I am the Roe Generation. Our struggle is now.

Author’s Memo

The 2022 U.S. Supreme Court Dobbs v. Jackson decision gives rise to reflection on my personal experience as a member of what I call the “Roe Generation”—the cohort of those of us whose reproductive years were contained entirely within the half-century between the 1973 decision, Roe v. Wade, and its undoing. I contemplate the implications of Dobbs for younger women like my daughter living in a post-Roe world by contrasting my own ability to exercise freedom of choice regarding whether to become a mother with the struggles endured by my mother and grandmother in a pre-Roe world.

“Here I share my personal history lending emotive understanding to our collective experience of our present moment.

As a professional historian, my goal in this essay departs from the usual objective history I write. Here I share my personal history lending emotive understanding to our collective experience of our present moment. My goal is to inspire readers to take action in the hope we can move towards a better shared future where the freedom to protect oneself from or end a pregnancy is always and everywhere considered to be a permanent and inalienable right.

I am the Roe Generation. Our struggle is now.

The U.S. Supreme Court legalized birth control for married people in Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965, and for unmarried people in another landmark decision, Eisentstadt v. Baird, in 1972. Soon after that, on January 22, 1973, it announced its most pivotal decision of all—that abortion was a matter of privacy rights enshrined in the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in the case of Roe v. Wade. That summer I turned 10 years old.

By the time of my menarche two years later, enough birth-control and abortion provider services, including Planned Parenthood—the only one I was ever aware of—had established clinics in a nearby larger town, accessible to me and my girlfriends by bus. I never needed to get an abortion, in part because no one raped or coerced or talked me into sex before I wanted sex myself when I was seventeen and fell in love with the most unlikely and unprepossessing young man in my orbit. And, because Planned Parenthood helped me access birth control pills at an affordable price for a teenager working after-school for minimum wage. And, because, by then, I understood the stakes, having been the confidante of enough friends who had not gotten on the Pill before beginning their sexual lives and had gotten pregnant, whom I had sometimes accompanied to get their abortions.

“The decision to remain pregnant should be as much in a pregnant person’s own control as whether to have sex in the first place.”

I knew the Pill was an absolute imperative for me. I did not choose to rely on condoms—also accessible to me and to my boyfriend—not because he was unwilling but because I had heard stories of condoms breaking and passionate foreplay getting out of hand before they unwrap it. And, even more because I felt vulnerable to rape pretty much every time I was out and alone at night. I knew rape would be hard enough to bear up under emotionally and worried that pregnancy as a result of rape might just break me. I had Big Plans and had determination to go to college, no matter what it cost and no matter the mysterious-to-me logistics involved.

The only thing I knew of that could have derailed me in my determination to be an educated person was getting pregnant—as my mother often pointed out to me. I took her warnings to heart and made sure an unwanted pregnancy—my mother’s fate fourfold—was not going to be my fate.

In the first instance—college—I was right, and my determination and determinedly unpregnant status got me through an undergraduate degree, a master’s degree, and all the way through a PhD degree even.

In the latter instance, I was wrong.

“But June 24, 2022 and the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson decision was still a dozen years away. I still had the right to an abortion.

I did get unintentionally pregnant—thirty years later, after three full decades of steadfast adherence to rigorous and consistent birth-control use. My long-term partner of 25 years (not the same unprepossessing young man of my teenage years, thank goodness) and I relied solely on condoms after I decided the Pill added to my risk factors for breast-cancer. Regardless of the form birth-control might take, we both stayed adamantly committed to avoiding parenthood. From the start of our relationship, he had made it clear that he was no less appalled at the thought of inadvertently instigating a pregnancy in another person as I was feeling panic at the prospect that I might inadvertently mingle my genetic material with his inside of me and end up incubating an embryo long enough to produce another whole human being nine months later.

Yet, however unwavering in that regard we both were, as well as steeped in the wisdom of our middle-aged years, we did at age 46 and 50 what I swore I would not do at the tender age of 17—let passion and foolish optimism get past my determination to protect myself from pregnancy.

We were deep in a magical wood that skirted a salt-sea cove off the coast of Maine. We had trekked a third of a mile through the pines, footsteps crackling on frosted ground, to a tiny sleeping cabin with just extra socks, a thick blanket, and a thermos of soup with us to keep us warm. Both of us only realized we had left our condoms back in another state once we settled under the blanket for the night.

“I am the “Roe Generation.

We contemplated the chances we were taking. Surely, we were both too old for worrying about one random act of unprotected sex? For years we had been hearing tales of women many years younger than me who were desperate to get pregnant and bankrupting themselves on in-vitro strategies. So many dire stories about the difficulties encountered getting pregnant after 35 that we thought the statistical possibility of me experiencing a first pregnancy in the second half of my 40s after one unprotected act of sex was entirely far-fetched. We decided to let loose our desperate fears about pregnancy and indulge in the only unprotected sex of my lifetime.

