One Man’s Perspective on Grieving and Death

Author’s Memo

Narrations that evoke motifs of truth and vulnerability authenticate the essence of autoethnography. A writer who engages in autoethnography personifies philosophical and psychological struggles within his internal and external reality. Robin Cooper and Bruce Lilyea elaborate on the autoethnographic genre in an article entitled, “I’m Interested in Autoethnography, But How Do I Do It?” Cooper and Lilyea define autoethnography as a qualitative phenomenon that ascertains explanations about the human condition. The authors allude to a myriad of researchers who render the value of empiricism as the archetype for exploration. For example, Butler-Kisber (2010) affirms, “Individually or collaboratively they use narrative dialogue, self-study/ autobiographical and memory work to construct stories of their own experiences” (65).

Another researcher the authors allude to is Chang (2008), who extends the “auto’ notion in autoethnography by stating, “Stemming from the field of anthropology, autoethnography shares the storytelling feature with other genres of self-narrative but transfers mere translation of self to engage in cultural analysis and interpretation” (43). Therefore, autoethnography can integrate individual perception in the emotional response to conflicts with the sensibility of cultural universalities that moralize upon the human experience.

‘One Man’s Perspective on Grieving and Death 1 is a narrative representation of death as a universal humanistic theme.

“One Man’s Perspective on Grieving and Death”: Part 1 is a narrative representation of death as a universal humanistic theme. The hospice setting is allegorical in nature since it is the embodiment of emotional and intellectual insights into loss as an existential and spiritual concept. My non-fiction anecdote portrays impressions and observations of a reality between myself and my partner, Jim, who was dying of cancer this past year. We were left to each other to endure an emptiness and anguish that descended upon us while awaiting Jim’s imminent death. A myriad of emotions, thoughts, negations and apprehensions materialized during our crisis. Our interactions always revolved around the unfathomable idea of death as it penetrated our psyches daily.

The notion of a death experience, and my interpretive conceptions of it, evokes the compelling essence of autoethnography. In this sense, I wanted my written inquiry to enhance aesthetically in the realm of literary discourse. Although frighteningly painful, I needed to confront and convey traumatic insights from my tragedy as a cultural conceptualization of death, a social phenomenon that warrants conversation and study. Specifically, I wished to communicate the idea that the death of a gay partner is just as emotionally monumental in the landscape of grieving a lost relationship as is the death of a heterosexual spouse. It exemplifies the same degree of affection, devotion, and yearning for intimacy. When I spoke of Jim’s death with a colleague of mine, her reaction was, “Think of the grief I went through. We were married for forty years.

‘The affirmation of mourning the loss of a loved one and the loved one’s process of dying…

You can’t get any worse than that.” The subtext of her self-involved comment intimates my relegation to a lower semblance of feeling; since, my relationship with Jim does not significantly subscribe to the traditional realm of emoting that a heterosexual couple elicits. This biased line of thinking presupposes that relationships between two men or two women are non-entities in this social/ cultural hierarchy of perceiving grief. This convoluted attitude toward same-sex relationships defy the limitless sphere of emotions all humanity experiences and that are universal in theme. We all confront the process of dying as an existential trial. It transcends all social institutions.

From a psychological perspective, the setting and insights in “One Man’s Perspective on Grieving and Death”: Part 1 construct a measure of profound loss as two people part by death. Fear, grief, pain, and mourning equate as a paradox in the culmination that love brings between two people. The affirmation of mourning the loss of a loved one and the loved one’s process of dying are explored as a qualitative inquiry.

Work Cited

Cooper, R., & Lilyea, B. V. (2022). I’m Interested in Autoethnography, but How Do I Do It?” The Qualitative Report, 27(1), 197-208. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5288

One Man’s Perspective on Grieving and Death: Part 1

“so I have been allotted

months of futility,

And nights of misery have

been assigned to me.

