Editorial: On Social Fiction and the 2024 Special Issue of The AutoEthnographer

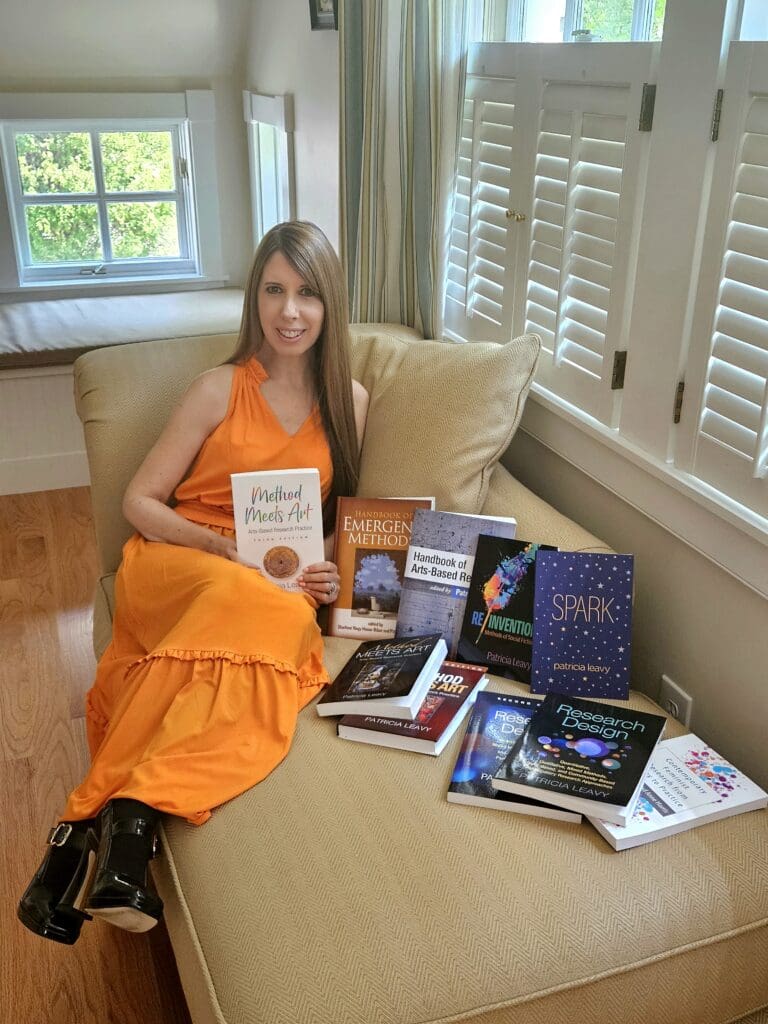

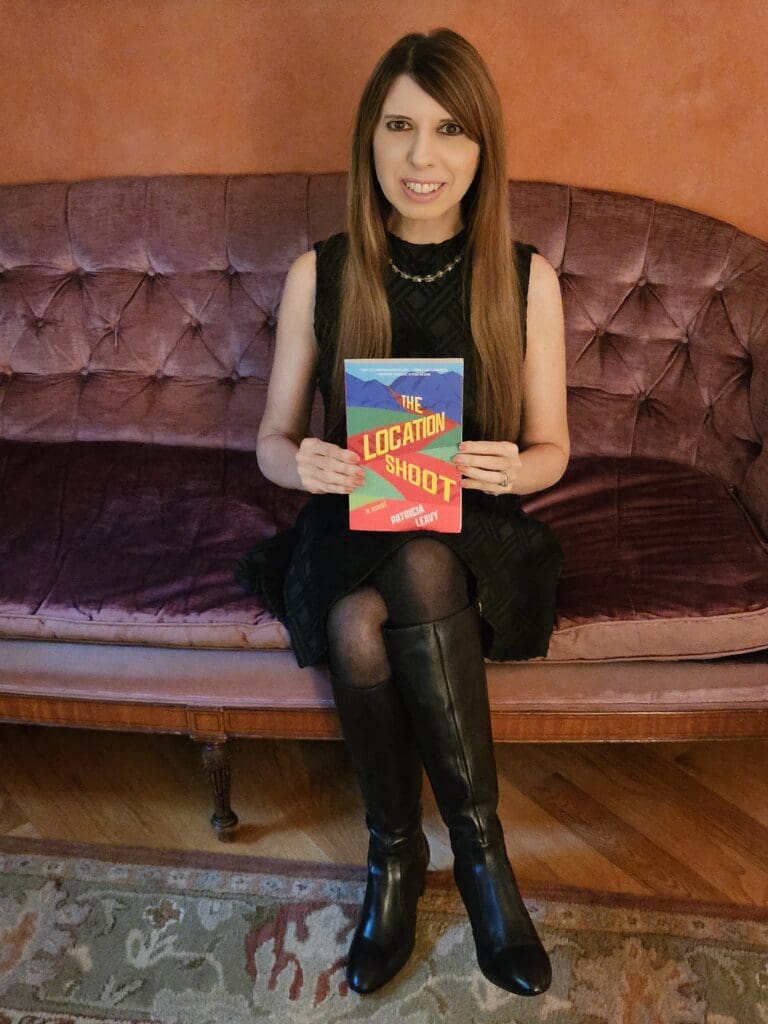

Patricia Leavy

My whole life is about words, and yet, words fail to capture how I feel as I write this editorial. I’m deeply honored and humbled that The AutoEthnographer has dedicated this special issue to celebrating my body of work. I’m profoundly grateful to the editor, Marlen Harrison, the managing editor Dilek İşler Hayırlı, the staff, and above all, to the contributors. When invitations were extended, everyone immediately said, “Yes.” Their generosity bowls me over. So does their creativity. While each contributor was tasked with covering a specific work or selected works, they were not told how to do so. They were given free reign. Their different approaches, perspectives, personal reflections, and artistry took over and I’m in awe of what they have produced. To me, this entire issue became a case of creativity inspiring creativity; stories inspiring other stories. They have certainly inspired me.

In contemplating the relevance of my work for the practice of autoethnography, perhaps what is most worth highlighting is my commitment to writing as a method of inquiry, my development of social fiction, and my fictional works. In the spirit of autoethnography, I’ll talk about these contributions in the context of my own life experience.

Writing as Inquiry

Much of my childhood was spent in story-worlds, reading, being read to, and writing. Story-worlds were magical—they transported me to different places where I’d meet new people, and learn about their lives in emotional, visceral ways. I could travel to story-worlds—to escape, hide, and dream. Creative writing was a refuge that allowed me to express things that were otherwise just out of reach. I could take my experiences and observations and mix them up with my fantasies, and suddenly have something that didn’t exist before. Possibilities. Infinite possibilities to explore and document life as I knew it, and life as I imagined it.

