An Autoethnography on Autoimmunity: The Truth About Life with Chronic Illness

Author’s Memo

This work addresses the prominent issue of young women being underserved as healthcare patients, specifically through the lens of medical gaslighting. The piece takes a dive into my personal history with autoimmune disease and a cancer scare I had only last year. It examines the struggle and monotony of not being taken seriously because of age and gender. It also tells the story of a generational issue in healthcare that began with my mother as a chronic kidney disease and Lupus patient that continues on with me. As for how it is autoethnographic, the piece is directly related to my life’s experience and the research I have done regarding the topic.

This work addresses the prominent issue of young women being underserved as healthcare patients, specifically through the lens of medical gaslighting.

The piece begins with the detailed story of how I became sick as a child. I was eventually diagnosed with pediatric fibromyalgia but showed strong signs of Lupus. It goes on to describe my pain while waiting for the right medication and diagnoses. I was consistently told that my bloodwork was off, but not off enough to warrant intervention. The piece then discusses my deteriorating mental health, culminating when I was diagnosed with multinodular goiter, thyroid cysts that had a chance of calcifying. I touch on Eastern versus Western practices as I relate the tale of trying to combat my symptoms, including going on the Paleo diet. This ethnography is meant to show the trials and tribulations of autoimmunity in its purest form.

Steering away from myself, the piece talks about the experiences of other patients and doctors that have witnessed situations similar to my own. A detailed interview with my own mother demonstrates the complications of having autoimmune disease for over 40 years of her life. The piece makes known the importance of ageism and sexism in the healthcare industry, while also mentioning racism and settler-colonialism. However, since I am a white woman, I could not personally describe being discriminated against for my race in the medical setting. But the intersectionality of the issue still remains.

The piece takes a dive into my personal history with autoimmune disease and a cancer scare I had only last year.

I sincerely hope that you will consider my piece for publication. I want people to read my story and gain at least a slight understanding of what it’s like to live with a chronic illness at 20 years of age when I should be happy and healthy instead.

I have been shuffling in and out of doctor’s offices for as long as I can remember. The harsh white light and antiseptic smell is all too familiar. I walk in the revolving door, and the security woman stops me. “Weren’t you here earlier today?” she asks me. I tell her that I was here yesterday, and the day before that, and before that. That’s why she remembers me. She hands me a purple surgical mask and states, “Well, you know the drill then.” I get my temperature taken, walk into the waiting room and check in. I sit on the stained chairs, wait and watch as people much older than me come and go and I stare at my phone until the battery dies. Finally, I’m called in.

Sitting on the crinkled paper atop the examination table, I think about being a little girl in this same spot. For years I have been telling my multitude of doctors that something is wrong with my body. Every day I wake up, I am tired no matter how long I’ve slept. I’m sore regardless of whether I have exercised. I am never not in a constant state of pain and exhaustion. Yet, for so long, others sought to convince me I was experiencing normal life as a teenage girl.

I have been shuffling in and out of doctor’s offices for as long as I can remember. The harsh white light and antiseptic smell is all too familiar.

I spent years shouting into the void. Only to be told that I didn’t eat right, didn’t sleep enough, and didn’t exercise enough by pediatricians, specialists, and even friends and family. But I know myself. And so does my mother. Before I first got sick, I was running close to five miles a day. I was training for my school cross country team, eating often (and healthily), and sleeping eight hours every night. How could a team of healthcare professionals say I was fine when things had changed so drastically? The excuse was always, “Your bloodwork numbers are off, but not off enough.”

Luckily, my mother was knowledgeable enough to act as a strong advocate for my physical well-being. Struggling with her own intense health problems, which were problems she knew could be passed on to me, she begged the doctors for specific tests that might show something wrong. Her persistence paid off. On October 26th, 2018, I was diagnosed with pediatric fibromyalgia, a chronic pain disease with no cure. Memories of that day are utterly bittersweet. I remember feeling broken and defeated that I would be sick forever but simultaneously hopeful and relieved that I had some sort of answer. However, I knew even then that fibro was only the beginning of an even bigger issue.

I spent years shouting into the void, only to be told that I didn’t eat right, didn’t sleep enough, and didn’t exercise enough by pediatricians, specialists, and even friends and family.

