Autoethnographic Essay: The Unbearable Triteness of Being (Middle Class)

Author’s Memo

My own work, such as this autoethnographic essay, grounds itself in practices of narrative inquiry. My most recent book, On Drugs, bases reflections on medicine, academic philosophy, alcoholism, and obsession in the lived experience of addiction and work. The current essay explores in a (hopefully) creative way ideas about social class in relation to my own negotiations of identity and upbringing in eastern Sydney, Australia.

Had there been an internet I might have also been able to check something else out, a strange belief of mine: that my family was poor, even embarrassingly so. My dad, who seemed old compared to other people’s dads, didn’t appear to work much; I thought he might even be unemployed. I would have asked, but I didn’t want to embarrass him. He also seemed to wear the same clothes every day; and he often walked around only in shorts. Sometimes, I couldn’t tell whether they were underpants or shorts. Sometimes, I’d walk into his room and he’d be standing on his head, a yoga pose, in underpants. It didn’t really seem to me like what an employed person might do.

Autoethnographic Essay: The Unbearable Triteness of Being (Middle Class)

Until pretty recently I pronounced ‘awry’ as ‘orry’. (It’s‘ah- rye’.) And I thought that refrigerators worked by blowing cold air onto food. The further I go back in time the more arresting and idiosyncratic the errors get. I thought that when I turned twelve I was going to get my period — that blood would jet from my penis; I thought that babies emerged like the Northern Lights out of women’s anuses; that sex was just a rumour started by Julian A in Year Three; that my schoolteachers all lived together in a big house; that the Village People were heterosexual; that everyone who wore sunglasses was blind; that the Beatles were from Liverpool, Sydney; that Bill Posters was a fugitive; that a lead guitarist’s lead guitar was made of lead.

I’m unsure how atypical these sorts of misconceptions are, how outside the plot of the bell curve they sit. It can certainly be illuminating to have a long, dry conversation with a five-year-old should one want to refamiliarise oneself with what ordinary insanity looks like; an object lesson in how readily one can get along in the world while holding the views of the deranged. It’s not just children, of course. That between twelve and fifteen million Americans believe the world is controlled by alien lizards doesn’t entail those same people can’t put their socks on under their shoes, remember the words to Happy Birthday, or put petrol in their cars. The fact is, all of us can get along quite well in the world believing in absurdities. We may or may not be reassured that there are good philosophical reasons for this.

Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein, in Philosophical Investigations, asks us to imagine a builder and their assistant who interact in a basic language consisting of just the words ‘block’, ‘pillar’, ‘slab’, and ‘beam’. The builder calls out one of these words and the assistant throws the builder an object. Watching this, we’d be likely to conclude that each of these words names an object and an imperative to throw it: ‘block’, and they are thrown a block; ‘slab’, and they are thrown a ‘slab’, and so on. But there is, in fact, no logically compelling reason to be assured that this is actually what’s going on. A number of alternative possibilities exist; the builders may, for instance, be speaking another language where equivalences like this may hold:

- » block = thanks

- » pillar = next

- » slab = ready

- » beam = okay

Because of this, an onlooker may be able to watch what was going on without ever knowing what was, in fact, going on. And it may not just be an onlooker who misunderstands — the builders may themselves be using different languages and no problem will emerge unless their behaviours clash in some way. The first builder might be using the above language; the assistant might be using this:

- » block = throw

- » pillar = is that all you’ve got? Harder, you fool!

- » slab = you’re weak!

- » beam = good one!

And the building might still get built.

The child, in particular, can get along perfectly well in the world without really understanding a lot about it. I remember having a vaguely coherent exchange of opinions about ‘youth in Asia’ (my rendering of ‘euthanasia’) as a child. I didn’t quite know ‘what all the fuss was about’, I said, shocking my primary school teacher interlocutor. I was, ‘at base, ambivalent’ about the issue. This seemed to be an authoritative and rightly skeptical position to hold, at least according to my incomprehension as to why youth-in-Australia weren’t of equal concern to people, why citizens’ views about them weren’t being sought on Geoffrey Robertson’s Hypotheticals. ‘Ambivalent isn’t even a word; you’ve made it up,’ a friend told me. I replied that it was in a John Farnham song. Thank god there was no internet back then; I might have lost that argument.