As an adult, I became a sociologist. I was still engaged in exploring human experience and trying to make sense of the world, and I was still writing, but traditional academic writing did not feel like infinite possibilities. It felt limited. Highly limited. As an academic I was trained that writing is something we do as we do something else—something bigger, our actual work. Writing is how we represent research, not how we “do” it. Over time I began to question this system, and to write on the borders of it. Eventually, I realized that writing is not an add-on and can constitute research.

Harry E. Wolcott noted that writing doesn’t merely reflect thinking, but rather, “writing is thinking (2009, p. 8).” Similarly, Laurel Richardson (2000) has explained that writing helps us discover what we think. Therefore, writing can be understood as a process of discovery. Writing can simultaneously be a method of inquiry and representation.

Social Fiction

In 2010 I coined the term “social fiction.” I had just finished writing my debut novel, Low-Fat Love. Truthfully, it was done on a lark. I was on sabbatical with extra time on my hands. Bored of traditional academic writing, I decided to work on something creative, just for a bit. For years I had collected interviews with women about their identities and relationships. They shared stories about low self-esteem, poor body image, depression, and unhealthy relationships.

Cumulatively, I had developed insights into women’s lives in the context of commercial pop culture. Insights I had no way to share. So, I took some of my jottings from over the years and decided to write something creative. Perhaps a poem. Perhaps a short story, I thought. By the end of the first day, I realized I was writing a novel. As much as it was influenced by my research experiences over a decade, it was also shaped by my own experiences, including toxic relationships.

