Scent and the sense of smell have been of high interest to me since I was a small child. Playing with my mother’s and my very elegant grandmother’s perfumes as a toddler, I soon progressed to reading whatever I could find on fragrances: magazine clippings; books on perfumes and essences, some from authors of classical antiquity; heavy volumes of chemistry and perfumery later on. The fascination with its history prompted me to collect & study a large sum of vintage fragrances, essential oils and synthetic materials for several years.

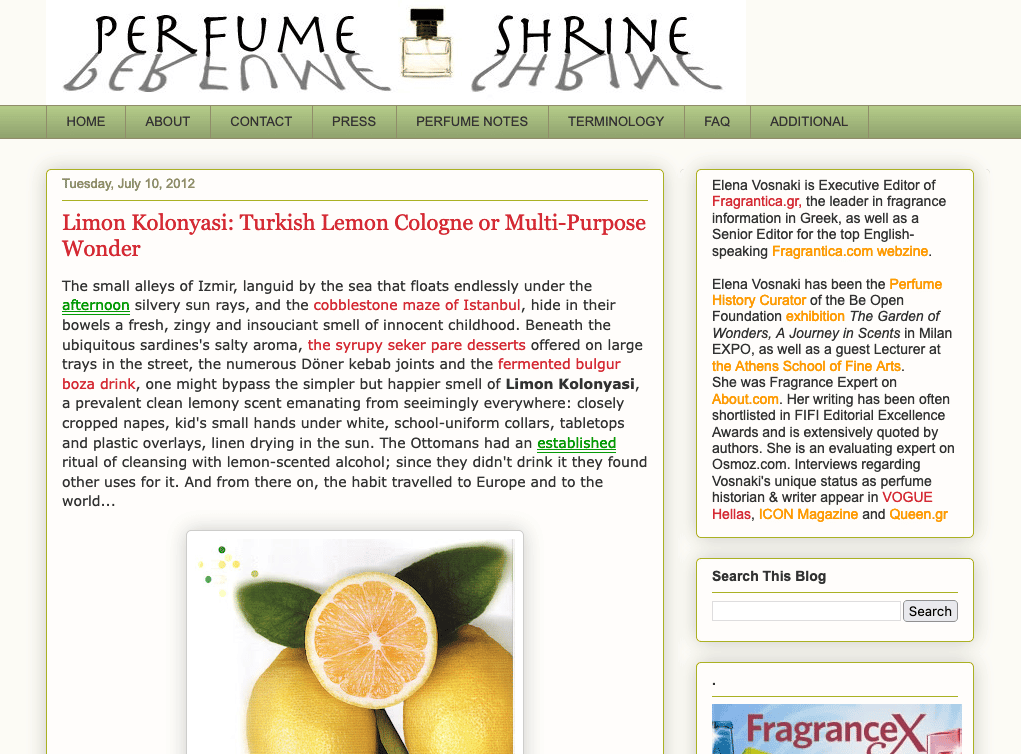

Elena Vosnaki, Perfume Shrine

The cultural roots of my family trace the borders of Byzantine history, with many of them hailing from parts of the Byzantine Empire which are no longer under Greek dominance or preponderance. These were peoples who lived in a vastly nuanced world of the senses, with a rich tradition in both food, cosmetics, and fragrances, and all of my relatives appreciated those tales of olfactory and aesthetic decadence without shame or guilt. There was no Puritan abhorrence of scent as an element of the devil; even the church was full of smells, holy and secular as well; I enjoyed it very much indeed.

Men indulged as well as women, and because my grandmother was Greek born in Constantinople/Istanbul, she was well familiar with the hosting habit of Limon Kolonyasi, the process of greeting guests with lemon cologne for their hands, and of cleaning every surface with big vats of this clean-smelling alcoholic cologne.

