After the School Shooting: Living In a Death-Denying World

Author’s Memo

Since the shooting at Columbine High School in April 1999, there have been more than 377 school shootings in the United States (Cox, et al, 2023). The UNC Charlotte campus in Charlotte, North Carolina, while I was a faculty member, experienced a school shooting on April 30th, 2019, in which two students were killed and four were wounded, three critically, by a university student. This paper, both a narrative and poetic account of a school shooting, provides an experiential entry into the experience from the point of view of a faculty member.

The shooting occurred during the last day of classes of the spring semester. Following the shooting, the school went into lock down for approximately five hours, during which students, faculty, and staff on campus were holed up in classrooms, offices, and closets. Afterwards, final exams, which were scheduled to begin two days later, were cancelled, and all final work for the semester became optional. Also, there was an on-campus vigil on May 1 which was attended by 7500 people. Faculty, while dealing with their own emotions from the shooting, had another responsibility which was to simultaneously comfort students while determining how to compute final grades.

“In taking the reader through the experience and aftermath of a school shooting, this work invites the reader to consider what it’s like to live in a gun-worshiping culture that is desensitized to death.

I was teaching a class on End of Life Communication that semester, and although I study communication in the context of death and dying, this mass shooting shattered my illusions of safety and control and challenged my ability to function. I was, simply, not only afraid and angry, but also traumatized and anxious, and I still had to administer exams, grade papers, and support terrorized students, and struggled through the end of the semester in a daze of overwhelming workload and emotions. There was no comfort, and, for those weeks and beyond, I was deep into what I would term my own dark night of the soul. In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, rational thought and linear communication were useless; I was mainly able to express myself though poetry.

So, in taking the reader through the experience and aftermath of a school shooting, this work invites the reader to consider what it’s like to live in a gun-worshiping culture that is desensitized to death.

References

Cox, J. W., Rich, S., Chong, L., Trevor, L., Muyskens, J., & Ulmanu, M. (3 April, 2023). More than 349,000 students have experienced gun violence at school since Columbine. Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/interactive/school-shootings-database/

The Notification

The evening of April 30, my husband Jerry and I go out to dinner and a jazz concert with friends. While we stand up to leave the restaurant, I turn on my phone to check for messages.

“101 messages,” the notification pops up.

“Oh my God,” I say, “I have over 100 messages. What’s going on?”

I stumble out the door of the restaurant while I frantically scan my phone.

“Run. Hide. Fight. There is an active shooter on campus,” the UNCC notifications reads.

I have to read it three times before the message sets in.

I read through the barrage of texts.

5:50 p.m.: NinerAlert: Shots reported near Kennedy. Run, Hide, Fight. Secure yourself immediately. Monitor email.

6:03 p.m.: Active shooter on campus. Is everyone safe? Anyone need anything?

6:04 p.m.: Safe.

6:04 p.m.: Home.

6:04 p.m.: I’m home. Is everyone else okay?

6:04 p.m.: Safe

6:04 p.m.: Safe actually just got home

6:04 p.m.: Got text too. I’m not on campus, hope everyone is ok!

6:04 p.m.: Home, too.

6:04 p.m.: I am home. Thanks for checking.

6:04 p.m.: According to news 3 people have been shot in Kennedy building.

6:04 p.m.: I’m home!

6:05 p.m.: Safely locked in Denny 105 with my students

6:05 p.m.: Safe

6:05 p.m.: First Years are safe

6:05 p.m.: Safe.

6:05 p.m.: NinerAlert: Campus lockdown continues. Remain in a safe location. Monitor email and UNCC homepage.

6:05 p.m.: Safe.

“6:03 p.m.: Active shooter on campus. Is everyone safe? Anyone need anything?

6:05 p.m.: All first year grads are safe. Most off campus. One student is locked in a kitchen in Cone but is okay.

6:10 p.m.: I’m working in Res Halls. Currently rounding up students.

6:10 p.m.: I heard an arrest has been made

6:13 p.m.: I’m locked in 1018

6:14 p.m.: I’m safe

6:18 p.m.: I’m with two UGs in the FERPA office in grad suite. Locked up tight

6:22 p.m.: Good

6:22 p.m.: Good

6:23 p.m.: I’m okay.

6:24 p.m.: I’m good

6:24 p.m.: I’m locked in the library

6:27 p.m.: I’m home safe.

6:28 p.m.: NinerAlert: Campus lockdown continues. Remain in a safe location. Monitor email and UNCC homepage.

6:31 p.m.: I hear it is an anthropology class. Medic is now saying more than three people.

6:32 p.m.: Oh wow.

“6:24 p.m.: I’m locked in the library

6:43 p.m.: NinerAlert: Buildings being swept by law enforcement. Law enforcement is individually sweeping buildings on campus. Also follow officer commands.