When Low-Fat Love was finished, I didn’t know how to publish it. It was a novel that could be read by anyone for pleasure. It was also research and I hoped it would be read in the academy. How would I ever explain to a publisher, or anyone else, that it was both fiction and research? That question led me to the term “social fiction.”

What is social fiction? Social Fiction is fiction that is written by researchers in any field and reflects their scholarly research or expertise, often cumulative insights, and may also reflect their personal experience.

Bored of traditional academic writing, I decided to work on something creative, just for a bit. For years I had collected interviews with women about their identities and relationships. They shared stories about low self-esteem, poor body image, depression, and unhealthy relationships.

Social fiction differs from “faction” which refers to fiction inspired by real events, or a mix of facts and fiction, a highly ambiguous genre that requires no expertise on the part of the writer. Social fiction is also broader than “autofiction” which refers to autobiographical fiction. Authors should use whichever categories they feel best suits their work; however, I caution these categories can be problematic and there are specific issues that may arise (legal, ethical, personal). That’s a broader discussion that I take up elsewhere.

How does social fiction differ from traditional fiction? It’s about intent and perspective. Rebecca Hussey (2021) wrote an article about philosophical fiction which she suggests “deals with ideas in a direct way.” She explains that philosophical fiction purposely provokes readers to contemplate big questions. Similarly, Ash Watson (2021) suggests that sociological fictions “intentionally engage with sociological foci and ways of thinking (p.5).” She further explains sociological fiction explores sociological understandings and is grounded in sociological knowledge (Watson, 2021, p. 6).

Social fiction differs from “faction” which refers to fiction inspired by real events, or a mix of facts and fiction, a highly ambiguous genre that requires no expertise on the part of the writer. Social fiction is also broader than “autofiction” which refers to autobiographical fiction.

While some suggest that the idea of social fiction is new or radical, there’s a long and illustrious history of merging scholarship and fiction. Some of the most acclaimed scholars have used fiction to espouse their ideas, such as Simone de Beauvoir, Zora Neal Hurston, and Jean-Paul Sartre, all of whom wrote many plays, short stories, and novels. Sartre won the Nobel Prize for the very kind of work I call “social fiction.” W. E. B. Dubois also published fiction, including a romance novel, a genre in which I love to write. There are entire genres that could be understood as social fiction. Consider historical fiction and philosophical fiction.

By creating the term “social fiction” my intention was to house all the literary writing scholars have long done and will do. I’ve detailed the practice of using fiction as a research practice or “social fiction” in numerous books, chapters, and essays. My recent book Re/Invention: Methods of Social Fiction provides a comprehensive review of social fiction, from its historical origins to adapting literary tools and structure to publishing this work.

My Story-Worlds

There’s nothing I’m prouder of than my novels. I pour my heart and soul into each one. What’s my motivation? I create story-worlds so that I can crawl into them, and others can too. Sometimes when I need to work through something in my own life, I write a novel to help me.

The story-worlds I create aren’t always so happy. People suffer. They may be lonely, depressed, grief-stricken, recovering from trauma, assault, or abuse, or they may simply be at a crossroads they don’t know how to deal with. I find as I crawl through the stories I get to a different place. So do the characters. Perhaps readers do too. At least I hope so.

In recent years I’ve become obsessed with writing feel-good romance novels. I’m proud to use my voice that way. I’m proud to write novels in which people treat each other well and aim to live with passion and creativity. Romance is a genre saddled with biases. It’s often undervalued. It’s no coincidence that this is a genre dominated by women, both writers and readers. While I’m not one for labels, romance novelist is one I wear proudly. I’m grateful to put love into the world. Something we always need.

There’s nothing I’m prouder of than my novels. I pour my heart and soul into each one. What’s my motivation? I create story-worlds so that I can crawl into them, and others can too. Sometimes when I need to work through something in my own life, I write a novel to help me.

Many of the story-worlds I create are filled with creativity, hope, and love. Magic abounds. Writers, artists, publishers, scholars, and other creatives run across the pages. People in extraordinary pain are able to love others in extraordinary ways. These characters are aspirational. They model what real and lasting love might look like and feel like. They remind us that the relationship we have with ourselves is the most important. After reading one of my novels someone said, “I don’t know if I know any people that kind.” I said, “The question is: Are you that kind?”

