Some poems are so easy. They glide off the fingers, off the mind like a smooth wave. Others are so so hard to get down, even the specks of the images or words. There are poems that I’ve clearly been marinating on for a long time and so once they make it onto the page, they are there, fully formed, like Athena out of Zeus’s head! But others, whew. They are work and work and struggle and wrestling.

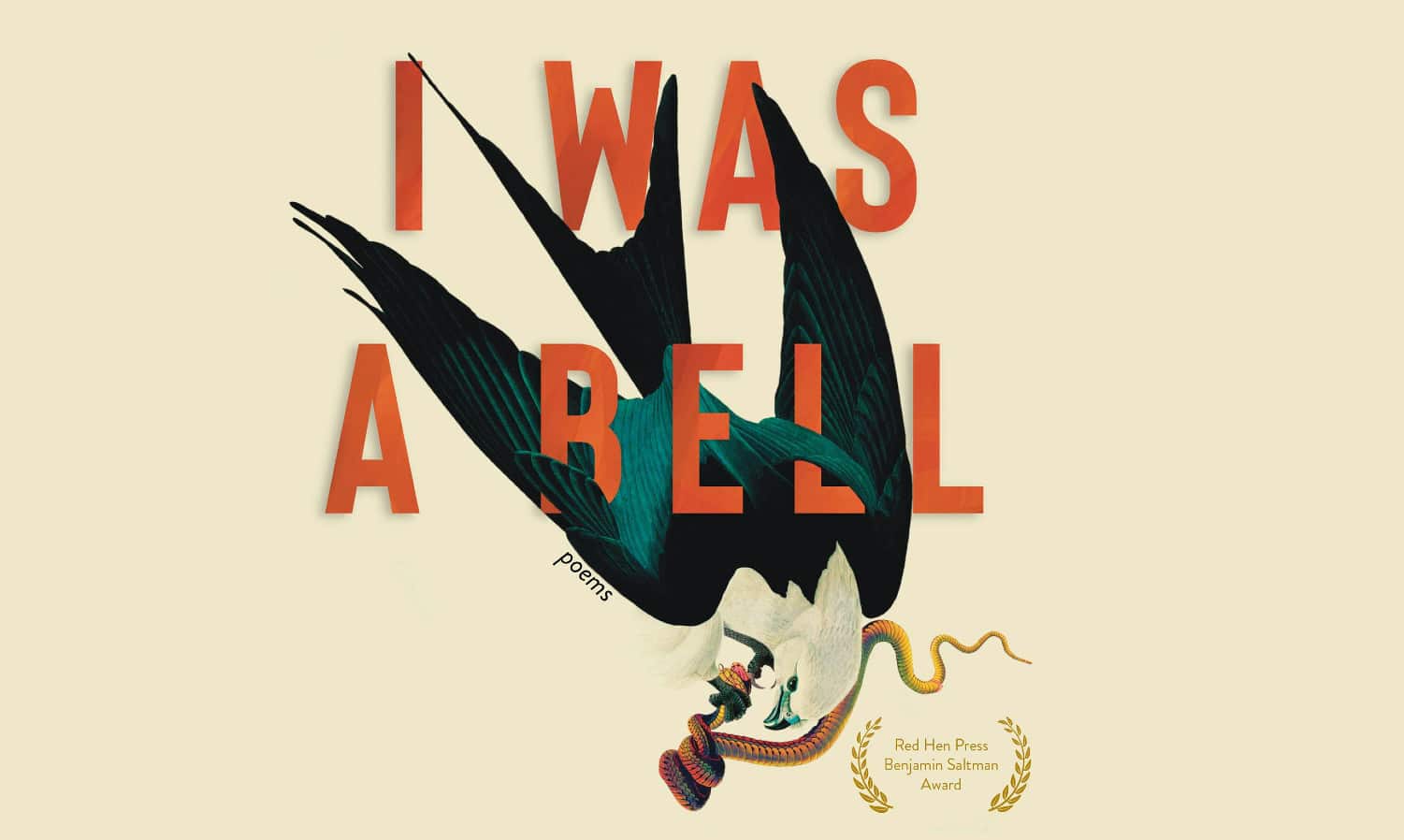

M. Soledad Caballero is the 2022 recipient of the International Autoethnography and Narrative Inquiry (IAANI.org) Best Book award for her poetry collection, I Was a Bell.

MARLEN HARRISON: Soledad, when we consider your new 4-part poetry collection, I Was a Bell, in its entirety, what is the story it tells?