A few weeks later, when I realized I had missed my period, I was pretty sure I was experiencing the start of menopause. But, recalling our recent unprotected tryst, I took a pregnancy test just to eliminate the—exceedingly ridiculous we thought—possibility I was pregnant. And found out I was nowhere near menopause.

I was pregnant.

But June 24, 2022 and the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson decision was still a dozen years away. I still had the right to an abortion.

“The Roe decision asserted that the state did not have a claim on a pregnant person’s body; instead, the state had to to protect a person’s inalienable right to decide the use of one’s own body, whether within or outside the bounds of pregnancy.

I was less than one-month pregnant when I found out, had the money, the transportation, and the access to safe, legal, and reliable doctors who could perform it and had the support of my partner, whatever I decided. But, he was not in the decision-making position. I was. I would decide for myself what was the right thing to do. Did I want to be a mother? Did I want to spend my remaining lifetime on this earth as a parent? My male partner’s feelings about the matter were of prime consideration for me, but in the end it was my decision, and I took my time to think through that decision very, very carefully. And then I made it.

My daughter was born in 2010 on my 47th birthday.

This past year, my menses finally came to an end and my daughter experienced the onset of hers. While my menstruating years fall entirely within the half-century stretch between 1972 and 2022 governed by the Roe decision, my daughter does not share the fortunate timing of my generation—the only generation in world history whose choice to avoid pregnancy or to determine the outcome of an unintended pregnancy was, for the entire span of her reproductive life, deemed by her government to be her inalienable right.

“The decisions the U.S. Supreme Court made over half-century ago—Griswold, Eisentstadt, Roe—protected me my whole life.

I am the “Roe Generation.”

I was covered from menarche to menopause by the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment as interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court asserting that the decision to remain pregnant should be as much in a pregnant person’s own control as whether to have sex in the first place.

That sex itself is a private matter not subject to state interference unless exploitation, coercion, or intimidation was involved, and then only to discipline the perpetrator.

That pregnancy is not some sort of obligatory outcome or deserved punishment for having sex, therefore it is not pertinent whether a pregnancy is a result of rape, incest, or a passion freely engaged in.

That the unanswerable question of whether “life begins at conception” or whether the fetus qualifies as a “person,” is irrelevant to the question of whether a pregnant person legally has to incubate that “life,” “person,” “pre-person,” “embryo,” “fetus,” or “baby.”

That neither a male partner nor men as a group, not the family or the parents of the pregnant person—not even the state itself—has a constitutional right to demand the use of one person’s body for the incubation of another.

And that, even if some people feel a moral or religious imperative is at issue, their religious dogma, logic, and conclusions do not govern civil life in the United States of America.

“And, I feel especially fortunate that, as a member of the Roe Generation, I never had to face what multiple unwanted pregnancies might have done to my own health and life path.

The Roe decision asserted that the state did not have a claim on a pregnant person’s body; instead, the state had to to protect a person’s inalienable right to decide the use of one’s own body, whether within or outside the bounds of pregnancy. The decisions the U.S. Supreme Court made over half-century ago—Griswold, Eisentstadt, Roe—protected me my whole life. They meant I knew about and could access tools to prevent pregnancy, or failing in that intention, I could end a pregnancy if one had been imposed on me, had been accidentally triggered, or I had planned but endangered my health, my well-being, or my future…as I determined. And it meant that, when faced with an unlooked-for and unintended pregnancy, I could choose to become a mother too.

Because of Roe, my daughter can be supremely confident that the most momentous decision of my life—to become her mother—was the result of my choice, freely made.

Unlike me. I and my three siblings were like most of the kids in our neighborhood born in the pre-Griswold/Eisentstadt/Roe era. We all could count the number of months between our oldest siblings’ birthdays and our parents’ wedding anniversaries and notice that the number, without exception, was always less than nine. We grew up knowing we were no one’s choice and certainly not the product of clear-eyed, deliberate decision-making. By 1959 when my mother was 19, she and my father apparently got carried away by passion and then “had” to get married. By then, scientists had developed the Pill and it was available—to some women, but not our working-class mothers living in a little Catholic town, and not even after marriage.

“I won’t take the Dobbs decision lying down.

Our town’s pharmacist did not think married women should attempt to limit the number of children God would give or their bodies would bear. Fortunately for my mother and our family as a whole, when my mother was very pregnant with her fourth child, a female pediatrician opened a practice in the next town. It was during a well-baby check on her third and youngest child—me—when the doctor casually asked my mother if she wanted to bear a child every year or so for the rest of her reproductive years as it looked like she was likely to do without any intervention. My mother told me she cried with relief when the doctor told her that this did not have to be her fate, that she had a choice, that her fourth pregnancy could be her last, that reliable birth control existed and the doctor could prescribe it.