Writing fiction allows me to document reality and to reimagine it, just as we can always reimagine ourselves. And that is why we need story.

Writing fiction allows me to document reality and to reimagine it, just as we can always reimagine ourselves. That is why we need stories.

An Invitation to Story

Everything in my life has shown me that stories matter. Sharing stories matters. Through stories we generate connection, resonance, empathy, reflection, discovery, learning, change, resistance, visibility. Storytelling is at the heart of my work. It’s also at the heart of autoethnography. I hope when you read my books and the contributions in this special issue that you’re inspired to think about how you might tell the stories of your research and your life.

References

Hussey, R. (2021). 20 Great Works of Philosophical Fiction. www.bookriot.com/best-philosophical-fiction/

Leavy, P. (2011). Low-Fat Love. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Leavy, P. (2021). Low-Fat Love: 10th Anniversary Edition. Kennebunk, ME: Paper Stars Press.

Richardson, L. (2000). Writing: A method of inquiry. In Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds)

Handbook of qualitative research 2nd edition. pp. 923-948. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Watson, A. (2021). Writing sociological fiction. Qualitative Research. pp. 1-16.

Wolcott, H. E. (2009). Writing up qualitative research 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Patricia Leavy

Dr. Patricia Leavy is a bestselling author, independent sociologist, and internationally known arts-based researcher. She has authored, coauthored, and edited over 40 books, earning critical and commercial success in both nonfiction and fiction, and her work has been translated into numerous languages. Her work has garnered a slew of book awards including USA Best Book Awards, Independent Press Awards, International Impact Book Awards, National Indie Excellence Awards, International Book Awards, New York City Big Book Awards, Firebird Book Awards, and American Fiction Awards. Recently, her novel The Location Shoot won a 2023 Literary Titan Gold Book Award for Fiction.

She has also received numerous career awards including, the New England Sociological Association 2010 New England Sociologist of the Year, the American Creativity Association 2014 Special Achievement Award, the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry 2015 Special Career Award, the National Art Education Association 2018 Distinguished Contributions Outside of the Profession Award, the American Educational Research Association 2018 Division D Significant Contributions to Educational Measurement and Methodology Award, and the American Educational Research Association 2022 Outstanding Achievement in Arts and Learning Award. She has also been honored by the National Women’s Hall of Fame, was presented an Award for Leadership and Humanitarian Efforts in Literature and Publishing by We Are the Real Deal, and in 2018 SUNY-New Paltz established “The Patricia Leavy Award for Art and Social Justice.” Dr. Leavy lives in Maine with her family. She loves writing, reading, watching films, and traveling.

Website: www.patricialeavy.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/WomenWhoWrite/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/patricialeavy

She Writes Press: https://shewritespress.com/portfolio/patricia-leavy/

Guilford Press: https://www.guilford.com/author/Patricia-Leavy

Credits

All images provided by Patricia Leavy

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Dr. Patricia Leavy is a bestselling author, independent sociologist, and internationally known arts-based researcher. She has authored, coauthored, and edited over 40 books, earning critical and commercial success in both nonfiction and fiction, and her work has been translated into numerous languages. Her work has garnered a slew of book awards including USA Best Book Awards, Independent Press Awards, International Impact Book Awards, National Indie Excellence Awards, International Book Awards, New York City Big Book Awards, and American Fiction Awards. Recently, her novel The Location Shoot won a 2023 Literary Titan Gold Book Award for Fiction. She has also received numerous career awards including, the New England Sociological Association 2010 New England Sociologist of the Year, the American Creativity Association 2014 Special Achievement Award, the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry 2015 Special Career Award, the National Art Education Association 2018 Distinguished Contributions Outside of the Profession Award, the American Educational Research Association 2018 Division D Significant Contributions to Educational Measurement and Methodology Award, and the American Educational Research Association 2022 Outstanding Achievement in Arts and Learning Award. She has also been honored by the National Women’s Hall of Fame, was presented an Award for Leadership and Humanitarian Efforts in Literature and Publishing by We Are the Real Deal, and in 2018 SUNY-New Paltz established “The Patricia Leavy Award for Art and Social Justice.” Dr. Leavy lives in Maine with her family. She loves writing, reading, watching films, and traveling. https://patricialeavy.com.