Between Low-Fat Love and A Big Life

Kismet meet Serendipity

I met Patricia Leavy, under strange circumstances that became indicative of our fantastic relationship. We were both college professors who focused on popular culture, looking for a way to make our work accessible and meaningful for more than just our few students. We met at a friend’s dinner party where we sat opposite each other and somehow connected over egg rolls and wine and yelled across the table at each other all night, finding out we had endless things in common. She was the first person I had met in ages who shared my sense of humor and so many of my fringe pop culture choices like Portishead, Tori Amos, and Nine Inch Nails.

She was on a new trajectory starting a new life. I, on the other hand, was still trying to find my voice and really myself, drowning in what appeared to be a series of unfortunate incidents, over which I believed I had no control. Patricia was the sort of person who pursues what she wants, and she pursued our friendship when I would’ve just imagined it and never spoken to her again. We started going to the movies together. I watched as she wrote Low-Fat Love, quit her job as a professor to become a full-time writer, and moved to Maine. Now she’s my sister from another mother and her choices in her life have inspired me to think more intentionally about my own, helping me see that I am kind of an awesome person and a great teacher.

‘Now she’s my sister from another mother and her choices in her life have inspired me to think more intentionally about my own, helping me see that I am kind of an awesome person and a great teacher.

It was insanely an honor for me to be able to read an early draft of Low-Fat Love and have continued to be do so for all her subsequent novels. In each case it’s like seeing inside the secret world of the writer, realizing that you just have to have focus. It’s about commitment and passion. When she asked me to write this piece I typically obsessed and overthought it until it was late, which just shows I’m still a work in process. Everything about Patricia is inspiring, even the crazy stuff she does because she does it with such charm and commitment. I could ramble on all day about our relationship and how it transformed me. But the following is going to give you a sense of the ways in which I use Low-Fat Love in the classroom and why just using it makes the world a better place.

How Social Fictions Makes Classroom Reading Meaningful

It would be no surprise to say that the biggest challenge in today’s classrooms is getting students to read. Somehow reading has become worse than math, and literature has become a word that evinces eye-rolling and a commitment to add it to the list of things they never did. I happen to love reading, love it, it’s the salve to my introverted soul, the space of endless learning, distraction, emotional connection.

As a person who is also a professor, I want to open my students up to my passions, set them on a journey to lifelong learning.Trained in American Studies I have always used literature to bring classrooms to life. But as an academic, my training had been to believe that only certain types of books and authors are appropriate for the classroom. Patricia blew up my world with the first time I read Low-Fat Love, and I became crazed with all the ways I wanted to use it.

But What is Social Fictions?

You may think the term is reflective of the academic need to label everything and squeeze things into little boxes that sociologists can lay claim to (think race or gender or culture). But social fictions are merely fictional works written with intention for the classroom, by trained scholars from any field. In short, the writer has done the work for you, thinking about the context of teaching, and the needs of both professors and students. This takes the guesswork out of choosing a text for class in meaningful ways that reflect the teaching experience of the author. I know the author wrote those questions and assignments so that they are relevant to my students, instead of the generic questions you usually get in both textbooks and online cheat sites.

Since I teach History, my students are quite happy to tell me how much they hate reading and how boring history is. Ruined by testing, they have been convinced that all knowledge is relative and the past has nothing to teach them, I have quite the uphill battle to convince them that learning is not just about the accumulation of Jeopardy answers but about learning from others to see the world as this complex and amazing place. Leavy’s novel achieves those multiple layers in a way that is welcoming and easy for a professor to use. Moreover, those questions and activities give us lots of options for teaching that connect students to the broader themes and larger questions.

Teaching with Low-Fat Love

“Casey bombed into town with her daily organizer.’” (Leavy p. 10)

The first time I used Low-Fat Love was in US History since Reconstruction, a General Education class aimed at first year non-majors. In short, every student must take it, and they do not want to. This second part of the US History sequence has a range of canonical texts that students rarely read but that told are “classics.” As a scholar of color, I am always suspicious of canonical texts, and texts labeled as classics because I am very aware of the exclusionary nature of academia and publishing. Moreover, the canonical texts in this area present an experience too divorced from the students reading it.

