Shifting Gently from a Well-lived Life: A Beautiful Living and Passing

Author’s Memo

This autoethnographic article tells the story of the death of the my dad in 2011. It attempts to answer the phenomenological question, “Can dying be done well?” It recounts vignettes of the my father’s life, his final week, and the deep bond he shared with family and friends and the ease with which he let go of this life. The invaluable role of palliative care nurses in the final days of one’s life is captured with poignancy and grace. Among other things, it is a story of gently letting go, family connections, growing up in Fiji, and the symmetry of birth and death.

I was born and raised in Melbourne, Australia. I spent my childhood roaming my father’s four-acre property that neighbored the Dandenong Ranges National Park. We holidayed in Fiji, where my father was born and raised. As I sat by his deathbed, by the window framing his garden and singing the songs of Fiji, he left us. The journey felt strangely familiar, it reminded me of the birth of my son. Letting go, holding on, love. It’s all intertwined; I can barely theme the data.

It attempts to answer the phenomenological question, “Can dying be done well?”

It has been over a decade since my father died and it’s only now that I can bring some sense of order to the largeness of the emotions. By thinking qualitatively, intertwining cognitive and emotional processing it is possible to explore themes and articulate complex ideas in simple and elegant language (Saldana, 2018). I am a bystander now, watching the friends of my parents leave; my teachers; leaving this life and I am overwhelmed by an emotional awareness. Unlike most others, my dad died so well.

He died quickly, painlessly, at home, with his family, in the evening, in the winter. The palliative care nurse told us at the time not many people let go of life this easily. Most hold on; whether it be unresolved issues, a lack of peaceful acceptance of the end, fear, uncertainty. Most hold on longer. What a gift my father gave us with his gentle, easy going.

It recounts vignettes of the my father’s life, his final week, and the deep bond he shared with family and friends and the ease with which he let go of this life.

The living

If my Dad could have written a script for his life it would have played out exactly as it did. An adventurous childhood on a remote and volcanic coconut plantation in Fiji, a formal education that allowed him to pursue his interests in horticulture, a patch of mountain land, a blank canvas for his dream garden. Opportunities to travel all over this vast and amazing planet, from end to end and with considered detail. A love of food, wine, nature, God. A partnership with a woman who supported his dreams while still living her own. A deep love for his children and his children’s children and the chance to see them play and grow; to share a love that knew no bounds. A circle of love as he shifted gently from a full and well-lived life.

If it is possible to die well, Dad showed us how. It is only now, a decade later, that I can reflect on the strange beauty of his gentle shift.

It has been over a decade since my dad died and it’s only now that I can bring some sense of order to the largeness of the emotions.

The knowing

Wednesday 11 May, 2011.

I sat with my beloved Dad, between my sister and my mum in the consulting rooms of a private oncologist.

We had known for one short week that Dad’s bones were riddled with cancer. We were told on this day his liver also.

The primary cancer: unknown

The prognosis: weeks

A liver biopsy was recommended – then we would know the primary source, but knowing would not change the outcome. My darling dad was dying. We refused the biopsy, not seeing the point of a painful, intrusive medical intervention. Dad wanted to die at home. We set out to make the journey possible.

Dad slumped down in the car. My mum, sister and I embraced, weeping as the rain fell steadily. We pulled ourselves together. We had a job to do.

My usually emotional dad said calmly

“I’m dying. I might only live a week.”

A circle of love as my dad shifted gently from a full and well-lived life.

The journey

He embraced his new project with his trademark diligence and grace. In a strangely primal way he made the act of dying his final well-planned journey. We sat by the fire and ate a pie from the local bakery. He called it a “dog’s eye” and sipped his takeaway cappuccino. As I collected the next round of fire wood my sister-in-law arrived with dinner and a heavy heart. We sobbed and hugged in the rain by the wood pile. My 4 year old nephew charged into the house with his usual childlike enthusiasm. He threw himself onto Poppa’s knee, uninhibited by the heavy grief pulling on the rest of us.

“Poppa, I kicked two goals at soccer.”

Poppa smiled.

