“What wild creature is more accessible to our eyes and ears, as close to us and everyone in the world, as universal as a bird?”

David Attenborough, Nature Historian

AUTHOR’S MEMO

Terry Graff is a visual artist and an avid bird watcher. Birds consistently appear throughout his work, and have been a persistent theme since childhood. Through word and image, he recounts his childhood memories of birds, tracing the important influence that his early experiences and drawings of birds have had on the development of his present-day artwork. Far from an expression of the seductive aesthetic beauty of birds, Terry presents a phantasmagorical vision of the “avian cyborg”, bird-machine hybrids that speak to the conflicted relationship between nature and technology and the dramatic catastrophic disruption of the natural systems upon which all life depends. They are allegories for our human condition in an age of ecological collapse.

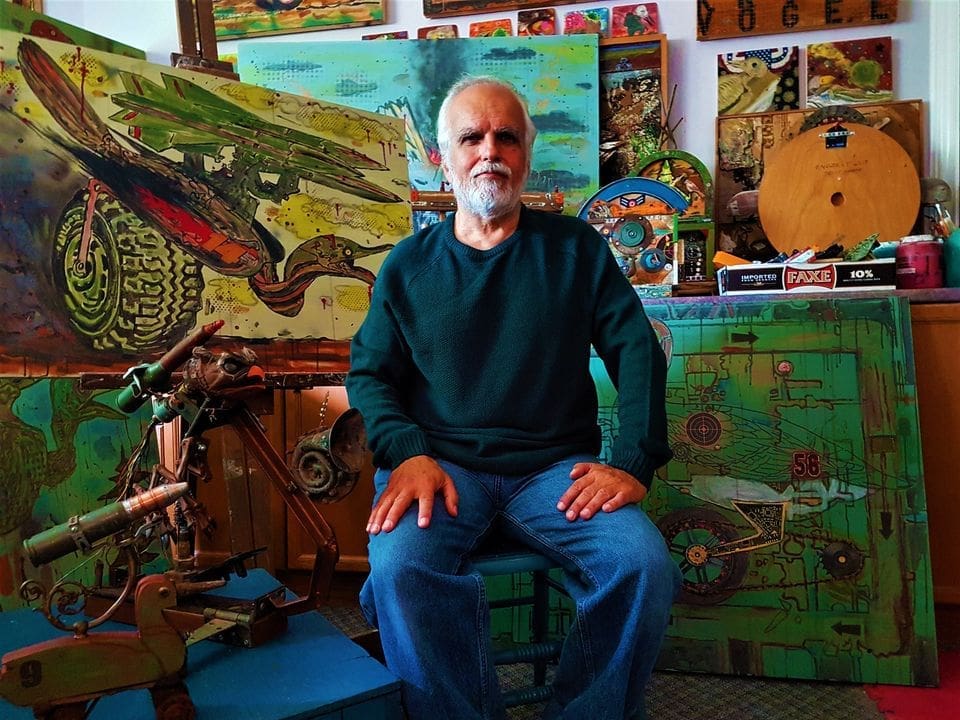

Photo of Terry Graff

I have long been an avid bird watcher with a special interest in ornithological iconography in art and natural history, not only because of the sheer aesthetic beauty and diversity of birds, but also because of their rich visual symbolism and integral connection to our human experience. At the same time, I’ve been equally fascinated by the aesthetics and function of machines, their dominant presence in human culture, how technology is tightly woven into our daily lives and how it has shaped present-day society both for better and for worse.

In retrospect, it was inevitable that birds and machines would converge in my work as a life-long exploration and expression of the relationship between nature and technology through the creation of avian cyborgs, the genesis of which can be traced back to my early drawings of robots and of the bygone birds of my childhood.

Illustration by Terry Graff

As a kid growing up in the 1960s, I collected bird skulls, feathers, and nests, and assembled and painted numerous plastic Bachmann bird model kits (owl, cardinal, cedar waxwing, blue-jay, hummingbird, and so many more), which I fastened to an actual tree installed in my bedroom. A prized object was “The Visible Pigeon”, a life-sized anatomical model that included the bird’s vital organs and skeleton. I also collected bird trading cards from “The Great Outdoors Canadian Birdlife Series” that were inside packages of Big “G” cereals, as well as the complete set of Brooke Bond cards in the series “Song Birds of North America” and “Birds of North America” issued by Red Rose Tea. I remember gluing the Brooke Bond cards into albums that I sent away for in the mail by taping a quarter to the order form.