Even favorites like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) or Zora Neale Hurston Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) that are so evocative of their eras, offer so little that today’s students can recognize and thus connect to. There are benefits to using canonical texts such as the lower cost, the abundance of online resources, and the chance they may have encountered it in high school. But the one thing that seemed to link the books I used in this course was the fact that it was almost impossible to get students to engage with the stories even if they had read them (or the online summary). My journey to be a cool professor thus begins and ends with my desire to get the students to want to read because they know my choices will be both historical and awesome.

‘My journey to be a cool professor thus begins and ends with my desire to get the students to want to read because they know my choices will be both historical and awesome.

I’ve been using Low-Fat Love in my US History courses for years because of the ways it exposes the contradictions inherent in our outer and inner selves, and the journey to meld those parts together. Those contradictions begin with the title and cover, both things indicative of the lightweight and superficial, when it is are anything but. As Leavy writes in her preface to the Anniversary edition “Prilly lives in between who she is and who she longs to be.” This instantly connects the texts to the lives of my students, people existing in a space of transition, distracted and imprisoned in the ideas of their parents, popular culture and society at large about what their lives should be. Filled with potentiality, like the protagonist and those that surround her, the students can see themselves in explicit and implicit ways.

‘I’ve been using Low-Fat Love in my US History courses for years because of the ways it exposes the contradictions inherent in our outer and inner selves, and the journey to meld those parts together.

As a nerd, I figured knowing the author of the novel we were going to use would immediately give me cool points. But students are so cynical that they believed I chose it so I could make my friend some money! That made me laugh as I explained how little money people make from academic publishing but it did highlight the sad fact that their first instinct was to find a reason not to like the book their professor assigned. When I asked the students to bring the book to class so we could dispel their worries by reading the opening few pages, I distinctly remember one male student saying loudly enough to be heard up front that he didn’t understand why we were reading a “stupid romance . . . this isn’t a women’s studies class.”

There were so many things citizen Melissa would have said to that reductive misogynist statement such as “it’s not a male studies class either but we read material by men” but Professor me simply smiled and used it as the jumping off point for our first discussion. Since Curry College is in Massachusetts, we began in Dunkin’ Donuts, which took us down a rabbit hole of cultural imagery (the original cover to the novel featured doughnuts). Even the cover is worth talking about in an academic setting. It has definitely helped me see the importance of the covers for my own books. Get them talking before they even crack the cover. It definitely ensured a higher read rate than I would normally get.

Patricia Saves the Day. . . Virtually

As a former professor, Patricia approaches her role as famous novelist in a way that changed the trajectory of my teaching. Offering to attend class for free, she allowed the students a learning ability they had probably never imagined existed, the opportunity to talk to the author about their intents, meanings, and desires. Getting to see the author of the book they were reading as a real person completely changed their relationship with the work and their relationship with their learning. Having the author of the book you are forced to read is thrilling and helps release them from so many of the scary anxieties their Writing and Literature classes has instilled in them. What Patricia gave them was the right to believe their observations were valid and that they had the ability to understand the lessons she imparted.

She empowered them in ways that changed their relationship with literature and helped me get them to open up and use the novel as a jumping off point to talk about the contemporary world. They were able to see two friends step out of the scary professor box and chat about a novel one of them wrote while making broad free ranging connections. They heard from a mother with a daughter close to their age, who shared the ways she truly saw her and began to open up and share their stories of low-fat love and their thoughts on what they read. I guarantee that most of them read it and those who didn’t read it after they met her. Now I specifically choose my readings based on whether I can get the writer to class (and Zoom makes that easier).

A Mirror to My Soul

As a teenager, she admired the beautiful, popular girls. To her, they had been graced with the best gift of all: the gift of possibility. When you are beautiful, all you have to do is add on to that to get what you want, to be who you want to be. (p. 11)

Like so many passages in this novel, this moment resonated with me so hard I had to stop reading and check myself. Growing up, even today if I’m honest, I admired the skinny, popular, white girls. Their lives seemed perfect, their families were loud and happy, they were always busy at playdates, parties, and the movies, and I was not. Everything seemed so easy for them, and I based my self-loathing around the very real fact that I was not part of them because I was fat and ugly and Black.