When I lie down I think,

‘How long before I get up’ (JOB 6:29)

An Effigy of Grieving

A bronze statue stationed in the lobby entrance at Calvary Hospital in Bronx, New York evokes an image of unfathomable suffering. This representation of anguish presents caretakers enveloping the fading affirmation of life on a figure’s disturbed face and ravaged body within the gift of altruism. The certitude of grieving and death triumphs as a whole dimension. The brass inscription just below the figure clearly states, “Whatsoever you do to the least of my brothers, that you do unto me.” It is a depiction featuring the vulnerability of the disenfranchised, those deepest in despair. Intrinsically, it pledges the mission statement of Calvary, a hospice facility committed to relieving the physical and emotional torment concomitant with the process of dying. It is there that Jim, like the forsaken Christ fated to hauling his cross to Golgotha, was exiled for twenty-three days.

This formidable reality assumed an unconditional acquiescence to the nadir of his terminal illness. The concept of hospice personifies the prophet Isaiah’s words, “like a lamb led to the slaughter or a sheep before the shearers.” In Jim’s case, however, it was an admittance with the mindset of disengaging innocence while embedding the dread of heavy blame. After two years of experiencing punishment like someone nefarious from a cursed world, Jim reluctantly yielded to an onslaught of existential multitudes. There were fleeting times when his mind quarreled in a sort of implosion with marked bouts of covert rebellion as the inevitability of death encroached. I could see it in his furrowed brow and in the severity of his eyes.

‘This formidable reality assumed an unconditional acquiescence to the nadir of his terminal illness.

Nonetheless, there was always fated compliance to physical and psychic suffering, inexorable self-reproach, struggle, denial, anger, and a testament to the empirical truths and paradoxes that force a showdown. His was a body and mind fully embroiled in the anticipation of his own insignificance through death. This sojourn became a metaphor for the self-evaluation of his transgressions.

Consequently, the irrevocable hopelessness of his cancer was always an imminent peril despite the launching of the potential for hope with targeted therapies and clinical trials. These became a veneer of false positives laden with the guile of optimism.Doctors prescribed incessant Pet scans, MRIs, and CT imaging throughout the year 2022, and all revealed disintegrative changes in tissues and organs. There were a few times when the results of a test would report a suppression in the growth of the tumors (just a false alarm), specifically, the villainous one that was lodged in his pancreas, the nucleus in the procession of Jim’s suffering. This disclosed and amplified during the times we would sit together, and I would inadvertently glance at his wincing face as he brushed against the left side of his abdomen with the palm of his hand to fight the agony.

‘Nonetheless, there was always fated compliance to physical and psychic suffering, inexorable self-reproach, struggle, denial, anger, and a testament to the empirical truths and paradoxes that force a showdown.

Then, there were times when he would recline with his phone in hand and listen to his music, retort to his politically conservative Facebook friends, and engage in casual conversation with me while remaining undaunted by the power of his plight. Yet, a remorseful silence would resound as he sat there in thoughtful collection about his cancer. In the last few months of Jim’s crusade, tests concluded aberrations in visceral manifestations that warranted pathological doubts and negations. Oncologists finally declared that the rigidly mandated algorithm of chemotherapy and radiation treatments hereceived every three weeks, as well as the insidious disorders emerging from the development of new carcinomas warranting extensive hospitalizations, were all errored exercises in futility. Treatment proved to be just a contrived fleeting from the proliferation of cells, a mocking of hope, bereft of any peace of mind.

The systemic therapies that were prescribed by a team of research oncologists could no longer rescue Jim from the waxing of tumors, whether they be internal or external. These treatments also proved inept at thwarting the fatal progression of residual infections emanating everywhere from the liver, the pancreas, the intestines, and the spine. So, they could do nothing to combat this capricious agony, this unalterable fear that ceased any cherishing of well-being.

