Poetry Helped Me Reclaim My History: Poems of/from Photos

Author’s Memo

Some time ago I heard a friend, poet, Cecilia Wolloch read; she said (I am paraphrasing) “I am going to read a poem written about a place. I was distracted and didn’t think I noticed anything. It seemed as if I wasn’t really there.”When writing the poem, she continued, “I realized to my surprise I recalled many intricate details.” Well, I could say the same thing regarding a decade of my life.

This decade is the culture-rich and revolutionary one of the sixties. Autoethnography comes into play as my experience or might I say re-experience of the sixties took off from the remarkable photos in “Anarchy, Protest & Rebellion,” assembled by Fred W. McDarrah. What started as an aesthetic and enjoyable examination of historic photos became the subjective ride into the world of these images. These poems are an excursion into the personal, cultural and political climate of the 1960’s prompted by these rich depictions.

The start was the image which was iconic in itself. The photos were from the Village Voice and conveyed the counterculture of the 1960″s. I entered the photo from a “neutral” point of view, sometimes participating in the action of the scene and at other times consumed in a memory, feeling or event guided by (to different degrees) the image. The image could be of a person, event or a place or all the above.

“Autoethnography comes into play as my experience or might I say re-experience of the sixties took off from the remarkable photos in “Anarchy, Protest & Rebellion,” assembled by Fred W. McDarrah.

More often than not I was familiar with the location, the event or the people depicted, but like Cecilia I didn’t think I was fully present. I crossed paths with many of the people in the photos. I was at several of the demonstrations chronicled in the book. There are photos of the “Bread and Puppet Theatre,” a group born out of the protests to the Vietnam War. I performed with them at the Fillmore East. There are photos of The Living Theatre. I saw all their productions and met a few of the members. One member became a close friend. There is a photo of Tennessee Williams. I had the good fortune to meet him when I was performing on Broadway. There is a photo of Abbie Hoffman. I played him in a play and we later became friends.

There is a photo taken at the “Church Disco.” My girlfriend actually did work in the coatroom. In “Hollows,” I was very aware of this scandal and horrible conditions at Willowbrook caught in this photo; I had been working with autistic children at the time. (mot included in this group of poems) I was at the Worlds’s Fair in Queens referred to in “Subterranean,” Well on and on my connections became apparent and looking at the photos ignited the realization: I played a part in the cultural and political tapestry of that time. I was not a lead player but I participated. The fusion, of both objective investigation and personal exploration was evident.

“Seeing these photos and writing these poems helped me to own my experience.

From Stonewall Inn to Al Pacino in his first play, to Woodstock, to the Be In’s in Central Park, to cuisine on the lower east side. to Muhammad Ali and the protests to the Vietnam War, these photos explore them all with the backdrop and the sometimes, lead player, “New York City.” In essence I felt alienated during that period in my life. I might have been confused or emotionally distant but I did take note of what was around me. Seeing these photos and writing these poems helped me to own my experience. We have all heard people say “poetry saved my life.” In this case it helped me reclaim my history. I believe the dynamic taking place was autoethnography, a hybrid of my investigation of the 1960’s coupled with my personal experience.

These are poems in response to photos in “Anarchy, Protest & Rebellion,” assembled by Fred W. Mc Darrah.

Photo, p. 217

Unisphere sculpture by Gilmore D. Clarke was

The centerpiece of the New York World’s Fair, 1964-65

SUBTERRANEAN

The pavilions, rides and global

contributions attracted

little of my attention

and I am sorry to say

nor did man’s flight to the moon.

The concoction of this World’s Fair

where the Unisphere rules—

and still does—

in Flushing Meadows, Queens

where for a few months

countries got along,

borders porous;

water fountains lit

in the background,

with elevated towers

lifting Robert Moses and crowds

to heights

left me in a crawl.

Tangled, earthbound,

with a singular periscope,

I tracked nothing

but myself.

This photo cuts

off the sign,

“Carribean Pavilion.”

We puzzle over ribbean avilion.

Names, severed.

Meaning lost.

I rarely wandered

above 14th street.

Photo, p. 252

Sal Mineo at a play rehearsal, August 21, 1969.

AS IF

Sal Mineo with a cigarette hanging

from his mouth, in an unbuttoned

denim shirt— yes, the boy who died

in James Dean’s arms,

the boy who followed

him and Natalie Wood around,

who stood for every kid

who longed for cool parents.

Sal said, “Hi, Paul.” Sal Mineo, said, “Hi Paul.”

“Hi Paul” shot out of celluloid,

as if we were both in Rebel Without a Cause.

Sal, backstage, said, “Hi,

Paul,”

as if we were friends as

I left my dressing room

and although

he was killed in the film, he seemed

to be resurrected to greet me.

Soon the police would arrive

at the Morosco Theatre

on 45th Street just west of Broadway.