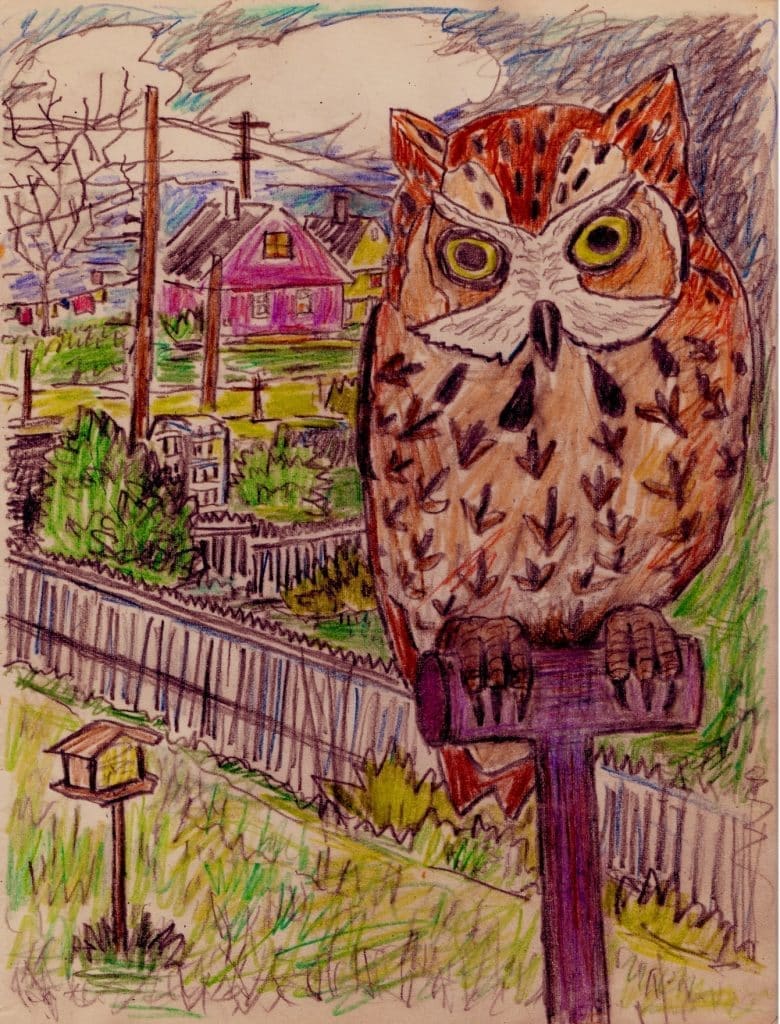

Illustration by Terry Graff

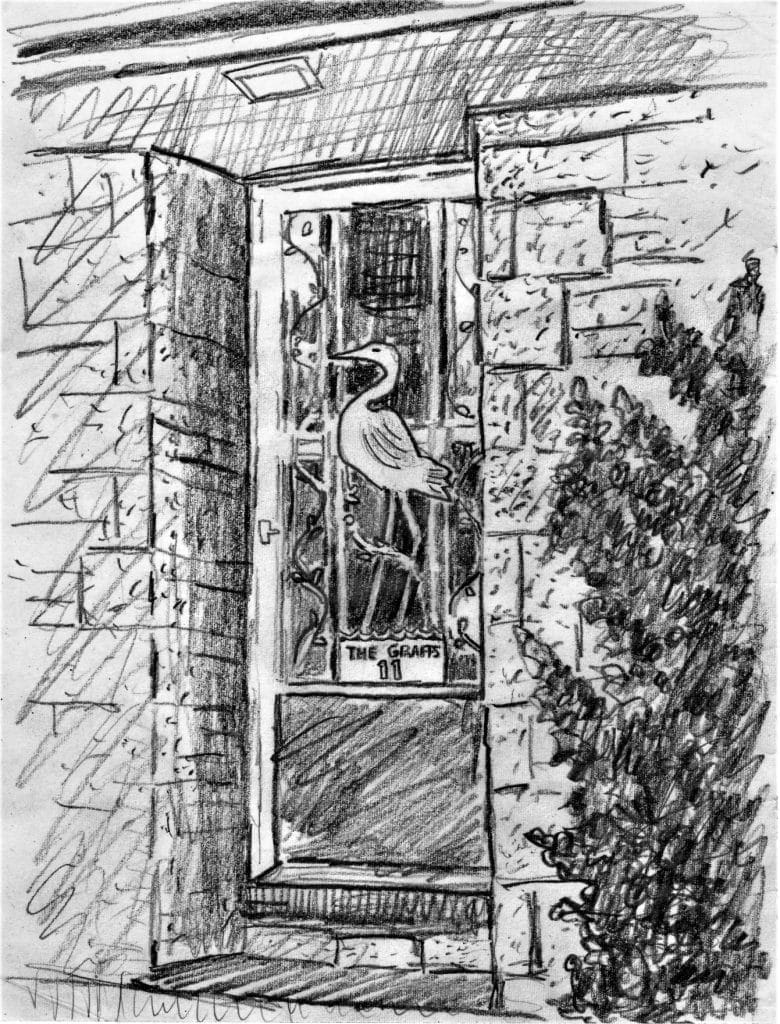

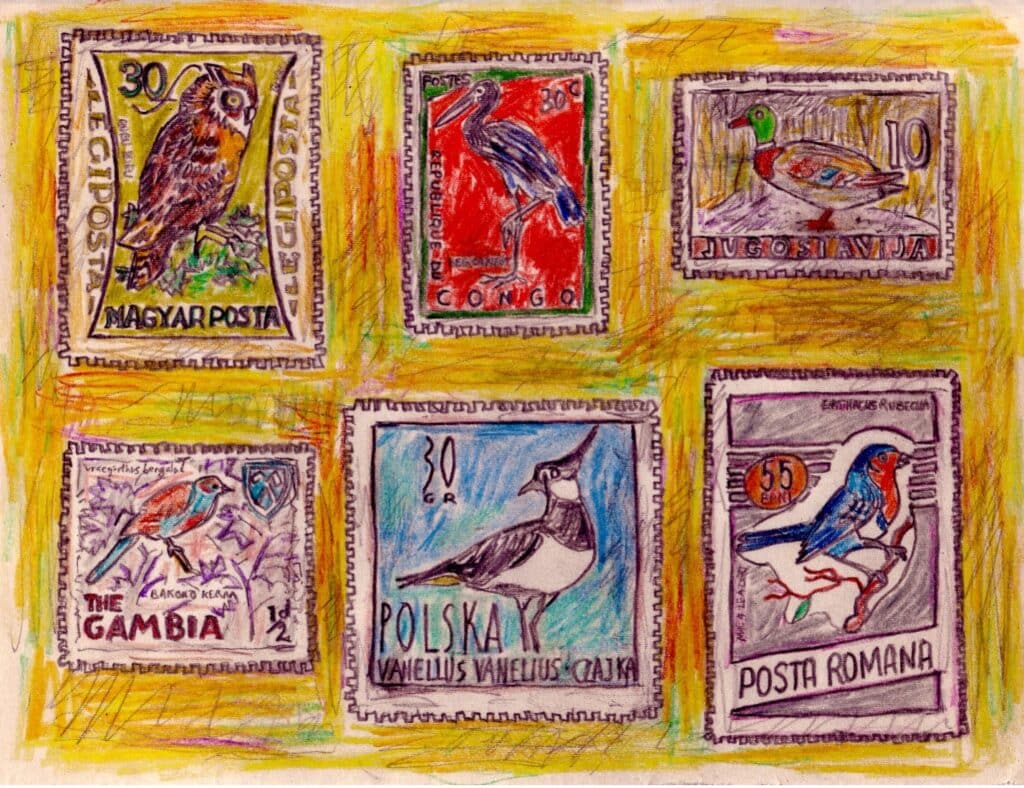

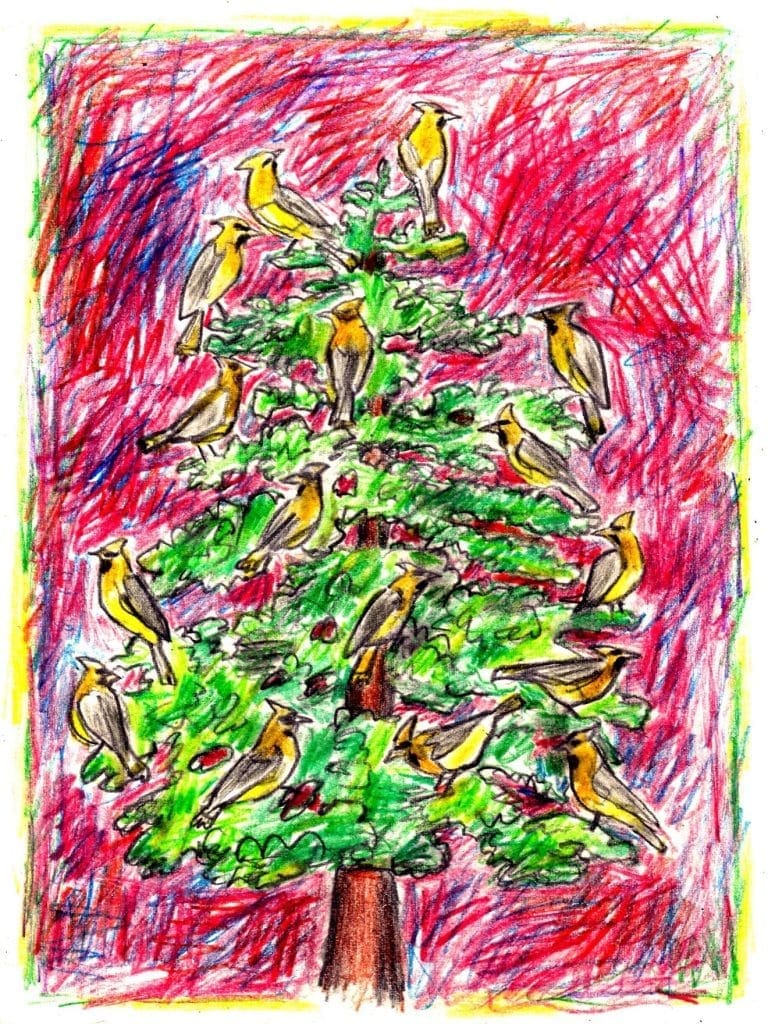

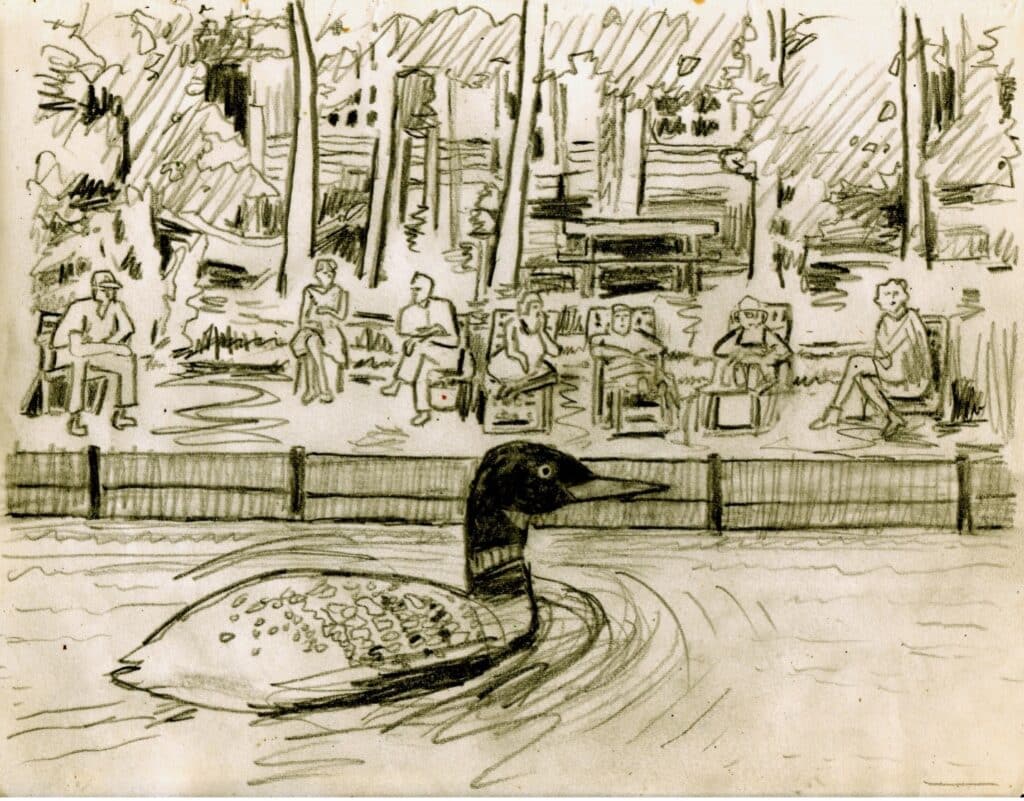

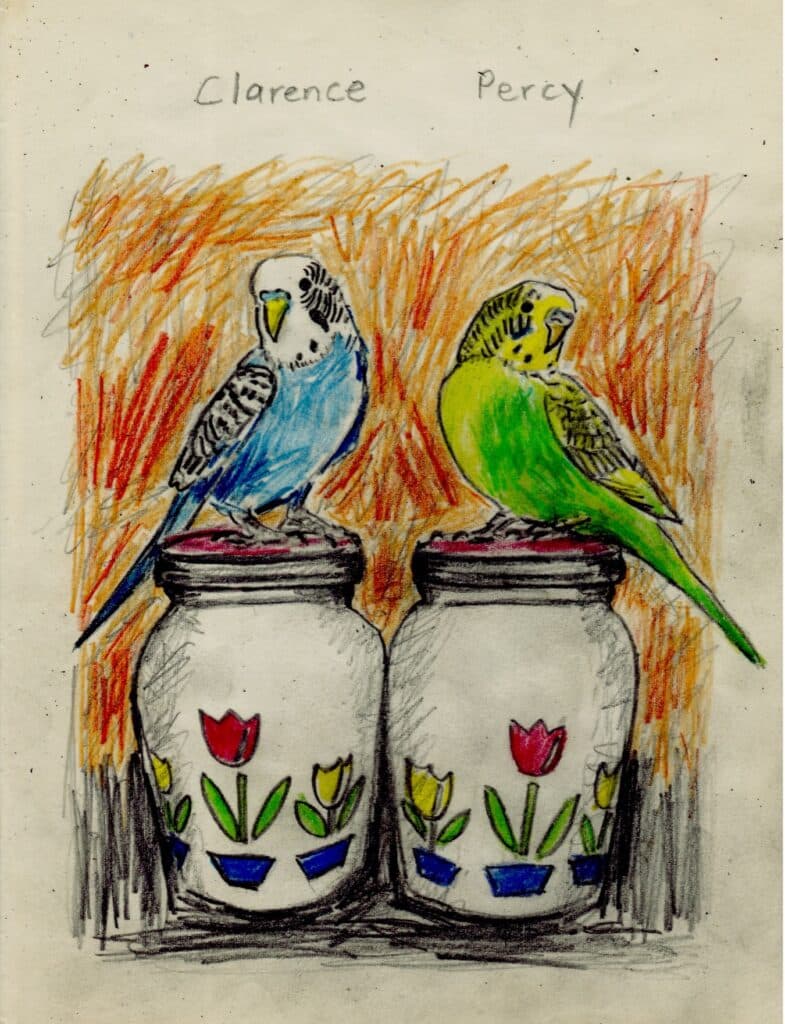

My childhood sketchbooks are filled with numerous drawings of birds based on my collection of bird models and the porcelain bird figurines that came packed in boxes of Canadian Tender Leaf Tea. Other references include book illustrations, photographs, and the variety of birds depicted on postage stamps, the large metal heron that was featured on our ornamental front door, our pet budgies Percy and Clarence, and of course the many birds that populated our backyard, as well as the sand swallows and loon at our family’s cottage. More than nostalgic recollections of simpler times, these drawings are a revealing window into my former self, into my early enthusiasm for birds and for art, and into my formative perceptions and internal thoughts about nature, ecological relationships, and the interdependence of all things.