That was just how life worked; everyone loved pretty white girls, as evidenced by the media images all around me and the ways they seemed to get all the positive attention in school. So, from a very early age I began to mark myself as different, to at least believe I had the power to create a skin I could live in. I was a rock goth who dressed in black, only listened to underground bands like The Smiths and L7, and consumed reams of horror, SyFy and fantasy.

‘...When you are beautiful, all you have to do is add on to that to get what you want, to be who you want to be. (p. 11)

I truly believed it was me; that I was born broken. But Low-Fat Love helps me understand that it’s not. Patricia’s insights, born of years of interviews with girls, coming so early in the novel are great doorways into discussion for my College students, sitting on the cusp of possibility, drowning in the fantasy given to them by the world in which they were raised. Each student, regardless of gender, could take that passage and unpack their response to it, either from the excluded position of Prilly or as one of “the beautiful, popular girls.” Since someone was narrating their experiences, they felt freed to open up in ways they never could when discussing a history ‘classic.’ Leavy created characters who felt like them, who are believable in their inner dialogues and behaviors, so that they, like me, were suddenly not alone and invisible.

Patricia’s insights, born of years of interviews with girls, coming so early in the novel are great doorways into discussion for my College students, sitting on the cusp of possibility,..

The first time I read Prilly’s core flawed belief, as with much of the incisive writing, I felt seen in a way that triggered my shame, as if Leavy was accusing me of something by making Prilly the way she was while offering insights about toxic beauty standards. Prilly’s thoughts were evidence of her failings and thus my own. As with good therapy, she opened a crack in my well-developed armor that placed the blame for my perceived failings at the door of nature rather than inaction. Since over thinking is my whole thing, that made me really think about how my students would react at an earlier point in their lives. But their conversations mirrored Leavy’s intent, “to engage students in serious discussions about self-esteem, identity, love, relationships, and the social construction of femininity in popular culture” (2016.)

Beautiful Famous People

More than any other celebrity, Angelina seemed to have it all. (p. 11).

The use of Angelina Jolie as example of our toxic need to consume fantasy celebrity lives connected with me because of my age, but also because of the ways in which Leavy tapped into the most famous couple of the day. “As Prilly watched the story she felt a familiar storm cloud of envy, longing, and self-loathing,” (p. 11) just as I do standing in line at the grocery store skimming headlines and pictures to see the ‘real’ lives of beautiful famous people. Of course the ultimate fate of “Brangelina” highlights the ways in which the lives we see are fantastical creations and that we can never really know what is going on in a person’s life, especially when curated for social media.

Today’s students are well versed in the idea that lives are curated online. They understand how many selfies it takes to get that perfect one you’re willing to post, and how the narration of their lives only contains the parts they are willing to publicize. Yet, at the start of any discussion, they (like me) have difficulty in connecting that knowledge to the person they are looking at. If it’s in print, our brains tell us, there must be some truth to it. Or they have become so cynical that they believe everything is constructed for public consumption to get more clicks/likes etc.

‘More than any other celebrity, Angelina seemed to have it all. (p. 11).

In one semester, we used Beyonce’s album Lemonade (2016) as part of the visual soundtrack for the novel in which she processes her husband’s infidelities, choosing to pursue her own low, fat, love. As we unpacked the public face of her relationship and dissected the lyrics, several students remarked that the affair had only been a media construction to help her sell an album.

Their evidence was the fact that she had stayed with JayZ and that the album had been so successful. If it had been real, or it had mattered, she wouldn’t have written songs about it and danced around in music videos. Each semester the jarring impact of their media literacy reflected the lessons about truth and fantasy they take away from it and Low-Fat Love forces them to consider and unpack their responses particularly the idea that celebrities somehow give up their humanity for fame and so are undeserving of empathy or compassion.