In 2018 I was a junior in high school. I had so many exciting things to look forward to. And I was overjoyed that I would finally get some care that might improve my quality of life. I started a new medicine and physical therapy. Things were looking up despite the constant dread of being chronically ill. But things didn’t go as I had wished. Things got worse. I couldn’t get out of bed, had a fever every day and was taking loads of painkillers for aches that had no explanation. I told my rheumatologist and pediatrician that something else had to be wrong. Bloods were run, but it was the same old story. Nothing was wrong enough for anyone to notice despite my cries for help.

By the fall of 2019, I was in a dark place. From the day of my initial diagnosis, I was certain I had Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, just like my mother. My symptoms were almost identical to hers, and my condition was worsening. This self-knowledge morphed into a self-diagnosis that I was begging other people to recognize, to understand. I knew I didn’t have a medical degree, but my self-knowledge had to count for something. My words, thoughts, feelings, symptoms, and emotions surely should be counted as medical evidence, as bizarre as that may sound.

By the fall of 2019, I was in a dark place. From the day of my initial diagnosis, I was certain I had Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, just like my mother.

In the ethnographic world, auto-ethnographies such as this one are the foundation of anthropological knowledge. However, the prefix auto, while still meaning “self” in the medical world, will never not be inextricably tied to autoimmunity. The auto– of auto-ethnography and the auto– of autoimmunity shuttle the “self” into different domains of knowledge and power. While my immune system may be attacking me, the version of me that the word “auto” references is no longer me. I have been reduced to the sum of my parts that work incorrectly, with my thoughts, feelings, and human self tossed aside.

I brought these concerns to my rheumatologist, who said there was a strong possibility of Lupus. She said she believed my self-diagnosis could be accurate since every test that would indicate Lupus had come back positive, just at separate times. But until every test returned a positive result at once, nothing was to be done. Around the same time, I had recently stopped my fibromyalgia medication due to side effects and was not given a replacement. I was devastated. Everyone I looked to for guidance was of no use.

My mother and I cried together as I faced the reality I would never recover from a mystery illness no one wanted to acknowledge. In the winter of 2019 going into 2020, I was hospitalized so many times that I lost count. And still, no one came to my aide. I barely graduated high school and had to take a majorly reduced course load my first year of college.

My words, thoughts, feelings, symptoms, and emotions surely should be counted as medical evidence, as bizarre as that may sound.

During my high school experience and initial year of college, I endured the pain of waiting in a time frame known as “in the meantime.” Medical anthropologists Michal Frumer, Rikke Sand Anderson, Peter Vedsted, and Sara Marie Hebsgaard Offersen, in their piece “‘In the meantime’: Ordinary life in Continuous Medical Testing for Lung Cancer,” describe this as “characterised by a dramatic mode of being—that is, waiting for death—and an ambiguous mode of being: feeling quite well”.

And while I know I was neither waiting for death nor feeling well, I was still stuck in this horrible phase of being told to be patient and go on with everyday life, even with the storm clouds looming over my head. This was a cruelty that plagued me and still rears its ugly head even to this day. Being observed in pain with no provision of care feels like it should be used as a method of torture in warfare.

In the ethnographic world, auto-ethnographies such as this one are the foundation of anthropological knowledge. However, the prefix auto, while still meaning “self” in the medical world, will never not be inextricably tied to autoimmunity.

The winter of 2021 was a turning point in my medical story. Now 19 years old, I finally switched from a pediatrician to an adult primary care physician. About to finish an exceptionally challenging semester in terms of my health, I begged my doctor to do something, anything. I was willing to sacrifice essentially everything if it ensured feeling the way a young person is supposed to feel. And for the first time in my life, I finally felt like someone really heard me. My new primary care physician at WestMed Medical Group in White Plains, New York, told me that she didn’t care what any of the previous test results said. She knew there was a big problem and was determined to get to the bottom of it.

After weeks of testing, the doctor told me that Lupus was a strong possibility, but she didn’t think that was the only issue. She said she’d let me know her conclusions as soon as possible. Grateful for her attentiveness, I also wondered how much this shift to action had to do with switching out of medical pediatrics and thus out of a broader social category of girlhood.

The auto– of auto-ethnography and the auto– of autoimmunity shuttle the “self” into different domains of knowledge and power.

I remember being on the West Side Highway in Manhattan when I got the phone call that changed everything. Sitting in the passenger’s seat of my mother’s blue Volvo V90, I was given the news that I had some sort of liver disease. But even worse, the imaging of my thyroid came back to show several cysts. The doctor told me they were inhibiting my thyroid function as is, but if hardened could turn into thyroid cancer. I would have to be put under cancer observation, get routine imaging, and if, God forbid, I was to get cancer, undergo an operation to get my thyroid removed. I remember staring at the buildings above as I sat in silence for the rest of the car ride. And I couldn’t help but wonder if someone had listened to me when I was younger, maybe it would all be different.