My brother drove directly from a work commitment in country Victoria. All the way he vowed not to cry. When he arrived the sobbing began.

If it is possible to die well, Dad showed us how. It is only now, a decade later, that I can reflect on the strange beauty of his gentle shift.

The week

The days in the week that followed brought with them a stream of visitors. The rich threads of Dad’s life knitting his final farewell garment. My Dad who never felt comfortable being seen in his pajamas, never dressed again.

On Thursday

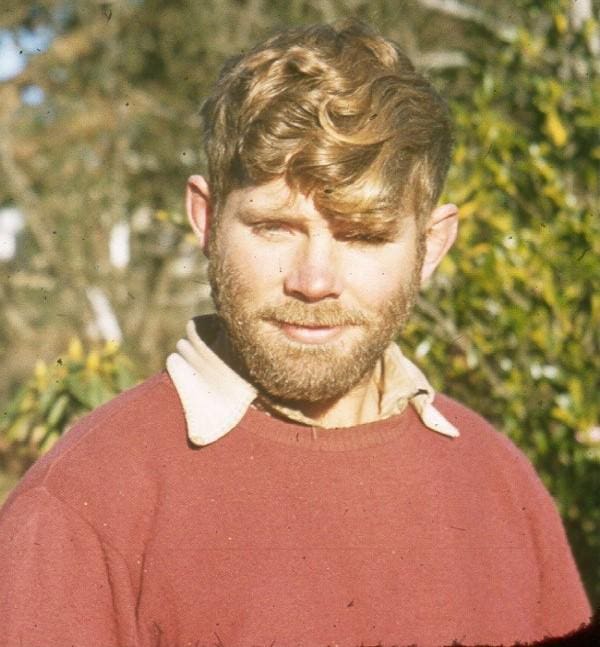

Dad’s sister arrived from Adelaide with her husband. They sat by the fire and looked at photos of their early years growing up in Fiji. The crystal clear waters, the wispy white sands. Dad, not so long ago, young and strong, his feet wrapped around the trunk of the palm tree, his feet knew what to do to take him to the top. My childhood eyes watched in wonder.

My Auntie said goodbye to her brother.

On Friday

The angel appeared. The palliative care nurse with shoulders broad enough for us all to lean on. She spoke positively about medications and plans to facilitate dying at home. She cleared the path, for what to us, felt like impossible terrain.

Mum and Dad’s travel companions of 20 years arrived. They had traveled all over the world together, Iceland, Norway, Morocco, Israel, Peru – but never a journey like this. Their visit was punctuated by shock, disbelief, and tears. Dad had methodically planned their next trip, they were due to leave in 8 weeks. Dad told them they would have to do the trip together in their dreams. They told him they loved him and thanked him for everything. Dad held up his arms and thanked them for coming.

They said goodbye to their travel buddy.

On Saturday

Dad’s dear church friends arrived. Mum met them outside – a repeat of the sobbing embrace by the wood pile.

“He’s my friend.”

“ I need him for another 15 years”.

“We can’t let him go.”

Prayers ensued. Pleading with God. We are not ready. Please God don’t let him die. Dad stoically chose the hymns for his funeral and left them safely in the hands of his friend, the church pianist.

More goodbyes.

In the afternoon Dad commissioned mum to go to his regular butcher and get the weekly meat for the traditional Sunday roast.

On Sunday

My sister and I spent a quiet morning with Dad. He was a little agitated. He couldn’t locate a loose leaf tea that had been dropped over by a friend. The tea allegedly “cured terminal cancer”. He was breathless and tired, but he sat with us by the ever-burning fire. We talked about Cradle Mountain, Gallipoli, and The Royal Wedding. The sitting didn’t last long. Dad resorted to his bed. His lips were dry. We lovingly administered paw paw cream.

“Neuquen, Neuquen” Dad muttered.

We weren’t sure at the time what he was saying but we do now. His dry lips had reminded him of Neuquen, an arid province in Patagonia.