M. SOLEDAD CABALLERO: This collection has a few threads that in my mind are all linked together. First and foremost this is a collection that thinks about memory, what we remember, what we think we remember, and how memory is a fluid and flexible thing. I work with a cognitive psychologist in my scholarly work, and I’ve learned about memory and its processes from this collaboration.

Memory is flexible because every time we remember something, it’s reforming the memory, it’s new. I really love this idea as a way to think about my collection which is about remembering my time in Chile, immigration, and then what cancer as a memory has done in my body, what the body remembers.

So, I guess I’d say the story is really how we thread any story together as a memory, but for me this collection is about opening up the idea that memories are static or stable. This collection is a way for me to think about weaving threads together that are going to be rewoven all the time anew. I also think of memory as a collective endeavor, like how re-membering, putting something together again, maybe something hard or difficult, can be a way to heal.

My husband and I read poetry aloud to each other and I know I’m in something like magic when I actually gasp at the end of a poem. Maybe that is what poetry is for me, the gasp of breath, of being aware that I’m breathing.

MARLEN: What has your personal experience with poetry been like throughout your life? Have you always been a writer and reader of poems?

SOLEDAD: This is such a great and hard question to answer! I think, at the end of the day, yes, I have always loved poetry, been connected to poetry, from the time I have memories of what poetry might be.

As a kid, my mother liked me to memorize poems in Spanish and I’d recite them at family dinners or other gatherings. I don’t remember the words to those poems, but I recall the feeling of the words in my mouth and the sounds in the room. I think my mom is actually a poet, though she would never call herself one. From stories of her own childhood, she’s told me about how her father would have these word play games, making up silly words, punning phrases, singing silly phrases as a family etc. And her father was also a musician, a guitar player, which is really a connecting of sound and words, I mean, what are poems if not songs, right?

And then when I had to learn English, I became really obsessed with knowing and learning it completely. And I always thought growing up I’d missed out on some essential way of really being fully in English.

I think poetry, reading it, writing it, studying it has made me aware of the fact that there’s not ever a “learning it completely” when it comes to language, and that reality is what is so beautiful about poetry. There’s always more to read and learn. I think of poetry as sacred; it’s been there for me in moments when I didn’t even realize I needed it.

My husband and I read poetry aloud to each other and I know I’m in something like magic when I actually gasp at the end of a poem. Maybe that is what poetry is for me, the gasp of breath, of being aware that I’m breathing. Audre Lorde has taught me that poetry is not a luxury, that’s her phrase. I don’t think I’ve really connected this idea of poetry to my gasping aloud at a poem that moves me, but it’s so connected! We need breath, and that’s how I think of poetry, as breath.

I feel like a rush, like “yeah, yeah I gotta try and grab that image, that bit of fire.” It feels very exciting and unnerving, because there’s always that sense that I’ll only ever grab a shadow of the image or idea. I’m always trying for the gasp, you know?

MARLEN: When did you realize you were a poet, and how has the experience of creating poetry affected you? Why poetry as opposed to other forms of creative expression?

SOLEDAD: To be honest, I sometimes still struggle to think of myself as capital P Poet! I think of myself as a writer, or as someone who writes poetry, that feels more manageable! When I was a kid, maybe in 3rd grade, I wrote a haiku and it was published in our little holiday book for parents (I could be misremembering this!) and that was the first poem I remember thinking of as something I wrote. But I didn’t think of myself as poet then either. So, I guess I am a poet but I do have a bit of imposter feelings about that word.

Creating poetry feels like a mystery to me, even now after I’ve published a first book and I’ve got the draft of a second one fully written. I think when I’m the midst of working on poems, on writing, I don’t think of it in a big picture way. Writing poetry affects me in very immediate and material ways and it’s always on my mind, a turn of phrase, a sound, an image just right outside of being fully conceived. When I’m in that space, I’m not thinking about the whole thing, just a line, a moment, a spark. And it affects me because I feel like a rush, like “yeah, yeah I gotta try and grab that image, that bit of fire.” It feels very exciting and unnerving, because there’s always that sense that I’ll only ever grab a shadow of the image or idea. I’m always trying for the gasp, you know?

I think I write poetry because it’s what I hear inside, how I make sense of the world. I’ve always wanted to try for other artistic mediums too. I have taken several photography classes because I want to try and link an image to the verbal images I try for. But I’m such a silly perfectionist, I get really frustrated in photography, which is a really ineffective way to approach photography. I’m planning on picking it up again this coming summer and really giving photography and its craft the attention it demands. In terms of poetry, though, I really love ekphrastic poetry, that is responding to paintings and other visual mediums via poetry.