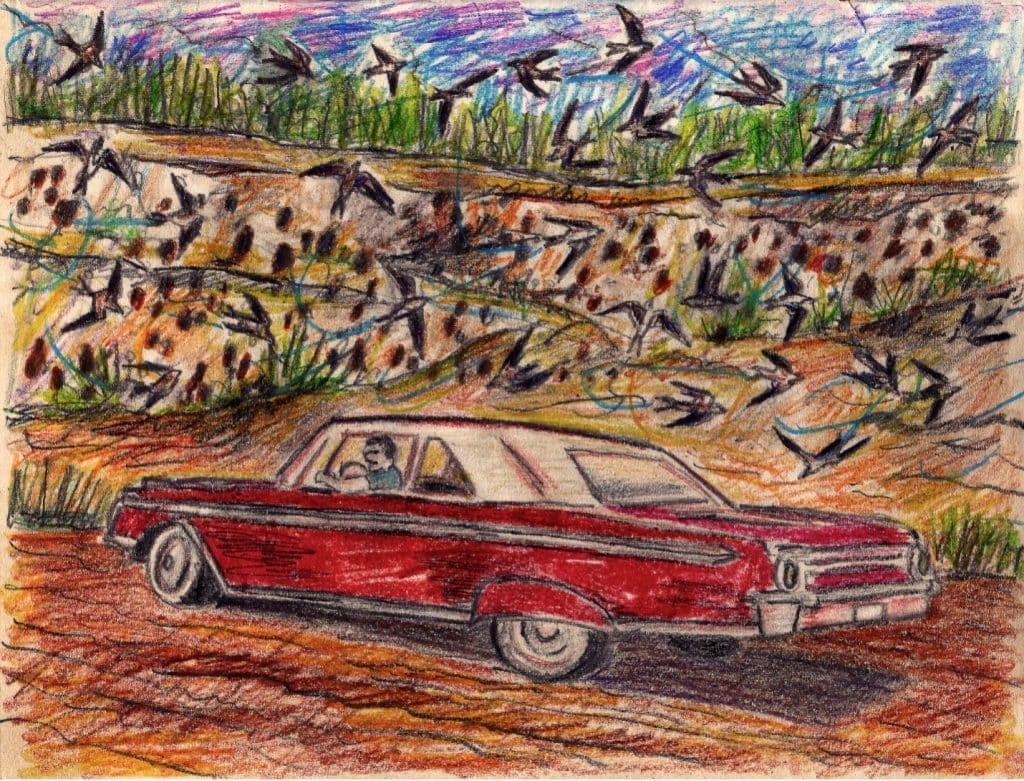

Illustration by Terry Graff

Birds were ubiquitous in our neighbourhood. The homemade bird feeder that my dad made was always bustling with a variety of feathered friends, hummingbirds were frequent visitors to the tubular blossoms of our trumpet vine, a multi-complex bird house was always occupied by a host of chirping sparrows, flocks of cedar waxwings would sometimes suddenly appear in our cedar trees to eat the berries, and crows would raid the vegetable garden. Our neighbours had families of starlings that nested in the roof spaces of their houses, and their loud chirping would wake me up in the morning. One of our neighbours raised trained pigeons that would circle above our house several times throughout the day, another had a rooster that would crow whenever it felt like it (morning, noon, and night), and there was always a raft of ducks splashing in nearby Tutton’s Pond, now called Churchill Park. When I reflect on the past, these childhood encounters with birds are a prominent touchstone that influenced my perception of a wondrous and enchanted world. As foundational experiences from which my early artwork emerged, they remain a source of inspiration and of ever-unfolding images, thoughts, and truths to this day.

Illustration by Terry Graff

In stark contrast to the enduring memory of this near-mythical peaceable kingdom, of a golden childhood growing up with nature in Galt (which was originally called Shade’s Mills and today is called Cambridge) was the machine world of industrial southern Ontario. My father, who was a strong role model, worked for Canadian Brass Limited and invented a copper compression ring that was patented in 1970. He was the quintessential handyman, a mechanic who kept my car in good running order, and once fabricated a stainless-steel muffler for it. He built the family home in the 1950’s with his own hands (carpentry, masonry, plumbing, electrical, etc. – basically everything involved in the construction of a house, including digging out the foundation).

Illustration by Terry Graff

My dad had all kinds of tools and machines, and taught me how to use them, even how to drill a hole through glass. When I was sixteen, he gave me his motorcycle and got me my first job grinding metal parts in a local machine shop. Other employment in several factories followed on assembly and production lines, welding truck mufflers, grinding and riveting metal, spray painting and assembling industrial electrical boxes and enclosures, operating a die-press for making truck cabs, undercoating cars, printing PVC film, and handling car parts for General Motors.

Illustration by Terry Graff

These formative experiences influenced both the content of my art and my interest in working with industrial materials. They also convinced me that I did not want to spend my entire life working in a factory, where I saw a press operator lose both of his hands from a machine that malfunctioned. Further, the disjunction between the uncreative, piecemeal work of the assembly line and my father’s resourcefulness with materials and intuitive understanding of machines was a significant factor in the direction and evolution of my art practice and theoretical concerns. Even at a very young age I was acutely aware that something was amiss, that little harmony existed between the natural world and ever-encroaching urban and industrial development. As my hometown grew and evolved, certain idyllic sites where I had experienced the magic and wonder of nature were trampled upon, degraded, and some were completely obliterated, including the field behind our house, which was converted into a parking lot.

