Redemption By Fire: The Remains of a Same-Sex Love

“Redemption by Fire: The Remains of a Same-Sex Love” poses spiritual debate on the process of interment. It constructs moral and ethical representations of secular and sacred thought through the consciousness of choice.

I lost my partner of twenty years to cancer. Jim’s death further magnified in emotion with the expression of disparate points of view regarding Jim’s final disposition. Family and friends endorsed a separation and scattering ritual while I subscribed to an alternative position without compromising a philosophical essence interpreted by Catholic religious doctrine. My decision esteems Jim in the integration of a sacred reality manifested in faith. Family and friends venerate an understanding of death through the ritual of sundering while maintaining a familial alliance for temporal freedom. Death, as a process and the pragmatic matters that follow it, establishes circumstances that are as much intimately personal as they are publicly universal.

In “Autoethnography: An Overview,” authors Ellis, Adams, and Bochner approach the engagement of autoethnography as a literary method that, “seeks to describe and systematically analyze personal experience in order to understand cultural experience.” This narrative evokes and allows identification to interpret my personal experience with the death of my partner and its impact as it connects to the trials and tests characteristic of all human existence. Cultural traditions associated with death vary. However, most agree that there is the representation for a transition to some other form. This realm is construed through subjective capacities who imagine God’s existence or non-existence. Decisions regarding burial and cremation, and who makes these determinations, can cause conflict in the name of belief and disbelief. Differences in opinion, all justified, sometimes welcome the surviving partner with displacement when there is no legal proclamation acknowledging the durability of their emotional union. Family and friends can absorb themselves in a myriad of reasons to contest wills, final dispositions, and a host of residual dealings in the aftermath of the death of their relative. This supports a strong argument for same-sex marriage to thwart legal headaches. Gay marriage has become acknowledged and sanctioned as a cultural phenomenon because of the accomplishments merited by LBGT. In my case, the vacancy of a ceremonial union with Jim permitted family and friends collaboration in the decision-making of final resting matters for him.

The autoethnography of, “Redemption by Fire: The Remains of a Same-Gender Love” compels the narrator to enfold cultural beliefs through a search for blind truth about the eternal. Death becomes the catalyst in the endeavor to comprehend the ineffability of the body evolving into spirit and the darkness of a lost love that remains.

(For Michele Christon who took the time to listen to my sorrow)

Redemption By Fire

Strong Son of God, immortal Love

Whom we, that have not seen thy face,

By faith, and faith alone, embrace,

Believing where we cannot prove…

Alfred Lord Tennyson

In the days that followed my partner’s death, I found myself sequestered in a daily resignation to tears. Jim’s passing was the end of the warmth, intimacy, and companionship I thought would sustain me into old age. My despair locked further as I pursued resolution.

Family Circle Meets a Male Union

The subject of Jim’s cremated ashes became the center of gravity. It attracted a pull in the strained direction of divergent points of view. Jim’s family and friends, my devotion to Jim, and Jim’s immortality all mingled in a consuming consideration. Jim’s relatives and friends offer advice in sobering voices of care. Some profess Jim’s cremated ashes to be separated and spread in various locations around the country where his siblings reside. Others consider the totality of his ashes also to be divided and diffused, not as a ritual in disparate geographical locations, but fittingly, over his parents’ grave: “It’s the right thing to do,” “It would be like still having Jim around us,” and “Jim is free from pain now” resonate in the decorum of the family’s solidarity and remembrance. However, I remain in the preoccupation of an alternative. It is a decision that savors the permanence of the well-being my twenty-year relationship with Jim brought me.

The family’s proposal to separate and spread Jim’s ashes articulates as an authentic requiem merging heart and mind. Yet, this ritual is at odds with my customary spiritual makeup because the symbolic essence behind Jim’s ashes deposits in a distortion. In the commitment of a male partnership, the situation answers to an identification of something that carries graver importance.

