Horror, Hate, and Hysteria: How to Survive the Exigencies of War

Author’s Memo

Born in Tokyo after World War II, half Japanese, I’ve lived most of my life in the Mid-Atlantic and Appalachian regions, and I write out of the consciousness that I am both a product of the violence of war and a migratory being—not only in the strictest sense of physical displacement, but also in belonging. How do I place myself in race? Asian-American is a convenience that attempts to pull together an identity fraught with conflict. Not only does it fail to distinguish among the many countries of Asia, but the hyphenation also reduces to meaninglessness the varied cultures and ethnicities.

In my life I have migrated from middle class to poverty and back again. To what class do I belong? And for how long will my present situation last? Fortunes change; they can be as fluid as gender, depending on choice. On circumstance. On the continuum of male-female, how do I say if I am this or that, male or female, when all my instincts and behaviors range, even within a single day? Like Whitman, I contain multitudes. The violence that inhabits these poems is the violence of war and rupture and self-doubt. It is the violence of language that attempts to say the unsayable, though I am compelled to bear witness.

hold on until the shaking stops

“Those poor little people, those poor little people.” Oppenheimer

Rolling thunder and the patter of the rain on

crayon-colored pictures of the sun a simple yellow

circle flashes bright through sieve of maples and

everything lights up electric from within the mind a deepening …

box of memories opens up the letters spilling out and sometimes

I am short vowel long tooth of the consonant that fats the boy

or girl who can’t go out to jump the rope to bridge the nose with wings

to fling the buckeyes bombing screaming between horses that are boundaries

we should keep I am small I am drinking chocolate milk out of

the spout eating tigers one-by-one from a red-and-yellow

circus with a handle sometimes I am zebra in my black-and-

white striped boots sometimes mute giraffe … letters in a language

to make sense of it sometimes I am crouched under the cover

of my desk ducking down between the lock of knees and making

myself smaller smaller though they tell us we are safe and sound

the sound of bell like an alarm our slickers hung on pegs like little

yellow skins of little people we’d discarded

I was waiting for my father to say his father’s name

His name

Falling down

Like this old house … this old house …

Made of splint and tinder. The curtains

Always drawn. Whiff of crematorium

Like grandma used to sing I will take you home …

Like confidential folk song

His name abandoned after war

Never talked about

My father changed his name on

All official documents

My mother said his father died

From eating too much sauerkraut

crush

When I pillowed dreams of boys who didn’t love me—boys

I would possess. White boys. Polish, Irish and Italian.

Everything about them strange. English Leather, denim,

when I serpented garages where they denned. Boys

who tooled in cars. Who spit on sidewalks. Boys

who moved in packs, who looked just like their dads.

There was the handsome-stupid boy who copied answers

to the tests. Another who made passes, spiked the winning baskets.

There was that boy who left the dance, who combed his hair

in the window of Pulaski’s. He was too beautiful.

I coiled in the hurt (see the footnote). White boys. Polish, Irish and Italian.

Here, I think you want me to say something like

geisha, kimono, cherry blossom—

Okaasan only said, Be sure he loves you more than you love him.

Here I reference Kiyohime (清姫), a character in Japanese folklore, who transformed into a serpent, crushing the monk who hid inside a temple bell after he had rejected her.