Now here’s the sad truth: I am not the only young person this has happened to, nor the only girl this has happened to. I am one of the thousands of teenage girls who have had their pain minimized repeatedly. We are always simply “being dramatic” or “overreacting.” Not to mention, we don’t exactly fit the stereotype of what a disabled person looks like. Women’s healthcare has always been substandard. Our gynecological practices are archaic, causing many people, specifically Black women, to die during childbirth.

While my immune system may be attacking me, the version of me the word “auto” references is no longer me.

And young people are consistently told that they aren’t old enough to be having such intense problems, focusing on quick fixes like sleep. Put the two categories together, and you’ll see that being a young woman dealing with medical uncertainty proves an absolute nightmare. I know that living this way has personally impacted my mental well-being, and not in a positive manner. Thus, I wanted to conduct a research project focused on people like me.

This essay is based on my ethnographic observations, consisting of data regarding my own experience and that of others. I argue that medical uncertainty for women at a young age is highly detrimental to mental health. I also argue that the root cause of this can be traced back to sexist/patriarchal, ageist, racist, and even settler-colonial beginnings.

This essay is based on my ethnographic observations, consisting of data regarding my own experience and that of others. I argue that medical uncertainty for women at a young age is highly detrimental to mental health.

Further, by deeming the issue as such, we can work toward reforming healthcare in the United States and creating a system that won’t let people like me, the ones who have lived their life atop that examination table, fall through the cracks. To find evidence to support my arguments, I visited many field sites to collect information. The most prominent of these sites was the WestMed Medical Group location at 210 Westchester Avenue, White Plains, New York, where I have two doctors, and additional sites comprised my usual Urgent Care, laboratory, and radiology facilities.

The WestMed building sits on top of a small hill overlooking the city, with a large revolving door and a few stories. When you enter, you are immediately given a surgical mask ask screened for COVID-19 symptoms. If you look to your left, you’ll see a small desk of security workers stationed next to a tiny café. To the right, you’ll see the combined waiting room for the walk-in clinic and laboratory. The line to check in is often out the door. The chairs are greenish-yellow and stained all over.

I have been reduced to the sum of my parts that work incorrectly, with my thoughts, feelings, and human self tossed aside.

This is often where I spend most of my time since blood work appointments never seem to start on time. This is also where I asked a few patients about their experiences with health and identity. I inquired about the following: What are you seeing the doctor about today? If you have a chronic problem, at what age did the problem start? Do you feel like you’ve received adequate medical attention throughout your life?

Most people at WestMed are significantly older than me, so I knew I would get some responses that differed from my own experience. Many people said they were there for routine blood work after check-ups, while others stated they were having specific tests done for specific issues. Of this second group, all older men said their health problems started later in life and they felt nicely taken care of. The women in this group mostly agreed, though there were a few outliers.

One woman, who preferred to remain nameless, explained that it took her many years to get diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis even though she experienced significant pain for a frustratingly long period of time. When asked about her opinion on why that was the case, she stated that she knows autoimmune diseases like RA and Lupus can take a very long time to diagnose and properly treat. Regardless, she wished it could have worked out on a more accelerated timeline.

We are always simply “being dramatic” or “overreacting.” … Women’s healthcare has always been substandard.

I deeply considered this woman’s thoughts. Perhaps she was right – maybe autoimmune disease is the root of the problem. After all, we know so little about autoimmunity, its causes, and its effects on the body. However, I remained unconvinced that insufficient knowledge about certain diseases was the more significant issue. While it may play a role, it still doesn’t explain the treatment of women in the healthcare system, as no men I talked to shared the same understanding, and the woman suffering from RA wasn’t as young as me. Ergo, I knew I had to further the investigation elsewhere.

My next important field site was the Eleven Eleven Wellness Center in Manhattan. At the center, I see Dr. Frank Lipman, an alternative medicine doctor specializing in gut health. I started going to him to supplement the care I was receiving with my primary care physician. I have found that gastrointestinal health is a big part of recovery, even though Western medicine doesn’t agree.

Dr. Lipman, when I first met with him, explained that fibromyalgia, Lupus, my liver problems, and thyroid nodules could all be attributed to my poor gut microbiome. Essentially, I have an overarching condition known as leaky gut syndrome. It means I don’t have the proper enzymes and microbes in my intestines to break down food. Because of this, particles are leaking out of my intestines and flowing into my bloodstream, causing all types of issues. I am currently on seven new supplements to combat this as well as a rigorous new diet.

