A Full-Fat Remix of Low-Fat Love Stories

Tabitha Chilton and Gioia Chilton

Low-Fat Love Stories (2017) is the result of arts-based research on romantic, familial, and intrapsychic dissatisfying relationships. It is written by Patricia Leavy, my academic mentor and colleague. And it is illustrated by Victoria Scotti, fellow art therapist, artist and collaborator. To discuss this work, I asked my daughter Tabitha, who is a writer, to collaborate with me. Mostly because she is a better writer than I am and I needed her skills. Inspired by Patricia and Victoria’s collaboration, we thought it would be interesting to work together to explore female intimate relationships. We also ended up pulling in my younger daughter Annie, as we both relied on her to help us with this project we labeled, “Full Fat Love.”

Leavy’s first arts-based research (ABR) novel, Low-Fat Love ( 2011) used fiction to manifest her research findings on how professionally successful women can “settle” for unfulfilling personal relationships. In response, many women shared their low-fat love stories (LFLS) with her. Eventually she conducted a qualitative study through e-mail interviews. Working with Victoria in an exchange of the interview texts, response art, fully developed narratives, and reimagined response art, Leavy produced a work that in seventeen stories vividly illustrates the impact of poor relationships on women’s self-worth. In these visual and text-based snapshots, we see one character after another experience self-judgment, shame, negative body image, anxiety, despair, self-effacement, and other effects of negative relationship patterns.

We come to know gender, victimhood, and agency through the ways the characters experience, create, perform, and undo their identities. Women in these stories struggle with autonomy and confidence. We watch them go through waves of insecurity, defiance, submission, and numbness. The ways in which Western culture pressures women to accept less than empowering intimate relationships are illuminated and ultimately, we get a message that to change, women must take responsibility for our relationships, and stop accepting poor imitations of authentic love.

To begin to explore these themes in LFLS, we focused on the eighth narrative in the collection, which tells the story of Sara, a young girl in a large family who idolizes her older sister, Margaret. As they get older, Sara begins to resent Margaret for prioritizing her friends and exploring her adventurous adolescent side, rather than playing dress-up with her sibling. Eventually, Sara’s view of her sister is entirely different from what it once was: the beautiful, lovable, popular role model, transformed into a selfish, privileged, arrogant stranger.

The narrative then jumps to years later, after the death of their parents. As the kids sort through their parents belongings, Margaret claims the dining room table for herself, a furnishing that Sara had always told her family she dreamt of inheriting. Sara, hurt from years of feeling unseen by her sister, takes this action as a final betrayal and decides not to speak to Margaret for the rest of their lives.

Tabitha and I decided she’d be in Patricia’s role, and write in response to this story, while I would be Victoria, and make some art which illustrated it. I also made response art to several of Victoria’s original portraits.

Tabitha

Reading this story, I found myself thinking that Sara was ridiculous and childish. I related more to Margaret, being an older, colder sister myself. While my sister, Annie, and I are extremely close now, she loves to give me grief from time to time. You were so mean, she’ll say. And I know I was. Growing up with an art therapist for a mother and a school teacher for a father, an air of gratitude and softness always hung in the house. Although this made for a loving, nourishing environment, I found myself feeling like an outlier.

My sister took after my mother’s gentleness in a way that I couldn’t and didn’t want to reproduce. I was a confident, competitive, selfish child that liked to fight and squirm. Sometimes I worried that anything nice that I brought to the table wouldn’t be quite right. Instead of risking it, I liked to be cold on purpose, so that when I was warm and soft, it seemed warmer and softer in comparison.

I imagine Margaret like myself in this regard, our younger sisters sometimes taking the brunt of our meanness. Sometimes little sisters make their big sisters into larger, more influential creatures than we are aware, clinging to our approval or disapproval, pride or disappointment. Seen as an all-knowing force, the actions of the older sister are analyzed and examined. The roll of an eye, turn of a back, a smile that seems it may have only been put on to appease the parents. The younger sister is susceptible to resentment, jealousy, loneliness, and shame. Combine this with a sister who hesitates to show loved ones her soft side, and the Saras of the world can wind up thinking they’re insignificant.

After a while the resentment builds up. The younger sister becomes too aware, noticing that she may have been made to feel small, but she, in fact, is not small. Sara began to observe that Margaret got special treatment at home and took advantage of it. “Everyone in the house made concessions for Margaret. [Sara didn’t] remember her carrying the same amount of responsibility for chores, and she always seemed to do things on her time. She made everyone wait for her and flaked out on a lot of commitments” (Leavy, p. 59).