The Solitude of Caretaking

During Jim’s twenty-three days at Calvary (administrative statistics measure the average patient stay to be 26 days prior to death), I unquestionably immersed myself in a regimen of caretaking for Jim: -my significant other, my partner, my best friend, my soulmate, my brother, my child – all the permutated, possessive interpretations of the traditional concept of coupling we commit to in our chase after illusive joy. These roles befell me with unrestricted devotion and deed as my heart would break and contract chronic pain watching illness incarcerate him during those steadfast hours of the day and night. This tumult afflicted both of us with a remote aloneness. Reciprocal emotional ties had become part of the same void. Our need for each other’s closeness would dissipate in the thick of this cancer’s enduring fury. It created an anchor that attached us to the conjunction of adversity.

Daily tears of sorrow descended as Jim’s agonizing hell also became my purgatory. I bore witness to his absorption into an incoherent and empty world that was irreversible. He emerged like a prisoner on death row of undetermined duration, and all my solace could not shackle the barriers to his intractable reality. No snorts of enraged blasphemy or amicable supplication could rival Jim’s nemesis. It was instinctive to the perplexities of temporal loss under the enigmatic heavens.

The Physical Construct for the Dying

The wards at Calvary Hospital inhabit areas cloistered in sparse antiquity. The patients’ rooms are situated in a theater-in-the-round configuration surrounding the nurses’ station, an enclosed area that aligns the floor’s perimeter. Walls coil in a presentation of pastoral scenes depicting Jesus as the safeguarding shepherd. The space encompasses computer monitors, storage units for controlled substances, carts with patient data stored and featured on laptop screens, and alcoves for patient linens, gowns, and adult diapers. In the verisimilitude of a 1970s college dormitory, rooms have arrangements in groups of two with an adjoining bathroom that both patients share. In most cases, however, the nurses and patient care technicians, who regularly dispose of urine, feces, and infectious fluids utilize restrooms . The patients, all bedridden, are left tethered to the responsible inclinations of the custodial staff, who govern autonomy over their omnipotent distress.

Each room has a double hung hinged window that bolts sealed to the unrestraint of fresh air, leaving the rooms in stifled confinement. An assault of odors, stagnated in humidity, from food trays, human waste, and the medicinal toxins released through the tainted pores of patients can stupefy one’s olfactory sense. The putrefaction of internal organs and the yellowing of flesh remain in the embolism of infirmity. Depending upon which side of the building the patient lodges, the vista overlooks either an unoccupied courtyard that accommodates empty chairs and tables, or a parking lot jammed with cars. Cohabiting in their own respective marriages to dereliction and melancholy, with a projected vision never distancing beyond their hospital gowns, patients evade, with veiled eyes, the natural light coming from the window.

‘They will never enjoy a winter, spring, summer, or autumnal splendor. The only perception of light is the fading rays that reach and tremble on their stoic faces.

They will never enjoy a winter, spring, summer, or autumnal splendor. The only perception of light is the fading rays that reach and tremble on their stoic faces. A wooden crucifix is secure on a wall adjacent to the window. I would frequently clutch this symbol as I addressed a silent prayer in the hopes of an end to Jim’s poverty of grace. And of course, there are the death beds. For months and years, these beds become inhabited by countless souls grappling with agony. These beds are the foundation to the input of patients’ external reality, the foci of their obliterated solitude. Sheets overlay their cumbersome and prolonged suffering, battle-scarred in isolation, as they wait for reprieve.

At designated times, the door opens, and the nurse cordially enters in perfunctory manner and greeting. Patients awaken to the monitoring of vitals and the administering of medications for pain, or to treat ancillary symptoms related to their disease. The technicans who deliver trays of food on overbed tables opened doors less frequently. Some of the afflicted are capable of relishing, while others leave the food to chill in unsavory aversion. Jim would try to eat a few bites, push away the tray, and withdraw to the pillows propped behind his back, and at his side, as he would glower with nausea. In the more reluctant moments, aides come in to clean the soiled beds the residents can lie in, sometimes, for hours at a time, unless a family member is there to call and expedite the washing process sooner.