Public and Private Faces

“Low-Fat Love is a raw, honest, authentic, and compassionately rendered novel about appearance versus reality, the gap between who we are and who we wish to be, and the damage we do to each other and ourselves when we settle in life and love” (Laurel Richardson in Leavy, 2021, p.xi).

Each of the characters is a study in the difference between our public faces and our true ones that we may have hidden so well, we don’t even recognize the difference. But if, like Leavy’s characters, we are unable to see our true selves, then we are equally unable to ‘see’ anyone around us, instead we create fantasies about them that fit our own internal narrative. When Pete and Prilly have their ‘meet cute’ at a Jeanette Winterson book talk, she notices he “had striking teal eyes framed with a few soft lines that made her think, he’s really lived” (p. 25).

When she goes to his grotty little flat Leavy writes that “Normally Prilly would have been put off by such a scruffy little apartment, but on that night she saw the simplicity differently. He’s living like a real artist, she thought” (p. 28). I have had more than one love, unrequited and not, that functioned around a fantasy I had built in my head of the intense, poetic bad boy. Like Pete, they were usually far smaller and less interesting than I made them in my heart and the relationship relied on maintaining that fantasy.

Each of the characters is a study in the difference between our public faces and our true ones that we may have hidden so well, we don’t even recognize the difference.

Silence is not evidence of deep thinking, and condescension is not evidence of brilliance. In many cases, boys like that worked to make you feel smaller to match their own crippling sense of fear and inadequacy. Pete is frozen at the same moment as Prilly, the moment of becoming, but he is almost forty and his quest for that ‘big life’ has left him trapped in an aborted adolescence with dreams of becoming a great artist. Still clubbing with people who have stayed the same age while he’s gotten older and sadder, he shows my students the potential outcome of that seemingly cool student.

Both he and Melville are starters with endless reasons not to finish. It reminds me of one of my first loves who was achingly cool in a Trent Reznor way; but unlike Reznor he never grew up, just stagnated and declined like his fabulous long locks. Being essentially a bootie call seems like a great stand in for a real relationship when the guy is cool and talented and popular; just like a Dunkin’ Strawberry Frosted donut seems like a great stand in for lunch. That is until you’re left empty, ashamed, and a little sick.

Appearance Versus Reality

Janice Goldwyn prided herself on three things: her career, her family, and her house. More accurately, she prided herself on the appearance of her career, the idea of her family, and while she truly loved her house, she always feared that she best not get too comfortable there. (pp.32-33)

Leavy is constantly reminding her audience that you get the life you work for but that busy work is not the same as working towards a real ambition. Janice is a master of appearing busy without accomplishing anything. I too had mastered the art of busyness, surrounded by piles of incomplete work and task lists, I lived in the space of stress and too much work as my excuse to stagnate.

Hanging out with Patricia is a lesson in choices, understanding that you do what you choose to do, and the rest is just excuses. She gets up and lives an entire day floating from office to coffee shop with a clear plan for what she is going to accomplish that hour, that day, that week. She works breaks into her day, has a start point and an end point, and spends more time actually writing than complaining about all the writing she has to do. If you have no plan for your life, life still happens.

‘Leavy is constantly reminding her audience that you get the life you work for but that busy work is not the same as working towards a real ambition.

Moreover, while you might spin a fantasy about your career and the reasons for your success or failures, the truth is always there for people to see. “What Janice failed to realize was that although she was legitimately quite skilled at her job, she rubbed people the wrong way. The only thing standing in Janice’s way was Janice” (p. 34). While there are very real roadblocks to success and things you cannot control, what you can control is your role in your life and the ways in which you meet the world.

Janice is provided with great reasons for her disfunction and for her toxic relationship with the world, but it doesn’t absolve her or the weaknesses in her working roles. After allowing the lessons of this novel, and really seeing Patricia’s life through her goals and personality, I began my journey of recovery and of seeing and accepting my own light and responsibility for how I was seen and treated at work. At fifty I finally accept that I am a respected and liked colleague not just because being British makes me seem smarter and cooler, but because of the ways I have lived my life.