Annie experienced this loss of faith as well. As her tween years crept in, the flawless version she had of me melted away. Soon, it felt like a switch had flipped; she went from wanting to be just like me, to wanting nothing to do with me. Though we still spent copious amounts of time together, she had a new overwhelming sense of disdain that I couldn’t swat or shake off of her. Just like Sara to Margaret, she came to see me “as selfish and narcissistic” (Leavy, 59).

When the younger sisters gain this acute awareness of your flaws, there are a few steps you can take, the simplest being divert. Divert. Divert. When Annie went: Tabitha gets everything she wants. Why does she get that new toy? I’d go: Annie, shut up, you just got this and that. It’s simple. Just throw it back in the youngling’s face.

However, I’d guess it wasn’t as simple for Margaret – the youngling being several years younger (rather than the two years between Annie and I) and presumably a pretty cute kid. When the diverting wears out, there isn’t much to be left with except an achy guilt. Then the little ones start fighting back. Regardless of age, any sister can be petty, spiteful, and jealous, at times, and simultaneously beautiful, hypnotic, and glorified.

I imagine that when Margaret left college and returned home from school for winter break, she felt guilt hit her when she walked through the door. She knew she had been mean to Sara, forgotten her, excluded her, left her out on purpose. Sara wouldn’t let her forget it. Every minute she spent in the house, she got glares; every time she brought up doing something together, she was met with passive aggressive comments. Oh, now you want to hang out with me? She wound up wanting to spend most days in her room, but even her room reminded her of the days she hadn’t spent there huddled up with her sister in front of the vanity. Dinners were the worst, sitting at the dining room table, Sara at the head, her eyes shooting darts.

You’re staying for dinner? Shocker. Margaret wanted to leave. Go back to school. Go back in time, teach herself to humor her little sister. She wanted this, not because she felt she had missed out on essential sister bonding, but, rather, if she had, then the guilt would be less. From across the table, Sara’s glare continued. You weren’t enough then, you didn’t care enough. You didn’t love me enough! Margaret imagined Sara telling her. The legs of the big, mahogany table were carved into claws that Margaret felt slashing at her legs, a punishment for skipping family dinners in high school. Her mother and Sara had bought the table together, and it was just another reminder of the bond they’d developed while she was away at college.

When their parents died years later, Margaret grieved in silence. The eleven siblings gathered to divide up their parents’ things and took turns choosing items. It was clear to everyone that Sara was gunning for the table. The table she threw tantrums at when it wasn’t filled. The table at which she took attendance. Margaret imagined her tallying up her siblings absences, spiteful and cruel, and choosing which one of them to punish. Bobby picked the desk. And, by some stroke of luck, Margaret drew next. If I pick this table, I win. She doesn’t get to own me anymore, own how I feel, how I grieve, to own my guilt. I pick this table, I pick myself. I forgive myself, she thought.

Though her sister would never speak to her again, she would be happier in her day to day life. She would feel herself becoming a gentler person.

Though I know my story with Annie will never end in silence, I do feel guilty from time to time about the way I treated her. We never had a dining room table to fight over, but we made due. When we were young, we’d spend our afternoons snacking and homeworking at our grandparent’s house. On warm days in the late spring and early fall we’d play hide and seek, tag, or boys vs. girls outside with the neighborhood kids. Kate was Annie’s age and lived right across the street. S

he was born three weeks after Annie and they joked they were friends even in our mothers’ bellies. The three of us soon spent weekends cooped up in bedrooms or basements playing pretend or going to pumpkin patches or running around playgrounds. Kate was pretty, pale with brown hair like Belle from Beauty and The Beast. She went to private elementary school and her things always seemed to be better than ours. Cuter, sparklier clothes, newer, funner toys – pets! Her house had a constant rotation of animals, from the new hamster Kate’s younger sister got, to the foster kittens, to the new dog they finally received after much pleading.

Fish came and went, and there was even a chinchilla or two for a time. Kate was an emblem of everything Annie and I wanted. She was also our dining room table. We competed tirelessly. Endlessly. Without ever seeing a hole at the end of the tunnel or a trophy to win, we fought to be her favorite. We competed over who could make her laugh the most, whose clothes she liked more, who could play pretend better. We didn’t want her to ourselves, necessarily, we just wanted to be in the lead.