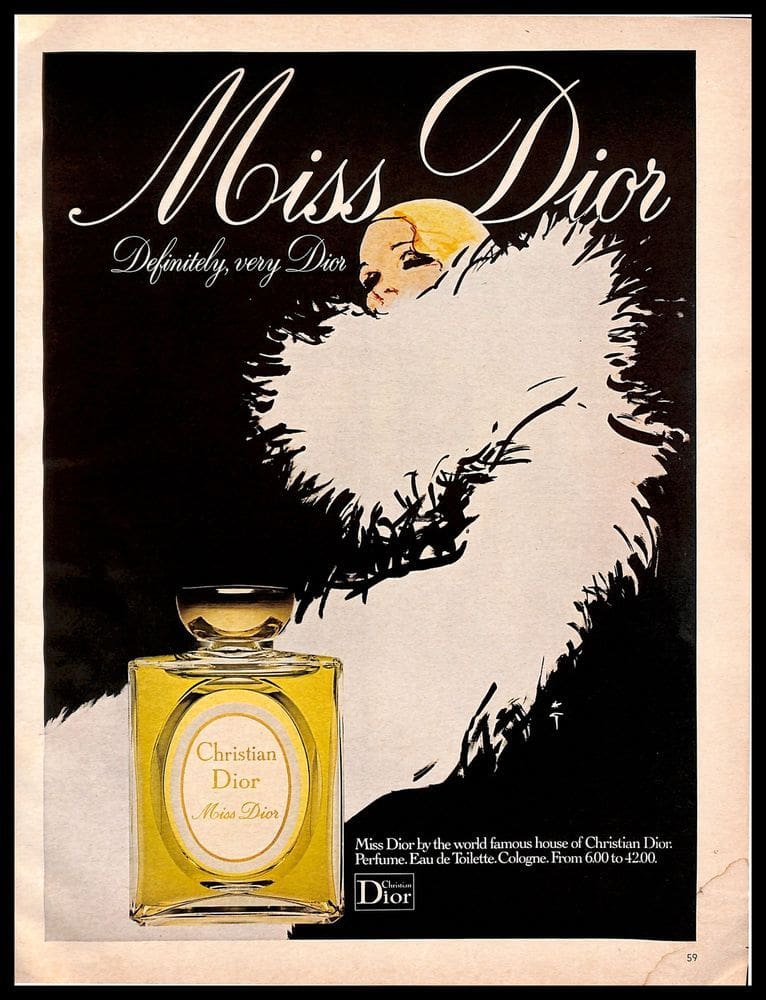

At the same time, because of her family’s wealth and her own work (she was later the first female representative of an international brand in Greece), she was importing her clothing designs from Paris, and alongside les patrons, there came the fragrances as well! I distinctly recall her deliciously smelling of Madame Rochas, YSL Rive Gauche and the classical 1947 Miss Dior. The newer scent and its variations have absolutely no relation to the haughtiness and sensuality of the original, alas. My mother and my father also wore magnificent fragrances, of which let me only quote in passing Guerlain Habit Rouge, Gres Cabochard, and Dioressence, which seemed regal poised atop the vanity to my childish eyes.

These cultural signposts were instinctively impressive, and they mingled with tales from abandoned homes in the Near East: from Ismir (Smyrna) where my paternal grandfather hailed from, from Istanbul, from Andrianople…. These tales were invariably a lesson in aesthetics (they were the reference of “the good life”, as they were cosmopolitan cities with very mixed cultural minorities) and also in history, as they were so intermingled with political incidents in that spot in the world which seems constantly in some sort of turmoil, the eastern Mediterranean.

I suppose it was all pre-mapped out for me in a way, but like Indiana Jones famously said “there’s no X marking the spot.” I found the way to being a perfume historian while enjoying myself.

My childhood bedtime story was Herodotus’s Historiae. I absolutely adored that book full of heroic and tragic incidents in the clashing of two eminent civilizations, the Persian (and its incorporating of all the previous ones they domineered upon) and the ancient Greek one. I still recall the leather bound tome my mother and father first read tales from, and later I came to read from it, too. My mother taught me to read ahead of school, at the age of 4, so one can say that history was a natural course. And because I was so immersed in both history, bound in good-smelling leather, no less, and in beautiful and evocative little bottles around me as playthings, I guess it needed no further prompting. It was within my blood before I could think about what I wanted to do with my life!

