A Poet Investigates Privilege During Life in Nigeria

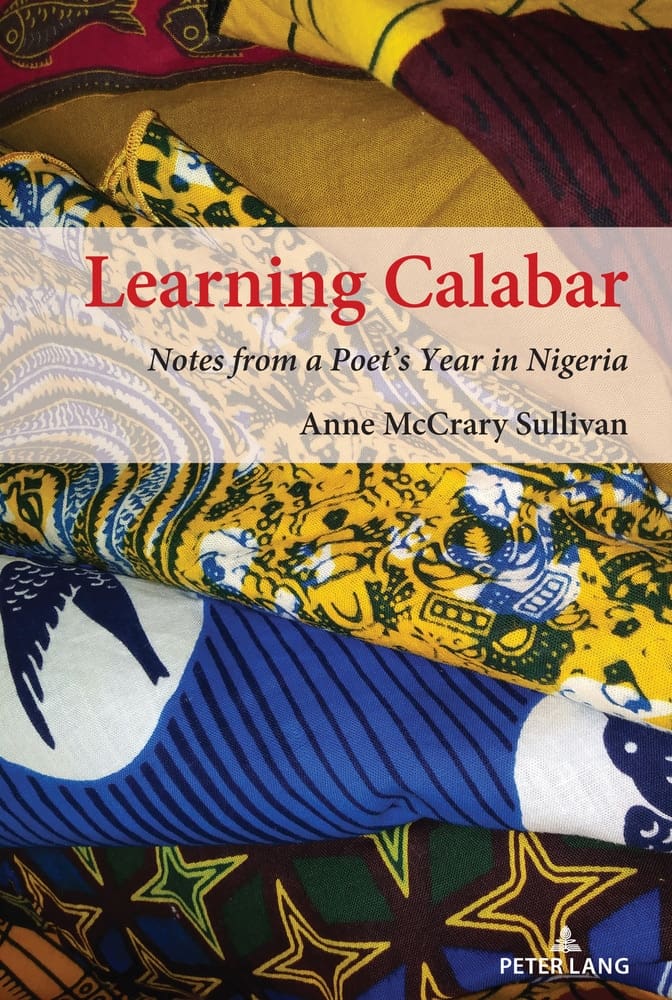

Our editor Dr. Michelle Reale is interviewing poet Anne McCrary Sullivan about her autoethnographic poetry and more specifically about her latest book Learning Calabar, Notes from a Poet’s Year in Nigeria which is a wonderful example of the intersection of culture, autoethnography and poetry.

MICHELLE REALE: You are a prolific and deep poet—your words connect with nature itself and your interactions with the natural world. Tell us when your abiding connection to nature began.

ANNE MCRARY SULLIVAN: There’s a story my mother told, not many times, but I have remembered. I was very small, a babe in arms. We lived in a remote area, on bluff that overlooked a water wilderness, marshes and channels as far as we could see. On land we were surrounded by oaks, hickories, and scrub. In the story she told, she went out, carrying me, to stand among trees at the top of the bluff, looking over the marshes, watching a storm come in. She held me close, and she said she felt me settle in the roar of wind, my eyes wide, “rapt” in the sounds of storm. “I knew then,” she said, “that we would share a love of this.”

I like to think that was the beginning of my abiding connection to nature. Sometimes I think about how important it was that I felt warm and safe in my mother’s arms during storm. I have always loved storms. Thunder comforts me.

I have written a lot about my mother’s influence on my life. She loved the world deeply. Growing up in her company, in boats and on mudflats, in forests and in bogs, I learned to love the world deeply, too.

MR: How would you describe your poetic sensibilities?

AMS: You know, I’m not really inclined to do that. To describe my poetic sensibilities is to somehow lift myself out of them, detach in a way that I do not love. But the question raises an issue that I have been thinking about for a long time in relation to arts-based research. It’s a matter of the tension between making art and critiquing/analyzing art. Generally speaking, artists of whatever medium do not go around analyzing their own work. Artists make art. Critics analyze, explore, tease out implications, describe artistic sensibilities.

