I’d Say I Was a Runner

Author’s Memo

In a single paragraph that visually represents one long thought, “I’d say I was a runner” explores the act of running as a form of self-therapy. By misplacing blame for his mistakes on his body, and by following the stream of consciousness that accompanies a run, the author is, in effect, having an interrupted conversation with himself where he is both the patient and the therapist. Unable to separate his past with his own judgement, but adamant in his path as the right path, he is stuck even while in motion.

In a single paragraph that visually represents one long thought, “I’d say I was a runner” explores the act of running as a form of self-therapy.

In our current social media-driven society, we often use fitness as a visible means of change, of improvement. We shed our old bodies because we want to become someone new and better. But through this piece, the author follows the long thread of a (returning) runner’s thought during a (brief) run to explore the ways in which changing yourself is a method of avoiding who you’ve become. In that way, fitness doesn’t create a new self so much as it attempts to recreate the old one. Only then, with that realization, does the author stop his run.

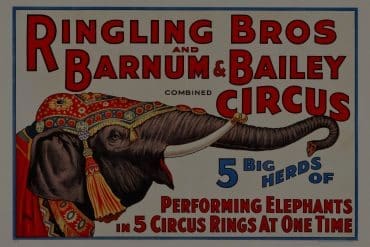

I couldn’t remember the last time I ran. Maybe it was months ago. But the familiar itch of freshly opened pores, as my fleshy legs jiggled with each stride, reminded me that I was out of practice. At least my lungs hadn’t faltered (yet)—my breath steady but apace as I made my way down East Capitol. To be honest, I didn’t fully remember putting on my running clothes and shoes (or, to be more accurate, it was as if I watched myself in amazement as I put both on, wondering what strange force compelled me to choose tonight, of all nights, to initiate this endeavor). There was nothing special about November 13 at 11:03pm, but here I was, running alone, not even compelled by the shame of having to decline an invitation to exercise with a friend—an “accountabili-buddy,” as I liked to call them. I used to run, both track and cross country, in high school. But I had teammates to motivate me, even when I finished second-to-last (and many times last) in our meets. Back then, I practiced daily. But ever since, I’d run sporadically, some months and years more than others. Still, if you asked me to describe myself, I’d say I was a runner (with special emphasis on the past tense). I ran, that’s for sure. And I could still run, as tonight proved—although at my current speed, I was more jogging than anything else. But what about today said “Ok, you’re going to do it! You’re going to renew healthy habits and exercise again.” It couldn’t have been the tightness of my clothes—I’d been feeling that for over a year now, as even my stretch-pants were groaning at the task of both hiding my belly and remaining securely buttoned. And it couldn’t have been the mounting frustrations with my life—those had been bubbling for months and would occasionally overflow, manifesting in dramatic outbursts, rage-fueled declarations of nastiness meant to terminally hurt the feelings of those closest to me, as if bringing others down would keep me company, as if belittling others would create an effective contrast to my own unhappiness. Actually, if I was being honest, I ran subconsciously (or, rather, unconsciously, because the thought flowed like a current deep beneath the surface, more Styx than Potomac, bringing with it memories of a previous person I had once been who had now long since moved on) to return to my past—not to seek out a better future-me, but to relive my glory days, as inglorious to any other person as they might’ve seemed. Because, almost two months prior, I lost a best friend. He had moved on, of sorts, taking with him years of what I considered the happiest times of life. (No, he didn’t die.) He found my bubbling outbursts, as well as my flare for the dramatics, tiresome (a feeling for which, after years of my abuse, I couldn’t blame him). But the method of his separation, the searing brevity of it—“I can’t deal with you”—suggested that he, who knew me best, found such an irredeemable flaw in my character that he could do nothing else but flow southward, a receding memory, never meant for reconciliation, leaving in his wake a nascent truth: that I was just mean and would fade into loneliness. Left with that idea, I spent months in denial. I shored up old friendships, rekindled distant acquaintances, as if to prove that I was still liked by many. But this bruising defeat by a close confidant—someone who, during the pandemic, kept me alive with his company, and who, for years before, was the inseparable other half of our duo—gnawed at me. That might’ve been what forced my hands to lace up my shoes, what set the stopwatch on my phone to record the run (as any runner knew, a run never actually happened unless it was quantified in some way: in time or distance or pulled muscles), what pushed me forward as my feet begged me to stop, and what kept me going, past the Capitol, down the Hill, toward the National Mall. I didn’t stop until, not paying attention, I was almost hit by a car (to be fair, I had continued even when the red hand told me to halt). Facing 7th Street, I decided to turn around and walk home. It was the first decision over the motion of my body that I could confidently say I made solely myself. As I passed by the National Gallery of Art, images of Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life flashed through my memory—a boat on a river floating through a person’s childhood, youth, manhood, and then old age. A passenger on my own makeshift raft, I was adrift without an oar or sail, without direction, desperate to fight the current and return northward, to reclaim fleeting memories by dragging both them and myself to the past, never once looking back. I started to run again, my strides invigorated with some newfound fervor, but not thirty seconds later, I switched back to walking—my legs having loudly protested (but not as loudly as my feet). The Capitol in the background, illuminated in white, resembled the citadel in Cole’s Youth. But I lived behind the Capitol, slightly beyond youth somewhere within a burgeoning adulthood, one in which I would have to deal with my own shortcomings and let the past flow out to the sea. I forced myself to look over my shoulder, beyond 7th Street, at the run I never finished. And although I knew I’d run again tomorrow, at least the new runner’s itch had finally subsided.

Credits

Featured Image by Lucas Favre for Unsplash

Image of The Capitol by Sogand Gh for Unsplash

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Childhood, 1842, Public Domain.

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Trelaine is originally from Hawaii. But, true to form, he saw the line where the sky meets the sea, and it called him, so he currently lives and works in Washington, D.C. He enjoys origami and washing dishes and taking pictures of clouds and sunsets. But never sunrises (he’s not a morning person).

Twitter: @trelaineito

Instagram: @trelaine