But of course it only took full shape when the internet arrived in my life. I had amassed a huge list of historical figures and what their preferred scents were, from the Romanov’s choices of perfume, to what Hollywood stars of the Golden Era loved to wear. It went online, people quoted me and shared the info on fragrance fora. It was delicious for me to discover that these places existed in the first place, meeting people from all over the world, and sharing a common interest and passion. And when it was known I was an archaeologist and historian, interest went rampant and I started getting propositions of professional work too: research, copywriting, articles, you name it.

So I suppose it was all pre-mapped out for me in a way, but like Indiana Jones famously said “there’s no X marking the spot”. I found the way to being a perfume historian while enjoying myself. Here are a few of my articles to introduce you to my work and culture:

- Turkish Lemon Cologne

- The Indefinable Allure of a Signature Scent

- Perfume Acting as a Time Capsule: Why We Will Forever Love What We Once Loved

- Mythology Series: Pomegranate

The most important element that was revealed to me is that some of the olfactory landscapes that emerged from fragrance first, travel and lived experiences later, have shaped my appreciation. For instance I came to love “dirty” musks, which were introduced to me via perfumery first, especially when studying the natural and synthetic raw materials themselves. Now I tend to distinguish them in the fur of some animals, or the nuance left in a lived-in house or building!

My cultural influences majorly involved the eastern Mediterranean, a melting pot of cultures: Greek, Ottoman, Italian, Hebrew, Slav and Armenian. These have also interested me from a historical standpoint of the ethnic preponderances for specific scents in my research, as there were many libraries I could visit for raw materials: newspapers, official letters, periodicals.

Nevertheless, traveling to Europe as a teenager as well as to other continents as a student and young adult, also informed my perception of scent. There was the first time I was met with the almost chaotic phenomenon of “the American drugstore”, so spoiled for choice, so many assorted things! It was so very different from the experience of the Greek or French pharmacy, with their small space and tightly arranged shelves, often yielding under vats of herbs with Latin inscriptions on their exterior… The women were also very different to me; they embraced an aesthetic of very “done”, meticulously coiffed and manicured to within an inch of their lives; it gave me a feeling of anxiety, of not meeting up a set criterion of grooming, whereas more “natural” has always been a European aesthetic. American perfumes reflect that I suppose, even to this day, though the intermingling of globalization and the Net has blurred such lines.

Photo by Wei-Cheng Wu on Unsplash

I can also never forget the seemingly yeasty smell of the air in Singapore and Bangkok, it hit you like a ton of bricks stepping down the aircraft, coupled with the humidity which permeates everything. Or, of the fact that people in Germany consumed apple juice more than water (which is easily explained by the fact that their tap water is amazingly hard, i.e. with a high percentage of dissolved minerals, largely calcium and magnesium).

These lived experiences are hard to shake off. And they do tend to come up whenever I think of smells, because they inform my perception, so in that sense they become autoethnographic. When I smell a purely “American” perfume I tend to expect something clean and impressive in terms of claiming an area of a square foot around the wearer. When I think of Far Eastern scents I expect the woody and airy incense of the temples of those regions, or of the humid jungle seeping into the mix. Sometimes the final impression is juxtaposed with those primal expectations, so the aesthetic approach in writing follows two paths, one of fruition and one of refusal.

But the most important element that was revealed to me is that some of the olfactory landscapes that emerged from fragrance first, travel and lived experiences later, have shaped my appreciation. For instance I came to love “dirty” musks, which were introduced to me via perfumery first, especially when studying the natural and synthetic raw materials themselves. Now I tend to distinguish them in the fur of some animals, or the nuance left in a lived-in house or building! Here are some of my thoughts on cultures:

- Why French (and European) people grow up to love scents while Americans don’t

- Musk Series 1: A Cultural Perception of Musk

In narrative inquiry we come across subjects shaping the matter through their own “digestion” of facts, so to speak. It’s a very interesting approach to fragrance especially, because beyond the scientific facts, which can only be unlocked with gas chromatography and a mass spectrometer, personal tales give a more telling and more engaging sense of what any perfume is about.