It was Dad who usually prepared the hearty Sunday lunch. He had done so the week before. Luckily he had passed on this legacy. We all knew the right cuts of meat, the right temperature, the right amount of time to cook and let it rest. My husband had learnt well. He had cooked with Dad countless times. On this day he prepared the meat perfectly while the unthinkable unfolded in the bedroom. We huddled around Dad’s bed, our plates perched on our laps, the grandchildren on a little table at the end of the bed. Dad sent my brother down to the cellar to fetch a 1972 Shiraz he had saved for a special occasion. It was corked. But we sipped it anyway. It didn’t matter anymore.

Among other things, it is a story of gently letting go, family connections, growing up in Fiji, and the symmetry of birth and death.

“Cheers”.

The chink of the glasses sounded the same but the mood was hardly cheery. It was my sister’s birthday, but none of us were celebrating. After lunch Dad noted the moving figures of his grandchildren running in the garden outside his bedroom window. This was what made his heart sing. He had spent nearly 50 years creating this four acre garden wonderland and the laughter of the children running on the lawn was their greatest parting gift.

At 5:30pm, Dad roused from his sleep and asked “What’s for dinner?”

“You want to get up Dad?”

He did. I carefully placed on his slippers and dressing gown. When I left him that night he was sitting up at the dining room table wearing his reading glasses, novel in hand and preparing to eat some dinner.

“Bye sweetie girl” he said when I left. A small glimmer of hope filled my heart. My Dad was still very much alive. I returned home and held my children tighter.

On Monday

My Dad’s brother and his wife arrived. My cousin from Brisbane. They sat by his bed for hours. My cousin cried.

My Uncle said a prayer. He said good bye to his brother.

The angel again, she couldn’t give a time frame. She didn’t know.

Dad slept.

Exhausted, my mum and sister sat at the dining room table arranging the hire of a hospital bed and trying to make sense of the ever-growing list of medications. It was the first time the house had been so empty in days. The silence was broken by a loud crash and some frantic swearing. Dad, forgetting (or ignoring) how ill he was and wanting to be independent had fallen in the bathroom, his head split open. The bleeding could not be stopped. “You’re naughty,” my sister told him. The twinkle in his eye we knew so well. Yes, he knew he was naughty.

He asked for my brother. My brother came. The paramedics arrived, they couldn’t stitch, but they could take him to the hospital. NO! Dad wanted to die at home and we weren’t letting him go now. Mum held towels against the blood filled bandage and waited for the locum to arrive. She sat in bed with him, maintaining pressure where the stitches were and holding her man. Sleep was unlikely anyway.

On Tuesday

The phone rang at 6am. It was Louisiana, Dad’s dear friend from Chile. He had met her on his work trips through the apple orchards of South America. He had supported her through the loss of her mother. She wanted to tell him she loved him.

“I am terminally ill, you are my best friend in Chile, I am too weak to speak.”

The sobbing had now spread to the other side of the world, it could be heard through the muffled phone line.

The hospital bed was delivered and perched beside the large bedroom window so dad could see the lawns, the mountain, the autumn leaves. And then came the stream of grandchildren with their pictures and songs and broken hearts, beside the hospital bed, beside their bandaged Poppa. Kisses and Love, Kisses and Love.

Dad could no longer swallow. The tablets would not go down. He didn’t want food. His mood shifted ever so slightly.

“You’re killing me with all these drugs.”

A strange surge of guilt.

Were we?

He slept.

We sat by the fire, Mum and I.

On Wednesday

Mum and I had breakfast by his bed. He held a piece of toast momentarily in his hand but didn’t eat it. He asked for Milo and sipped a few small sips. We tried to give him tablets, crushed this time – he accused us of rushing him. His body was slowing down and we were not synchronizing. We gave up on the tablets. What was the point now?

The angel flew in. Our strength. She sat Dad up and sponged him down. An image I’d like to erase. The frail, withered body of my dying dad, so exhausted, so depleted. His distant eyes glazed over.

“You’re doing so well” she said. “Nearly there”.

For a moment her face switched, and I could see the midwife, delivering my son.

“You’re doing so well… nearly there.”

Maybe 48 hours…maybe.

She inserted a butterfly in his leg. Morphine and anti nausea was all he needed now.