Surely they would shoot my brother Sal

again and then hopefully shoot me.

Photo, p. 108

Curator Frank O’Hara in the Museum

of Modern Art garden, January 20,1960,

with Auguste Rodin’s “St. John the Baptist, Preaching”

FIFTY-THIRD BETWEEN

FIFTH AND MADISON

There’s Frank O’Hara in the same

posture as the sculpture,

hands, legs and fingers in perfect sync,

as spontaneous

as his verse.

I remember this spot

in the Museum

when entry was free

and I would bite

into an apple

from a bowl

of Cezanne’s fruit arrangement,

stain my lips with color,

murder an innocent

with Bruegel,

ogle women

from multiple angles

with Picasso,

soar in oil and clouds,

as familiar

as the crannies

of an alley

where I played Ring-a-levio

as a boy

when my breath

was short

from excitement:

the make-believe

that seemed

so real.

I’d go down

into the museum basement

for a Louis Malle film

or Goddard:

steal a car

with Jean Paul Belmondo,

preserve the severed hand

in a jar of formaldehyde

— of a dear, dead friend—

set it on the shelf

next to a few oblivious books

in what’s the name of that Max Ophuls film?

No it wasn’t Ophuls.

Give me a minute…

…Jean Vigo, L’Atalante.

Photo, p. 100

A crown of daisies, Central Park,

April 14, 1968

EAST VERSUS WEST

At the BE-IN of beads

and acid. We are all one.

It was confusing

with the rage

of so many years

beginning to surface

while love climbed the bark

of every trunk

and me dissolving into atoms.

The lamppost as holy

as a maple tree

with ancient Indian patterns

talking about un-self, no borders,

and chit-chat about surrender.

Everything stripped

from the word assigned to it.

Revealed.

The terror of last night could be

overcome by smashing dishes

or seen in burgundy, blue

and violet prisms

contracting and expanding….

Photo, p. 329

In “three days of peace and music,”

Over thirty bands entertained from sunup until sundown,

August 16, 1969

IT TILTED THE ORBIT OF THIS PLANET

The tops

of heads, frame to frame,

roll and sweep along:

the festival known as Woodstock, August 1969,

as studied as the invasion of Normandy.

I’m not the mustached guy strolling towards

the lens

or the infant getting his diaper changed

or a boy in a white T-shirt

with his back to us.

No, I am outside the frame in a VW Bug

with four others, voting whether

to continue through mud

with two miles to go

to this photograph.

It’s one to one.

Lightning.

Rain.

Everything soggy.

Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Janis

share umbrellas.

The Who erupt in

a downpour.

Hendrix will destroy

his guitar. The folk singer

with the lisp is lost

in his notes, the one

who had the crush on what’s-her-name?

The tally is two to two. I break

the tie to make

the U-turn.

I didn’t know I’d

see the film.

I didn’t know

I’d see this photo.

I didn’t know.

It was 1969.

I knew everything

Photo, p. 17

The Bread & Puppet Theatre

in the first Vietnam protest,

Washington Square, March 15, 1965

The three-storied puppets,

hands bigger than heads and gowns

to the ground, a 1962 Mercury

parked to the side

with slanted front lights

watching it all.

The Bread and Puppet Theater

parades down MacDougal Street.

VIETNAM is bold and hand printed

on the chest of a puppet,

blind as the war,

and inside the puppets

are puppeteers who follow

instructions from the creator, Peter Shulman,

rather than a drill sergeant.

A musician with a papier mâché-skeleton face,

meant to spook us into

sanity, beats a marching drum.

A fire hydrant in the lower right hand

corner listens to the pleas for peace.

I want to mention what happens

under the drapes of these oversized

puppets, how we both maneuver

them and fondle one another,

stroke each other’s genitals

while we protest

while our classmates from high school

disappear.