My family was poor

Had there been an internet I might have also been able to check something else out, a strange belief of mine: that my family was poor, even embarrassingly so. My dad, who seemed old compared to other people’s dads, didn’t appear to work much; I thought he might even be unemployed. I would have asked, but I didn’t want to embarrass him. He also seemed to wear the same clothes every day; and he often walked around only in shorts. Sometimes, I couldn’t tell whether they were underpants or shorts. Sometimes, I’d walk into his room and he’d be standing on his head, a yoga pose, in underpants. It didn’t really seem to me like what an employed person might do.

And we lived in an old house, possibly haunted, I thought (rich people could afford unhaunted houses), with stairs that creaked and worn-down carpet. In primary school, I’d be embarrassed to bring friends over. People would sometimes remark on how big my house was, but to my child mind, size didn’t signify wealth. (Diamonds were here the relevant object lesson — why wouldn’t the principle hold in other areas?) And my best friend, JJ, lived in a block of units with a pool and an intercom you had to buzz to get let in. This seemed incredible to me, like something from The Jetsons. An intercom.

More evidence: save underpants and socks, my clothes were almost always hand-me-downs from older brothers and sisters. My pleas for fancy new shoes were never heeded: ‘Your feet are growing too fast to waste money on proper shoes!’ my mother would say. The other kids at school wore Nikes and Adidas; I wore Dunlop or, more embarrassingly still, Grosby or Lightfoot sneakers. And if an older brother’s shoes were well-preserved, I’d get them. I hated the feel of the misshapen sole which had customised itself around a sibling’s foot. And, speaking of this, why on earth did I have three brothers and three sisters? Was this why we were poor, or simply another sign of it? Whether causation or correlation, it was further confirmation. Nobody I knew — perhaps besides the Sullivans in Pauling Avenue — had so many people in one house. It was like my family had been dropped into the twentieth century from an earlier, poorer age. We almost never ate out; there were no lollies or chocolates in the fridge. I assumed ‘junk food’ must be expensive: it tasted better than everything else; it must be very pricey, I reasoned, otherwise adults — who had nobody telling them to eat their lettuce, and other wild grasses — would be eating it all the time.

‘Jam them!’

I did eat fast food, though, albeit in particular circumstances. My mum worked as a ‘market researcher’: we got free meals at places like Red Rooster and KFC by posing as customers. (My mother refused to allow me to wear the fake moustache I got in one of my Easter Show showbags, which I thought would help our cause.) We’d order our food (exactly as prescribed by the market research company) and then return to the car to fill out a report rating the service personnel. Mum would then pull out a hard plastic case containing the exciting special equipment: a Comark Digital Thermometer ‘with Surface Probe’. The chicken would be pierced with the probe and its temperature read. Mum would note this down in her log. I knew other people didn’t do this — none of my friends, anyway. After the report was done, we could eat, sitting in the car in the restaurant carpark. Why couldn’t we just go to KFC and buy the food? This was the only way I got this kind of meal.

Once Mum didn’t quite break her cover, but she did let it be known that the service wasn’t good enough. At one point, McDonald’s were giving away a sleek Paper Mate Kilometrico ballpoint pen (I note, currently available at Officeworks at $3.50 for a box of ten) with all Big Mac orders — but when we went to the car, there was no free pen. ‘Jam them!’ my mother huffed (her odd method of cursing will be covered in due course) and re- entered the restaurant. ‘Where’s our pen?!? We bought a Big Mac just a moment ago and there’s no jam pen!’ I’d rarely seen her in this kind of rage. It was amazing, and incomprehensibly embarrassing.