6:49 p.m.: Omg

6:49 p.m.: Yes. 5 shot, 2 have died

6:57 p.m.: I think all grad students are accounted for now.

7:03 p.m.: I’m now off campus, finally … phew.

7:04 p.m.: Good.

7:04 p.m.: NinerAlert: Campus lockdown continues. Remain in a safe location.

7:04 p.m.: I’m still in Colvard.

7:06 p.m.: I’m also in Colvard; waiting for police

7:06 p.m.: Officers will come get them soon. They will have to leave their stuff and get it later.

7:08 p.m.: I’m still in Cone

7:09 p.m.: I’m still in Atkins

I scan the deluge of messages and frantically try to identify the senders of each one. I mentally go down the hallway of our building, trying to identify who has been accounted for and who has not.

8:48 p.m.: NinerAlert: The campus remains on lockdown while police clear each building. This could take several more hours. Also check email for more details.

I spend the rest of the evening in shock and, later, I lay in bed, eyes wide open, thoughts racing. This will be obviously my sleep pattern for weeks.

“I spend the rest of the evening in shock and, later, I lay in bed, eyes wide open, thoughts racing. This will be my sleep pattern for weeks.

10:51 p.m.: NinerAlert: ALL CLEAR. Campus lockdown has been lifted. Kennedy building remains closed due to active crime scene. Continue to check campus email and emergency.

The next morning, the sun inexplicably rises. I am angry that it won’t let us mourn in darkness. I don’t want to get dressed.

First Day After the School Shooting

How do they take their exams, deciding

their future, with their heart still pounding, fear

in their throats, frantic mem’ries, surviving

(some did not) a meeting with Death, terror

storming the mind, the test faced now appears,

our collective test, the only fact we

must learn, forty-thousand dead last year

from guns, breath-taking, can you guarantee

my students they will not die today, me

that my next lecture will not be my last,

war zone, hell on earth, no one, nobody,

should fear they will be shot sitting in class.

As I breathe in the aftermath of death,

I fear the holy has escaped with their breath.

The Vigil

I just want to be alone, and I click past the notice for the vigil.

Our department chair emails, we’re going to the vigil together. I go and I’m glad I do. I feel a strange sense of anxiety as I get closer but I’m glad I’m there with Jerry, colleagues, and students.

Second Day After the School Shooting

How can rustling trees dance their wild dance,

shimmering leaves, birdsong symphony;

how can sunshine in the sky take a chance,

When not yet buried in the grave is he?

How can butterflies, fly so carefree,

How can trees still stand, earth still turn,

How can clouds float across the sky, lazy,

When mourners have not begun to mourn?

Why don’t meetings, work, email, adjourn?

I need some space, time to pause today.

I’m drowning in emotions and concerns.

I need to not have to know what to say.

I do know I will have to find a way,

But I’m a little raw right now to start.

So can’t I wait until a better day?

I skinned my knee, only it was my heart.

The Names

Following these, on the third day, we hear the names of the victims. At this university of almost 30,000 students and 5,000 faculty and staff, I do not know the professor or any of the students, despite one of them being a major in our department. I grieve anyway, because today all students are mine and all faculty are my colleagues.

The sun rises again the next morning, offending me again. The university has announced they are cancelling exams; no, wait, exams are now optional; we have to let students know what their grades are at this time so they can decide whether to do more work or stay with the grade they have. I send a message to my students that they are welcome to come talk to me to process the experience. “I’m not a therapist,” I warned, “but I do study end of life communication.

Maybe I can help you process it, if you want to talk.” One student comes to talk to me, and I find myself at a loss for words. I can think of nothing to say. My voice sounds hollow. I speak of unimportant things, grading and writing tests, and I wish I could will my chatter to stop. But I am afraid to let silence in.

“Why did he do this?” my student wants to know.

I offer the small amount of information I have gleaned from the news. “Well,” I say, “his mother died.”

My student raises his eyebrows. I know from class his own mother died when he was in high school. He has not killed anyone.

“I know,” I say.

I am an imposter and a failure as a professor if I can’t comfort a student.

“I am an imposter and a failure as a professor if I can’t comfort a student.

I offer an extra credit assignment to my “End of Life Communication” students—to submit a journal writing about their experience with the shooting. I figure that will be therapeutic for them and am trying to find ways to give them extra points to make up for the horrible circumstances surrounding this last week of the semester.

I work around the clock to finish my paper grading a week earlier than originally planned, so my students can make the decision whether or not to forego their final exam, but I find I cannot summon the necessary discernment or judgment to subtract points for errors. My syllabus always states that I will not round up points, “I am not a points Santa Claus,” I have said. Now, though, I am passing out points like candy off a Mardi Gras float.

The Grief

My grief comes in waves. Then, I awake and think I am doing well. One student turns in her extra credit journal, and I read it while I am getting dressed to go into the office. She tells of watching a classmate bleed to death in front of her. Another injured student is a friend of hers. She is also traumatized and angry. Very angry. I cannot continue to dress.