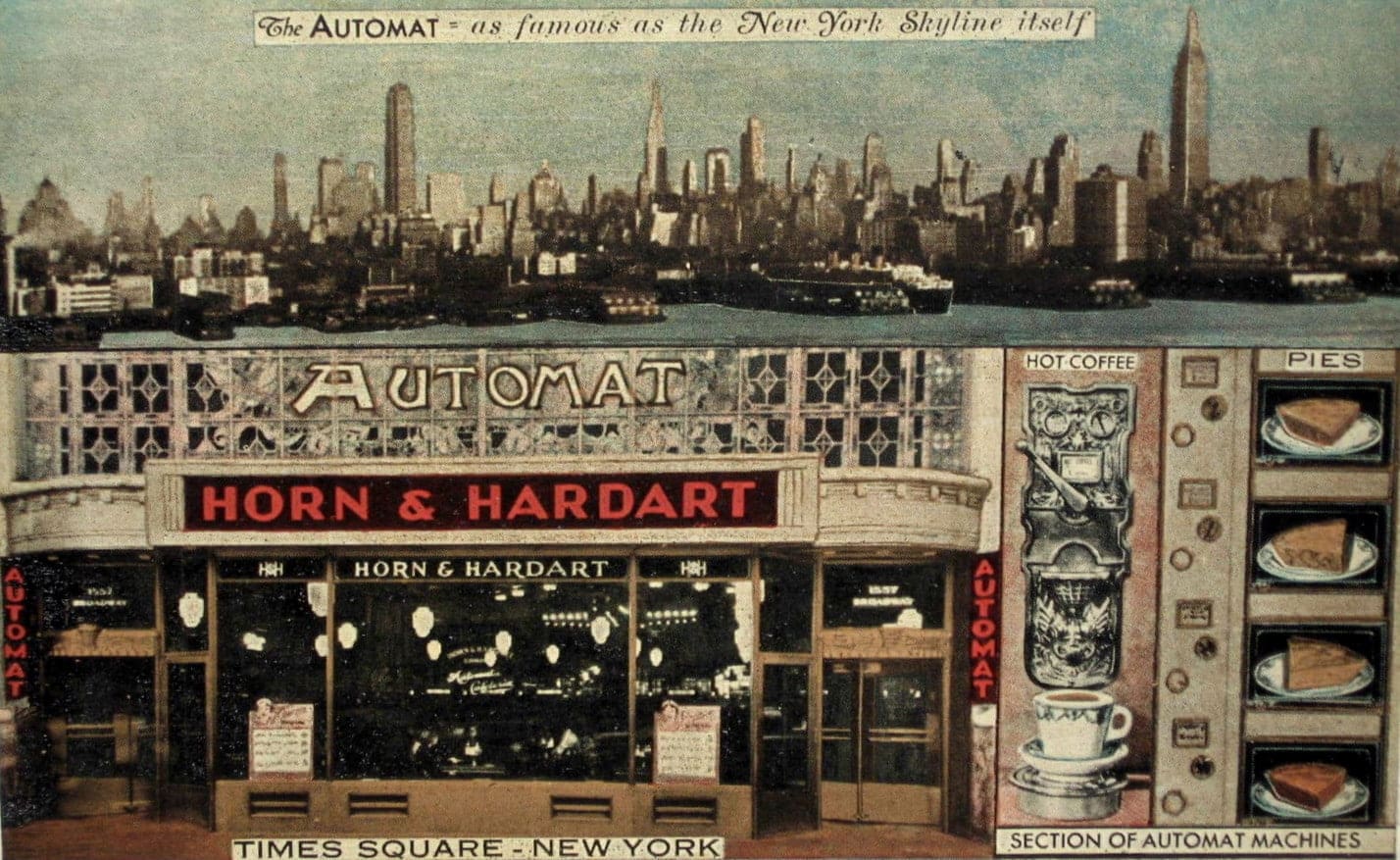

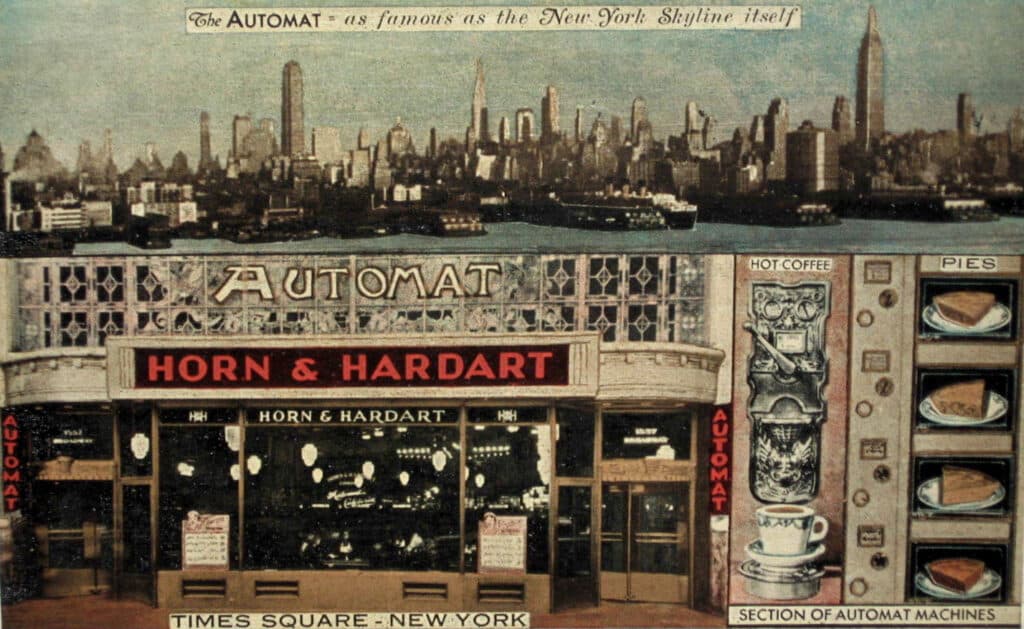

Photos, pp. 174-175

The last Horn & Hardart, West 57th St.,

June 19, 1960

GONE

I was beside myself to hand a dollar bill

at the marble booth at the center of

the cafeteria and witness the Vegas-like

agility of Mary, who shuffled coins like cards,

tossed twenty cool nickels my way.