Personally, and I might be wrong, I do not believe that it is even possible to entirely exclude one’s own approach to inquiry. There can be no author-evacuated history, because the historian is a product of their own times, they belong to a school of methodology, etc. This is why history is not an exact science like chemistry, but it is also what makes it fascinating; it’s different reading different books.

One is always in motion with history, events of the past are in a constant interaction with the present. A monumental time such as the October Revolution of 1917, for example, can be examined under a Marxist methodology, or the point of view of Les Annales (the Marc Bloch and Lucien Febre school of thought), two rather different approaches. But besides that, even what subject one chooses to immerse themselves in is part-and-parcel of the author. This is similar to how journalism works, working by omission is a major telling sign of how the medium responds to specific events, though in historiography no decent historian would purposefully omit evidence and raw sources, of course.

Image by Steffan Lewis from Pixabay

In narrative inquiry we come across subjects shaping the matter through their own “digestion” of facts, so to speak. It’s a very interesting approach to fragrance especially, because beyond the scientific facts, which can only be unlocked with gas chromatography and a mass spectrometer, personal tales give a more telling and more engaging sense of what any perfume is about. We can more easily relate to an author telling us that a fragrance reminds them of the first time they opened a can of tinned pineapple and of the metallic-green fruity scent hitting their nostrils, than of them telling us that something contains allyl amyl glycolate.

I believe that for that reason, because we communicate fragrance to the layman and the hobbyist, not the professional chemist, the recounting of a tale, informed with factual nuggets, of course if we want to retain objectivity and credibility, is an essential part of our work. As a perfume author and historian I have always tried to tread this delicate balance where there is enough engaging and lived-in experience interlaced with scientific approaches that put historical context to it. In my opinion, this gives value and originality to the exposition, because on the other hand too much personal stuff can feel like reading one’s private diary, fun in a way, but who wants to snoop into gossip all the time?

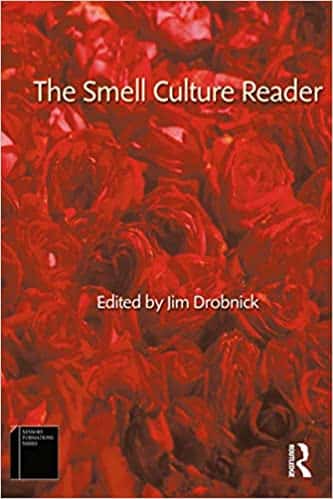

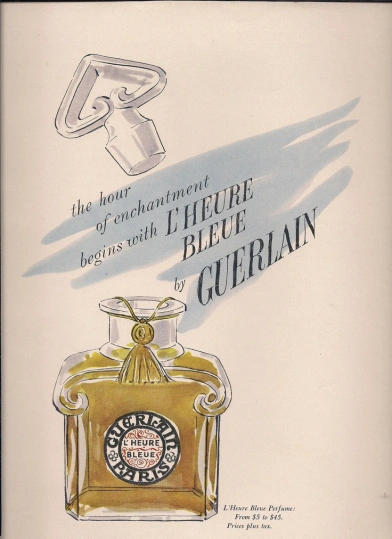

Someone who grew up in the Appalachians in the 1950s has a totally different fond recollection of milk and grass, which shaped their childhood, than a child of the urban 1980s who grew up on Play Doh. Such observations can explain why a scent of the 1910s such as the very French L’Heure Bleue by Guerlain can feel alien to the former, but somewhat familiar to the latter; they share benzaldehyde and almondy heliotropin.

It’s also important to delineate the author’s viewpoint so that readers can better grasp their point of view. When I talk about a “classical” elegance, I refer to classical from the point of view of the classical civilizations of Rome and Greece. Someone else, not necessarily in my shoes, might conflate classical with French fashion, or with something archaic and therefore obsolete. Who knows? So it’s important to lead the reader into where the author comes from, culturally, aesthetically, historically.