Illustration by Terry Graff

I remember being shocked by the great bird shoot in the 1960’s and the ominous sight of countless starlings falling from the sky and landing in blood splatters on roads and sidewalks. City officials had contracted a group of gun-wielding hunters to open fire on a perceived bird problem. I am still haunted by this memory and the disturbing experience of witnessing a neighbour sticking firecrackers in the mouths of baby birds and watching them explode. A recurring apocalyptic dream in my childhood, perhaps prompted by these experiences, was of animals crying out, victims of some rabid fit. They were anaemic, wheezing, bleeding, vomiting; their eyes were burning, their tongues were hanging out. Confused, then crazed, they fled frenetically across a lake of ice that was breaking up as balls of fire fell from the sky. Some of the animals burst into flames, and all of them fell through the ice, swallowed whole, and disappeared.

Illustration by Terry Graff

Since the 1970s, whenever I returned home, I would look and listen for my feathered friends that I enjoyed so much in my youth. As the years passed, I noticed they were dwindling both in number and diversity. Today, it is reported that 30% of birds in North America, or 3 billion birds, have vanished since 1970 because of habitat destruction, pesticide overuse, industrial interference, changing climate, and other human-related causes. Already threatened by deforestation, birdlife in the Amazon, a key biome for birds and important buffer against climate change, is further imperilled by blazing fires from slash-and-burn methods of farming. Indeed, birds are literally the canary in the coal mine, their declining population a barometer of the environmental health of the biosphere under siege. Rachel Carson’s 1962 environmental science book “Silent Spring” was the bellwether, aptly titled in reference to the fact that the unchecked growth of industrial society would eventually render the birds that sang outside her window extinct.

Illustration by Terry Graff

I’ve always had an excellent visual memory and creative imagination, and believe my predilection for drawing birds had to do with some indissoluble blend of the effects of both ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’. I thought of myself as an artist and drawing as my superpower as far back as I can remember, concepts that were not only reinforced by my parents, but by my Kindergarten teacher who invited me to paint a twenty-foot mural of Santa Claus and eight reindeer for the wall space above the chalk board, and also by both fellow students and adults who would commission drawings of birds and other animals from me. The first badge I earned as a cub scout was, of course, the artist badge. As I got older and matured as an artist, I came to realize how influential such childhood memories are, and how important the emotional honesty and playful, creative aspects of my early art making activities have been for the direction of my work, for my sense of self and the world, and for my narrative identity as an artist. In fact, I have sometimes reinterpreted my childhood drawings and ideas from my adult perspective using my current way of working.

Illustration by Terry Graff

Recognizing my early unbridled enthusiasm for art, my mother managed to enroll me in weekly adult art classes at the YWCA in the early 1960s, as there were no art classes offered for children in my home town at the time. Also, as a kid, I studied oil painting at the Homer Watson House in Doon, Ontario. Homer Watson was a central figure in Canadian landscape painting in the late 19th century and early 20th century. The plein air painting classes took place on the banks of the Grand River, which appear in some of Watson’s paintings. I can still recall the colours, smells, textures, and sounds of that experience, and particularly the many birds that lived in that landscape, which I would invariably include in my paintings and draw with oil pastels or pencil crayons.

Illustration by Terry Graff

Although birds were a favourite subject, there are many early drawings that are a visual diary of the things and activities of my childhood, such as cottage life, Christmas and Halloween motifs, and the family dog. In 1961, at age six, I made a drawing of a Jack in the Pulpit (my favourite wildflower), which my mother entered into a contest organized by CK.C.O. TV’s Big Al’s Ranch Party”, and for which I won a tricycle. In the 1960s, on cub scout camping trips in Drumbo, Ontario, I would dig up Jack in the Pulpits and Trilliums by the roots with a spoon and take them home in empty tin cans filled with dirt. My mother helped me transplant them in our backyard garden where they thrived (and multiplied) over many, many years.