I’ve observed a lot of progress in the emergent field of arts-based research in the last couple of decades, but this is something I don’t think we have worked out yet. Because of the structure and demands of the academy, it’s not easy. But I think there are ways we might satisfy the not un-worthy analytical demands of the academy while honoring the distinct roles of artist and critic.

We can, for example, play the role of art critic for each other. I can write a poem, and you can write about it. You can write a poem, and I can write about it. I would love to see an edited volume based on that kind of exchange, the work itself paired with a work of analysis by someone else, writers and critics swapping roles. In that way, artist-researcher-academics have the opportunity to demonstrate analytical and theoretical skills without having those operations intrude on the art-making itself. Meanwhile, in the academy, artists are often expected to accompany their own work with lit review and analysis. In some cases, I do think this works comfortably for the artist. I just think we need more than one way to go about this.

MR: Your latest book Learning Calabar, Notes from a Poet’s Year in Nigeria is a wonderful example of the intersection of culture, autoethnography and poetry. How did you come to commit one year in Nigeria as a nexus for this important work?

AMS: Like so many wonderful things, my year in Nigeria was a matter of unexpected emergence. I had had a long affection for the continent of Africa, its landscapes and its people. I had been in a half dozen different African countries for short periods of time, mostly for academic reasons. But, I had never been in Nigeria.

When I was attending a literacy conference in Ghana, I met a woman who, prior to the conference, had never heard of qualitative research, wanted to learn. Long story short, I applied for a Fulbright and went to Nigeria to teach (among other things) qualitative research methods. The word Learning in the title of the book is important. I knew almost nothing of Nigeria before I started a reading frenzy when I knew that I would actually be going. One can learn a lot from reading, but my real learning came from living there, interacting with neighbors, children, colleagues, market people. Some of that learning was hard. But I can no longer imagine my life without Nigeria in it. I love and miss many of the people I left there. The book is about my personal and cultural learning in a context that challenged and humbled me.

I think there are ways we might satisfy the not un-worthy analytical demands of the academy while honoring the distinct roles of artist and critic. We can, for example, play the role of art critic for each other. I can write a poem, and you can write about it. You can write a poem, and I can write about it. I would love to see an edited volume based on that kind of exchange, the work itself paired with a work of analysis by someone else, writers and critics swapping roles. In that way, artist-researcher-academics have the opportunity to demonstrate analytical and theoretical skills without having those operations intrude on the art-making itself.

MR: How did the format for Learning Calabar come about? How is this a departure from traditional scholarship?

AMS: The book consists of alternating chapters of poetry and prose. This was not something I planned in a linear, conscious way; it was what the story asked for. And in a way, it mirrored my journals of the time, sometimes poetry, sometimes prose. It seemed that some things were best said poetically, while others demanded prose. And it’s a rather recursive book, sometimes telling the same thing in more than one way.

This book departs from traditional scholarship in a couple of ways, and these relate to the artist-critic issue I was talking about. In the first chapter, I make a few nods towards the literature. After that, there are no references at all. But I do make extensive use of end notes in which content is filled out and academic resources provided. The notes contain material that would have interrupted the artistic expression of the main part of the book. So I guess you could say that I was trying to find one way to meet both artistic and academic demand. Often the artistic becomes subservient to the academic. I wanted to turn that around.

In the early days of arts-based research, I often heard in discussions at AERA a desire to break down the barriers between academic research and a public readership. If we are to do that, we have to create work that is accessible to a world beyond the walls of the academy, un- encumbered by a visible academic apparatus that alienates readers outside that academy. I wanted Learning Calabar to be that kind of work.

MR: Describe for us the particular autoethnographic aspects of this work in particular and other projects you have worked on.

AMS: Learning Calabar plays out at intersections of the personal and cultural, the historic and the now, the artistic and the academic. For me, this defines the autoethnographic realm. I think pretty much everything I do plays out in this domain. I don’t know how to see the world “objectively.” Or maybe I just don’t want to. With seeming infinite curiosity, I choose to see and explore both cultural and natural worlds with the instruments of my own being and knowing, not excluding other scholarship, but building on it in ways that only I can, because it is personal. Autoethnography is the landscape in which I live. As with other landscapes, I love its variety, its surprise, its underlying social ecologies.