Credits

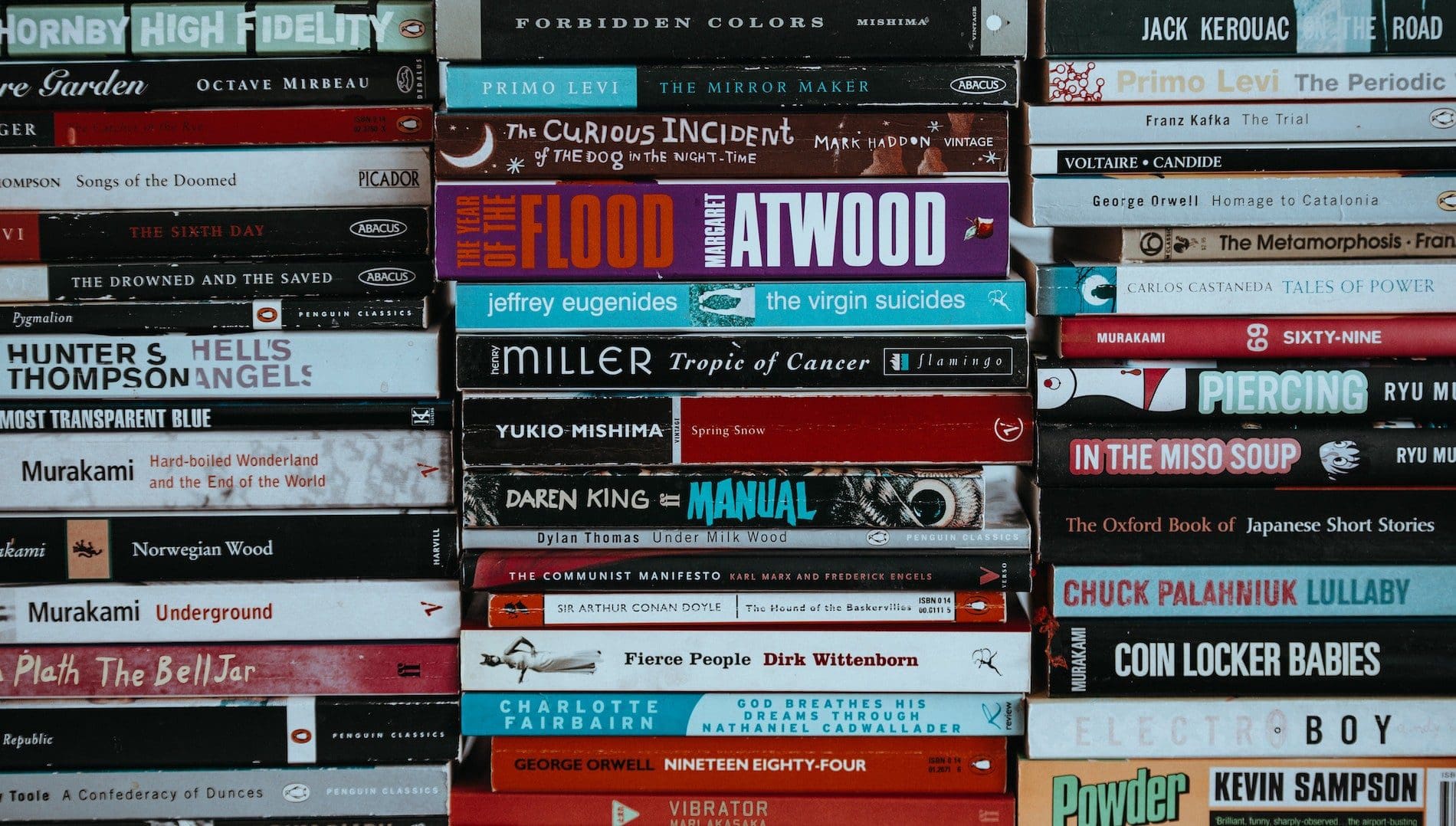

Image by Sahil Pandita for Unsplash

Featured Image by Jj Ying for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition

Born in Tokyo, half Japanese, Kathleen Hellen is an award-winning poet with three collections including Meet Me at the Bottom, The Only Country Was the Color of My Skin, Umberto’s Night, and two chapbooks, The Girl Who Loved Mothra and Pentimento. Featured on Poetry Daily and Verse Daily, her work is widely published and has appeared in such journals as Asia Literary Review, Frogpond, Hawai`i Pacific Review, Hawai’i Review, Kartika Review, Lantern Review, leaping clear, The Margins, Nimrod International Journal, Poetry International, Tokyo Poetry Journal, Valley Voices, Witness, and World Literature Today. She lives in Baltimore.