‘And of course, there are the death beds. For months and years, these beds become inhabited by countless souls grappling with agony.

The medication cart is left outside the patient’s door as the nurse documents what treatments are to be rendered based on a timetable of doctors’ orders. Patients are punctured with needles and ingest pills. As their extremities tense, a vague tremor is released just as the opiates imbue through ruptured veins and soon, they pervade a body that yearns to exit from this world in unconditional submission. Some have visitors who come to comfort them with soft intonations and touches, while others battle through their suffering in an inert aloneness. Either way, all are rebuffed as they embrace the advancing claws of inevitable death. In the corner of each room stands an IV pole device that can become readily available for self-induced pain killer infusion pumps, specifically the traditionally directed morphine.

Jim would briefly be tethered to one, but the standardized dosage did not dull his obdurate pain. So, the alternative was to infuse Jim with higher concentrations of methadone and hydromorphone through a port-a-catheter located under the skin of his right chest every eight hours and six hours, respectively, to lag the habitual pain. Jim would lash out in frustrated exasperation, as he would argue with the nurses and myself saying, “No, ya got it all wrong; I take the morphine every six hours.” The confusion on his face, grimacing in the heated crimson of a chided child, would succumb to permanent desperation, as if we were conspiring to deflate his competence. Any explanations to the contrary expressed with affection and politeness could not persuade him otherwise.

The Permanence of Desperation

While Jim’s eyes occluded in a glaze, I would stare with distress at a body and face tortured by brutality and listen to the murmur of his groans, raucous in the degradation of his existence. Sometimes, he would raise a trembling hand and his fingers would grasp at the air just above his eyes as if he were swatting an insect. Then, something odd would prompt provocation; he would return my fixed gaze with the inquisition for some truth. I wanted to cry out, “What will I do without you?” However, my face averted in the embarrassment of such a mawkish plea. He sensed a strangeness in me and asked me how I felt; the question would be a foreshadowing of the crippling hollowness I would soon assume and reside in for months to come.

I would occupy a body in somnambulism as a dragging sense of grief would demonically possess me. The suppressed feeling would then betray itself and compel me to surrender and whisper my histrionic request, “What will I do without you?” Jim would hear these words in a commotion of muttering through my croaking and desperate sobbing. Jim would then retreat to the howl of his own distress, shrinking into the refuge of remoteness.

‘I would occupy a body in somnambulism as a dragging sense of grief would demonically possess me.

Dr. Zaretsky, the Hospice unit physician with an unhurried walk and an approachable demeanor, warned of the onset of permanent delirium that Jim would soon experience. He suggested that this state of mind is part of the typical trajectory patients experience during the final stages of terminal cancer. In a thick Russian monotone, he asked me, “Does Jeem know you? Sometimes, zay become forgetful and do not communicate vit famly. Zis is not uncommon, and usually zay pass in za veek.” This stage of agony persisted a few days before Jim’s passing. There were moments when Jim would awaken from his opiate state with a tranquility that comes from escapism as his face drew a melancholy smile. Jim spoke of the simulated travels experienced while sleeping, including trips to Europe, and long drives he took to European cities in his car, and the people he once knew.

He recounted these illusory moments with a sense of felicity; there were no traces of being engulfed. Soon, though, a quarrelsome and alarming state would unfold, and the heavy and amplified suffering would rage again. Jim’s cognitive decline was sudden and severe as he began to verbalize in a boisterous menace. Violent tremors began to invade. A frenetic horror conquered his face. The incoherent fragments and slurring of words that bellowed in desperation seized and frightened me: “Wherz door,” belligerent “Nos,” screams of “Help,” and what sounded like talk of seeing a narrow tunnel and snow, accompanied rousing movements in his legs as he tried to shift his trembling body and flee from the bed. What visions and voices manifested during this battering transformation? Jesus, guardian angels, demons, an abyss. I would try to quell his violent convulsions with a soft concession of comforting hands.