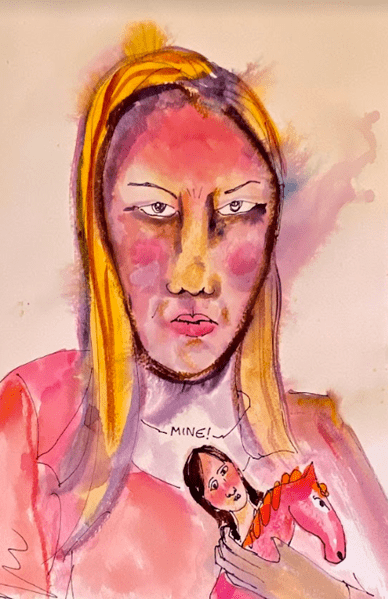

One Christmas morning, after opening presents at my grandparents’ house, Annie and I walked across the street to see what Kate had gotten. Once through her front door, we were greeted by a mechanical Shetland pony roughly the size of a Great Dane. It had fluffy golden fur and a soft cream-colored mane. The morning we’d spent opening presents from our parents at our house and driving the five minutes to our grandparents’ house to open more presents slipped out of our minds. This horse was the height of class, wealth, the best, most awesome present we’d ever laid eyes on, and everything else burned into non-existence in comparison. Then, Kate showed us that when you pet its head it neighed.

We were floored.

She let us mount the horse and pretend to ride it. And it got even better. Once sitting on the beast, its body began to move back and forth slightly as if it were galloping.

When her mother came in and saw us all playing on it, she gave us a weary look. “Girls,” she said, leaning on the wall in her fuzzy robe and Christmas pajamas. I was entranced. She was an extension of Kate. Though, genetically it was the other way around. “Take turns and be careful…” We promised we would. “And let your sister play with you,” she added.

“No!” Kate replied. Her sister was three or four years younger than Kate and absolutely never allowed to play with us or even talk to Annie or I. We were Kate’s toys, and no one else’s. I remember her sister, sticky-fingered and meddlesome, always a few seats away at the dining room table or next door in her room. We didn’t speak to her much.

As the hysteria of Christmas wore off and the morning waned into afternoon, Kate was getting bored. She had owned the horse since eight in the morning and her enchantment had worn off. She begged to go next door so that we could show her what we’d gotten, but we pleaded for one last ride.

With Annie already sitting on the horse, I jumped up to join her, but overshot it. Annie and I toppled to the floor, the horse with us. Kate began to scream.

“It’s okay, it’s okay,” I said, scrambling to get up, “there’s nothing wrong with it.”

Annie backed away as I lifted the horse up and placed it upright. The fact that I could physically do this was probably a decent indication that I was too big to be riding the horse.

“It’s fine, nothing’s wrong with it,” I said again.

Kate mounted the horse and stroked its mane. It neighed but didn’t move. I had paralyzed it.

“You broke it, you broke my Christmas present,” she screamed at us. I couldn’t tell who she was talking to, and I had a hunch that she didn’t either. I turned around to face Annie.

“Why’d you push me off? You broke the horse!”

“I didn’t!” she cried.

“Yes, you did!”

That went on for a while. By the end of it I managed to convince Kate that Annie did, in fact, break the horse. I could not, however, convince her not to tell her mom. I remember her scolding us lightly as she drank her coffee, but it was clear that she was trying to brush it under the rug and get back to the Christmas-day-do-nothingness. Kate did not come over to see our presents, she, instead, pouted in her room, playing with her other new toys. Our dining room table hated us, but I took pride in knowing she hated Annie more.

It may not have happened like that. Annie only remembers the horse and how cool it was. But I think of this memory as a testament to our relationship with Kate. Always trying to undercut one another, and drag each other down to bring our own selves up. Me, more than Annie, of course.

Sharing, not for me. Not for Sara either, she didn’t want to share Margaret, so Margaret didn’t want to share the table. For many, maybe most sisters, our things blur together into a murky one-ness. We fought over this one-ness, sometimes to get out of it and sometimes to stay in it. In the blurry, infuriating one-ness of sisterhood, I was never alone, always one of The Girls. Over the course of my life, this feeling has swung back and forth on the pendulum of positive and negative.

Full-fat and low-fat sides. The full-fat side says: You’ll never be alone! You’ll always have a best friend to go through life with, someone who understands things like no one else, someone who will always love you: someone who feels like talking to the voice in your head out loud. The low-fat side says: You’ll never be as amazing as your sister. You’ll always be looked down on and rejected. She would rather be alone than go through life with you. She will always be better than you and everyone knows it. I felt that it would stay on one side, for an hour, a week, a month, a decade, before swinging back. Margaret and Sara felt this, I’m sure.

The trick is figuring out how to keep the pendulum on the full-fat love side. It’s tricky to stay on the loving side of your sister; I feel we’re always teetering on the edge, sometimes tipping over for a second, and blowing up at each other over the littlest comments. “Did you button your shirt like that on purpose?” But we quickly find our way back to love. Some of us aren’t as lucky. The hurt from childhood has scarred over unhealed and the love has been low-fat for a little too long. Those sisters let go. They could never quite figure it out.