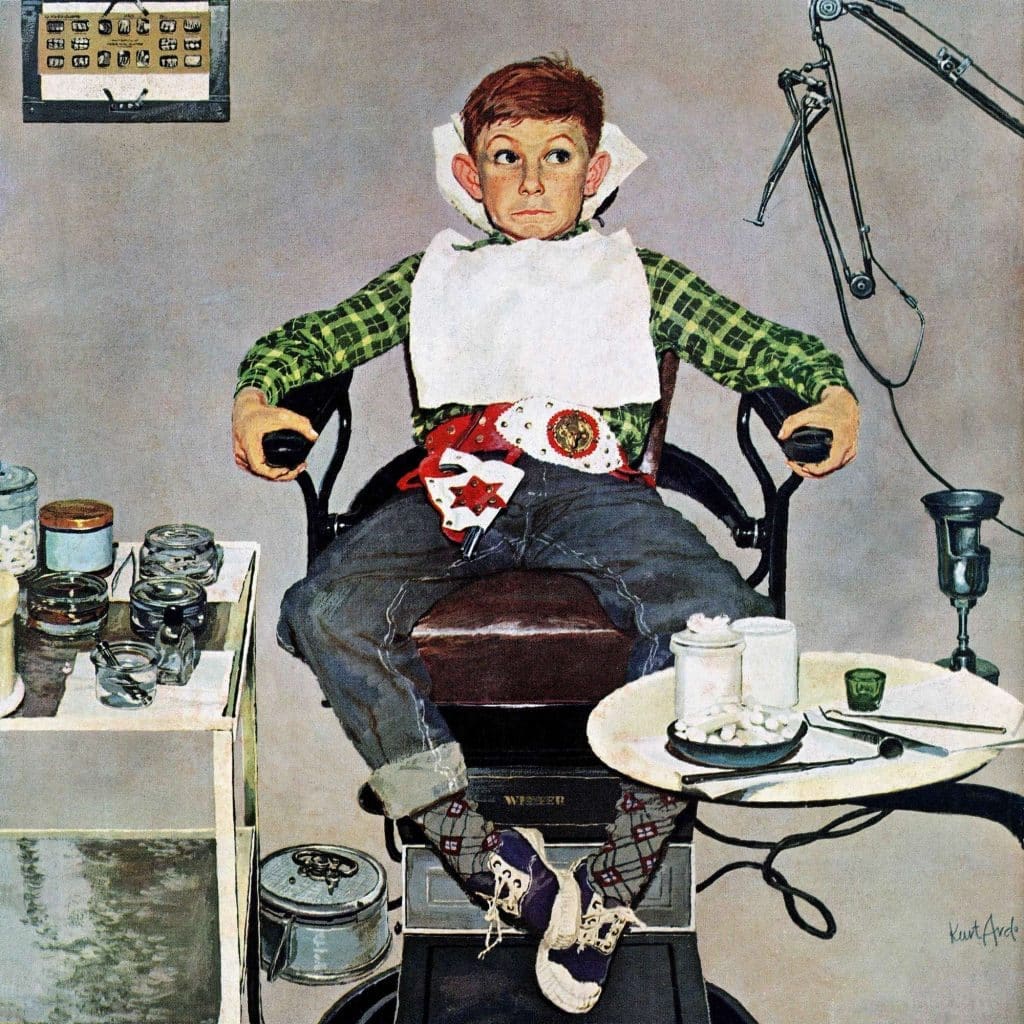

False teeth were much more convenient

Maybe we didn’t eat fast food — especially lollies — because going to the dentist was expensive, I thought. The early years of my life had gone by and I’d not gone to the dentist at all. My friends, on the other hand, seemed to be going all the time. I really thought that my first visit was going to be like a visit to the barber, if not with respect to mechanics then apropos pain levels. I remember watching a Sesame Street episode where a baby bear is terrified about going to the barber because he thinks it’s going to hurt. His fear had seemed absurd to me; it even made me feel like I’d outgrown the show: I’d never been afraid of getting a haircut. Given the huge number of fears I had at the time, an almost limitless number of fears, it was some comfort to realise that this was one fear others had but I didn’t.

I remember being excited by the prospect of the dentist; it seemed like quite a grown-up thing to do, and had something, I knew, to do with science. So, I prompted my parents, on the off chance we could afford it. To my surprise, my mother obliged. My mother really didn’t have much personal experience with teeth as she’d had them all removed in her twenties. (Until the 1960s there was a school of thought that believed having teeth was just too much trouble; false teeth were much more convenient — you could just pull them out of your mouth and clean them.)

My mother escorted me into Dr H’s office: first, into the waiting room, where there was a chair, desk, and phone for a secretary but no secretary. I noticed that the phone was no longer connected to the wall, and the desk was thick with dust. I began to wonder if dentistry wasn’t a high-earning profession after all. Dr H, who had shown a cheery demeanour in the presence of my now absent mother, made me sit in the seat. His smile had vanished as soon as my mother had — the kind of horror-movie shift where the protector leaves and, with evil countenance, the villain says, ‘It’s just you and me now …’ A pale-blue light filled the room, vaguely hallucinogenic, like we were underwater. Dr H was not of today’s generation of dentists, neither in temperament nor training. He made no attempt to smile or act human. I was a little child-object, and he was a mechanic or engineer trained to look for breakage or malfunction. These days, such an approach suits me perfectly well; I have become tired of dentists looking into my mouth and showing disappointment — like I’ve let them down somehow, that I cause them grief. But at the time it was terrifying and alien: the strangeness of having him reach into my mouth with metal objects and start scraping at my teeth like he was engraving something. This was nothing like getting my hair cut.

