Flash Nonfiction: “The Things They Carried,” A Glimpse Into the Funeral Industry

Author’s Memo

“The Things They Carried: A Glimpse Into the Funeral Industry” analyzes the secondhand grief and experiences that morticians endure, sometimes on a daily basis. The author reflects on certain incidences she encountered during her nine years in the industry – particularly that of a murdered three-year-old she took care of.

The death care industry is often a forgotten profession. Sometimes known as “last responders,” morticians face many mentally and emotionally challenging incidents that can leave lasting effects on their life. By examining the author’s story, one can gain a better understanding of what goes on behind the scenes of a funeral, and thus increase one’s knowledge of the care and passion that goes into taking care of each decedent that passes through.

And these are the things I carry: the memories of those gone before us; the names of those entrusted to me to care for.

THE THINGS THEY CARRIED

One man had a McDonald’s receipt in his pocket. It was his last meal before he shot himself in the head with a .22. Another man came in with a plastic container of marijuana tucked in his jeans. Unsure of what to do, we placed it in the crematory with him. And then there was Susie*.

Susie didn’t carry anything with her; she was only three years old when she was murdered by her mother’s boyfriend. Her older half-brother, however, carried a pink teddy bear to place in the casket. Out of the thousands of cases I’ve witnessed, Susie’s was the one that embedded itself into my heart like a shard of glass.

The first time I had seen a dead child was five years prior. He, too, was a murdered toddler. I witnessed his embalming briefly before stepping out of the room. I cried the entire drive home from work. But my time with Susie was different. I didn’t embalm her, but I was tasked with the privilege of dressing her.

I had been in communication with her family during the arrangements and learned several things about Susie: her favorite color was pink; her favorite song was “Here Comes the Sun” by The Beatles; she loved her redheaded doll from the Pixar movie Brave. Her family brought in a rose-colored dress and tights with a matching bow. They’d selected a small, white casket.

In the preparation room, I played “Here Comes the Sun” on repeat as I placed the tights on Susie, then her dress. I gently slipped the bow over her head, covering the bruises on her skin. The other director, Carl*, had told her family that she wasn’t in proper shape to be viewed. I disagreed but didn’t argue with him. I just did the best I could.

When I was finished dressing her, I didn’t need the body lift (an electric machine used to lift the deceased in order to place them in a casket). Susie didn’t weigh more than twenty-five pounds. I gingerly placed one of my arms under her knees and the other under her back, then carried her to her pearly white casket. I gently laid her inside as if tucking a child into bed.

This final moment with Susie etched itself into my mind. God gave me this opportunity to show one last act of love to someone who had experienced a horrendous, violent death at only three years old.

Susie was buried in a country cemetery with only family, Carl, and me present. It was a beautiful autumn morning, and the trees were shades of tangerine and amber. I can still hear her family telling Susie’s brother, “Susie is playing with Jesus in heaven. Once you get to heaven, she will say, ‘What took you so long? I’ve been playing and playing this whole time.’”

There was one thing Susie’s family carried, along with every person who walked into the funeral home: an inexplicable grief accompanied by an absolute emptiness in their hearts. You could feel the weight of a person’s loss by the way they tenderly shook your hand, or gazed longingly at a photograph; the way they held back tears, or crawled onto the viewing table to hold their child’s body.

The way they forced themselves to speak in the past tense about their loved one.

And these are the things I carry: the memories of those gone before us; the names of those entrusted to me to care for.

*Names and identifying features have been altered to protect the identities of those in this story.

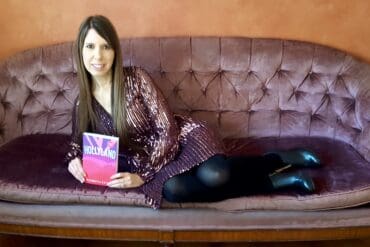

Featured image by Ria Sopala from Pixabay