Gioia

Tabitha says I should write about her story. I don’t want to. Mothering is too hard, I can’t do it in public. I hated the times when my daughters would fight. Seeing Tabitha bully Annie just about broke my heart. I floundered to intervene, “Girls!” I’d snap, which had no effect whatsoever on their squabbles. I felt like a terrible mother. My mother-in-law started praying over her rosary for her granddaughters to get along.

Stepping in when their high voices started to rise, I made them list ways they appreciated each other until there was some resolution, a softening, a hint of humor or lightness in the way they interacted. Some days I just separated them and tried to distract Annie, letting Tabitha stew in her meanness. I thought it may have made sweet Annie tougher, as she learned to defend herself from the low-fat love. Somehow, thank God, Tabitha grew out of it in her later teen years, and the girls became close once again. Reading the story of Sara and Margaret, I was glad my girls found their way through their moments of estrangement to reconnect, stronger for it. Sara’s loss of her relationship with her sister was a narrative like many in the collection, that left me feeling so sad.

In the end, LFLS wasn’t one of my favorite Patricia Leavy books, even though it had lots of pictures. I suppose it’s because I’m an art therapist and listen to trauma stories for a living, then help people make trauma artwork to express the stress, I don’t really need to read or see any more suffering. Maybe I don’t need my consciousness raised, any more than it already is, about how women’s insecurities can eat them alive. Maybe this book should be read by those who aren’t as familiar.

My favorite novel of hers is actually Spark (2019). It is an enjoyable read about a bunch of researchers going to a conference in Iceland and thinking about the process of research and how it is we come to know anything. But my favorite Patricia Leavy book moment of all is actually from one of her textbooks. During my transformational first reading of Method Meets Art (2009), I suddenly, startlingly, saw myself —artist, art therapist, mom, compassionate person—reflected in the pages, and understood I was somebody who could do this kind of research. Right there on page 9, she acknowledged my people (art therapists) and the important link between arts-based therapies and arts-based research practices.

And then later, I met Patricia in the line for coffee at the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry conference, not knowing who she was, and she’s this cute chick with stylish hair and shoes (a rarity at academic conferences) who somehow was able to articulate this way of doing research better, better than all these white guys who’ve been running the show, and she’s able to describe things with utter clarity, making ABR simple: a research method, a path I could follow, clear as a bell.

Patricia—though younger than me—is like my academic big sister: a role model, fashionable, a bit slick, idealized, envied, lauded, beloved by many, someone who unfortunately-doesn’t-quite-have-time-for-you-when-you-surprise-her-by-showing-up-when-she’s-getting-an-award-because-she-has-a-book-signing-to-do, a bit of an icon, a star. You know, a big sister. But, as Tabitha wrote, sometimes little sisters make their big sisters into larger, more influential creatures than they really are. In proper big sister style, Tabitha had her set of grievances about LFLS. She wanted the narratives to be more nuanced with details and individuality. Grittier, she says. I wonder if because it was research and not entirely fiction, Patricia had to deprive us of the high-fat details and color in the images that might have made them truly delicious.

I’ve got a different take, as I’m the youngest in my family, the only girl, the special, odd one out who knows how it feels to be different. Like Annie, I’m sensitive and nice, an artist and art therapist, soft-hearted, or used to be. Patricia’s stories and Victoria’s art leaves my sensitive heart searing with imagery that haunts me. One character is covering her mouth at church so no one can see her smile because she’s so embarrassed about her teeth, while another is so, so very anxious about what to wear to a barbecue. Another character has so many dark thoughts about her body’s inadequacy, it’s like her face is ripping apart, a horrid image Victoria drew that I’m still trying to wash out of my brain.