When he saw two holes that needed filling, I started to panic. ‘Tsktsktsk. Not much of a brusher, are we?’ He seemed energised — even gleeful — about my dental neglect. ‘Oh well,’ he said, smiling for the first and only time. He went into his back room and returned carrying a needle in front of him like some sacred harpoon. I was utterly stunned by the pain and strangeness of the thing piercing the soft tissue at the back of my lower gum. And then the phone rang. Dr H left the room and I heard him chatting and laughing. The laughing began to seem sinister.

And the call went on — and on and on and on. He laughed and recounted stories and swore and behaved like no adult I’d ever heard. It was the first time I’d heard the phrase ‘complete deadshit’. I was starting to think he was a rogue practitioner; possibly even an illegal one, offering sham services to those who couldn’t afford proper dentists. He was gone for a long time — I knew he’d forgotten about me, lying there with a silver javelin hanging out of my mouth. I started to cry quietly. I knew if I moved too much the javelin would fall out and he’d need to put it back in again. And then I heard it: ‘Oh fuck! Sorry. I’ve got a patient.’ He put the phone down and he hurried back into the room. ‘You thought I’d forgotten about you, didn’t you?’ he asked jovially. ‘Uh-uh,’ I replied, lying. ‘Okay, stop crying,’ he said simply.

I was astonished at how horrific the whole experience had been, that people actually went through things like that. Maybe growing up itself at least partly comprises asking that exact question repeatedly in different circumstances: how do adults endure this sort of stuff? There was no doubt in my mind, now: he was a budget dentist, a bargain-basement quack. There was no other explanation. We couldn’t afford a real dentist. More evidence! Maybe it was even free. This seemed to be confirmed when the filling began to hurt. He’d not drilled adequately, so that one tooth began to rot under the filling until eventually part of it broke off and just slid away, allowing saliva into a ravaged half-molar and a hysterical nerve. I didn’t tell my parents. I told myself that I was saving them money; the real reason was naked terror. I was never going to a dentist again, even if I got rich.

Whose grandad is driving the Jag?

But like many things radically inconsistent with reality, my illusions about my family’s poverty were eventually punctured. It happened at school camp at the end of Year Eight, when my father drove the family car into the campground carpark to collect me. Boys were gathered at cabin windows, looking out:

‘Whoa! Whose grandad is driving the Jag?’ ‘Cool!’

‘My god! Cool car!’

‘Whose Jag is that?’

More kids gathered around. I didn’t want to admit that it was our car — not because I yet understood our car implied wealth, but because of my ongoing embarrassment about my elderly father. Eventually, I muttered a meek, ‘It’s ours.’ ‘Bullshit, Fleming,’ a fellow student said, for reasons I still don’t understand. And then the questions: ‘Are you rich?’ and ‘Is your grandpa rich?’ My answer was one that strikes me now as entirely consistent with what a future philosopher might give: ‘I don’t know. What is being “rich”?’

Being seen as rich was not a problem at my school or in my peer group — only so long as it didn’t entail being ‘spoiled’. For instance, a kid in my year, who lived in Sylvania Waters, got two real arcade-game machines for his birthday; people quietly criticised that. Being rich wasn’t exactly admired, but it wasn’t looked down upon as it would be at university, where being rich was equated with ‘privilege’, and having privilege was somehow indistinguishable from being a bad person.

Wealthy? Hm. I don’t know.

Stubbornly incorrect, I still couldn’t figure it out — why did my poor family own a rich family’s car? Was my dad into cars? Is that where he spent all our money?!? So, I asked my father, who gave me an answer (befitting the father of a future philosopher): ‘Wealthy? Hm. I don’t know. What exactly is “wealthy”? Maybe we are, to some extent. Let me think about that.’ It wasn’t just an evasion — perhaps a way of stalling my purchase requests if the answer was ‘yes’. I think my dad was actually thinking about it carefully; he tended to do that, regardless of the question. But the question here isn’t a straightforward one. Where ‘wealth’ is something economics and the social sciences are very happy to define, ‘wealthy’ is far harder to grasp in any ‘scientific’ sense. Of course, this is not to say that we don’t do it — we can use ABS figures to calculate a household’s assets and define the top quintile as wealthy. But being wealthy corresponds to no set trans-historical material condition: it is always a relative measure, relative to what others own, of which a subjective element is irreducible.