Using Novels and Television Shows in Classes

Prilly lived in between who she was and who she wanted to be. She had moved to Manhattan from Boston in search of a big life. She had always felt she was meant to have a big life. To date, at the age of thirty, she had barely lived a small life. (p. 11).

My U.S. History courses are fully integrated experiences so that students are exposed to all the tools that bring the past alive including novels, movies, and music. Each semester I get obsessed with a theme, usually inspired by one of the novels I intend to use, or a movie/play I had seen. The first time I used Low- Fat Love followed a semester where I had used Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 novel Fight Club and themed the course around masculinity, so I needed an intellectual palette cleanser.

That summer I had also discovered the show Girls (HBO 2012-17), which felt evocative of the world Prilly was trying to create and another version of Patricia’s love Sex in the City (HBO 1994-2004). Both shows presented ideals of white womanhood, separated by a generation. The women of Sex in the City (HBO 1994-2004) were all beautiful, thin, popular, and lived in one of the most exciting cities in the world. They existed in a world of privileged whiteness where they always knew what to wear, always found a man for their arm, and their biggest financial challenges focused around the cost of designer shoes.

‘The first time I used Low- Fat Love followed a semester where I had used Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 novel Fight Club and themed the course around masculinity, so I needed an intellectual palette cleanser.

If you were white, and middleclass, and female in the 90s, I’m sure shows like Sex in the City or Friends seemed fun and aspirational. For some of us, it was a weekly reminder of how cool it must be to be something that you will never be: white. But Girls was an even better fit for that semester because this was the other end of that story, when those same women first graduated College and went out into a world that was nothing like they had been promised. As we read the novel, we watched a few core episodes of the show to help visualize some of Leavy’s observations. The show is a far harsher look at the world juxtaposing and elongating some of the moments we see in the novel.

‘If you were white, and middleclass, and female in the 90s, I’m sure shows like Sex in the City or Friends seemed fun and aspirational. For some of us, it was a weekly reminder of how cool it must be to be something that you will never be: white.

Leavy gives us characters who don’t know how to make friends and have big exciting lives. Our protagonist knows what her life is supposed to look like thus it fills her with shame that her New York life is nothing like the life she watched on tv for so long. Prilly’s attempts to be cool are indicative of the problematic lessons we learn as we are becoming. Prilly doesn’t know how to make friends, how to be a colleague, or find a partner. Everything she learned came from examples of perfection, stories of people who floated through the world with the ease of people whose lives are only real in forty-two-minute blocks and whose problems are ultimately superficial and solvable.

Prilly cannot find a boyfriend, but the women of Sex and the City have one each week. They eat in cool trendy restaurants most nights, yet never seem to put on weight. They complain about money but always seem to have enough of it to do whatever they want including paying their bills in one of the most expensive cities in the world. Their unhappiness is never very real because they were beautiful thus their imperfect perfection made everything easy. But as the students will tell you, no one really knows, some people just have the self-belief to make their reality the best version even if it bears no relation to accepted peddled ‘normality.’ It’s the hardest thing to be who you are and not what you should be.

Faking a Big Life

The Internet dating ended up costing her $199, a weekend’s worth of screening time, one terrible evening, and an untold sum of shame. (p. 18)

Prilly’s search for the Big Life and a grand love made me laugh aloud and had far greater connection to my life than my students but extended the commentary about finding a “big life.” “Without many friends to go out with and no real effort made at dating, her life was fairly lonely. She decided to invest energy into her weekend routine. Convinced that if you lead an interesting life you will meet interesting people, Prilly made being interesting her full-time weekend occupation” (p. 19). I’ve been in endless Yahoo Groups for movies, and the opera, joined book clubs, attended glass blowing and jewelry making, gone to group sports events and joined every online dating app from e-Harmony to Silver Singles. I’ve turned off my phone and pretended I was busy on Valentine’s Day and Christmas.

