Syrian Identity and Academic Self: Emerging Research or Ruthless Methodology?

Author’s Memo

As a Syrian, the foundational years I spent studying architecture in my homeland significantly molded my identity. However, it was during my PhD studies in the UK — where I explored heritage policy and the intricacies of managing heritage properties — that my academic identity truly flourished. This was further enriched by an in-depth understanding of research methodologies.

Relocating from Syria to the UK to embark on my journey as a higher education lecturer occurred during a period overshadowed by significant conflict. This transition represented more than a mere professional shift; it became a profound odyssey of personal growth and self-realization. As I settled into the UK, immersing myself in its academic landscape catalyzed an inner metamorphosis. Along this path, I encountered pivotal moments that not only sculpted my academic identity but also sharpened my research methodologies and strategies.

A standout aspect of this journey was my growing affinity for Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). This includes oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge concerning nature and the universe, and traditional craftsmanship. My personal connection to these traditions spurred my exploration into their practice among displaced Syrians in the UK. This exploration necessitated a delicate equilibrium between my Syrian identity, my academic persona, and the stringent demands of research ethics and methodologies.

Within the realm of qualitative research, scholars often find themselves trapped in debates regarding positionality and objectivity. The archetypal academic setting reveres the image of the researcher as an impartial sentinel. Here, the researcher stands apart, merely chronicling the tales and trajectories of communities invariably labeled as the ‘other’. While there’s undeniable value in this distanced observation—particularly when a deep immersion into a community isn’t plausible, or when the research focus lies elsewhere—this viewpoint also runs the risk of perpetuating an ‘us-versus-them’ dichotomy.

‘This two-part article doesn’t aim to be an exhaustive guide for researching communities deeply affected by trauma, especially when the researcher—myself in this case—is emotionally and experientially tied to that trauma.

In my journey, autoethnography emerged as a liberating nexus between the personal and the scholarly. It facilitated an exploration that was introspective yet expansive, presenting a renewed perspective that defies traditional dichotomies. Rather than standing at the periphery as a mere observer, I found myself at the heart of the research, an active participant weaving my own narratives into the larger fabric. Through this process, I came to understand that our collective mosaic of knowledge becomes richer, more vibrant, and immeasurably deeper when we intertwine our personal threads with those of the communities and individuals we study. Naturally, no methodology is without its imperfections; the deep intimacy cultivated by autoethnography can also render it vulnerable to criticisms of subjectivity. It is here that a robust ethical framework and rigorous methodologies can serve as invaluable counterweights.

As Carolyn et al. (2011) insightfully state, autoethnography “is an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyze personal experience in order to understand cultural experience. This approach challenges canonical ways of doing research and representing others…” This perspective deeply resonates with my own journey. Through autoethnography, I’ve come to recognize and reflect upon my own biases, viewing them as tools for nuanced storytelling rather than flaws to be concealed. This method also allows me to weave my voice into the narratives, be they joyous or sorrowful, shared with me by fellow Syrians.

‘Rather, this narrative seeks to illuminate a personal reflection that sparked a unique line of inquiry, ultimately leading to an innovative exploration within my research project.

This two-part article doesn’t aim to be an exhaustive guide for researching communities deeply affected by trauma, especially when the researcher—myself in this case—is emotionally and experientially tied to that trauma. Such a complex subject deserves a thorough study of its own. Rather, this narrative seeks to illuminate a personal reflection that sparked a unique line of inquiry, ultimately leading to an innovative exploration within my research project.

In my academic pursuits, I explore a comparative analysis of Syrians engaging with Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) amidst two distinct crises. The latter, the Covid-19 pandemic, unfolded in their newfound home, the UK, and commanded global attention. This juxtaposed starkly with the preceding crisis, one that remained largely in the shadows — the intense hardships endured in confinement during the Syrian conflict. As someone who has intimately navigated both terrains, I find myself deeply attuned to the experiences of many Syrians. I sincerely feel every burst of laughter, every tear shed, and every moment of resilient pride. These once-concealed emotions, buried beneath layers of anguish, have surged to the forefront in my research. I warmly invite you to journey through this deeply personal academic exploration with me.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ataa Alsalloum, School of Architecture, University of Liverpool, 25 Abercromby Square, Liverpool, L69 7ZN, UK. Email: at***@**********ac.uk.