Medical uncertainty for women at a young age is highly detrimental to mental health… The root cause of this can be traced back to sexist/patriarchal, ageist, racist, and even settler-colonial beginnings.

I was amazed to learn this fascinating new information. As I sat in his tiny office overlooking the Flatiron district, with the office puppy at my side, I asked him why I had never heard anything about this before (at least outside of my science, technology, and society class). He replied that it’s mainly an issue with Western medicine as a whole. The West doesn’t view the body as one singular being but rather as a collection of organs that each has its own functions. Because of this, many Western doctors cannot make important observations about how body parts are connected.

This had me thinking about the trials and tribulations associated with autoimmunity. Perhaps the United States is simply falling victim to a trap in which their medical knowledge is severely limited, causing a trickle-down effect where an individual’s life is impacted. Yet, this still does not shed any light on why women and younger people are disproportionately affected by this issue. I asked Dr. Lipman his thoughts on the matter. He stated, “All I know is that I see plenty of young women just like you with similar issues. They say they have Lupus, fibromyalgia, etc., which is true, but it’s not the main problem. So many young women come to me having found no relief, but then I help them out.”

I found it significant that he has so many young women as patients and their years of no solace. I’ve had many doctors tell me that they know so little about autoimmune diseases, that autoimmunity is mysterious and complex. Are our colonial medical systems failing us? Yes, but maybe not even for the reasons Dr. Lipman described.

“All I know is that I see plenty of young women just like you with similar issues… So many young women come to me having found no relief, but then I help them out.”

Insufficient knowledge as a scapegoat seems like nothing more than a political tool. The United States healthcare system is for profit. Drugs are created to make money. A drug can be produced for a few dollars and subsequently sold for 20 times that production cost. And this is how wealthy corporations, wealthy politicians, and wealthy people want things to stay. Perhaps the substandard care for autoimmune diseases in women, including young women of color, reflects the tacit acceptance that this will bankrupt people and further drive social and economic inequity. It’s a lot to think about. Keeping these thoughts in mind, I moved into my final stage of research, hoping to get some specific input from women whose mental health and quality of life I knew had been severely impacted by their conditions.

My final field site was the living room of my Tudor-style house in White Plains, New York. Here, I conducted an interview with my mother, Bernadette McNamara-Leccese, on her personal experience with medical uncertainty as a young woman. I asked her to share a bit about her story. And she explained that in 1984, when she was 16 years old, her kidney issues began when she started urinating black liquid. She had a biopsy performed and was given a very broad diagnosis. However, she just now learned that her original diagnosis was wrong. Bernadette exclaimed, “Here I am, 40-something years later, finally getting the treatment I need to hopefully preserve my kidney function, which is below 50%. It also took me until I was 40 to get diagnosed with Lupus. I have a new kidney doctor since my old one just retired, and she’s amazed at the situation.”

Insufficient knowledge as a scapegoat seems like nothing more than a political tool.

When I asked her if she felt her gender and age at the time had anything to do with the care she received, she said the following: “Because I present the way I do, I was told that I was fine by all the male doctors. I felt like I wasn’t taken seriously with all the pain and suffering I was going through/am going through. If I had a broken arm or leg, something visible, it would have been different. But this was psychological warfare. I knew something was wrong; I was in and out of the hospital so many times. But each time I would get better, they would send me on my way.

There was a doctor of mine. I don’t want to give his name, but I remember it clearly—say ‘This is female stuff.’ I was being looked down upon as a female because I was complaining about ‘lady stuff’ when I was seriously suffering from a debilitating disease. Even at Cornell in NYC, no one could help.”

‘This is female stuff.’

Her words deeply affected me, as I’m currently going through a similar situation with my thyroid. And since Bernadette is my mom, I felt even more upset. I concluded the interview by asking her if she thought anything has changed as she got older. She replied, “People only take me more seriously now, at 60, because I am my own doctor and advocate for myself, as well as because of my experience in the medical field and medical advertising. I became friends with doctors. I pushed for myself.

Medical advancement plays a role, but female doctors are also so much more helpful and validating.” I feel like Bernadette’s words speak volumes about the overall message of this project. The United States healthcare system is failing young women, and the impact is disastrous. I can only imagine what my mom’s and my own lives would be like had we only been taken seriously from the start.

