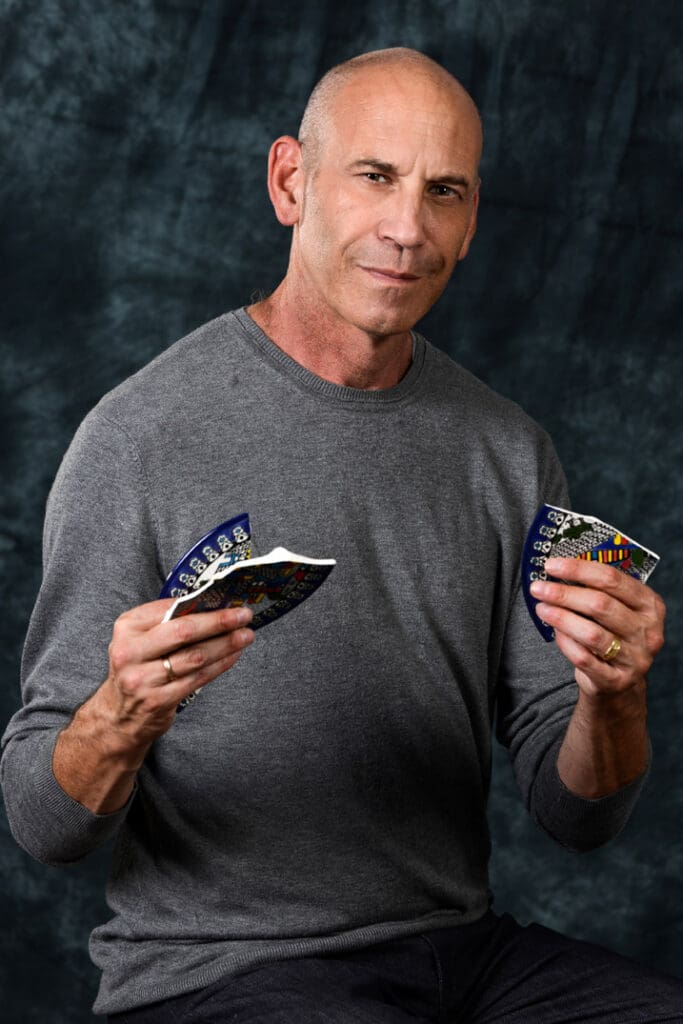

Since 2014, I have traveled through Europe and the United States sharing an autoethnographic performance entitled “Shards: Putting the Pieces Together.” This 75 minute original musical drama combines storytelling and song. It explores my experience of moving to Israel in the summer of 2013. The performed autoethnography is not only my story. I intertwine my narratives with tales of my grandparents’ immigration from Russia to Brooklyn at the beginning of the 20th century.

In the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic locked down the world and caused cancellations of multiple performances and artist-in-residence opportunities. In lieu of in-person performance, I reconceived the performance for an online audience. And in 2021, COVID again forced us to be in a lockdown situation. As such, I wrote a new version of the show (Shards: The Passover Edition). This online show featured the age-old Passover story recast for a pandemic age. The video performance utilizes autoethnographic narratives echoing the didactic steps of the seder and the themes of the ritual retelling.

The Passover Seder is not only a religious and sacred event. It is also an educational ritual in which questions are encouraged, especially from the youngest members sitting around the table.

As the Passover seder draws to a close, we open the front door of the home to symbolically invite in the prophet Elijah. The appearance of Elijah traditionally presages the arrival of personal or collective redemption. Thus, we open the door to the home and set aside a special goblet of wine for Elijah on the seder table serving. This is a symbol of welcome and hospitality.

When we open the door, we sing “Eliyahu HaNavi” (Elijah the Prophet):

Elijah the prophet,

Elijah from Tishbi,

Elijah of Gilad,.

May he soon (in our days) come to us,

With the messiah, descended from David.

Opening the door amplifies the theme of hospitality as presented in the Passover Haggadah in which the community is encouraged “to let all who are hungry come and eat.” During the COVID-19 years when having guests at the Passover table was discouraged, the axiomatic message of welcoming the stranger severely diminished. COVID-19 presented us with a terrible irony that forced us to reconsider the tradition of welcoming guests and strangers to our holiday table. Instead of open doors and physically embracing friends and family, we faced sealed doors. And the number of guests stayed limited to those in our COVID-19 bubbles.

COVID-19 presented us with a terrible irony that forced us to reconsider the tradition of welcoming guests and strangers to our holiday table.