Those Biblical observations on death and eternity I paid attention to as a child with my hands folded during religious education classes hang over me like a troubled bird methodically discerning uncertainty. I want to stave off any expressions or gestures of betrayal. So, the family’s recommendation makes me densely uncomfortable. I find myself in a stoic confusion. My gut feeling tells me that it skews an introspection on spirituality. Serious misgivings begin to compel me into an estranged entanglement. This incongruity tarnishes the summary of reflections and memories I have of Jim, meaningful reminders I want to capture and frame like a work of fine art in the homage of a cherished posterity.

Affection between Jim and his parents, as well as Jim and his siblings engenders universally in the testimonial microcosm of family relations. Its rawness is unequivocally compelling as it recognizes a depth of vital and evolving emotion. This respect for lineage as an inherent contributor toward the perception of a loved one’s passing, although personal and distinctive, can announce an exclusiveness. Suffice it to say, is this motif of prescribed codes more peremptory than the love between Jim and me? Does the family’s orthodox position usurp more power than our unorthodox one? These questions ignite an opportunity to challenge the social order: a revision of consciousness, a prompting of another testimony, a critique of conforming paradigms that have normalized the temperament of our attitudes, behaviors, and experiences. The familial forces of the status quo can unintentionally sever the integrity that champions the unconditional nurturing bonds between two men can grant.

Mortality Resisting Spirituality

As a believer in the Lord’s mercy and an advocator of Jim, my reservations amplify as this practice of sundering ashes surge as a measure of triviality. This thorny notion clamps me like a muscular spasm. It gnaws at me with the burden of extracting from it the significance of spiritual responsibility. A fulcrum of doubt in divine conviction is raised as in a drawbridge disconnecting Jim’s corporeal life from his eternal one. This view, from my mindset, puts faithlessness in motion like beach waves swelling and shattering. Without reservation, I want his ashes to remain with me, and then inter with me in my family plot when I pass-a commitment compelling a solemn rite. In the [sic] of Jim’s last will and testament, “I appoint Anthony as my executor. I hereby direct that my body be cremated, and my ashes be scattered in a place and time to be solely determined in my Executor’s discretion;” there is no catalyst for ambiguity.

Although scattering ashes is generally symbolic of secular freedom, the choice contradicts, “I am the way, the truth, the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6). A casting ceremony separating and dispersing Jim’s cremated ashes goads limitations in the quest for an afterlife. This capricious act disburses Jim as if the energy of his being were undefined matter eroding in the vacillating movement of the wind, or baking soda particles spread on a rug. It translates as an intrusion, belying the climax of Jim’s glorified destiny—the ineffable mystery of faith. Final disposition as a reverent abstraction becomes obscured. The failure to interpret an end-of-life concept mystically as majestic finality materializes. Notions of disbelief collect within the confines of an absent scope for “plentiful redemption” (Psalm 130 (129):7.

With this dissemination position, although grounded in felicity, there is a subscription to an alien conception succumbing to a limited understanding of the relationship between faith and reason. For me, it waives as a whimsical act negating, “Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed” (John 20: 19-31), in the beauty of spiritual supremacy. This belief applauds the skeptic who does not view the foundation of infinite perfection through hope. By doing so, Jim resides in the gloom of a sacred void. The decision rebuffs the transformation of his body into soul. Then, migration to “eternal inheritance” (Hebrews 9:11-15) ceases, relegating to something not metaphysical but mundane.

Equally important, parting with the totality of Jim’s ashes subverts the stature of our life together. It unfolds as a deception. The complacent conjunction that has chartered our relationship throughout the years in the landscape of joys and sorrows processes in a wail of detachment: The genial glances over coffee, the harmony of an embrace, the magic of laughter, the contentment of our conversations, and the spiritedness of walking shoulder to shoulder all dismiss their intrinsic loyalty and shift to the distance of treachery. Those profound moments together become overtaken and love’s reciprocation mangles in a disregard effacing the strength of our divine bond. Without the insight from Saint Paul’s, “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ?” (1 Corinthians 6:13c), Jim thrusts into the consequences of decay. This dissolution scoffs at every furrow of our connection while neglecting the anima of Jim’s human and intangible identity.