‘In my journey, autoethnography emerged as a liberating nexus between the personal and the scholarly. It facilitated an exploration that was introspective yet expansive, presenting a renewed perspective that defies traditional dichotomies.

Syrian Identity and Academic Self: Emerging Research or Ruthless Methodology?

(part 1 / 2)

In March 2020, as the UK declared its inaugural Covid-19 lockdown, my thoughts spiraled back to Syria, specifically to February 2012. Vivid recollections of intense battles and skirmishes that had erupted right on my street in Homs city flooded my mind. Trapped in our home, my parents, my daughter, and I grappled with palpable fear, confined for what felt like an interminable span. When circumstances finally compelled us to venture out, an eerie stillness hung over the streets. Landmarks lay in ruins, the once-familiar cityscape now grotesquely distorted. Though we harbored hopes of returning within weeks, perhaps months, reality proved starkly different. Four agonizing years elapsed before we could even contemplate a visit. By then, the heartache had compounded – the sad demise of my mother and our cherished home reduced to rubble. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The road leading to the author’s residence in Homs, Syria

About a decade later, I find myself ensconced at my desk in Liverpool, penning thoughts on intangible cultural heritage, war, and the Covid-19 pandemic. My mind invariably drifts back to that defining moment, encapsulating all the uncertainty and trepidation of the times ahead. As of August 2024, we’re barely on the cusp of resuming a semblance of normality. Yet, there exist corners of our world where the daily struggle for survival eclipses all else. Some areas still lack access to the Covid-19 vaccine. And tragically, even regions once thought insulated from conflict, like Europe, haven’t been spared, as evidenced by the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian strife.

‘Through this process, I came to understand that our collective mosaic of knowledge becomes richer, more vibrant, and immeasurably deeper when we intertwine our personal threads with those of the communities and individuals we study.

Wars, once they fade from immediate media attention, often drift into the pages of history books. However, for those scarred by their impact, the pain remains ever-present. The Russian-Ukrainian, Yemeni-Saudi, and Syrian conflicts are poignant reminders. Such conflicts exacerbate the already unstable state of our world, leading to the displacement of countless individuals, left to navigate the repercussions alone. Throughout my observations, I’ve discerned that adversity can reveal both the brightest and darkest facets of humanity. In this article, I aim to emphasize the former, while also shedding light on potential avenues to mitigate the latter.

In 2020, I embarked on a research endeavor, seeking to document the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) practices embraced by fellow Syrians resettled in the UK. These include oral traditional, performing arts, social events, knowledge related to nature and universe, and handcraftsmanship. However, the Covid-19 pandemic temporarily forestalled our efforts. During my interactions with these individuals, I discerned a trend: many had turned to our shared ICH practices as a beacon during the pandemic.

Poignantly, some of these very practices had been their solace during Syria’s armed conflict, when circumstances held them captive within their homes. The narratives shared reignited my own memories. Amidst the Syrian conflict’s-imposed isolation – a period marred by fear, uncertainty, and dwindling essentials like food and electricity – my late mother and my father, back in 2012, sought refuge in our rich heritage. They educated my daughter, sharing age-old poems, teaching traditional paper-and-pencil games, and regaling her with tales of their past and the customs of our village. These heartfelt recollections catalyzed my deeper exploration.

‘Naturally, no methodology is without its imperfections; the deep intimacy cultivated by autoethnography can also render it vulnerable to criticisms of subjectivity. It is here that a robust ethical framework and rigorous methodologies can serve as invaluable counterweights.