Fifth Day After the School Shooting

Some may say world’s end occurred that night.

Yet, I awake. Life persists after all.

Sunrise encroaches on darkness, first light,

as day, in turn, always ends at nightfall,

stars shine enough, night sky overhaul.

Dusk, meditation, gin blur the eyes

–whatever helps you survive this downfall—

from sameness, safety, I empathize—

stare into hate long enough, spirit dies.

Can’t our hearts break; feel the grief, feel the pain;

in the decay’s where resurrection lies.

Our world ended that night in a heart stain.

Holiest of holies sometimes speaks

in whispers. Or wails of distress, tear streaks.

The Shrine

There is a makeshift shrine on the steps of the Kennedy building where the shooting occurred, rocks and white candles, burning, and bouquets of flowers, notes that read “Niner Strong!” Meanwhile, I stand there with a colleague and let the expressions of grief wash over me. There is also a young woman lighting candles amid the cellophane flower wrappings and I wonder if the wrappings might catch on fire. I have another fleeting thought that would be wonderful, a bonfire burning this hall of hell, to have a tangible manifestation of the smoldering embers of our community.

Colleagues add a “Niner Strong!” frame on their Facebook photo. I don’t blame anyone for finding hope in visions of strength, but cannot bring myself to push the button that transforms this tragedy into a slogan. Thereafter, I am not ready to be strong and I want to lose myself in those candles, flame, blue heat burning off the pain, smoke signals into the heavens, messages to our students, “We failed you.” “I am sorry.”

Fifteen years earlier, when I moved to Charlotte from Florida, I arrived at our new house in late August, one week before classes began.

My husband asked me to run to the grocery store and I looked at him in dismay. Feeling the disequilibrium of a new home and looking around the array of doors leading to the basement, bonus room, garage, and front door, I responded, “I don’t know where the grocery store is! I don’t know how to get out of this neighborhood! I don’t even know how to get out of this house!”

A week later, when, on the first class of the first day, I walked into my first classroom of the new semester, I breathed a sigh of relief. This I knew.

“Now, I feel the same disequilibrium I felt 15 years earlier.

Now, I feel the same disequilibrium I felt 15 years earlier. I know how to lecture and facilitate discussion, how to grade a stack of papers with precision and compassion, how to enforce deadlines and standards. I do not know how to talk traumatized students through flashbacks of a friend bleeding out in front of their eyes; how to hide in lockdown for five hours not knowing if you will live or die while comforting students; how to help grieving and traumatized students navigate hourly changes in grading and exam policies when they are terrified to step foot on campus; how to be prepared to stare down the barrel of a gun while shepherding dozens of students to safety.

Faculty work tirelessly to accommodate various needs from a myriad of students who want nothing more than to turn back the clock 7 days. If we were Jewish, we would still be sitting Shiva. Instead, we are crumbling and trying to hold it together with paperwork and meetings. Pretend normalcy.

The seventh day after the shooting, the shrine on the steps of Kennedy disappears, presumably to whitewash the campus before commencement ceremonies in two days. Since then, my grief remains in full color.

Eighth Day After the School Shooting

It’s called mortality salience.

I know, I study this stuff.

It’s anxiety tightening around my eyes as

I see campus for the first time since,

looking into eyes bloodshot in exhausted faces,

tears at their corners,

bodies falling in our fretful sleep.

I scan the paper, we are yesterday’s news,

students shot dead in classrooms are everyday sights.

Mortality salience.

I scan the landscape for last week’s memorial flowers on the schoolhouse steps;

the steps lay bare.

Ghostly memories of last week’s lit white candles lingers;

the classroom building itself, a visual monument to death.

Everywhere I look, a reminder.

These eyes remember what they didn’t see.

Mortality salience.

The picture in the back of my eyeballs haunts.

Unexpectedly traveling too close to the edge,

looking down.

Credits

Photo of a schoolbag with a badge by Colin Lloyd for Unsplash

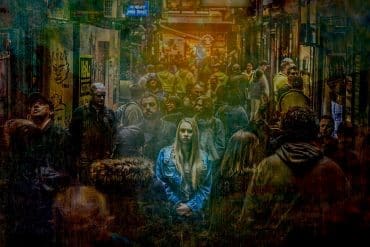

Featured Image by Chip Vincent for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Firstly, you can visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in also contributing? Secondly, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work? Then, check out our Submissions page. Please also view Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Additionally, please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Lastly, visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Christine Salkin Davis is a writer, poet and artist from Concord, NC. She is an Emeritus Professor of Communication Studies at UNC Charlotte. She writes about end of life communication in family, cultural, and political contexts. Her poetry explores her experiences with death and dying, spirituality, and social justice and compassionate living.