The Sight of Death

The mortician asked me if I wanted to view Jim’s body prior to cremation. Although the anticipation of the sight of Jim in death polarized me in a shivering reality that seemed illusory, I agreed. None of Jim’s family or friends attended the viewing. Just my sister and me. We stood motionless by the alternative casket where Jim lay, a presence concaved in an oblique sallowness. His collapsed being coffined the declaration of the once abundant gift of closeness between us. Now, I am left in a turbulent solitude strewn with broken flashbacks. He lay there in a conviction confessing little doubt—no longer imprisoned by the heavy hand of unyielding suffering. The reward of a long-awaited blessing now softens him. He was bound from the neck to the waist in an eggshell-colored inflexible canvas sheet that could pass as a straitjacket. I spared myself further anguish by not asking the mortician the reason for this peculiar attire. Brittle limbs slumped within an elongated prostration. His legs and feet were concealed under the fiberboard covering of this substitute casket. A face, once handsomely commanding, now a haunting portrait, received me. I scrutinized him as if I were waiting for a sign, a response, a movement, a murmur, a definitive expression, or something from the past when Jim cultivated hours of living without affliction. Yet, nothing imposed but a presence sedated in a steely stalemate.

An unusually vacant silence suffused itself as I took a seat at the opposite end of this spartan visitation room. It felt austerely indifferent with no furniture, flowers, or visitors there to pay respects. Only a stab of stillness chafing my sister and me. I sat in the room’s imperturbable remoteness, pensively glancing at Jim, attenuated in carnal display, reconciling myself to a choking of unmasked wailings. My sister kissed Jim’s head and made an affectionate gesture to his chest. A spirit, concentrated in the realization of a flagrant truth that can engulf one’s senses, took control of the room. It persuaded Jim to simultaneously deny existence and indulge inevitability. The preservative erased the greying shadows on his forehead and the hollow indentations of his cheekbones. Although, of course, there was still a skeletal, shrunken quality about him. An outline of Jim’s clasping hands protruded through the covering. His skull maintained some patches of hair, along with a full moustache, both thinly coarse and grizzled stiffly in a brown and white dissolved hue.

My sobs rekindled as I stepped to his side. I crossed myself to not give into the reprise of sorrow inscribing my chest with a vibrating ache. I kissed his lips, lips whispering in cadaverous obstinance. The state of repose nursed the deception of resting. It altered my previous understanding of the life of the dying with cancer’s megalomania and its frightful end-stage manifestation in hospice, where Jim’s body rattled in toil, awaiting release. In those final moments there, he thrashed and waned, convulsing in violent and frightening wheezing as the breath left him. The tumult of delayed fading and then triumphant expiration, one hard to grasp process acquiescing to the other.

Catholic Paragon of Resurrection

Spurred by the Genesis reference, “By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return” (3:19), I needed clarity. I wanted an answer. I prayed for deliverance in an unfettered pursuit of divine truth through Jim’s ashes. As a student who was educated in Catholic schools, I was intrigued by the teachings and rites presented in The Book of Common Prayer. I learned to revere goodness and scorn evil. I listened in amazement to stories about the integration of mortal reality into divine reality. Christian themes conveyed in the New Testament about the Lord, his resurrection, and if one believes, one will have eternal life, all seemed plausible to me. Although, as an adult, my notions about holiness, sin, and human weakness emerged with considerable fragments of rejection. The batch of recurring trials and crosses we must regularly bear bolt me in a reverberating quandary. However, I have never lost my faith in God, or Christ. In this consequence for finality, I was clamoring for the saturation of comfort. Although my heart, in its omniscience of jaded anguish, obstructed any prospect for consolation. Through the depths of my darkness, I was subliminally pleading for the light of a fix to compensate me for the heavy and prolonged storms Jim’s death slammed into me.