Mentally, the pain of it all is unbearable. Nowadays, there is a big focus on taking up “self-care” as a lifestyle. All over the internet, one can find tips on how individuals can improve their well-being. Even if the growth of “self-care” rhetoric might reflect a failing medical system, in which people are not receiving care, suggestions often include things like pampering oneself by using a face mask or splurging on an expensive, extravagant coffee to self-soothe. But for people like me and my mom, improving well-being can only come from this agonizing method of self-advocacy and shot-in-the-dark attempts at self-preservation. This is our twisted version of “self-care.”

Mentally, the pain of it all is unbearable. Nowadays, there is a big focus on taking up “self-care” as a lifestyle.

We deserve better. All the young women of this country deserve better. Like my mom said, it’s psychological warfare feeling one way but having everyone else in the world tell you that you’re crazy. The clinic is my battleground. It’s chaotic, guerilla warfare. It has the kind of asymmetry where one side holds immense strength but the other is made up of irregular, comparatively marginalized personnel. Or maybe it’s Spartan warfare, where I’m a soldier for the medical industry who’s been placed in the front row of the phalanx formation because I’m the weakest. I’m disposable. Replaceable.

But even if no battlefield is ever neutral, this battlefield is additionally raced, classed, and gendered. And I still have the privilege of knowing something is wrong. I am lucky to know that my form of self-care is an unfair burden, to be aware that I’m deliberately put in a dismissible position. And yet this is a position from which I know, and I am determined to use my knowledge to alter the terrain on which people fight, differentially, for care.

****

This research project enraged me but also empowered me. I am angry about how I have been treated, how my mom has been treated, and how countless other young women have been treated. But I am also determined. At the end of this, I am left with the sense of drive to advocate for the health of young women, specifically those suffering from autoimmune diseases and cancer. It’s very probable that our problems could have been prevented, and for that, we must make a change. My research shows that we need more than more medical studies of autoimmunity (though we also need that.) We need to begin a national campaign explaining the reality of the pain of young women. It is also important to note that if this is my experience as a white woman, the experience for women of color is almost certainly even more concerning.

Furthermore, we must step away from our colonizer worldview that the West is the best and adopt alternative medicinal practices and other knowledge traditions to combat autoimmunity. And insurance companies must cover them. This way, the young women who have been underserved can have some sort of relief. I will continue to fight for young women’s mental health and quality of life. Ethnography always goes back to the question of the everyday, and I am tired of this being my every day. I am tired of the white light, the antiseptic smell, the stained chairs and the security woman recognizing me as I walk into the doctor’s office. I will stop at nothing to get the justice we deserve atop the examination table.

CODA

It is currently August of 2022. My primary care physician (who will no longer be my PCP after telling me to “be grateful I’m not as sick as her son”) told me that my thyroid nodules were 0.2 cm away from being a problematic size this past June. Despite this alarming news, she said we would wait six months to do another thyroid scan even though those measurements had been taken in December 2021. I was deeply concerned. What if my nodules had grown? What if something had calcified? I made an endocrinology appointment anyway and got another scan done that wasn’t covered by insurance.

While there was no change in my nodules, I am still glad I pushed to get myself care. If you can even call it that. I went in for a test and received nothing else—no effort from them to try and alleviate my symptoms. I’ll go back in one year for another scan to continually ensure I don’t have thyroid cancer. I am again waiting “in the meantime,” this time as a potential cancer patient, just as Frumer et al. described.

While there was no change in my nodules, I am still glad I pushed to get myself care.

On the bright side, my symptoms have greatly improved thanks to Dr. Lipman’s diet regimen and new medicines. I am grateful for his attention to detail, excellent bedside manner, and selfless work. As for my mother, Bernadette had a new biopsy done on her kidneys in July, the first one done since the initial biopsy in 1984. Her body has been under immense stress. We are still waiting for the results. The pathology department at the hospital where the operation was performed may have lost her results. She’s looking into getting a new new kidney doctor after her current “new” doctor shouted to her on the phone, “I don’t know what you want me to tell you about your results. I don’t have them.”

If the results aren’t found, my mom will never know if her initial kidney diagnosis was wrong and how to get proper treatment. And she can’t do another biopsy ever again since her kidneys are too traumatized. She is also waiting “in the meantime.” I am devastated for her. And though things have been looking up for me, I’m sad for myself too. For my whole self, a cohesive “auto” who is more than a subject of autoimmunity and contemporary US medicine’s failures of care. Utterly sickening, no pun intended.