Of course, one can ask: what of it? At one level, surely none of the above definitional demurral or equivocating matters. Like being white, knowing how to pronounce ‘awry’, or being six feet tall, wealth confers advantages — real, tangible, material advantages — whether we’re aware of them or not. Relative, mutable advantage is still advantage. It’s like the scenario of two men suddenly facing a tiger: ‘How fast can you run?’ one asks the other. ‘About twenty kilometres an hour.’ ‘There’s no chance that’s fast enough to outrun a tiger,’ says the first. ‘True,’ replies the second. ‘But I don’t have to outrun the tiger, I only have to outrun you.’ And the advantages of relative wealth, via those material tangibilities, is entry into a strata of class.

The fact is, I grew up in Coogee, went to a private school, was the son of a banker. But class is more than this — its advantages extend out beyond Jaguars and bank balances. The classical Marxist idea of class is tied literally to wealth, but this is usually considered a too- blunt instrument these days to account for a variety of social stratifications we’d still want to associate with the idea of class. It is admittedly rare these days for the English upper class to continue that elective speech defect of the gentry — the rhoticism — although we’ve known, at least since the work of American linguist William Labov, that class is perpetuated by sound and syntax as well as stocks and bonds. The stigmata of class are maintained through the operations of culture — the way people speak and what they name their children, what newspapers they believe, about whether they read newspapers, about what constitutes reasonable ambition, and in whose company one feels at home.

Shoeless

I had all of the advantages, via our relative wealth, of being middle class without being aware of them; that’s one of the main ways in which class continues to function: it confers advantages even most effectively without people being conscious of having those advantages conferred. The meritocratic ideal, although sometimes handy at the level of personal motivation, is dreadful when converted into a social theory. That people believe their achievements are correlated mainly — or even solely — with their own intelligence and work ethic relies on the idea that ‘structural’ factors, like race, class, gender, and ethnicity, are somehow negated, rendered effete by an ostensibly egalitarian social structure. We know — and have for some time — that, contrarily, class impacts very dramatically on things like health, educational attainment, on political influence, employment prospects, and on people’s experience (or lack of it) with the police and judiciary.

That my mother arrived into the middle class was a matter of the advantages bestowed on marrying my father. Her pre-married life had been one of crippling poverty. Poor enough to go to school shoeless, her uniform made from salvaged curtains, she was keen to never land back in that position. Her father was an alcoholic and drug addict, and spent a large part of his latter life homeless in Centennial Park; my mother would pass him on her way home from school and could never predict whether he’d recognise her. She was unable to take up a scholarship in veterinary science at Sydney University, instead having to go to work straight from school as a secretary to support her family. (There are undeniable injustices related to gender here as well: a brother of hers — with far less ability — was not required to carry the same financial burden, and was able to pursue a career he found meaningful.)

An ‘a’ like that in cart and fart

I’ve increasingly wondered about the designation ‘materialistic’ to describe the pursuit of wealth. It seems to me that those most interested in material acquisition are the poorest in society; there is nobody more ‘materialistic’ than someone who is hungry. The wealthy, however — having their material needs catered for — tend to pursue altogether more immaterial pleasures — prestige, status, some imaginary medal in The Great Scheme of Things. The wristwatch is undoubtedly a piece of matter — but ‘Rolex’ is pure signifier. The measure of class, therefore, can’t ever quite be captured simply in terms of the pursuit or weight of coinage. It travels, is marked out, in different ways. I remember my mother showing me the film adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion — My Fair Lady — as a child, perhaps to impress on me the importance of … like talking proper and all that. She winced at what she saw as mispronunciations and misuses of English, reserving perhaps her greatest antipathy, for some reason, for the word ‘brang’. She pronounced dance as da ns, and not the typical Australian dæ ns — that is, with an ‘a’ like that in cart and fart and not like in cat or hat. (More outrageously, she sounded plant the same way — and, parenthetically, would never have used ‘fart’ as an example.) She also never cursed, even using ‘jam’ and ‘plaster’ in the place of ‘damn’ and ‘blast her!’ I’d once heard her say ‘Oh bucket! Buck him! What a muddy basket!’, the recodings of which might make a delicate sailor blush.