So, I went to my church. Father John engages the Sunday liturgy with a revelatory voice and articulation absorbed in an erudite confidence. During his Sunday Masses, Father John always delivers his duty elucidating the Scripture through a Saint Thomas Aquinas affirmation demonstrating divine faith. His manner, a cachet of polished authenticity, radiates cerebral enticement. Father John speaks of the need to actualize the mysteries of faith culminating in the body, blood, and soul of the Eucharist-the imperative nurturing agent in Catholic lives. He incarnates the complexity of such an undertaking with courage, significance, and a tenacity professed in the acknowledgement of a higher power. Father’s tall frame, structured in a pronounced beveled figure, dwarfs a rigidity in gait as he genuflects before the tabernacle in a concentrated kneeling of structured devotion. The hovering nebula of frankincense devoutly embeds like a tapestry weaving the divine conundrum distinguishing the colors of his liturgical vestments. While he raises the Lectionary Book of the Gospel and proceeds to the pulpit, he ruminates in the secular realm of human experience. Father John assumes the ownership of sin, not in the second person plural, but in the personal context of the subject pronouns “I” and “we.” These objective word forms are always on his lips. His leadership and the parish coexist in the reception of universal sharing. Father John is devoid of any pious ego during his homilies. Confessing to his own fallibility, and we, in ours, the congregation welcomes Father John as an emissary to God.

Following one Sunday Mass a few weeks after Jim’s death, I approached Father John with the intention of asking him if he would bless Jim’s ashes. I stood before Father’s demeanor, an impassioned presence summoning ideological theism. I wanted to know his personal thoughts, which commutatively, are synonymous with the sentiments of the Catholic Church about: interment through cremation, the appropriate dwelling place of ashes, and if dispersion to family members is religiously ethical. When I told Father John I keep my partner’s ashes at my home in an urn on a bureau with rosary beads draped on its surface, his face roiled with implacable disdain. “The body is a temple of reverence to Christ, and the Catholic Church enforces strict rules about cremation,” he informed in an attentive tone.

Then, he gestured for us to move out of the vestibule area where the ingratiating banter of some parishioners magnified in volume as they awaited in grace for the pastor’s greeting. We took a few steps to the interior of the church just behind the last row of pews. A glass encased sculpture of the ravaged Jesus dangling inert reposed before us at a pedestal of flashing candles. With the suggestion of correctional admonition, he added, “According to the Vatican, separating ashes is a form of desecration. Ashes should not remain in someone’s home for any extended period; since a home is not a sacred place but should be interned in a cemetery or in a consecrated place.” When I added that I made certain the hospice chaplain gave Jim the last rites (fishing for a bit of atonement), Father John’s face took on a contented look. The violet, amber, and emerald colors wove rapidly from the stained-glass windows diagonally above us during this exchange. The stubborn sun advanced in a pouring of rolling crochet patterns fusing the array of 14 stations of the cross on the wall. The depiction shingled Father John’s face in a gauzy oscillation as it juxtaposed Jesus’ fall a second time on his way to Calvary. The pastor then excused himself from the parishioners’ pleasantries and proceeded to the sanctuary where he passed in Father John’s line of vision. Father took this as a signal to tie up the loose ends necessary after the final twelve o’clock Sunday Mass. “Let me know what you will do,” he said as he followed the pastor to the altar.

Father John left me with a smile and a handshake. His words, blazing in the assertion of Nicene Creed, the foundation to spiritual everlasting, evaded me. I found this too sacrosanct to challenge. And the conversation fell short of my expectations. In the requisite of unwavering canon, my possession of Jim’s cremated ashes–immortal wreckage– unquestionably valorizes the dereliction of his soul. I weaken in the feeling that Father John spurned my sorrow for the sake of resolute dogma. And these sacred teachings accompanied punitive subtleties. I was not posing philosophical rhetoric on Christian faith. I wanted a priest’s reassurance that Jim would be sanctified, rewarded compensation for his monstrous suffering. Consolation from the Lord is promised and can be summoned. It is not vague. I felt foolish, reduced to the air of a helpless child. I was too timid, too tongue-tied to ask, “So you cannot bless my Jim’s ashes?” as he departed. I was seeking a bending of theological rules, an egalitarian reassessment of epistemology to defend my personal petition of eternal enlightenment for Jim.