I do so much research sometimes that I get lost in it and I love that feeling. I know sometimes people don’t realize how much research poets do, but we really do a lot because poetry is so relational, an outward expression, an attempt to communicate. So, research for me is essential.

MARLEN: As a poet, please tell us a little bit about your creative process. For example, you might touch on any or all of the following: how do you decide on a subject for a poem? Which subjects most inspire you? How do you go about composing your poems? What tools do you use for inspiration or in creating the poems? How do you know when a poem is finished?

I always feel a little nervous answering a question about my writing process because it’s a completely erratic, unsystematic process. Except for the research once I’m fully in a poem or set of poems. With research I’m simply obsessive. I read and read and read. I do so much research sometimes that I get lost in it and I love that feeling. I know sometimes people don’t realize how much research poets do, but we really do a lot because poetry is so relational, an outward expression, an attempt to communicate. So, research for me is essential.

Usually, poems emerge as images or a set of phrases and sounds. My poems are often inspired by a flash of a thought, the image, the phrase, or the memory of something, it’s a shadowy process sometimes. Often, it’s when I’m immersed in others’ poems and writing that my own writing emerges. There are moments of real joy but they are also uncertain moments since they are not fixed or clear to me.

Then the writing starts and that first draft is a lot of effort. At time it feels very physical, like I’m doing a lot of physical work. So I write many many first drafts in this way.

And then I let them sit for a while. I try to forget them, unless I still think there’s something emerging that I haven’t quite captured in that first draft. Some poems are so easy. They glide off the fingers, off the mind like a smooth wave. Others are so so hard to get down, even the specks of the images or words. There are poems that I’ve clearly been marinating on for a long time and so once they make it onto the page, they are there, fully formed, like Athena out of Zeus’s head! But others, whew. They are work and work and struggle and wrestling. They go through so many iterations. I have a folder called ‘extra stuff’ and there they are, these orphaned bits, some of them are like a decade old.

The other thing I do is write phrases, lines, images I think about as I’m walking through my day. They are mostly half thoughts. Sometimes they get to the page, sometimes they’re just part of the soup of writing. Like I said, my process is messy and erratic.

After this book, or while I was writing this book and getting it to its final form after it had been accepted, I was working on a lot of other poems. And I now have a second book in rough draft form. But doing the book readings and promoting for this book, plus my full-time job makes it hard to immerse myself in the revision of this second book. So that will come maybe in the winter. I like winter as a seeping and revising time.

There’s no all-encompassing immigrant culture, but there are those experiences of immigrants who have some knowledge and memories of a first culture and language and then who were thrust into and then lived in a second cultural and linguistic context that I think my book definitely engages with.

MARLEN: Culture can be loosely defined as “the languages, customs, beliefs, rules, arts, knowledge, and collective identities and memories developed by members of all social groups that make their social environments meaningful” (asanet.org). Autoethnography is a cultural research method where the researcher is also the participant because he or she has important lived experience that offers insight into the culture in question. As such, many creative people are actually autoethnographers because their work reflects on lived experience, and lived experience is always a product of cultural experience. Which cultures do you draw from or influence your writing in I Was a Bell?

SOLEDAD: Certainly, my memories and experiences are deeply implicated in how I enter and know the world and worlds I participate in and (hopefully) contribute to. I don’t think there’s one way or culture of being an immigrant, but that experience of knowing and feeling, at times, bifurcated is a primal way, or a mode of cultural knowledge that I’m thinking about in the book. There’s no all-encompassing immigrant culture, but there are those experiences of immigrants who have some knowledge and memories of a first culture and language and then who were thrust into and then lived in a second cultural and linguistic context that I think my book definitely engages with.

I first encountered this idea of the 1.5 generation when I was reading Gustavo Pérez-Firmat’s book Life on the Hyphen and it resonated with me. The 1.5 generations remember both spaces, the first space of home, language, images and smells, and then the migration and then the new space of home, language, images, smells – they are both there so there’s a real sense not just of memory but of having actually created some memories. I don’t know if that’s a culture, but that idea of a 1.5 generation immigrant is definitely something of a culture this collection engages with. I think also the culture of being bilingual but not equally so in both languages. And then there’s being of that generation that knows things happened in Chile in the 1970s but we didn’t live through them exactly and there’s a lot of silence around that history. I am also deeply aware that I am an American, Chilean-American, immigrant, Latinx yes, but also American. And I have been schooled in the myths and violences of this country, really deeply schooled and made by them. I mean, I am an academic, that is such a specific cultural context to write out of and through.

