It is in finding these solutions, the tape and the glue that holds us all together, that we find the beauty of who we are as people.

In addition to the following interview, Jay and Marlen enjoyed a 20 minute Zoom chat about his work and his responses. You’ll find the link to the full transcript below.

MARLEN HARRISON: Your bio reveals that you’ve only recently discovered the named method “autoethnography”, but your poetic work suggests that you have been long performing cultural inquiry via reflections on lived experience. Would you tell us a little bit about how Shades came about and why you feel it is a work of autoethnography?

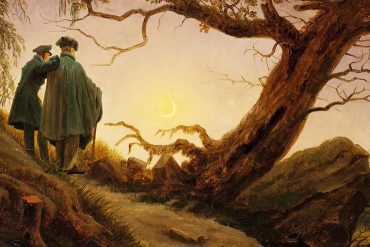

JACOB “JAY” MEADOWS: There is a through line in the collection of being lost in the woods, trying to find my way out, deciding what I do after. The entire collection is an allegory to my life in 2021: for much of the year, I was lost inside of decision making and who I was. After 2020, I was reeling from a really serious breakup, I was thrown into the thick of adulthood at the same time that COVID-19 was sweeping through the world, and I was navigating new relationships and knowledge about myself. For two years, it felt like, I was lost in the woods.

“Wondering While Wandering”

Who were we?

Where were we?

What were we?

Why were we?

To say that I was lost inside of the weight of so many issues is an understatement. It was at some point toward the end of 2020 that SHADES began to be written when my therapist told me simply, and I will paraphrase, “You’re a writer, you are having a lot of feelings. Write them down.” I had no idea that the first thing I tried to write down would come out as a poem, and I think I was more shocked than anyone.

This collection is, very simply, a year of my life captured in words. What emotion was I feeling on April 23, 2021? I have a book that could tell me just that. When I wrote the first poem, I thought it was just a one-off, but it was followed by another and another, and, to my immense surprise, I began to improve as a poet. I shared my work with my boyfriend and with my therapist and I realized that I was processing serious emotions through poetry. My therapist encouraged me to keep writing, as did my boyfriend, and so I kept writing. I found the writing to be therapeutic and would sometimes write during major world events (“America, the Weak” was written while I watched the attack on the Capitol), when processing my heartbreak and the new age of my life (“Petals for Armor” was written while I was crying and hurting, but I knew that I would come out of something painful as something beautiful), and whenever the feeling struck (“One” was written on a day that I felt like there was too much going on and I sat down and just told myself I could only do one thing at a time).

Looking at my collection and at literature in general, I have found over the last year that almost everything that I have ever read is in some way autoethnographic: after all, writers write about what they know best. Stacey Holman Jones, one of the leading voices in autoethnography, tell us that processing emotions through writing and analysis, especially confusion and pain, can be a form of autoethnography. That is precisely what I did in SHADES, and I am thankful for it every day.

MARLEN: Your book opens, “Dedicated to the beautiful, the broken, and the beautifully broken.” After reading the collection, I think “beautifully broken” could have made a great title as well. Could you tell us a little more about being “beautifully broken”?

JAY: Every human is in some way broken. Do you have an addiction to alcohol, cigarettes, love? Broken. Do you lie awake at night stressed about the next day, and the next day, and the day after that? Broken. I could list those all day, but we are all broken. I think, personally, that it has something to do with adolescence and our journey toward self-discovery: along the way we realize how many things are wrong or, here’s that word again, broken.

But what I have realized is that broken people are beautiful. My pain allows me to help people. Because I have been in therapy for years after battling panic attacks, I know how to help people with panic attacks and I also know how to assuage my own emotions with the gliding of a pencil over paper. It is in finding these solutions, the tape and the glue that holds us all together, that we find the beauty of who we are as people.

When I was writing this, I was mending myself with poetry. My first poem, “Open,” concludes with the line, “These words are my sutures.” I, myself, acknowledged as I was writing the broken space in which I was writing, and while I think that the feeling of being lost and not knowing up from down from left from right is important, I also knew that the “shades” I was in was a broken, but beautiful place to be. I decided to take something that should have been the worst parts of my life and made them into something grand.

MARLEN: Jay, can you tell us about your poetic process? For example: How do you start a poem? What guides you? How do you know when you’re finished?

JAY: I will apologize in advance; this will be a shorter answer. I have always been a writer. I have always had words flowing out of me: my poetry is no different. My poetic process is very simple and straightforward: I feel something, an emotion, or I have a thought, and next thing I know, I am in a notebook writing. I’m not a master poet, I do not write poems with specific meters and forms, though there is one sonnet and one villanelle in the book. I write and the words flow out.

I think that the best answer to your question is an answer to a slightly different question: how did I know when the book was done? I write my poems by hand in a notebook. One day, I looked at the poems and just decided to type them up. There it was: a book. It was an accident; I never intended to write a single poem, much less a book. I was astonished. And, believe it or not, I am still astonished when I write a poem, every single time.