I became consumed in a panorama of troubling multitudes: life, death, divinity, sin, evil, virtue, relationships, faith, disbelief, remorse—all irresolvable in my subjective thinking. These ideas continue to torment me with their distinguishable meanings. I needed Father John to say that if keeping the ashes with me until I pass makes me feel closer to Jim and God, and compensates me in my grieving, then do so. I desired an epiphany to obliterate my somber struggle. I hoped Father John would endorse my resolution, my version of ecclesiastical tenet. I wanted Father John to tell me God did not abandon Jim, despite my choice. All the same, he covertly dismissed my interpretation. I left the church that day yielding to the ignominy of restless self-reproach as my body moved in an unusual reluctance. My shame weighed greatly like a formidable omen. I could not be rescued from the limbo of damnation. The afternoon sun was beginning to drive a fluid aura abruptly chronic between brilliance and shadows. A richness of isolation descended. By the time I reached my house, a silent smoldering of gray unfolded.

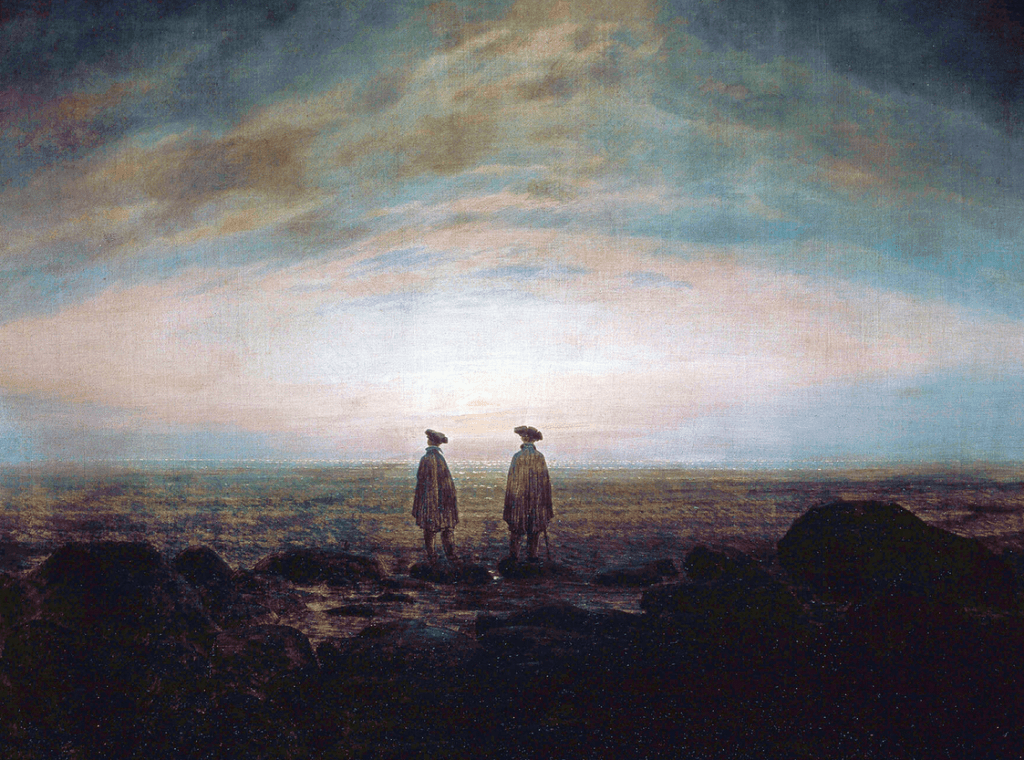

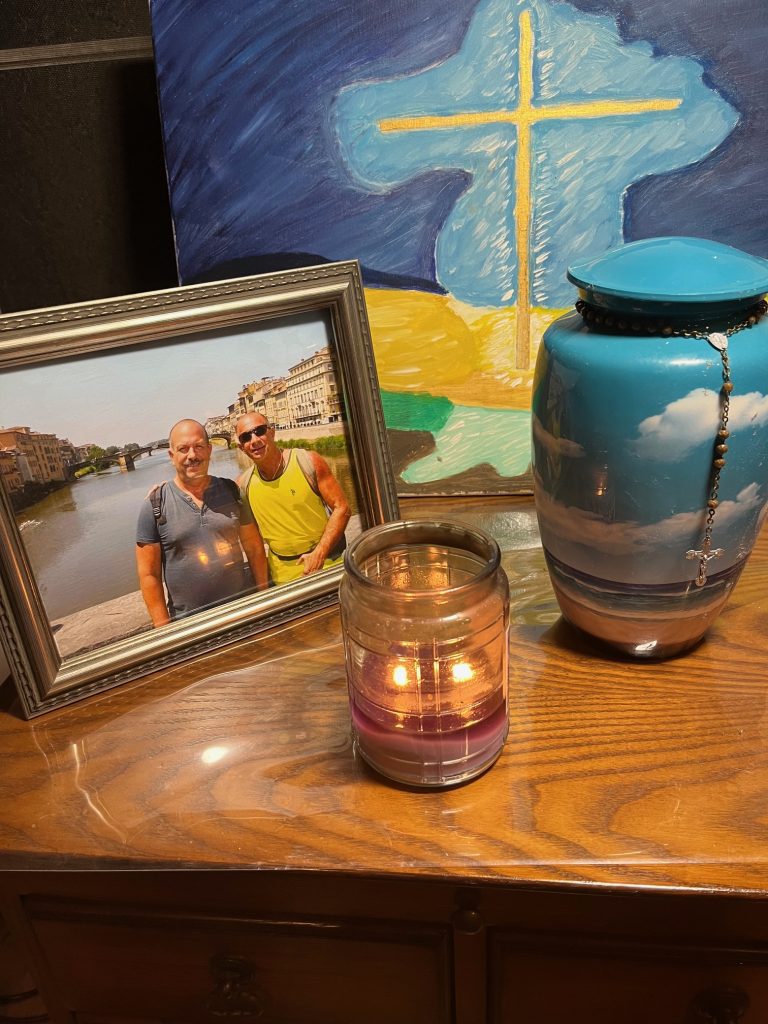

A Symbol of Perpetuity

Integral to my breach of Vatican edict and to the latitude of vindication permitting Jim participation in salvation, the urn rests on my dresser today. I try not to think of my choice as blasphemously self-serving. Rather, I perceive it as God’s reconciliation with me triumphing in his merciful commitment to Jim for eternal life. This ceramic vessel captures seascape designs highlighting a beach pivotal between an azure sky above and raw umber sand below. The imagery invites Jim’s affinity for nature’s quintessence with the summer solstice coaxing a vigorous fervor for life. I frequently light candles at its foot and rewrap rosary beads when they slack from its narrow neck.