I held his hand, I moistened his lips and I massaged his swollen ankles. He was lucid. That never changed.

“Gardens and sun and all things good.”

“Peacefulness.”

“I’m doing well sweetheart, don’t worry about me”

I worried.

The GP arrived to check the stitches. It seemed ridiculous now. He asked when she was coming again.

The angel flew in. Our strength. She sat Dad up and sponged him down. An image I’d like to erase. The frail, withered body of my dying dad, so exhausted, so depleted. His distant eyes glazed over.

‘Whenever you need me”…he wouldn’t be needing her.

He mumbled about “the lack of architectural symmetry” of a friend’s split level home in Hobart. He liked things a certain way: he never would have died in Spring – it would have been the wrong time in the cycle. Spring was blooming, beginnings. Right now the garden was entering winter dormancy. The days were shortening, the trees were nearly bare.

Late in the afternoon and out of nowhere Dad said

“Wunderbar, I’m halfway there”

“Half way where?” I asked.

“Dad..half way where?”

Dad slept.

I sang many songs to him, but the one that resonated the most was ISA LEI, the Fijian sad farewell song. Somehow it was there inside me, waiting for this time. Dad had grown up in Fiji. He spoke fluent Fijian. His beloved Fiji.

Isa Lei, na noqu rarawa, Niko sana, vodo e na mataka.

I didn’t know the translation and I doubt my pronunciation was right – but Dad would have known.

Isa Lei, the purple shadow falling, sad the morrow will dawn upon my sorrow, forget not when you’re far away. I wasn’t sure he was conscious. But he was. When I stopped he firmly squeezed my hand. I quietly sang it again.

The letting go

By early evening Dad’s three children had gathered by his bedside. His breathing had changed. He had a thready pulse, was peaceful. and calm.

“We are all here Dad”

We mentioned our names one by one.

The names he’d loved and chosen.

He roused. His head turned.

“Where are we?”

“We’re at Sherbrooke. See the mist on the mountains. The rain has stopped”

He turned his head and gazed longingly at his mountain vista.

“What time is it?”

“It’s 5:30 Dad”

“morning or evening?”

“Evening”

…was peaceful and calm.

He closed his eyes and slept by the window, well-lit by the bulging full moon, smugly unphased.

He would have planned to die in the evening. Evenings like winter were all about endings.

Mum joined us, huddled around his bed. We talked and drank wine. What else could we do? We waited. He slept. The rhythm slowed. It shifted ever so slightly. His eyes opened, heavy glazed over eyes, less than half a soul inside. A final breath. One more. The body was still. His hands were still, his hands that held our hands and held our children’s hands. Dad’s strong weather worn hands.

We hugged. We sobbed. Mum’s husband was gone. Our Dad was gone. Poppa was gone.

My sister-in-law returned with my 3 year old daughter.

There was an intense stillness. The room was heavy with tears and sadness.

“My darling girl – Poppa has died’

She sensed the mood and in her tiny voice she asked

“But how can he be dead if he’s still in his bed?”

I did not have an answer.

The nurse told us, my dad did a good job of dying. She said some people hold on and some are ready to go easily. I hoped that it was love that carried him with ease.

We sat by the fire. It had burned all week, warming the stream of visitors. Dad’s companions on his final well planned journey. He had said he might only live a week, and that is exactly what he did.

He would have liked the symmetry.

References

Saldana, J. (2018). Researcher, analyze thyself. Qualitative Report, 23(9), 2036–2046.

Credits

A vista of her dad’s garden by Tania Hume

Dad as a young man in the garden by Tania Hume

Featured image of a peony rose in full bloom in the garden by Tania Hume

A man in Yasawa Island, Fiji, by Nicolas Weldingh for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Tania Hume was born and raised in Victoria, Australia. She grew up on a four acre property complete with a large strawberry patch and a series of sloped lawns adjacent to the Dandenong Ranges National Park. With qualifications in Education and Psychology she loves crafting and analysing personal narratives in an attempt to explain and understand social phenomena. She currently works in Special Education and lives in Melbourne with her husband, two teenagers, dear, old golden labrador and a sassy black schnoodle.