American literature calls attention to the fragmented writer, the many hyphenated-American writers, whose stories connect and bind to the American experience.

I noticed my student perspiring, small sparkles noticeably collecting upon his forehead, and in that instant my blood retreated from my headspace into my chest. I wanted her to stop speaking to him; to protect him from this mindless assault upon his identity. It seems silly, hyperbolic, perhaps a bit banal. To think a white woman asking a Latino teenager what “he is,” to be anything other than innocent would be an exaggeration. He didn’t want to answer, and his eyes dashed to me.

This is not a story about my students, but rather it is about the word minority, and American literature rendering the word obsolete. It’s a simple word that is a sociocultural norm. The American-institution continues to thrive on it, marginalizing a majority, controlling by way of racial and ethnic paradigms, a continuity of the American dream: the American aesthetic. To be sure, most hyphenated-Americans like my student would have been comfortable celebrating their ethnic background, cultural identity, had it not been for the aforementioned paradigms. So what is the “majority”? Surely such a title belongs to one racial/ethic group, for there cannot be a minority without a majority.

No one answers, so I look to American literature. I cannot look to the demographic via the Census Bureau, because like my student, many people do not feel safe telling the truth. I do, but I am an assimilated American, third-generation Mexican-American, and I can safely take pride in it. I am not under constant threat of deportation, nor am I constantly harassed by a phantasmic difference between the American and the cultural sides to my identity.