In response to these challenges, I felt compelled to gather narratives from Syrians who’ve found refuge in the UK. It’s essential to acknowledge that many other migrant communities in diaspora have their own tapestry of stories, both paralleling and diverging from the Syrian experience. These stories hold immense value, as aptly described by Maya Angelou, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” It’s my earnest desire that my research serves as a beacon for those intrigued by the nuances of ICH, especially as it pertains to communities in diaspora.

In the heart of my inquiry into the ICH, I consciously chose to steer clear from asking about their experiences in Syria. Ethically, it felt imperative to not pry into potential traumas, perhaps also influenced by my personal challenges that I was still wrestling with. My journey to the UK differed vastly from theirs. While they sought asylum and later managed to bring their families to safety, I came on a working visa, a position of undeniable privilege. Furthermore, the religious dimension added another layer to our differences; while the community predominantly identified as Muslims, I was a Christian. This duality of self, as a Christian and a researcher, in itself might necessitate another narrative altogether.

However, my initial intent to center our discussions around the traditions they upheld during lockdown amidst the conflict inadvertently opened up channels of communication that exposed me to their varying circumstances. At times, their political perspectives and views surfaced, areas I had been consciously avoiding in my research. The narratives weren’t just about traditions, but about resilience, beliefs, and the very fabric of their identities.

‘In 2020, I embarked on a research endeavor, seeking to document the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) practices embraced by fellow Syrians resettled in the UK. These include oral traditional, performing arts, social events, knowledge related to nature and universe, and handcraftsmanship.

In my quest to identify the most effective methodologies, I was struck by an unexpected realization: many Syrians, much like the general public and even some professionals, remain unfamiliar with the term ICH (Intangible Cultural Heritage). This observation underscores a broader gap in public knowledge within the heritage field of studies. Given this context, my initial course of action was clear. I needed to embark on a process of education. With the challenges presented by Covid-19 restrictions, I pivoted to the digital domain, launching an online lecture. I started by exploring the broader context of Syrian heritage, and gradually narrowed the focus, introducing and elucidating the concept of ICH.

During the preparatory phase of the lecture, I embarked on a deeply personal journey. As I sifted through photographs of Syria’s historic structures, many now reduced to ruins, I was consumed by nostalgia. The emotions stirred by these images brought clarity to a dilemma I had wrestled with for years: my past reluctance to immerse myself in Syrian heritage and the ever-present unease about whether I might ever set foot in Syria again. This poignant sense of loss, intensified by lingering melancholy, had deterred me in the past. Yet, I must acknowledge that this engagement has served as a therapeutic salve, alleviating some of my internal conflicts.

‘However, my initial intent to center our discussions around the traditions they upheld during lockdown amidst the conflict inadvertently opened up channels of communication that exposed me to their varying circumstances.

