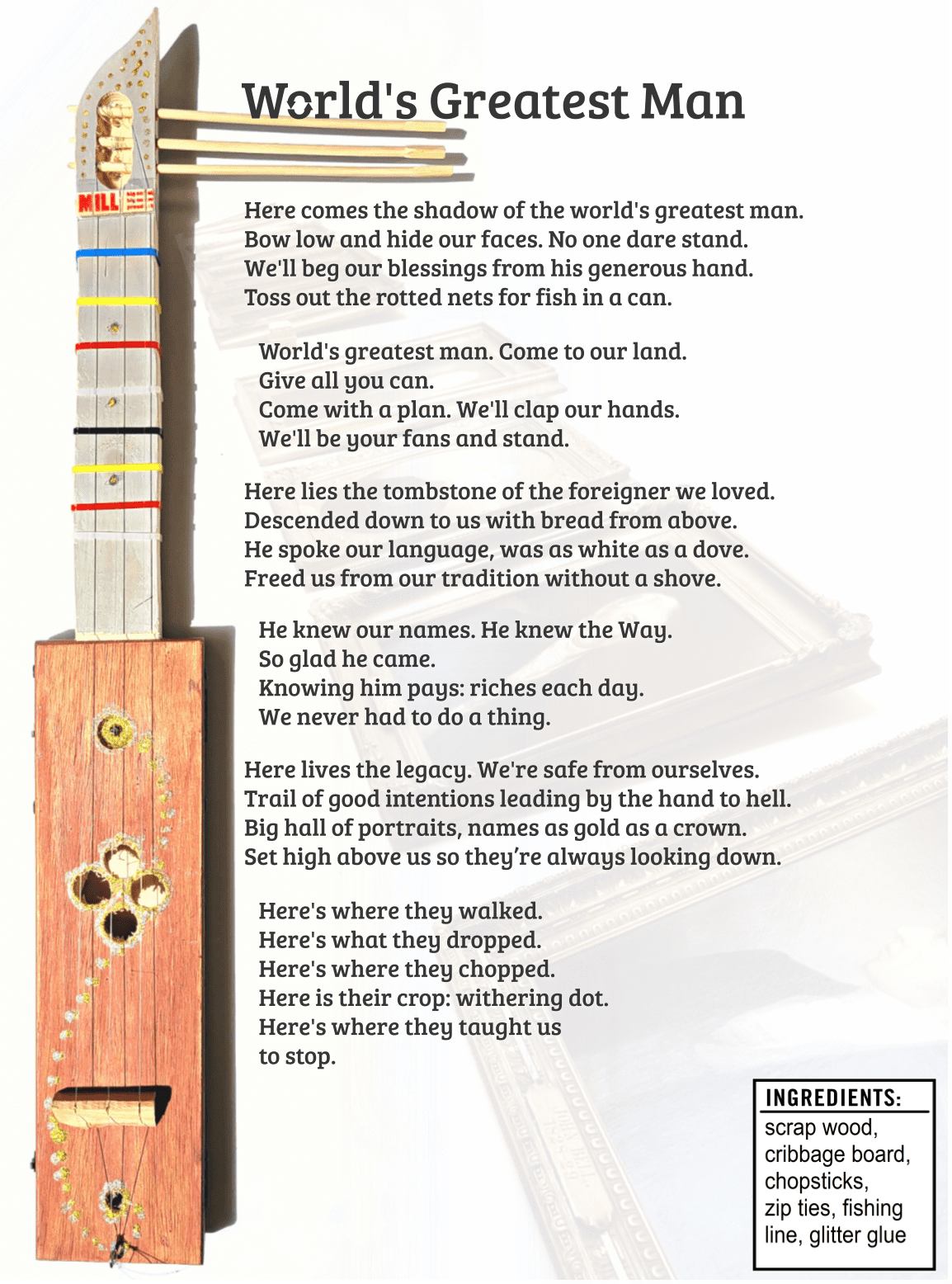

“World’s Greatest Man” Explores “Rice-Bowl Christianity” and Modernization in Thailand

Artist’s Memo

I served in the Peace Corps as a community organizer in northern Thailand. I then returned years later to conduct ethnomusicological fieldwork. In both instances, my real or assumed backgrounds affected my positionality and my conversations with members of the community.