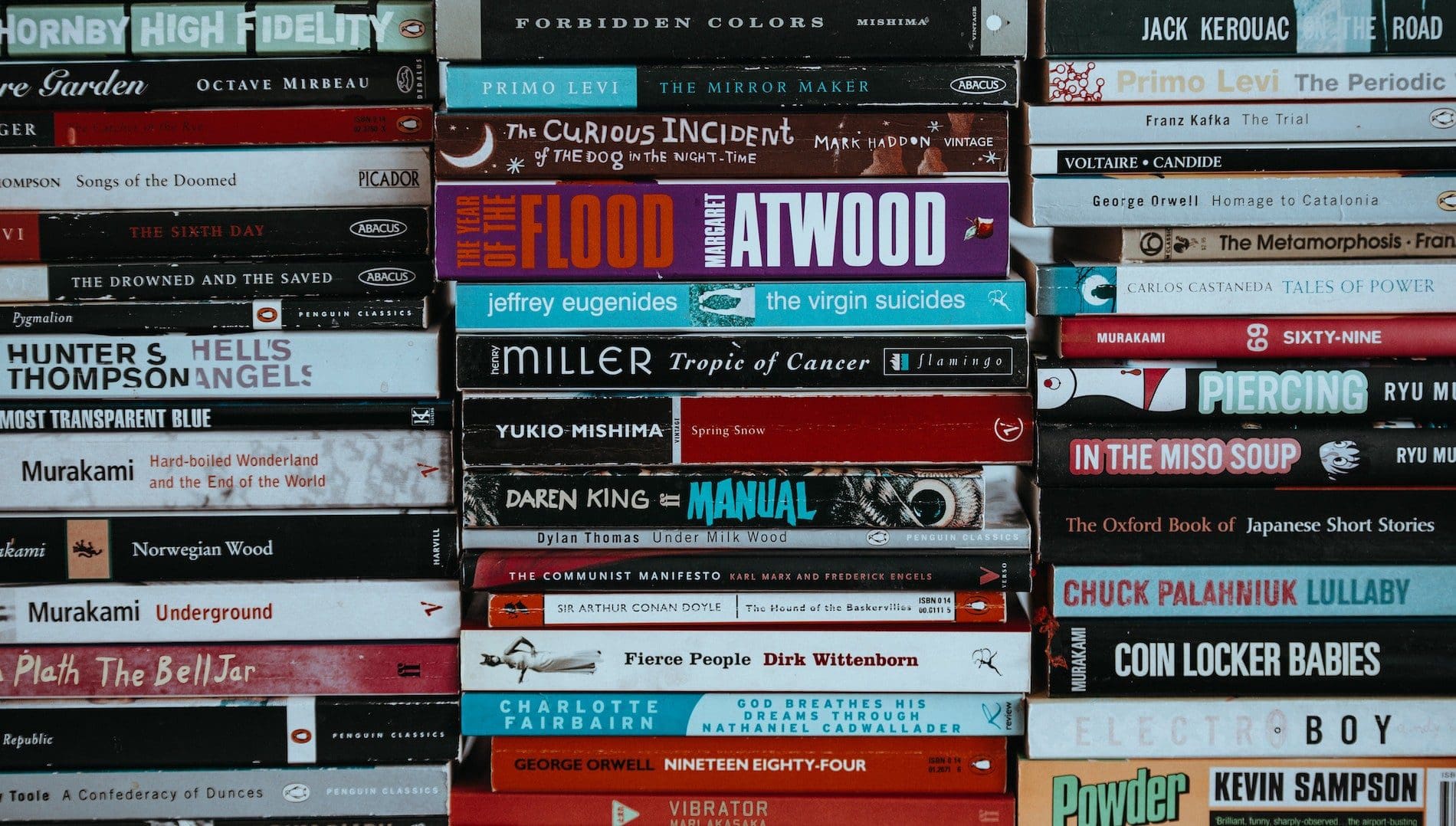

Literature will always tell us more than the polls. American literature calls attention to the fragmented writer, the many hyphenated-American writers, whose stories connect and bind to the American experience. For instance, as I studied American-Modernism in school I wondered what made it “American” other than the nationality of the writers. I scanned names like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and T. S. Eliot. I found much of Fitzgerald in France, Hemingway in Spain, and Eliot in England. Though I do enjoy them, I do not connect personally to these writers. I wondered what made it “American”. I never did get my answer. I find more of my American experience in African-American literature, Mexican-American literature, the hyphenated-American literature, the fragmented writers that are hyper-aware they are fragmented.

My experience sifting through the American literary canon has been a lot like my experience glancing around my classroom: The minority, (a term denoting to be less-than), has become the majority. A shift that many are blind to because the term minority is so integrated into society that it is keeping many, like my student, from celebrating their cultural identity.

As a high school English teacher I am called upon to teach “American” literature, Chicano literature, and African-American literature. For some reason that umbrella term, American Literature, is given as a title to some, typically white-male, writers. The American, the sole-American identity writer, has no designated ethnicity. The others are designated; half of one identity and half another. The rupture between the two identities began during the Reconstruction and the ever-expansion of the U. S., a process still occurring. One half of that identity, the American half, is machine. The other half, the ethnic half, is where the cultural traditions and ritual resides. It is not equal—as we find some American literature to be less rich in cultural background and richer in the mechanics of America. For example, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby centers on the American Dream; more machine, less cultural tradition or background. So, too, does David Foster Wallace focus much of his writing on the machine like his unfinished novel, The Pale King. This has little to do with race and everything to do with the process of ‘becoming’. It has to do with what the American person identifies with more, which half of themselves.

Some writers deal with the duality evenly, and such is the case with N. Scott Momaday’s House Made of Dawn. Again, one half of the American identity, as found in American literature, is machine and the other rooted in cultural or ethnic background. The importance literature has to its society is profound, able to change and shift outdated norms, if the writers exploit those norms. This exploitation has seemingly been an unconscious one. My experience sifting through the American literary canon has been a lot like my experience glancing around my classroom: The minority, (a term denoting to be less-than), has become the majority. A shift that many are blind to because the term minority is so integrated into society that it is keeping many, like my student, from celebrating their cultural identity. American is a land of fragmented people, fragmented writers, and it is in realizing that that I have a better understanding of the goings-on around me.

The diversity of the American literary canon deems the term minority obsolete, begging the reader to consider the racial/ethnic shift. The word is harmful, becoming structurally of a person’s identity, and only serves to divide children’s identities.

I have personally been that teenager, marking down “white” on a school application, hesitating to answer when an Anglo-American asked me “what are you?”, and leaving those experiences with a deeper sense of displacement. What I want most out of this acknowledgement is this: For Americans to open their eyes to the world around them. Read fiction, others experiences are probably not so far from your own. To stop imposing political machines upon our teenagers; for they are teenagers. And next time you think of the term minority, consider instead the people in your immediate environment. Consider those fragmented writers.

AUTHOR’S MEMO

While studying American literature it has dawned on me how closely it examines the complex sociocultural structures of our country. It’s also dawned on me that people of the modern age have lost touch with reading. However, it is contemporary American literature that calls attention to shifting racial and ethnic paradigms that people are blinded to because of social norms. I have studied the concept of minority in American literature with theory, shared my findings with non-academics, and have found myself totally opposed: It seems too complex or unrealistic. Autoethnography has aided in my ability to convey the concept of minority in a realistic way, because it is indeed realistic. In sharing my personal experience with complex concepts like becoming and minor, I am able to communicate the importance of the obvious realities around us that we are unable to notice or talk about. This article stands as a brief introduction to a much more complex and deeply interwoven concept within American culture: the minority/majority paradigm. This article was written in alignment with the theoretical frameworks of Gilles Deleuze, Michael Omi and Howard Winant. Deleuze theorized “minor literature”, a fresh perspective of minority and majority dynamics. Michael Omi and Howard Winant’s Racial Formation in the United States has been considered groundbreaking on the complexity of race and ethnic relations within the country. These works are not isolated to scholarship or academia, in fact they apply to the real goings-on in the world today and I urge readers of The AutoEthnographer to explore them and apply them to their own American experience.

Featured image by Annie Spratt on Unsplash