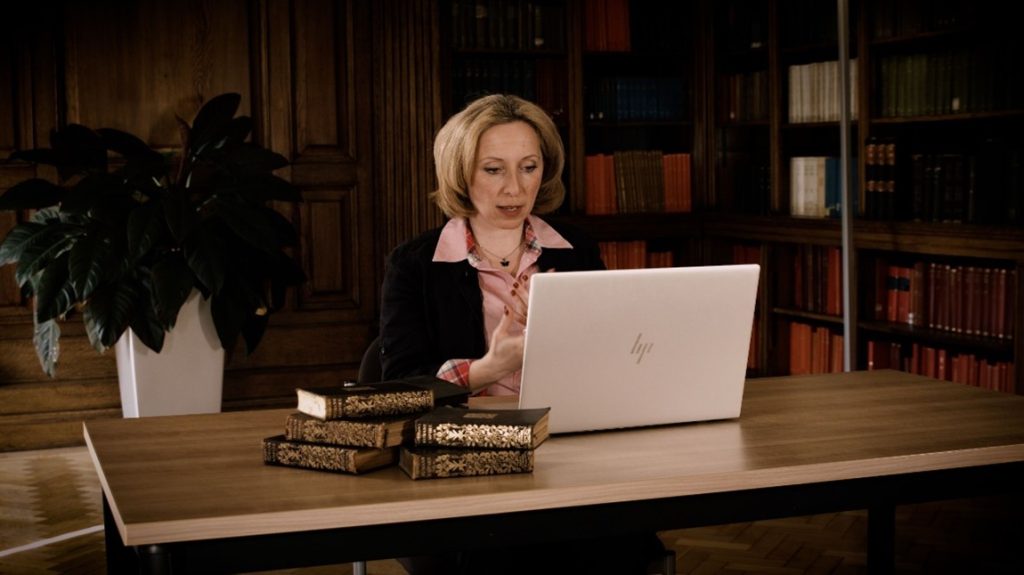

I selected a beautiful room in our Georgian building, adorned with ancient books, as the venue for my lecture, primarily for its ambiance and reflection of knowledge. (See Figure 2). As I sat at the table in the room’s center and began delivering my talk, a profound sense of pride swelled within me. Disseminating this knowledge in Arabic, my mother tongue, felt simultaneously like a blessing and a privilege. Under different circumstances, had I been in Syria during that period, such an opportunity might have remained an elusive dream.

The depth of the experience was magnified by the diverse assembly of attendees. Among them were some of my own PhD students and departmental colleagues for whom Arabic was a mother tongue. Although not all were of Syrian origin, their presence highlighted the universal appeal and intricate narratives surrounding heritage. To foster interaction with the audience, I incorporated traditional proverbs for them to complete. As I displayed those slides, I was elated to hear distinct Syrian voices and accents. I could discern the regional nuances, pinpointing where in Syria they might be from — a sensation I hadn’t felt in over five years.

Figure 2.

The author delivering an online lecture at the SOTA library, Liverpool, UK

‘In my quest to identify the most effective methodologies, I was struck by an unexpected realization: many Syrians, much like the general public and even some professionals, remain unfamiliar with the term ICH (Intangible Cultural Heritage).

My elation persisted when an attendee from Oman shed light on a viewpoint I feared we Syrians might have overlooked. He recounted his visit to Syria a few years prior to the war, expressing admiration for the harmonious society he witnessed. He asserted that other Arabic nations with diverse populations could take a cue from Syria, noting how Muslims, Christians, Druze, and others had coexisted peacefully for millennia. Reflecting on his observation, pride surged within me, but it was quickly overshadowed by a pang of sorrow. I recognized that during the conflict, religious differences drove wedges between individuals based on their political affiliations.

This ignited an urgent query within me: Can Syrians, given the weight of recent history, ever live in harmony again, whether in Syria or abroad? Is it possible for them to transcend their grief and losses to embrace reconciliation? Could heritage or culture serve as the adhesive that binds them anew, or is this aspiration a mere mirage, elusive and distant? As I pondered, many voices in the Zoom call resonated with these thoughts, underscoring the idea that ours is a unique society, one that has historically thrived amidst religious diversity and varied interests. However, the pressing question still lingers in my consciousness.

‘Can Syrians, given the weight of recent history, ever live in harmony again, whether in Syria or abroad? Is it possible for them to transcend their grief and losses to embrace reconciliation?

The lecture acted as a pivotal catalyst, akin to the first drop of rain signaling an imminent downpour of opportunities. This venture facilitated connections with diverse individuals online and later in person. As the grip of the Covid-19 restrictions loosened, I was warmly invited to the Syrian-British Cultural Centre (S-BCC) in Liverpool. This organization, besides aiding Syrians residing in the city and its outskirts, also manages a weekend Arabic school. Remarkably, I’ve forged deep bonds with two of its members, who have now become my closest confidants. It’s an ironic twist of fate—had I remained in Syria throughout my life, our paths might never have crossed.