For years I invented Monday morning stories about my weekend activities that made me seem exciting and dynamic and popular, when I was really lying on the couch watching a Stargate marathon for the fiftieth time or reading novels about destined soulmates who randomly find each other. As with the women in Girls and Prilly, I knew life was supposed to happen to me, and all I had to do was look interesting and things would come with little effort on my part. Prilly’s blind inaction is a cautionary tale for my students lest they end up like her or Hannah Horvath (Lena Dunham) instead of Carrie Bradshaw (Sarah Jessica Parker) or Rachel Green (Jennifer Aniston.)

College, Popularity, and Consent

He was afraid to even wonder what had happened to her behind closed doors, when she was intoxicated and perhaps unconscious. The truth was all-too apparent and all-too horrific. (p. 110).

The place where my students take over is in discussions of Tash and Kyle, who share their stage of life. These two cousins illustrate the impact of being parented by people who do not see themselves and thus can only see their children as extensions of their fantasy about themselves. Kyle, perhaps the only pure soul in the novel, often a favorite, provides a nice alternative to the dysfunctional characters around him. I’ll often have a student who has a Kyle in their lives, or the occasional student who gets outed as one. Of all the characters he is the ‘nice guy’ that is understandably everyone’s best friend, the one who is always there for them to pick up the pieces of a messy night.

The scenes with Tash and Kyle allow the students to both see and dissect their decision making in their first years on campus. Tash is often discussed as the girl who believes being drunk or high will make her likeable and popular, one of the in-crowd. Her choices are so familiar because they are born of the far more common desire to replicate the fantasy of College that excludes the very central ideals of safety and consent. It sounds great to say “I got so wasted last night I don’t remember,” but Tash’s great night out reflects an uncomfortable and horrifying truth for too many in the room.

‘…The truth was all-too apparent and all-too horrific. (p. 110).

It gives us a doorway to talk about the expectations of College, and the expectations of popularity for both male and female students. Kyle seems to have come with a greater sense of himself, an inner quiet confidence that allows him to just say no because he does not feel the need to become impaired to feel comfortable enough to fit in. Tash, on the other hand, appears loud and cool but like Prilly and Janice, is drowning in her insecurities and shyness so that she believes she is more interesting wasted. Whether students were able to talk about it or not, these two characters opened a doorway to talk about the different worlds of campus and the serious consequences of the lack of self-belief.

I’m the last professor to weave a myth about how all drugs are bad since that simply creates shame and shuts down open dialogue (and is not true). Instead, we end up in a discussion about consent and the social consequences of saying yes or no. I have no other novel that can open so many doorways for the students to welcome in the students through their own experiences and where they have something to teach. It builds self confidence and self belief that they can analyze literature and make critical connections to content creating bridges between their worlds and their studies.

Mind the Gap

It’s also a reminder that we can change the audio feed in our heads, we can reimagine ourselves, and indeed, we can remake our lives day by day. (Laurel Richardson in Leavy, 2021, p. xii)

Ultimately there are so many elements that demonstrate Leavy’s expertise in explicitly and implicitly drawing out the relatable truths at the heart of humanity in today’s world, while creating a story that feels incredibly intimate. But Leavy’s greatest talent is in writing stories that are for multiple audiences and we can read it at multiple levels from consuming it in an afternoon on the beach to doing a deep analysis in the classroom.

I’ve used Low-Fat Love in classes many times because of the way it resonates with the students in ways general historical material cannot, feeling accessible and thus understandable. It is contemporary literature at its best, accessible and incredibly well written, with prose that welcomes in a wide-ranging audience, short enough to consume quickly, but with enough depth to satisfy you. Its sociological issues are apparent yet not overwhelming. Its message is both useful for encouraging critical (deep) thinking, and potentially resonating in a college setting.

‘As she passed the teahouse, she smiled and replayed Melville’s written words in her head: Mind the gap. (p. 163).

One of my favorite moments when reading a text in class is to ask them who they would recommend the book to. Sometimes it’s framed around a person in their lives, or a room they might leave it in to be found by a type of person who would benefit from it. Remember that male student who complained about reading a novel by a woman covered in donuts? Well his response will always remain my favorite. He declared that he was going to “make” his little brother read it so he didn’t turn out like all the boys he knew wanting him to be more like Kyle than Pete. Then he was going to give it to his older brother who was struggling with his own love, fat, love.