To the left of the urn is a picture of Jim and me taken at Bridge Ponte Vecchio. There is a permanent place in my mind’s mirror where the image of us together abounds in the same radiance the day the picture was taken. We posed in the vision of prolific joy as I caressed Jim’s shoulder. It was a trip that deafened in the harmony of freedom. A romantic inclination presumes we stood in the same place before the bridge where Dante met Beatrice, his muse and lover. The “Bridge of Gold,” the transcendence of profound love. Jim looks so youthful, a sublime vision contradicting time, possessed by a husky vitality festooned by the Italian summer sun. Jim and I on the Old Bridge everlasting. No messengers of death. No corridors detouring into the chaos of disease. Only the purity of an eternal still-life, immutable, no ceasing.

Credits

Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur Bochner. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung Vol. 36, No. 4 (138), Conventions and Institutions from a Historical Perspective / Konventionen und Institutionen in historischer Perspektive (2011), pp. 273-290. Published By: GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences.

Featured image by Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, 1819-1820, Wikipedia

Caspar David Friedrich, Evening Landscape with Two Men, 1837, Wikimedia

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men by the Sea, 1817, Wikipedia

Photo by author

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

I am a retired high school English teacher from New Jersey. I recently received an online Masters degree in English Language and Literature from SNHU. I am grateful to Dr. Marlen Harrison, who mentored me and inspired me to write from an autoethnographic perspective.