Through the S-BCC, I successfully recruited 20 participants for interviews. As my network broadened, an additional 8 participants entered the conversation via various connections. Engaging with my fellow Syrians transformed into a revelatory journey. While some were initially unfamiliar with UNESCO’s distinctions between tangible and intangible heritage, their inherent recognition of Syria’s abundant heritage was unmistakable. As our discussions deepened, the concept of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) struck a chord with many. They shared a multitude of activities reflective of Syrian traditions, adapting and integrating these practices both from their homeland and within their new environment in the UK. A palpable sense of camaraderie permeated the group; they consistently supported one another, celebrating triumphs and empathizing with grievances.

The lockdown, brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, presented another layer to our discussions. While many dodged the sensitive terrains of their escape from Syria and subsequent journey to the UK, when prodded, the intensity of their stories was profound. Each account could be a standalone epic, narrating tales of resilience, determination, and the indomitable spirit of survival. Observing their tenacity, I felt humbled by my own comparatively untroubled journey to the UK.

‘Could heritage or culture serve as the adhesive that binds them anew, or is this aspiration a mere mirage, elusive and distant?

The world widely reported on the mental health challenges, isolation, and anti-social behaviors stemming from the pandemic’s lockdowns. However, for many of the Syrians I spoke with, this confinement paled in comparison to their experiences during the conflicts. Instead of despair, they channeled this period into rejuvenating familial bonds. Families congregated, prayed together, prepared elaborate traditional dishes, and even crafted Syrian decorations, filling voids left by the UK market. This time also became a repository of stories, as parents relayed their life narratives to younger generations, ensuring the continuation of a shared cultural memory.

Engaging with these families, I felt a deep resonance. Every laugh and each tear shed found a reflection within my own soul. This prompted a personal introspection, and I soon found myself sharing my ICH stories with my daughter. I regaled her with tales from our village and the festive times during Easter or Christmas. Although her memories of these events were hazy, I hope that through these narratives, I can reignite her connection to our heritage. Initially, as a researcher, my aim was to have a positive influence on the community. Yet, I realized they have equally, if not more, impacted and enriched me. In this journey, as stories unfolded and emotions intertwined, the resilience of the human spirit shone through. The Syrian diaspora, with its rich tapestry of experiences, not only preserves its heritage but adapts and evolves, ensuring that its legacy remains vibrant for generations to come.

Syrian Identity and Academic Self: Emerging Research or Ruthless Methodology?

(part 2 / 2)

As discussions around interview questions unfurled, a poignant narrative crystallized. The individuals I engaged with expressed their anxieties and aspirations concerning the perpetuation of our cultural legacy. The heart of their apprehension was the scant attention our abundant heritage received in mainstream English schools. While weekend Arabic schools did impart lessons in language and Islamic teachings, the rich mosaic of our traditions and cultural nuances often took a backseat. Their concerns resonated deeply within me, accentuating an urgent call to action.

Spurred by this shared sentiment, I was inspired to curate a trio of online workshops designed especially for school children. Understanding the varied developmental stages between younger and older children, I developed three differentiated workshops. Two workshops catered to the imaginative minds of children aged 7 to 11 with simplified tasks, while another targeted the more discerning 11 to 16 age group. This activity prompted a reflective journey, drawing parallels to my heart-to-heart discussions with my daughter, who, as of 2020, was on the cusp of her 17th birthday.