Ethnographers before me were amazed if not alarmed by the quick pace of Karen conversion to Christianity and the ensuing sweeping changes to villages eager to modernize. I was interested in the co-occurring musical changes as these villages adopted and adapted new forms, instruments, and religious dogma.

Christian community members assumed a service-oriented American was missionary-affiliated and welcomed me on those grounds, in many cases to elevate themselves. Traditional Karen legends had long ago foretold of a “white brother with a golden book” before the arrival of western missionaries. This partnership and presence is still celebrated today. In our conversations about religion, I was thus viewed as colleague. When our conversation topic shifted to music, I became the perceived authority. My questions on culture quickly categorized me as novice and foreigner.

‘Ethnographers before me were amazed if not alarmed by the quick pace of Karen conversion to Christianity.

Buddhist politicians also welcomed me on stage for photo opportunities. It seemed that my mere presence elevated their cache amongst their constituents and promoted their development projects. My American face, if none of my other attempted collaborative work, was prominently featured in their annual reports.

The lyrics of “World’s Greatest Man” grapple with the paradoxes of participant-observation as well as the ambiguity of development work in Thailand. Big names and foreign faces are needed to bring attention. But altruism, honesty, and appreciation are maddeningly difficult to assess within a culture that highly values communal face-saving, deference, and performative charity. Ethnographers observed and coined a term for “rice-bowl-Christians.” These were highland communities who, whether out of cunning agency or genuine religious fervor, adopted Christianity en masse in the 1960s-80s and enjoyed the subsequent social uplift it afforded. Perhaps their faith was genuine. Perhaps not. Did that really matter? Do the ends justify the means? And which are ‘the ends’ and which are ‘the means’ anyway?

The lyrics of “World’s Greatest Man” grapple with the paradoxes of participant-observation as well as the ambiguity of development work in Thailand.

“World’s Greatest Man” is written from a first-person (auto-ethnographic) perspective. From this vantage point, we can’t tell if the narrator’s tone is a genuine admiration of animistic rituals’ hardships abandoned, a sarcastic observation of rice-bowl opportunism, or a lament over decimated indigenous lifeways. The auto-ethnographic narrator (real or fictionalized) takes no position as to whether community members should hold any of these perspectives. Rather, we invite the listener to observe and sit with that ambiguity.

About the Artist

Benjamin Fairfield received his MA and PhD in ethnomusicology from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he serves as lecturer and founder of the MUS311 Thai Ensemble (a sustainability-focused course where students repurpose found objects into Thai musical instruments). He also taught music at Ala Wai Elementary School, produced a high school garage band rock album in Thailand as a Peace Corps volunteer, and has published various academic articles on music in Ethnomusicology, The Malaysian Journal of Music, Asian Music, and Ethnomusicology Review. His trash-turned-instruments can be seen and heard on instagram (#MUS311), and more information, tutorials, and videos related to his Kani Ka ʻōpala project (building musical instruments from found rubbish) can be accessed at his website, www.kanikaopala.com.

Credits

Featured Image provided by Benjamin Fairfield

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Benjamin Fairfield received his MA and PhD in ethnomusicology from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he serves as lecturer and founder of the MUS311 Thai Ensemble (a sustainability-focused course where students repurpose found objects into Thai musical instruments). He also taught music at Ala Wai Elementary School, produced a high school garage band rock album in Thailand as a Peace Corps volunteer, and has published various academic articles on music in Ethnomusicology, The Malaysian Journal of Music, Asian Music, and Ethnomusicology Review. His trash-turned-instruments can be seen and heard on instagram (#MUS311) and the full album Kani Ka ʻōpala (recorded using only his home-made junk instruments) can be heard on various streaming platforms, including YouTube.