‘He recounted these illusory moments with a sense of felicity; there were no traces of being engulfed.

However, as the quavering grew more erratic, I called for the nurse, who would instill additional pain killers, and within minutes, Jim’s state of arresting alarm transported into a reticent drowsiness. At the window, the February sky begins to cloud over in dark and portentous billows as I flipped off the switch to the sharpened fluorescent light above us. While Jim departed into the agreement of oblivion, I sat at his side in the tumult of a sullen silence.

One Man’s Perspective on Grieving and Death: Part Two

Companionship in Imminent Death

Daily visits to Room 418 at Calvary cultivated an unwavering synthesis of love and grief. Visions of Jim and the images of transfiguration through his meaningless fate inundated my psyche and persisted in a permanent turmoil. I sat at Jim’s bedside daily and into the evening hours, witnessing him drifting in and out of a lethargic consciousness. We would watch Turner Classic Films, to which he was mostly inattentive. Yet, sometimes, an awareness of his surroundings would emerge, and he would react to a scene or a line of dialogue with a grin or a wry comment. Even so, a ceaseless sorrow would always surface. I would reach for and embrace his hands, flawed and pulsating in dispirited fragility, massage his shoulders and back, which magnified meagerly in mass– a build that I now pronounced with protruding bones.

I would sponge bathe him, guide him to the bathroom when he was able to walk with the assistance of a cane in his left hand and his right hand on my shoulder. In this routine, I also maneuvered a thin hollow tube that extended from an incision made in his stomach to a biliary collection pouch, which retrieved and stored contaminated bile fluids from his liver. They performed this methodical juggling with vigilant effort to prevent the tube from detaching and to circumvent Jim from collapsing. When he was too weakened and unsteady to use the facility, his body would release to the mortification of bowel incontinence, which then warranted attention to the soiled bed.

‘Daily visits to Room 418 at Calvary cultivated an unwavering synthesis of love and grief.

So, I would wipe away the excrement that bundled from his collapsed torso in a thick stream that ran down to his inner thighs and soothe the ensuing chafing with aloe vera creams and ointments. I would make sure not to saturate the medicated hydrocolloid dressings taped to Jim’s backside with bath water. This would impair the healing of the skin ulcerations that resulted from the pressure of lying in bed too long. I would try to comfort the alarm painted on his face and the murmuring that vibrated from groans of longing with gentle whispers of tenderness and stroke his head when the hallucinations unfolded as they prompted violent movements signaling from his limbs. I would impede the rattling noises persisting from his throat like an unstoppable hiccough with a kiss on his chapped lips, parched with sores.

And just before the dreaded end to visiting hours, I would prepare his toothbrush with paste and fill cups with water and mouthwash for rinsing, — all in the effort of consoling the arresting solitude of his affliction with some unremarkable semblance of the ordinary.

‘A nurturing persona defined my identity for the last six months of his life.

I thought the caretaking would never cease. In fact, I, selfishly, welcomed it even if it meant seeing Jim one more time with no intention of accepting death. A nurturing persona defined my identity for the last six months of his life. It grew even more paramount in the last few weeks as he lay ensconced in Hospice execution. I wanted to ensure protection from the curse he had been resigned to, and the even more abomination that would soon arrive and would not abandon him in this relentless condition. I considered the possibility that perhaps this demise would loiter. Jim would often say, “How much longer can I go on this way?” not in the whining of self-pity, but in the philosophical reasoning for God’s heavy hand.

In the absence of an answer, Jim’s head would then droop in self-defeat. This abeyance can afflict patients at Calvary, who for months and in some cases a few years, lay implacably tethered to their austere world, mouth agape, sunken and bulging eyes dotting hollow blanched cheeks, and palsied limbs dangling. This is, appallingly, not uncommon. They all just wait for a glorious resurrection that would renounce their expiation.