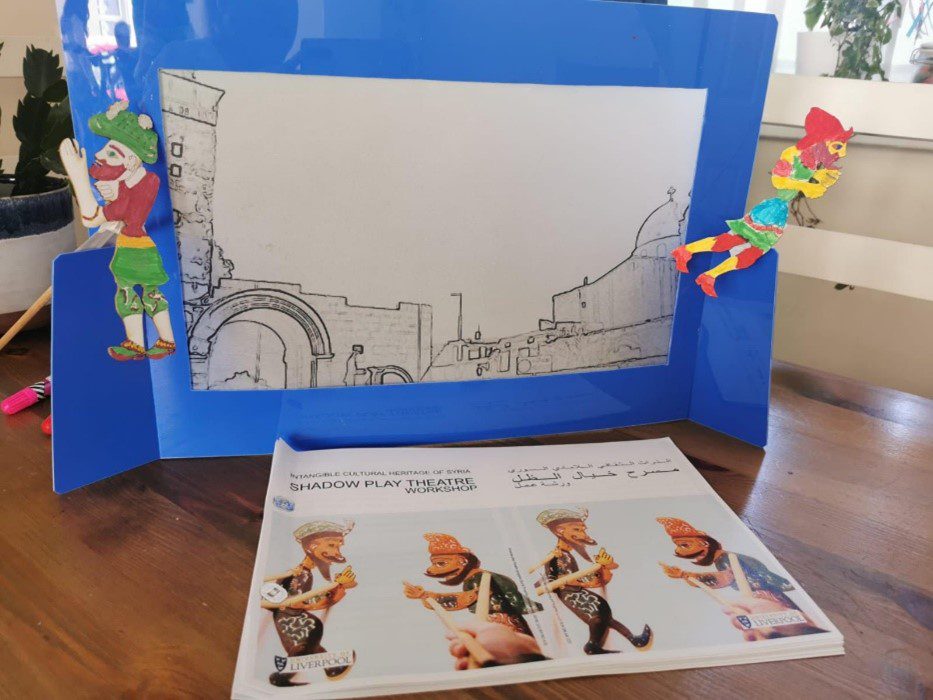

A workshop designed for children aged 7 to 11 highlighted the Syrian tradition of shadow play theatre, a tradition that has been on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding since 2018. As I contemplated a gripping narrative, I turned to my daughter, seeking her perspective on what she wished to understand. Her response was illuminating. She expressed a desire for people to recognize that Syria’s heritage is home to both magnificent churches and mesmerizing mosques. Interestingly, her sentiment echoed a point which was previously highlighted during the online lecture, even though she hadn’t attended it. In her recollection, both places of worship were universally revered and frequented, regardless of religious distinctions.

‘As I pondered, many voices in the Zoom call resonated with these thoughts, underscoring the idea that ours is a unique society, one that has historically thrived amidst religious diversity and varied interests.