But she came to live, later in life, through another transition of cultural meaning in relation to wealth — one in which certain kinds of hardship slowly began to be romanticised — and I’m not simply talking about the ratings for Australian Story. The convict ancestry of my family, assiduously kept from view while growing up, suddenly became a point of pride in the 1990s — perhaps not for its intrinsic worthiness, but by virtue of a sense of ‘look how far we’ve come!’ What is striking now, though, is the phenomenon of the studious unfairing of ladies, of what might be called Noilamgyping, of reverse Pygmalion-ing: of the privileged adopting the speech and dress of the great unwashed, of boys from Cranebrook at Sydney University doing Eshay-lite, of the phenomenon of recreational slumming, of saying you grew up two suburbs west of where you did, of talking less like someone in a play by Oscar Wilde and more like one by Alex Buzo. One can understand the appeal, even if the results are both ethically dubious and cringeworthy.

I accept I’m a bogan

Today, my students, many of them the first in their families to go to university, want desperately to be middle class; but the one thing the Literary Writer doesn’t want to be these days is middle class. Of course, not wanting to be middle class is yet another privileged aspiration of certain sections of the middle class. (If being middle class is a kind of oppression, it’s perhaps on par with having butterflies thrown at you.) Being middle class these days remains a huge advantage, but this doesn’t stop it from being desperately uncool; it’s the infinite distance between Coldplay and Pulp, the chasm separating The Streets’ Mike Skinner saying ‘bruv’ and David Cameron saying it. And people realise this.

In a move that seems consummately contemporary, the Australian actor Rebel Wilson sued Bauer Media in 2017 over a series of ‘malicious lies’, including that Wilson’s upbringing had not been quite as ‘bogan’ as she maintained. (The word was used repeatedly by Wilson herself as a mode of self-description in court, outlining the ways in which she qualified, including selling pet products and spending weekends at dog shows.) Wilson was eventually awarded a record sum of $4.5 million in damages, with trial judge Justice John Dixon telling the Supreme Court of Victoria that the damages were so large because the stories caused her reputation to be damaged ‘in a manner that affected her marketability in a huge worldwide marketplace’. Apparently, this included the loss of roles in Trolls and Kung Fu Panda 3. The proceedings also involved the testimony of Wilson’s mother, Sue Bownds, who stated: ‘I accept I’m a bogan. I live, and teach, in the western suburbs of Sydney.’ Evidence was presented about sleeping arrangements in the house when Rebel was growing up. The names of Rebel’s siblings were also considered relevant.

Even politicians want in on it. When Kevin Rudd blundered his way through an Australian colloquialism with his famous ‘Fair shake of the sauce bottle!’, he was attempting to adopt the speech patterns of the average ‘sheila and bloke’. What is perhaps more surprising is that Rudd grew up on a dairy farm in Eumundi, Queensland; the problem was simply that he sounded like he grew up in Vaucluse, raised on truffle and caviar. It’s remarkable that he sounds more natural in Mandarin.

‘Class’ has become an odd category

Class is going to tell us something about how people live, about their opportunities and their aspirations, about the material conditions of their lives; but the way we use the term is also diagnostic. Class tells us something — but the way we perceive class will also tell us something. In his influential book The Making of the English Working Class, British historian E.P. Thompson wrote: ‘In the years between 1780 and 1832 most English working people came to feel an identity of interests as between themselves, and as against their rulers and employers.’ But the challenge has always been whether or not people still feel that they are bound together by class bonds in the way they might have in the nineteenth century. These days, people seem more secure in the other two social designations that comprise the trinity of sociological analysis — gender and racial identities — than in class. Working-class people are often keen to label themselves middle class — and middle-class people are often wont to give a sense of themselves as coming from tougher circumstances than they actually did.

‘Class’ has become an odd category. Where it once designated a purely economic reality, we now define class in relation to something we call ‘socio-economic status’. The scientific smell of the compound phrase is misleading; in addition to the ‘economic’ we’ve added something called ‘socio’, although nobody is quite clear about what that entails exactly — all vagueness is pre-loaded into the prefix. Even so, with all requisite definitional caution, I’m pretty certain I’m middle class. But what about the electrician who came over while I was writing this essay and told me that the wiring at my place (which I rent) was similar to that in one of his (four) investment properties? He’s a tradesman who grew up in Penrith, left school at the start of Year Eleven, the youngest son of Italian immigrants. He’s in the process of buying another place now because ‘it’s a buyer’s market’. Is he working class? I don’t know. I still think I’m middle class. But, like Wittgenstein’s onlooker watching the builder and his assistant, my equivalences could be off. I do get things wrong — on the regular. My privilege offers me absolutely no help here.

Featured photo of Coogee Beach by Manny Moreno for Unsplash;

Painting of boy in dentist’s chair by Kurt Ard I The AutoEthnographer