MARLEN: How is the writing of autoethnographic poetry different from your more academic or literary (e.g Jay and June column) autoethnographic writing?

JAY: Autoethnography relies on one thing: self-reflection. My column for The AutoEthnographer relies on my personal reactions to Hulu’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” and news from around the world. My master’s thesis was an autoethnography on my experiences with conversion therapy and how it mirrors what occurs in Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. My poetry is the purest expression of my emotions in the moments I have them. There is always a theoretical lens when I am writing academically: queer theory or feminist theory or autoethnography. My autoethnographic poetry is simply studies of myself written in free verse.

MARLEN: Could you please select a few poems to further contextualize for us via brief author’s memos. What prompted that poem? How is it autoethnographic? What was it like to write the poem? etc.

JAY: Heartbreak is something, I have learned, that one learns to deal with as time goes on. It does not completely vanish at any point: it is something that one grows and heals around. When I wrote “Still Screaming,” I was in the midst of attempting to create my own closure for a relationship I believed would be lifelong; the poem is literally me thinking through where and when I started to hurt. Screaming is here a metaphor for asking for help, begging and pleading for something to change, to heal. I write, “I think that’s when I noticed that you / Only tolerated me – even when you offered me / Palliative utterances of / “I love you.” I was able to locate a time and place as the start of my pain in that relationship, but the last line is my simple conclusion that the pain still exists, even in the midst of a new, healthy, loving relationship: “I’m still screaming.” This poem is autoethnographic in that I was digging through the hardest parts of my past in order to uncover or create something new, and that is the work of autoethnography.

COVID-19 is, sadly, something that everyone on Earth understands. I know too many people who lost someone to the virus, and I know too many people to be understanding of the politicization of a virus. Something I have struggled with throughout the past year and a half has been the issue of masks. In the US, the Left sees them as necessary and the Right views them, widely, as an unneeded discomfort (and that is the mild, professionally-worded version of that). As a human who has seen loss, I firmly believe that wearing masks can and does save lives during a global pandemic: show me one person not wearing a mask in small, indoor spaced and you have a very angry poet. “Across the country / Black men and women must be mindful. / Don’t wear clothing too baggy, / Don’t have too many pockets. / These vestments could mark them for death. / Wearing a mask is comparable.” This poem was an expression of anger, of disbelief in the view that to not wear a mask was a mark of martyrdom. This is autoethnographic, quite bluntly, in that it is a critique of people who view this as a political issue. I have studied how I feel about the science behind masks and the feelings of loss and now I have applied that to the media of frustration and anger in “Comparable.”

Closure is one of the core concepts in SHADES, and it was something I was actively working on inside of therapy and my own self-exploration. The final poem of the collection, “Close,” explores my definition of closure, “I will create new openings / And we shall see which of those / You follow me into, / If you do.” This collection was written by a man finding closure with death, heartbreak, global strife, and personal change, and finding that closure by creating a new definition of closure. When I finished writing that poem, I think that was when I realized I had figured out my own needs as well as what the world could offer me, so I compromised. I concluded the work saying that I have learned, through pages and pages of introspection, that I would have to be content with the unknown future and the strength I have will have to be enough. Things do not close: rather people move forward, crossing paths. We must each create for ourselves closure: trust me.

MARLEN: How has having advanced knowledge about creative qualitative inquiry as a result of your scholarly pursuits influenced your approaches to writing poetry, if at all?

JAY: In my poem “Light,” I write about freedom: “I step out from the filtered / Light / Of trees and flowers and vines and branches / Into the pure and beautiful / Light / Of freedom.” I graduated with my second master’s degree, one in Creative Writing and another in English, and I realized that I had spent the past 8 years of my life writing for a specific, academic audience, and it wasn’t until a certain editor-in-chief became my professor that I knew that I could move beyond that, and I flourished. This poetry is the next evolution of that newfound freedom: pure, unadulterated autonomy. This has been and is the best parts of my education, but with a little more Jay thrown in there. I am free now, until my post-postgraduate program, to write for me and for me alone. And this is the prelude to as much freedom as I can manage in the next year!

MARLEN: What are your next steps as a poet?

JAY: “Beautiful, Brilliant Minds”

Beautiful, brilliant minds are fire,

Sometimes a candle, others, an inferno.

My mind has been an inferno of late. If writing was pouring out of me before, poems are bleeding through my pores now. I have never experienced what I am experiencing right now, and I hope that it never stops; but, I know that writer’s block can occur at any moment. I mean, I did write,

Beautiful, brilliant minds are fire,

But fire is not invulnerable.

Let’s just say that I have been capitalizing on my constant creative thinking. I do have quite a lot to say, just ask anyone that knows me.

TRANSCRIPT OF VIDEO

Featured Photo by Danielle Dabney on Unsplash