It was July of 1965, and Griswold had just been decided on June 7, 1965, but it was that female doctor who, in the months after my younger brother was born in August, found a way to bypass the still-resistant pharmacist by having pills sent directly to my mother in an unmarked package mailed from a dispensary located in New Jersey. Because of that doctor, and the rights conferred to my mother by the U.S. Supreme Court that summer and over the next decade, my mother bore four children but she did not bear over a dozen as her own grandmother had. Like that grandmother, my mother lost all her teeth before she was 40, which the dentist attributed principally to the four pregnancies in five years she had endured that had depleted her bones and teeth of calcium.

“Because of that doctor, and the rights conferred to my mother by the U.S. Supreme Court that summer and over the next decade, my mother bore four children but she did not bear over a dozen as her own grandmother had.

I do not know what 12 or 16 or 18 pregnancies would have done to my mother’s body or mental health. I am grateful I do not know that. And, I feel especially fortunate that, as a member of the Roe Generation, I never had to face what multiple unwanted pregnancies might have done to my own health and life path. Apparently, my daughter and her generation will not be so lucky. The U.S. Supreme Court’s recent Dobbs decision has taken away her right to become a mother in America only and always as a result of her deliberate and clear-eyed choice to do so, no matter the circumstances under which she became pregnant or which state she calls home.

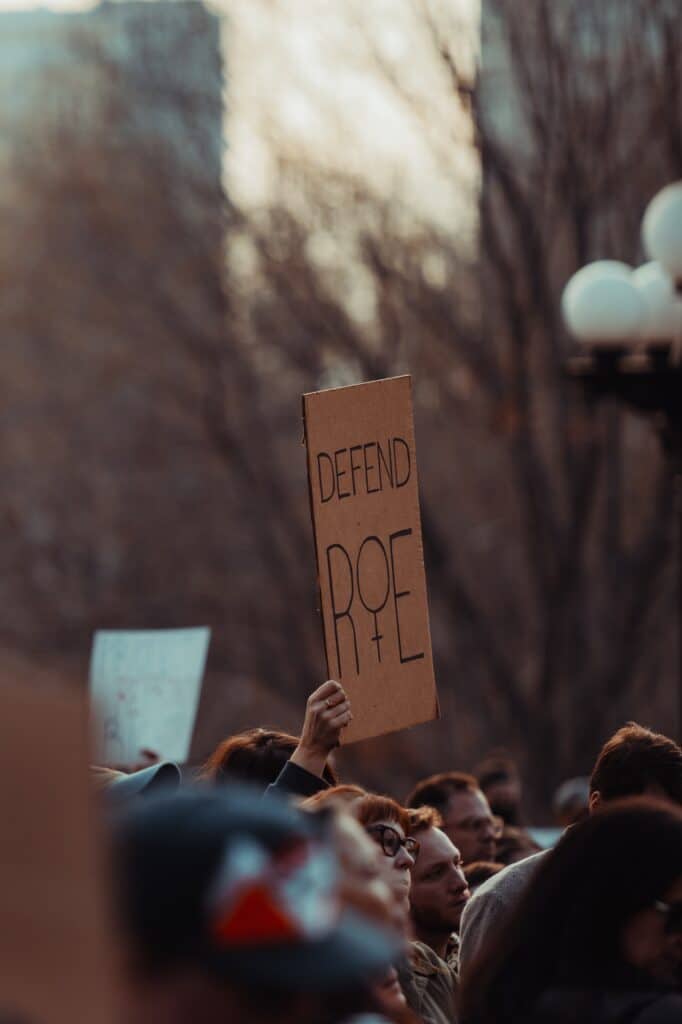

I won’t take the Dobbs decision lying down. I’ll fight against its insidious assertions that pregnancy renders a person’s body no longer their own and just a vessel for another. For that fight truly belongs to us—the members of the Roe Generation. We owe it not only to our post-Roe daughters and granddaughters but also to our pre-Roe mothers and grandmothers who endured despite the obstacles placed in their way and who fought for us so we would not face the same. They would not expect the members of the Roe Generation to give up on the gains they won. They would not expect us to be turned into cows by Dobbs or this Supreme Court.

Let us not be cowed. Let us not be…cowed.

Credits

A Photo of a poster from a protest by Colin Lloyd for Unsplash

Featured image by Zuza Gałczyńska for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Tracey Jean Boisseau is a historian, feminist scholar, and associate professor at Purdue University. She is the author of White Queen, co-editor of Gendering the Fair and Feminist Legal History, and has published many scholarly articles and book chapters on the history of American and transnational feminist identity. She is currently working on a new book, Fair Amazons: Women, Rights, and Reform at the 1853 New York World’s Fair and After, and is co-editing “Pandemonium,” a special issue of Women’s Studies Quarterly forthcoming in May 2024.