Here are photos of the gold gargoyles,

marble, glass, and the spigot with the head of a dog,

tongue hanging. Just crank the handle

above and, for five nickels, place your cup under

for coffee, then proceed as four nickels

will open a small glass door where pies

prostitute themselves. Temptation is legal

and these cream pastries, chocolate

and lemon meringue, parade behind

the see-through windows. Take your pick

in the automat where men wear hats

and eat off trays and kids like me

were off our leashes. Baked beans,

macaroni, slot machines and swinging doors.

Touch what you like for a few easy nickels,

everything within reach as we skipped

from showcase to showcase. There’s

a grilled cheese sandwich. Dripping.

There’s Bessie putting the third nickel

in the slot, eye level with apricot pie.

She wears a wool jacket, her hands

are still chilled, but so eager.

Photo, p. 63

Hot knishes all day long at

Avenue C, November 7, 1964

BROTH

We’re on avenue C and 6th Street,

“Knishes 15 cents.” A man with a coat

to his knees grasps the handles

of his cart on a cobbled street,

gloriously irregular in its line-up of stones,

six blocks from where my grandmother

lived on 12th Street between B and C,

that tenement apartment tucked

in the 3rd floor walk-up where I’d enter

into a museum of smells

with the samovar on a top

shelf, as seductive as the casbah,

and a bathtub in the kitchen;

a bowl of chicken soup,

with an occasional eggshell

lost in broth, welcomed me.

This is the Lower East Side with fire escapes

above treetops, always above,

witnesses to the changing demographics.

Not burnt, please. Is it fresh?

Who made these? Hot but not too hot.

A kasha one, please. Yes, with mustard.

Photo, p. 90

Tim Leary sits with Allen Ginsberg and Richard Alpert

at the Fillmore East, 1966, the event was

a“psychedelic, religious celebration.”

STAGELIGHT

Tim greeted me at Millbrook,

his LSD farm in New York

and he stood like a waspy god

in sandals, as friendly as a senator

and he had my teenage vote.

At the Fillmore I watched him

describe playing baseball, how acid

slowed the pitch and in the stitching

of the ball he found the history

of the game, contemplated the peace

it embodied, the angles it celebrated

and he had time to reflect

on the Big Bang as he swung his bat

with perfect timing and swung his bat

in harmony with the rotation

of the planet and with his swing

creation was explained and so much more…

Mic in hand, legs nearly crossing,

Allen Ginsberg to his left,

while bombs dropped

on Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam

and darkness

in this photo except for them.

Photo, p. 1

Heavyweight Champion Muhammad Ali

in basement of Madison Square Garden,

March 16, 1967

ROPE-A-DOPE

Ali in a robe, leaning

on the ropes, fatigued,

the year he refused induction,

his mouth closed.

My father would love

his closed mouth

free from braggadocio

and rhyme, as unimpressed

with Ali as he was with me.

I remember when

I said Johnson and Nixon

were the same, thinking of

the blood in Vietnam,

and my father spewed disgust.

Was it really disgust at

his father who deserted

or his mother who deserted

her sanity or me who deserted

his opinions?

I met Ali in Santa Monica when

there was peace in the east and

he was shuffling and dancing.

I leaned like him on the rope

outside the ring and he smiled

and waved me in.

I said I like it outside

then climbed over the rope.

Ali circled. I didn’t think he even

noticed my presence.

He flicked a jab and followed

it with a light hook and a cross;

I did the rope-a-dope and he

recited: you’re a good learner friend,

but you will be out in the end

and that’s all I remember.

Credits

Featured Image of Horn&Hardart Times Square New York circa 1939, public domain from Wikipedia

Photo of the Unisphere sculpture close-up in New York by Reno Laithienne for Unsplash

Photo of Auguste Rodin’s “St. John the Baptist, Preaching” in Italy by Max Avans for Pexels

Image of Horn&Hardart Times Square New York circa 1939, public domain from Wikipedia

Image of Mohammad Ali by Nelson Ndongala for Unsplash.

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

“Interrupted by the Sea,” Paul’s second collection of poetry was published by What Books Press. First collection: "Chemical Tendencies,"(Tebot Bach). Paul produced “Why Poetry” on Pacifica radio in L.A. . He taught Poetry at L. M. U. and Beyond Baroque. Paul works as an actor.