Works Cited

Frumer, M., Andersen, R., Vedsted, P., & Offersen, S. (2021). ‘In the Meantime’: Ordinary Life

in Continuous Medical Testing for Lung Cancer. Medicine Anthropology Theory, 8(2), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.8.2.5085

Credits

Featured image by Mohamed Nohassi for Unsplash

A woman in a sunflower field by Motoki Tonn for Unsplash

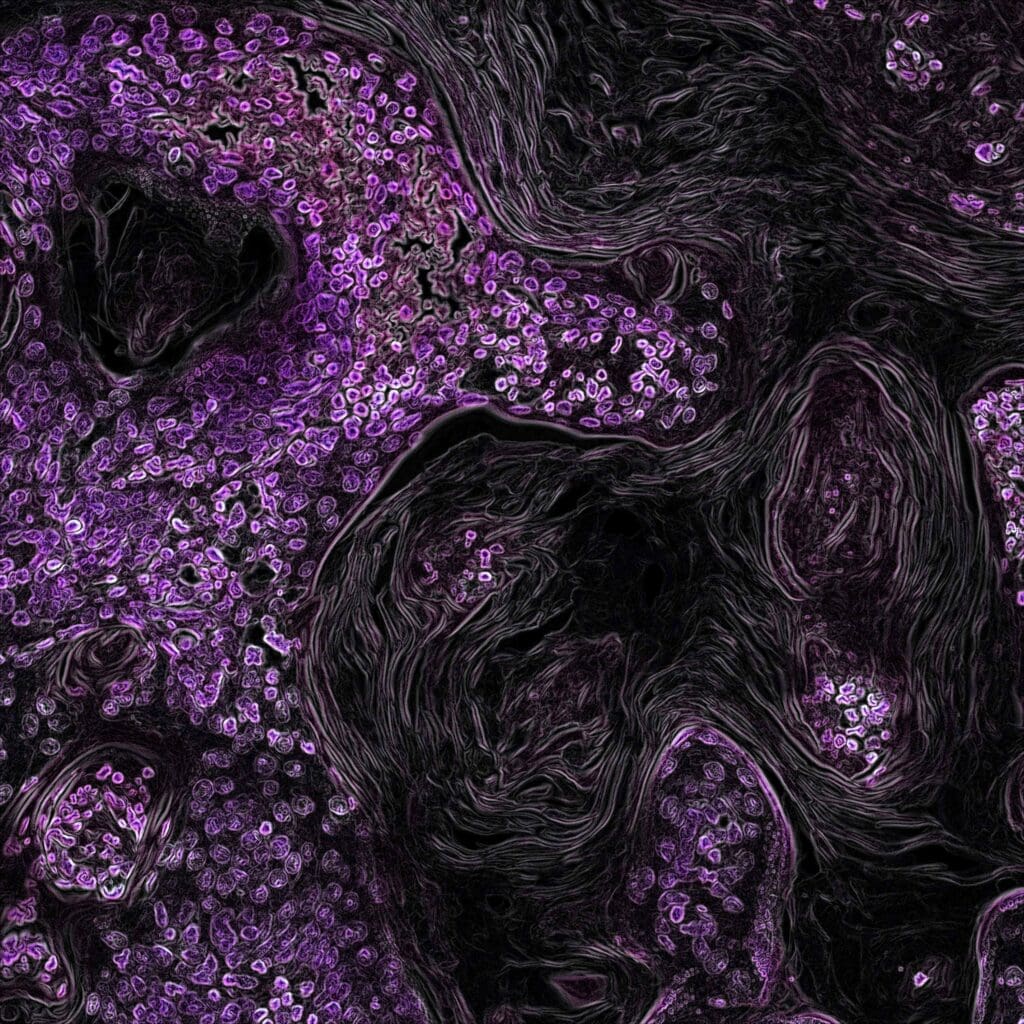

Purple flowers by National Cancer Institute for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Kerry Leccese (she/her), proud autoethnographer of autoimmunity, is a senior at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ. Kerry is diligently working toward a Bachelor of Arts in Social Science with a minor in Philosophy, as well as a minor in Science, Technology, and Society Studies. Her expected graduation is in May of 2024. Kerry is incredibly proud to be receiving her degree despite the challenges she has faced with her physical health.

Kerry is an aspiring mental health professional who currently works as an Eating Disorder Recovery Coach at Monte Nido and Affiliates. Her goal is to one day obtain a Psy.D. degree and become a child psychologist. To Kerry, helping people is the most important thing in the world. She hopes her career can reflect that.