Sometimes even the age of the author plays a major part in what they perceive as pleasant smell-wise. This was beautifully highlighted in an article contained in the Smell Culture Reader, a collective work edited by Jim Drobnick (2006, Routledge, ISBN-10. 1845202120). Someone who grew up in the Appalachians in the 1950s has a totally different fond recollection of milk and grass, which shaped their childhood, than a child of the urban 1980s who grew up on Play Doh. Such observations can explain why a scent of the 1910s such as the very French L’Heure Bleue by Guerlain can feel alien to the former, but somewhat familiar to the latter; they share benzaldehyde and almondy heliotropin.

My own body of writing, which is rather unique in that it comes from a nation with tiny representation in international writing on scent, is therefore always careful in explaining these affinities, delineating cultural habits and customs, and communicating them to a reader that is probably not familiar with them, I take nothing for granted because I recognize that people from all over the world do not share the same customs or memories. I suppose that is the enriching part, we all borrow from each other, and thus our palette is endlessly expanding. Here are some of my additional thoughts on this:

- Fragrance Intertextuality: Homage or Creative Dialogue?

- The Perfume Magazine December 31, 2012: Ways of Seeing Perfume Advertising & the Case of Chanel No.5

Very few people in the world are authentic experts on the aesthetics, the artists, and the artists’ historical times and professional achievement. Elena Vosnaki is one of this very small group, and her knowledge is jaw-dropping, detailed, art historically contextualized, and encyclopedic on the natural raw materials that make perfumes such compelling works of art.

Chandler Burr, The Emperor of Scent

There are various trails of scent I follow these days, a bit of a greyhound. The fragrance world has expanded exponentially since the days when I was a teenager, with the market rising to thousands of bottles launched each year, but there are also various innovations in relation to scent and scent perception, especially in digital transliteration and organization of scent, and in scent marketing, i.e. attributing a scent to a brand.

In my capacity as a writer, and also a copywriter for brands, I focus on appreciating newer and older fragrances in the designer and niche categories, but what differentiates my work, I guess, is that I try to always bring a contextual axis to this appreciation and highlight elective affinities, so to speak. My work resembles that of a fashion historian, who always examines the underlying influences of any designer, the evolution of the craftsmanship, and the interrelation with politics and history of the times, when talking of any design. It’s the same with fragrances.

Historically, the reconstitution of ancient mixtures has always fascinated me, ever since reading in Egyptology about the intricate wax melts people used for scenting their wigs. My focus, due to my heritage and upbringing, has been the Mediterranean and in many ways it is the portal through which all the rest of the Western world emerged, so it’s like tracing those paths.

Right now, I’m working on a book of poetry that mixes scent with verse, inspired by the works of local poet, Christos Koukis who is the curator of the Crete International Poetry Festival. I also worked on a project with Sandrine Videault, the famous French perfumer who resided in French Polynesia, to rebuild the mix of the infamous Chypre recipes of antiquity for the National Archaeological Museum of Greece. A potential collaboration with the state of Cyprus in a later time was also in our sight. This came a few years after the Pyrgos-Mavrorahi excavation on the island of Cyprus, which revealed the world’s oldest perfumery lab and factory. Sandrine had already worked with Egyptologists for the reconstitution of the ancient “kyphi” incense for the Cairo Museum, so she was a perfect fit for my work. The recipes for “chypre” scents awaited, and my proposition was received very enthusiastically. We worked closely and unearthed information about how the chypre tradition was inspired by the land, and of how it influenced later perfumers of the Middle Ages. However Sandrine’s untimely and sad death brought an end to this ambitious project. Maybe one day I’ll pick it up again.

CHYPRE: “the name of a family of perfumes that are characterised by an accord composed of citrus top notes, a middle centered on cistus labdanum, and a mossy-animalic set of basenotes derived from oakmoss.” via Wikipedia

Here are a number of links to my writing about Egyptian elixirs and classical chypres.

- The Mystery of Egyptian Elixirs & The Story of Sacred Kyphi Perfume

- Chypre series 1: The origins

- Chypre series 2: Ingredients

- Medieval Chypre Scents: Oiselets de Chypre or the Mysterious Cyprus Birdies