If that young man could so transform himself with a little chick-lit novel, and was willing to share it with his peers, there is hope for us all. It’s why I will always use the novel to help them grapple with today and why they see the world the way they do. I lived too much of my life on a low, fat, diet that made me feel inadequate and unsatisfied. With Low-Fat Love, Patricia Leavy brought love and light into my life and classroom and now I gorge on a healthy full fat diet that energizes and sustains me.

References

Leavy, P. (2011). Low-fat love. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Leavy, P. (2021). Low-Fat Love: 10th Anniversary Edition. Kennebunk, ME: Paper Stars Press.

About the Author

U. Melissa Anyiwo is a Professor of History and Director of Black Studies at the University of Scranton with 20+ years’ experience. The focus of her career has been advancing the representation and inclusion of minoritized communities and individuals to aid expanding knowledge and understanding of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI). Her teaching includes the U.S. History and Culture sequence, where she regularly uses texts by Patricia Leavy to enhance and a range of Black Studies courses based in historiography often using the vampire as an inclusive pedagogy.

She has been using works by Patricia Leavy since 2012 including Low-Fat Love (2011), Film (2019), Spark (2019), and Re/Invention: Methods of Social Fiction (2022) to enhance her teaching. Melissa has published on inclusive practices including “That’s Not What I Signed Up For”: Teaching Millennials about Difference through First-Year Learning Communities” in Outside/In in Teaching Race & Anti-Racism in Contemporary America (2013) and “Using Vampires to Explore Diversity and Alienation in a College Classroom” in The Vampire Goes to College (2013). Finally, she starred in the WVIA Short “It’s More Than Hair” (2023), the Podcast Systemic episode “Policing Black Bodies” (2023) and the documentary “Lestat, Louis, and the Vampire Phenomenon” for the Interview with the Vampire 20th Anniversary Edition DVD (Warner Brothers, 2014).

Credits

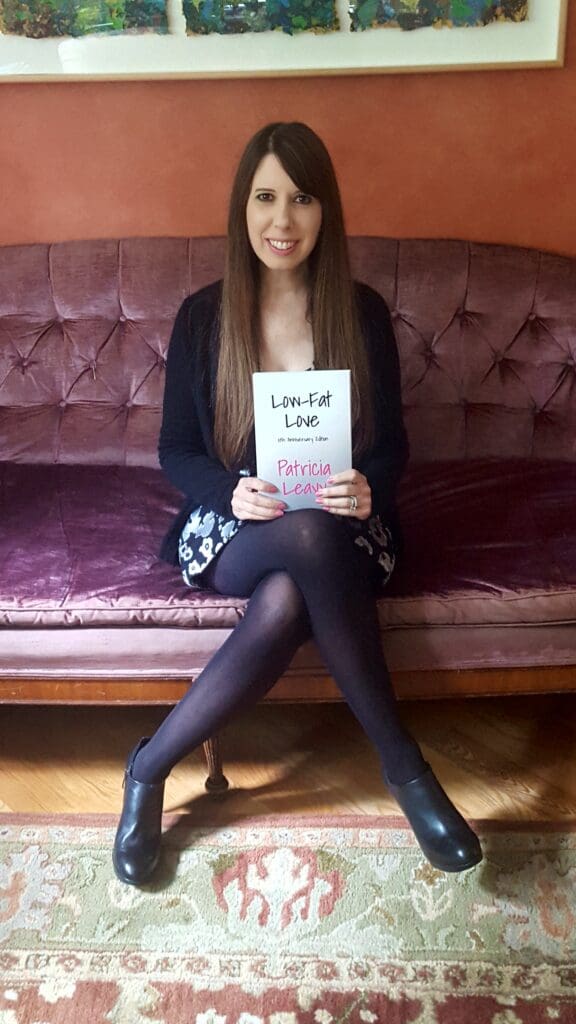

All images provided by Patricia Leavy

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.