Illustration by Terry Graff

I am fortunate that my mother saved my childhood drawings, including one of the various versions I did of a Jack in the Pulpit plant. Many of the drawings are straightforward renderings of subjects in nature — birds, animals, trees, wildflowers, etc., often derived from our backyard, but many reflect an interaction and uneasy tension between nature and technology, a theme that has never left me, manifesting in both my elementary and high school art and becoming even more pronounced in the work I made in art school and later in my teaching as an art educator. The two series of lesson plans that I developed for my Bachelor of Education degree at the University of Western Ontario were titled “Art and Nature” and “Art and Technology”, both published by the Canadian Society for Education Through Art, University of Victoria, in 1982, preparatory work for my 1991 Master’s thesis in Art Education “Ecological Vision: A New Model for Art Education” from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

Illustration by Terry Graff

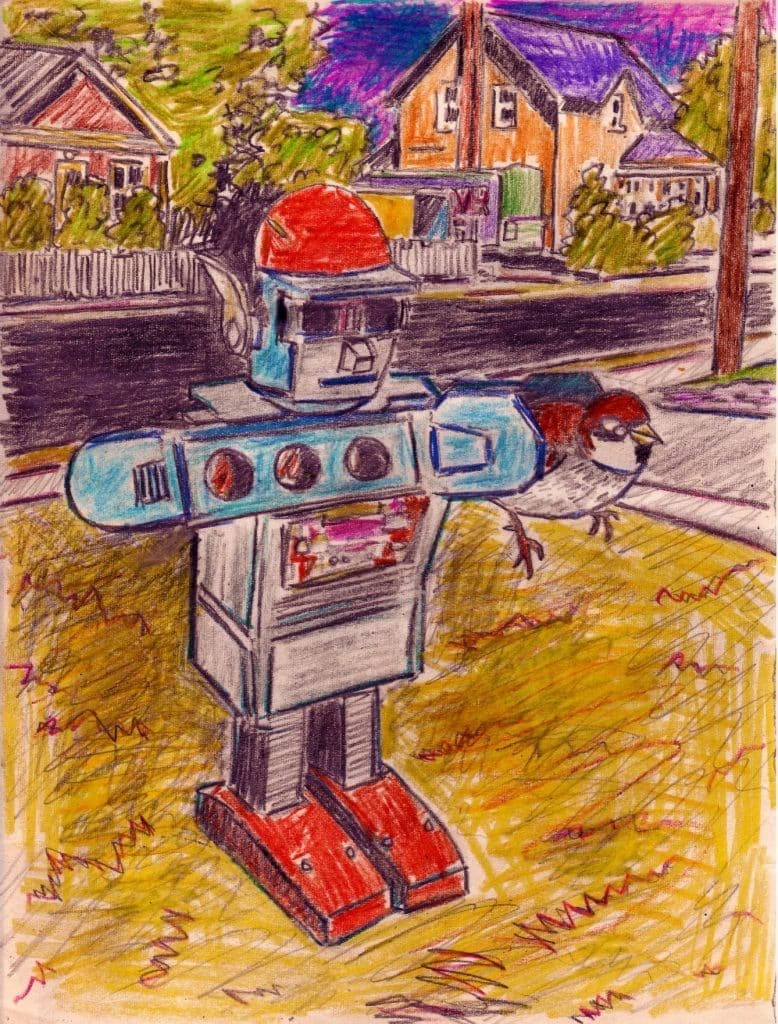

One of my childhood drawings of a robot holding a bird embodies my early interest in the relationship between nature and technology, and is possibly a portent of my later creation of avian cyborgs. Mr. Mercury, a gift I received for Christmas in the 1960s one year (I still have it), was made in Japan for Marx Toys and is battery operated with a remote control. It walks and bends over, and also raises, lowers, and opens and closes its arms to pick up and carry objects. In my drawing, the setting is the street we lived on. I don’t remember if Mr. Mercury is rescuing an injured bird, or if he is capturing it to do it some harm.

* * * * *

In Part 2, to be published in May 2022, Terry continues his exploration of birds in his work and examines his transition from producing drawings to creating avian automatons and mixed media creations: Autoethnographic Art and Essay: Ode to Bygone Birds of Childhood, Part 2 – Automatons and Mutants

Despite their seductive aesthetic beauty, I have no desire to simply paint images of birds without also including the destructive baggage of human culture. For me, to do so, would be a form of escapism that ignores the apocalyptic ecocide currently unfolding on the planet, the fact that the human species has dramatically altered the natural systems upon which all life depends through advancements in technology. Like the story of Frankenstein, my mutant birds serve as vehicles for allegory and satire.

Featured image by author