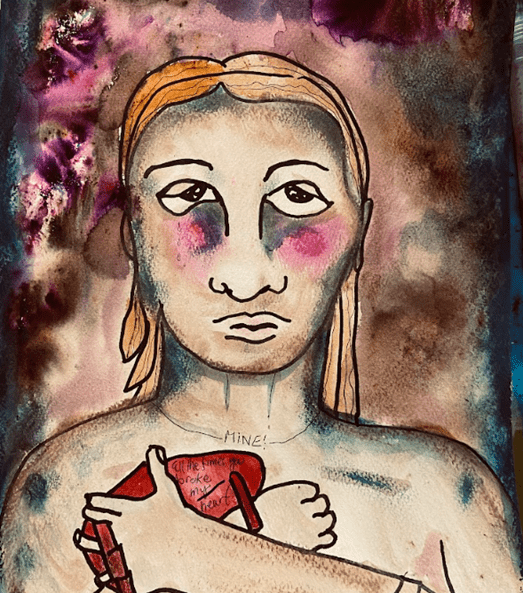

At the end, I felt I’d had too many shots of powerful alcohol, and became fuzzy and dazed, over time unable to notice the differences between each story. Drawing them, I felt better, the art expressing pain in a satisfying way. I used lots of intense color and didn’t try to make anything look good, just vibrant and expressive, sometimes adding handwritten quotes from the book and my own LFL thoughts scrawled over the images. I asked Annie, who is also an artist with serious Photoshop skills, and, as we know, very nice, to make my drawings into an animation to illustrate the impact this work made on us.

So as a mom, this essay turned out great for me as I got to discuss these powerful themes with my young adult daughters (and maybe I’m not a terrible mother after all?); while collaborating, I enjoyed their fresh Gen Z take on things. In terms of the book, as an educator, I appreciated the discussion questions, creative writing prompts, and artistic exercises tucked in the back, which Tabitha and I gratefully used as a jumping-off point for this piece. As a mental health professional, I would have liked to see the inclusion of some resources such as a list of websites and hotlines for support, so I’m adding them now.

| Wondering if you are in a low-fat relationship? Check out resources at https://www.loveisrespect.org/everyone-deserves-a-healthy-relationship/ and https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/relationships/healthy-relationships Don’t wait, if you or someone you love is in crisis, experiencing abuse, domestic violence, bereavement, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, or any other concerns in the US, call or text 988 now to connect with trained professionals. For international support, see https://findahelpline.com. By the way, if you feel like you’ve got too much low-fat love in your life, consider reaching out to a mental health professional to help you increase your love life nutrition! Find a therapist who you can trust: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/therapists or virtual https://www.talkspace.com/therapists.Maybe you’d like an art therapist? See https://arttherapy.org/art-therapist-locator/ Know you are not alone! Not quite ready for therapy with someone else? Or, having hard time accessing care? Try journaling on your own about what’s going on for 20 minutes a day for 4 days, and then see how you feel (Therapeutic Journaling – Whole Health Library a.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/tools/therapeutic-journaling.asp#:~:text=What%20Is%20Therapeutic%20Journaling%3F,we%20may%20be%20struggling%20with) |

As a researcher, I appreciated the transparency in the discussion of method, the clear outline of the phases of research data analysis/representation, and the interview guides which illuminated how the research was conducted. I also appreciated the accessibility and price point, one of the reasons why the images weren’t illustrated in color. Patricia shared that, “[she] wrote the book in part for those students and researchers who want to write creatively while still very much doing traditional research. [She] wanted to show the other side of the continuum of social fiction—its potential to mirror the qualitative research process and to produce work clearly grounded in data.”

Patricia told us that she offered participants copies of the book, but I still find myself wondering: What did they think of their emotional portrait by Victoria, did it capture something essential about their experience? Did they feel seen and heard? Did they gain a bit of empathy for each other, and for themselves? In this current version, Gioia and Tabitha are privileged to be able to chat up Patricia and Victoria and ask them what they think of our response to LFLS. But the original storytellers are opaque to readers and viewers. Without any of the original storyteller’s voices giving feedback on the final product, we don’t know if this work acted to reinforce negative self-image or was the kind of liberation art that awakened personal and social awareness, agency and action. I hope they look at this work and that it’s a bit of high-fat healing.

About the Authors

Gioia Chilton, Ph.D., ATR-BC, CSAC is an art therapist, artist, and scholar. Her writing has appeared in The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, Handbook of Arts-based Research, the Journal of Applied Arts and Health, and the Journal of Military, Veteran, and Family Health. With Rebecca A. Wilkinson, she co-authored Positive Art Therapy Theory and Practice: Integrating Positive Psychology with Art Therapy published by Routledge. Their textbook was recently translated and published in China by Chongqing University Press. Her book is available on Amazon: https://a.co/d/5yGfQsK

Tabitha Chilton is a writer and editor based in Virginia, specializing in creative nonfiction. Her work has been published in literary journals including The Foundationalist, West Branch, and Rainy Day.

List of Figures

1: Mine! Portrait of Sara

2: My Kate! Portrait of Tabitha

3: Taking my toys and going home.

4: Hush now, I almost smiled. Portrait of Keisha

5: I’m so embarrassed to call myself a feminist. Portrait of Jane

6: What three words best categorize your personal style? Portrait of Yael

7: I learned a lot about myself.

Credits

Images are provided by Patricia Leavy.

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.