Loss and Self-Reproach

The narcotics for pain assisted Jim and all the other deformed bodies to willingly consent to their own crucifixion. They have no choice, but to endure daily, in the hope that mercy would arrive. For Jim, the tyranny finally ended at 1:15p.m. on a grey Tuesday afternoon, the last day of February, with slushy wet snow cascading on the dense landscape of city streets. God’s mercy materialized for Jim, while God’s wrath would promulgate for me the law of faith decreeing the endurance of a perpetual ache that comes from loss. If the severity did bolster, I still would have faithfully visited every day to sustain the nurturing.

Anything less, would avail as a haunting guilt beckoning me with contrition, a connotation of betrayal to the reiteration of “I love yous.” Yet, the contradiction was, that every night when I left him, I prayed for the Lord to take him. He was no longer the buoyant voyager with the affinity for wanderlust. He became bound and tied to this egregious malady, tethered to immobility; this embittered him to permanent desperation.

‘His absence would plague me with emptiness, alienation, and the internment of an uninterrupted misery.

When it was over, and in those embryonic hours of the oppression that comes with bereavement, I was convinced that I would never be able to relinquish the sorrow because renouncement would be synonymous with love’s derision. His absence would plague me with emptiness, alienation, and the internment of an uninterrupted misery. I felt the blameworthiness that survivors feel. There were moments when I wished I had left with him or left before him. Spontaneously, and with a yearning for nearness, a memory of Jim would set in, and rouse my sensibility through images of an endearing facial expression, a conversation, an empty chair, a song, or one sock serendipitously found. No, he can’t be dead. We are only in our 60s.

The stray cats at the city subway are waiting for us to feed them. We always go to Starbucks on Saturday on the way to the gym, and we must plan that trip to Europe before there is another lockdown. We only know life in its present tense of absolutes, not in this nebulous face of dissolution. This would induce bellowing cries that would originate deep in my gut, and proceed to galvanic disengagement, a bleeding combustion. Tears would trickle and grate the skin beneath my eyes in raw lacerations.

‘The dozy sense of euphoria withdrew. Instead, a realization surfaced. With a fixed gaze of contentment, he said, “I could have never gone through all of this without you; you’re a gem.”

It was in that one inexplicable moment that I will always recall when his imperceptions translated to an astute realization. Jim’s tribulations from cancer suddenly paused as if healing was conceivable and clarity took form. His eyes no longer abstracted with the distance of apoplectic vagueness that stems from the infused pain killer cocktails of methadone, hydromorphone, and morphine. The dozy sense of euphoria withdrew. Instead, a realization surfaced. With a fixed gaze of contentment, he said, “I could have never gone through all of this without you; you’re a gem.

The beam on his face that followed both elated and devastated me. I could never emotionally comprehend an acceptance of his disintegration, and this would terminally change my perceptions about the meaning of life, my former life with him, my present life without him, and the scrambles of existence. His gaze, one of profound reverence, would leave me spellbound as it propelled a noble loyalty to him that I would never consign to oblivion.

‘Despite the hopelessness and suffering demonstrated before my eyes, I deluded myself for a miracle.

For some absurd reason I concluded as truth, my dubious nature would intervene, and counteract all the felicity between us. I felt I didn’t do enough; somehow, I could have helped him thwart all of this. In my compunction, I would attract anger and bitterness from his loss. Jim’s appraisal was no compensation for some failure I felt arrayed in my conscience, and my affection was no compensation for his vortex of fear. Why did I feel this responsibility for his cancer? Perhaps, I could have sensed the urgency to bring him to doctors sooner. There was no rational explanation, but I still could not mitigate the intensity of this regret as I watched the nurses infuse quantum of painkillers through his port day in and day out. Despite the hopelessness and suffering demonstrated before my eyes, I deluded myself for a miracle.