I’ve already resisted that scholarship is not creative and poetry is not part of my scholarly self. I think the idea of autoethnography allows for that cultural divide between the creative and academic to be really disrupted.

MARLEN: How do you see your work as autoethnographic? How has creative-expressive investigation of culture offered new insight into your own lived experiences? Vice versa?

SOLEDAD: I have to say I would not have known to think of my poetry as autoethnographic, but the sense of being both a participant and also a researcher of the traditions I write about, I could see that being an interesting and worthwhile designation to continue exploring. I like this fluidity between the scholarly approach and the creative approach to a topic. I’ve already resisted that scholarship is not creative and poetry is not part of my scholarly self. I think the idea of autoethnography allows for that cultural divide between the creative and academic to be really disrupted.

I think studying poetry has made me more aware of how much of living is the reliving afterward, if that makes sense. Or alternatively, how anticipating something, so the anticipation of thinking about a poem, the process of writing the poem has made me more aware that I’m doing the living in those moments that seem completely quotidian.

Since writing more consistently in this vein, a poetic vein, I’ve actually felt much freer in my more academic writing and that has also affected my teaching in really wonderful ways. I used to think and I was trained to think about this great divide between the thinking and the feeling selves we craft, and I’ve come to really value and try to live in a more holistic way that doesn’t deny the rationality of feelings or the irrationality of supposedly objective thoughts, if that makes any sense. I think mostly, I’ve tried to become more tender with the world and myself. Thinking about my past, my parents, Chilean politics, cancer, that has been a very vulnerable process for me and I think a benefit of that is that I’m less closed off. Or I’m trying to be less closed off.

I’ve also tried to rethink how I read anything. I am much more aware that when I am reading, I am really living not just reading about others living. There’s a desire in the culture of academia to divide praxis from theory, but the work and living I’ve done to get this book into the world has really shaken any sense that these are not intimately made from the same thread.

I think the best practices of writing poetry are about paying attention and listening for the underground sounds. I struggle with that because I get caught up in the grind of things and forget the sounds beneath those things. So poetry is a way to practice listening for the things that are not obvious but are very vivid.

MARLEN: Autoethnography has often been discussed as a process/product that explores the more challenging, complex, or difficult emotional experiences. I’ve often heard poets describe their work similarly. Can you speak to the emotional journeys of crafting I Was a Bell as both process and product?

SOLEDAD: Thinking of writing this book as a mode of having traveled through things but with few road maps is a good way to talk about this book! It definitely had a frame of a before and after cancer. And that divide is something I still think about and struggle with. So that journey of being sick and then what poetry allowed me to think through while sick is definitely part of the emotional journey.

Another vector of this journey was having to think about being a girl in a different space and in a different language. Sometimes in the middle of days, I still ask myself, would my grandfather know me now? And that’s this short hand way of asking, how would be different if we had stayed in Chile? That question is one I think about a lot. I don’t have a sense of being a good or bad question, it’s more like a process question – I know my experiences have made me this person now and I’d be a different person if there were different experiences, so it’s more of a checking in with myself question, and that checking in is usually rooted in things I’m writing about that are hard, or that I am still not sure I have any clarity about. I don’t actually want my poetry to be about trauma at all. I sometimes describe this collection as a love story to memory – the messiness is what is beautiful and worth thinking about.

This next collection I’m working on is more deeply connected to thinking about love. I’m trying to write love poems about being a middle-aged, fat, immigrant, having had cancer academic woman. Not sure how that’s going to turn out, but it turns out the shadows of love are as beautiful as the fully sun-soaked parts. I had this moment when the book was released when I realized, ‘oh god, people may read this book!” It was very unnerving! But poetry is a method for me of thinking about what I love and what I want and how and who I love and want. And that is a way to think about life, and life is, well, many wonderful but also hard things.

I think the best practices of writing poetry are about paying attention and listening for the underground sounds. I struggle with that because I get caught up in the grind of things and forget the sounds beneath those things. So poetry is a way to practice listening for the things that are not obvious but are very vivid. That is a great practice to enact right now when so many things are just quick blips of sound and light and then are forgotten. I think creating poetry forces me to be very honest about stopping, about really looking around, about paying attention to things. I think that is a great start to any kind of movement toward understanding and celebrating culture. I also think poetry in my life helps me remember that I am not the center of things. I think reading poetry and writing it, just being immersed in it, is a way to look past the self, to look past myself to things and ideas well beyond me and my knowledge and approach to things.