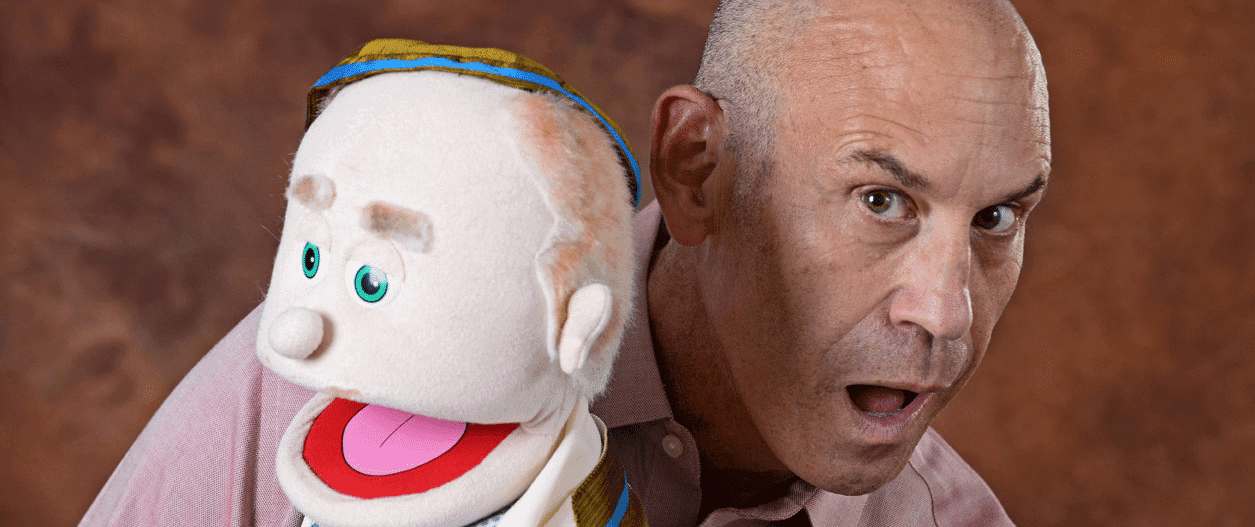

The following is an excerpt from the full-length video autoethnography “Shards: The Passover Edition”. It recontextualizes the song for the Passover prophet as a critique on his inability during the COVID-19 pandemic to appear and provide solace and safety. Using a musical motif adapted from the traditional folksong, I present the song as a personally perplexing and anguished moment in the seder, albeit filled with humor and a touch of sarcasm. The addition of surrealistic puppets, presented as blurry and out-of-focus video in homage to 1960s television images, enhances the bewilderment presented in the lyrics.

The lyrics (co-written with Jerusalem-based actress and theatre director Susan Berkson), express my personal disorientation at having to be at a socially-distanced seder once again. The lyrics reference to thematic and textual material in the Passover seder. But instead of extolling the prophet Elijah’s attributes, I interrogate and challenge the prophet. I chastise the prophet for failing to appear at other times during the course of history and question if all his attributes are real or perhaps fraudulent.

The lyrics (co-written with Jerusalem-based actress and theatre director Susan Berkson), express my personal disorientation at having to be at a socially-distanced seder once again.

Eliyahu eliyahu eliyahu hanavi

What’s the problem Eliyahu are you stranded in Tishbi?

So you didn’t get an invite, but we opened up the door

Set the table

Poured your wine cup

What the hell you waiting for?

How much kugel? How much brisket?

How much tzimmes? How much wine?

We’ve got more than four questions

And we’re running out of time.

We’ve been simple We’ve been wicked

We’ve been mute And we’ve been wise

And still you are a no show

Do you even hear our cries?

Next year in Jerusalem We’ve sung that for so long

It’s fifty-seven eighty-one There must be something wrong

Are you vegan vegetarian or maybe it’s the song?

Perhaps you’re social distancing or just a bit head strong?

Transfigure this: we need you now So kindly set your WAZE

For every seder table “Speedily in our days”

Since the start of history we’re crying out your name

A prophet who we never see- it’s always just the same

The table always ready and the door is just ajar

We’re ready and we’re waiting what the hell you waiting for

I’m getting just a little bored- my brother from Tishbi

Crying in the wilderness please set my people free

Maybe you’re invisible maybe you’re a fraud

But after so many years I gotta say “I’m bored”

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work? Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

I'm an auotethnographer living in Tel Aviv. My research interests are music and identity, community music, music acting as social intervention, and performance autoethnography. My autoethnographic original musical "Shards" chronicles the experience of my moving to Israel and my grandparents' immigration to the United States at the beginning of the 20th century.

I am interested in exploring the boundaries of autoethnography through song, poetry, video, and theatre.