I wanted Divine Intervention to sabotage the truth and the knowledge of well-being for Jim. I called for the priest to anoint Jim with the last rites. This sacrament would atone for the burden of suffering Jim was relegated to for so long and I also wanted reassurance that Jim’s cross rewarded him with eternal life through the death of Jesus Christ. The priest, exuding a composure complemented by the simplicity of his black attire, introduced himself and stood over Jim’s convulsive breathing. While blessing the palms of Jim’s hands and forehead with holy oil, the priest recited words from the Commendation of the Dying, “Eternal rest grant unto Jim, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him. May Jim rest in peace. Amen.” The priest and I then recited the Lord’s Prayer in simultaneous reflection to the refrain of Jim’s distress.

Images of Suffering and Redemption

In the afternoon of his passing, alarming images would sustain. I will never be able to erase the ominous transformation that took place in an unrecognizable face, a face disjointed from freedom, a face that struggled with breaths goaded by violent convulsions. The strenuous process of breathing was evocative of the hellish sounds that are made during the interaction of power press factory machinery, reverberating in gasping remnants. Jim’s strained process of inhalation and exhalation was unsuccessfully mollified by a plastic apparatus shield that canvassed his nose and mouth in efforts to assist respiration. Yet, he was suffocating, and I was watching in a terror-stricken helplessness. It was at this moment that I witnessed Jim in the juxtaposition of extremes spanning two worlds: a blessed realm summoning him to an auspicious future of redemptive prosperity, and the bane of the present subverted by a satanic servitude.

Then, the labored respiration rigidly waned commanding the contracting diaphragm to a spiraling descension, edging the exchange of breath gases to an unnerving impasse. The asphyxiated chest wall finally flattened in the culmination of detachment. And then Jim was gone. Jim’s head remained transfixed in an upward position all throughout the violent gasping. Within minutes, there was a shift with a tilt of his head hovering to the right as his chin slouched to his chest in self-effacement. There would be no solace, only the piercing that comes from yearning, regretting, and attesting to death. This memory remains unfading in its fertile depletion. It is a disturbance that invariably taints and questions the value of one’s mortality and it trivializes all that savors the value of living. It would be worn in the finery of a widow’s black garb.

‘I will always remember embracing Jim’s hands throughout those twenty-three days in Room 418 at Calvary in the belief that my affection could traverse through his petrified state.

Like shadows stalking me, I will never consign to vagueness how the skin transmogrified with hematic tumors, the initial one on Jim’s left arm that confirmed the alarming diagnosis, and the one on his chest that subsequently took diabolic form in the successive months. Both germinated in monstrous magnitude and consternation. What was once robust and boundless with unimpaired health, contrived scarcely to a shell of body and mind. It was the waning of something unrelenting like a runaway train that cannot come to a halt. The diagnosis was Merkel Cell Carcinoma, an aggressive and exponential cancer that ravaged Jim’s viscera as well as his endearing spirit. It seems that oncologists are virtuosos at discerning names in the cornucopia of ailments, but research failures when it comes to the deduction of antidotes. This ruthlessness left Jim radically changed and extinguished.

I will always remember embracing Jim’s hands throughout those twenty-three days in Room 418 at Calvary in the belief that my affection could traverse through his petrified state. One cannot comprehend the emotional upheaval magnified by the fulcrum of impending death. It manifests a permanent scarring to one’s psyche. To be relegated to an irrevocable holocaust is frighteningly unimaginable. During the four months that Jim lived with me before entering Hospice, I performed the dutiful role with a genuine faithfulness as I cooked his meals, washed his clothes, prepared him for bed, and accompanied him to cancer treatment appointments. Jim would frequently profess, “I just don’t want to suffer any more than I am suffering now. If they could give me a pill to end it all, I would just take it.”

‘For Jim, death was not a foreign abstraction that is intentionally shunned with its egregious connotations. Instead, it arrived as a concrete daily salutation for two years as it victimized him in an alienated melancholia that engineers from demoralization.