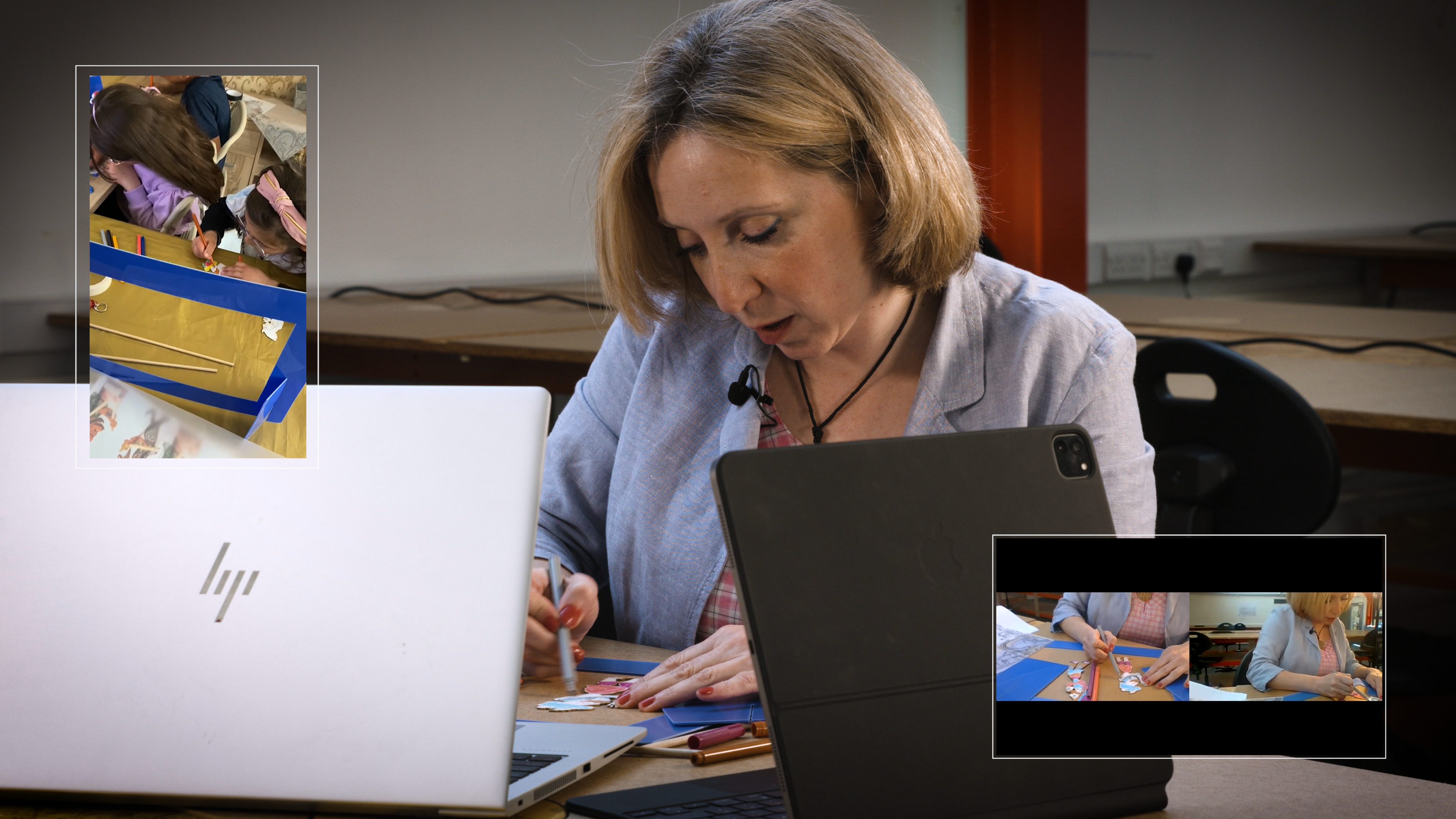

Guided by her recollections, I created a transparent screen portraying the iconic church and mosque of Old Damascus. Her most vivid memories of Old Damascus hinged on the bustling bazaar, redolent with the scents of aromatic spices and roasted nuts, epitomizing authenticity. Her recounting left me astounded, especially considering she was a mere 13 years old during our last sojourn in Syria. Together, we weaved a narrative, framed as a dialogue between the traditional characters, Karakoz and his astute companion, Eiwaz. She played an instrumental role during the online workshop, which I delivered from one of our architectural studios at the University. (See Figure 3).

In the subsequent workshop, aimed at the same age group, I explored the realm of traditional storytelling, known as ‘hakawaty’. My fortune led me to a young woman who was preserving this traditional Syrian art form. I first became acquainted with her through her evocative YouTube videos, which later led to her participation as one of my interviewees. This spirited storyteller, also a single mother to a five-year-old daughter, has carved her niche in the UK. Collaboratively, we crafted a tale cantered on the revered Islamic tradition of Ramadan and the practice of fasting. Our narrative unveiled the spirit of communal support during this holy month and illuminated the role of the ‘musaher’. This figure, deeply ingrained in Syrian tradition, would navigate the old streets, rousing people for ‘suhur’ with mellifluous songs and rhythmic beats on the ‘daff’, typically around the early hours of 4 or 5 am.

Figure 3.