MR: In Learning Calabar, you acknowledge your privilege. Can you explain why this admission is an important aspect of the work?

AMS: I can’t imagine doing this work without that acknowledgement. Part of the learning in Learning Calabar is specifically about the depth of that privilege and how easy it is to take elements of privilege for granted—even among those of us who are intellectually aware of it. Over and over again in Calabar, my sense of my own unearned privilege was made visceral, and I had to decide what to do about it. Privilege is insidious. Becoming intellectually aware is only a beginning. That’s part of what I learned.

MR: In the book you write that you began to wear the traditional Nigerian dresses. Did wearing those dresses help you to embody the learning you sought to do?

AMS: I don’ know. If so, I wasn’t aware of it in that way. At first, I resisted wearing the dresses because my training had taught me that I had no right to wear them; to wear them would be appropriation. It wasn’t until I was invited to wear them (“Prof! You need to dress Nigerian!) that I adopted the habit.

As I think of it now, prompted by your question, I think that wearing the dresses gave me a new kind of privilege, an invited privilege that felt like acceptance, a welcoming into a culture where I was clearly an outsider. In some way, perhaps that helped me to deal with the unearned privilege I had dragged across the ocean with me. Perhaps I had in some way earned this privilege. At any rate, I loved those dresses, their wonderful patterns and colors and ruffles, the sense of somehow belonging in Calabar that they gave me. I had a dress of each of the fabrics that appears on the front of Learning Calabar. But the privilege of wearing those dresses is a privilege I left in Calabar. To wear them here would be a whole different matter. I haven’t earned that right here. I haven’t been invited.

This book departs from traditional scholarship in a couple of ways… In the first chapter, I make a few nods towards the literature. After that, there are no references at all. But I do make extensive use of end notes in which content is filled out and academic resources provided… So I guess you could say that I was trying to find one way to meet both artistic and academic demand.

MR: Because habit and practice are essential to the writer / poet, can you describe yours?

AMS: I write every day. It’s obsessive. I don’t wait until I have something to say. And I write an incredible amount of junk. I long ago gave myself permission to write junk. It’s part of keeping the writing reflex alive and nimble, part of learning to hear myself think and to translate that thinking to the page. I write and write and suddenly I discover that I have something to say. I don’t hesitate then or think I need to write about that; I just keep writing.

And I used to tell my high school students, in that first teaching life of mine, “Go fishing in the stream of consciousness. Maybe something will bite.” It’s advice I take myself. I go fishing all the time. Sometimes I catch something. Even when I don’t, I’m having fun. And you never can tell where that stream will take you. You can start out with hurting feet and end up with an insight into a philosophic problem.

I write early, before the sun is up, before the world’s business begins. And then I write off and on all day. I always have a journal with me. Writing is what I do. Writing by hand slows me down, and sometimes that’s a good thing—good for contemplating, for dwelling in something. But if thinking is moving hot and fast, I go to the computer.

MR: Use five words to describe your experience in Nigeria.

AMS: difficult; deep; loving; humbling; transformative.

MR: What comes next in terms of your writing and travel?

AMS: Right now I’m on the Big Island of Hawaii for five weeks. I’m revising (yet again) a manuscript that could be called memoir, could be called autoethnography, depending on who you’re talking to. It’s the story of my brother who lived on this island for almost twenty years. Rather, it’s the sister’s story of how she learned to see her brother as more than his alcoholism, how after years of estrangement she found a way back to him and learned to love him fiercely before he died. It’s a book that raises a lot of social issues.

When I return to Florida, I will resume work on Gladeswoman, working title of a personal, natural and social history of the mangrove wilderness of the western Everglades.

Along the way, I’m trying to construct a coherent manuscript from an unruly pile of poems.

And there are other projects at various stages of development. I always have more than one thing going at a time. If I’m working on something and get stuck, I switch to something else for a while. Working that way, it sometimes takes me a long time to finish anything, but when I take the long view, it seems efficient. Little by little, the work gets done.

Photos from Anne McCrary Sullivan I The AutoEthnographer

Featured photo of Lagos Nigeria by Idowu Emmanuel from Unsplash I The AutoEthnographer