Jim’s face would react in a muted immobility, allude to the omnipresent pain with a weary gesture, reach for his cane, excuse himself, and tap his way a few feet away to the couch where he lay in dereliction. Whenever I asked him to describe the pain, he just sank silent in an unadulterated avoidance with imploring eyes; no rationale could suffice the unimaginable persecution forced upon him. Yet, the disabled gait as he moved about, the menacing aloneness he projected, and his growing detachment from his external world revealed a surrender that could only unfold from being godforsaken. It was something dire that persisted in the consciousness of his being, and the jolt that comes with the stark truth of fading as finality.

For Jim, death was not a foreign abstraction that is intentionally shunned with its egregious connotations. Instead, it arrived as a concrete daily salutation for two years as it victimized him in an alienated melancholia that engineers from demoralization. His sensibility grew responsive to the knowledge that the mind and body would soon fail as compassion abandoned him. Throughout, Jim managed to endure this unthinkable carcinoma with a subdued dignity and a strained cooperative effort with the medical staff. Of course, there were times when he would grow impatient and lash out, but then in the next breath, he would atone gratefully for their care with apologies. Still, there were moments when Jim could manage to requite my tenderness with an engaging smile. Then, the vesper bell would ring, emerging like the pressure of underground water rumbling to convulse, precluding any endearing responses.

‘The touch was fleeting as his hands would then recoil from mine in staggering desperation as the turbulence commenced to seethe, augment, and supersede any depth my pathos could garner.

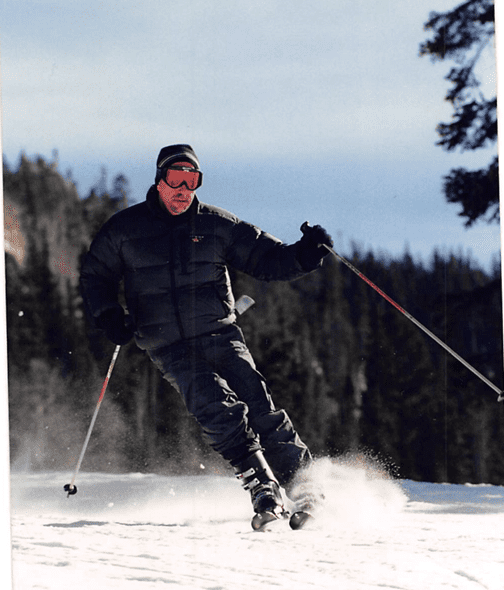

The touch was fleeting as his hands would then recoil from mine in staggering desperation as the turbulence commenced to seethe, augment, and supersede any depth my pathos could garner. The hands that once exuded a gentle warmth, now mellowed cold and damp. The structure of face, once chiseled and aristocratic, illumined a distinct brilliance as he frequently glided in sun-glistened designs on the ski slopes of Lake Tahoe. It was an aura robust in flesh and fervor that phosphoresced as he swam in the crystalline lakes of the west coast. Now, the profile concaves in ashen diminishment, pallid in hue. His speaking voice, once fecund in bass, now faintly tapers in hollow and feeble inflections. The body, stalwart and plenteous in build, solid like a gridiron prototype, metamorphosed in two-dimensional slaughter.

Yet, it is Jim’s benevolent spirit, the lofty essence of his being, that will transcend beyond the transient temporal, and above the desolation of ambiguities and disillusion. Darkness from disease may have devoured my Jim during his earthly dwelling, but God turns his face to Jim as he revels in restoration and renewal in an unmarred hereafter, devoid of suffering and hopelessness.

Credits

Featured Image by Eftodii Aurelia for Pexels

Image of a falling feather for Pexels by Luis Zheji

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

I am a retired high school English teacher from New Jersey. I recently received an online Masters degree in English Language and Literature from SNHU. I am grateful to Dr. Marlen Harrison, who mentored me and inspired me to write from an autoethnographic perspective.