Work from a child during the shadow play workshop, shared by parents

What I found most admirable about this storyteller was her commitment to the aesthetic essence of ‘hakawaty’. She would wear traditional dresses and the ‘tarbush’ while narrating, thereby challenging the customary image of an elderly male ‘hakawaty’, who would often regale stories in public cafes. Her defiance and reverence for tradition struck a chord. At times, I saw reflections of my younger self in her— reminiscent of a time a decade ago when I, too, navigated the challenges of being a single mother, seeking refuge from war and societal judgment, in pursuit of a dignified life. Today, I take immense pride in mentioning that this talented lady has embarked on her academic journey as one of my Ph.D. students.

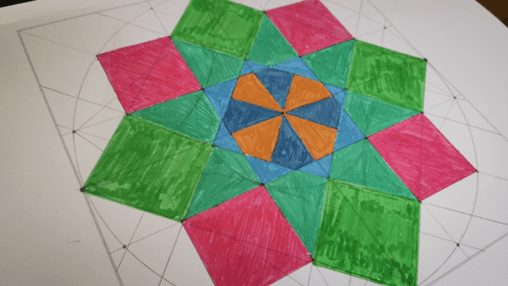

In the third workshop, designed for older children, the focus shifted to the intricacies of arabesque design. Beginning with a basic shape, such as a circle, it evolves through precise geometric progressions, culminating in a complex yet aesthetically pleasing pattern. Formulating these instructions, my mind was transported back to my freshwoman year as an architecture student in Syria, where we frequently sketched these intricate designs. (see Figure 4). After the workshop, a parent’s gratitude resonated deeply with me. They expressed, “Thank you for introducing our children to these traditions in such an accessible way. You’ve kindled a desire within us to explore our rich Syrian heritage when sharing with our kids, while also reminiscing about the high standard of education we were privileged to receive back in Syria.”

Figure 4.

Work by one of the children who participated in the Arabesque workshop.

As the constraints of Covid-19 began to relax, I found myself graciously invited to two Iftar events during Ramadan. The first was at a family residence, while the second was a special gathering of female teachers from the Arabic school. It had been five years, but in those moments, it felt as if I had been transported back to Syria. It wasn’t just the familiar aromas, the authentic dishes, or the comforting ambiance, but also the warmth of the hospitality. Their inclusiveness, embracing me as a Christian, evoked memories and feelings of home that I had long missed.

‘Their concerns resonated deeply within me, accentuating an urgent call to action.

From the narratives shared above, it is evident how deeply immersed I have been and continue to be in this experience. Navigating the overlapping identities of a Syrian, a single mother, a Christian, and a researcher has been a profound challenge. The boundaries between my personal and research identities are often porous, if not nonexistent. Yet, my driving force remains my dedication to amplifying the voices of my community, ensuring they resonate in places and platforms where they might otherwise remain unheard. It isn’t just about narrating their stories; it’s about extracting lessons from them, showcasing their indomitable spirit, and highlighting the resilience they embody. I passionately seek to reshape perceptions, emphasizing the educational prowess and tenacity inherent in the Syrian identity.

Simultaneously, my commitment extends to the academic realm, specifically to my academic haven, the University of Liverpool. I’ve tirelessly grappled with the delicate balance of ethics, striving to maintain an objective stance when reporting to the scholarly community. There was a moment when I attempted to interweave my autoethnographic tales within a formal academic paper. Alas, the rigidity of academic structures sought a more straightforward narrative. Hence, I am genuinely appreciative of this platform, which provides me the freedom to voice the profound emotions and insights within. Perhaps, when a reader engages with both narratives – the personal and the academic – they might discern the harmony within this juxtaposition. While I hope I’ve been successful in conveying my story, penning this piece has undoubtedly been cathartic for me. It’s not just an account; it’s a piece of my soul, and I’ve relished every moment of crafting it.

References

Ellis, Carolyn; Adams, Tony E. & Bochner, Arthur P. (2010). Autoethnography: An Overview [40 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Art. 10, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108.

Angelou, Maya. (1984). I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. London: Virago Press, pp. 8.

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. (2023, August). What is Intangible Cultural Heritage? https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003.

Credits

Featured image and other images provided by the author

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition