Social Fiction: How Leavy Pioneers a New Genre

I was thrilled when I learned about Patricia Leavy’s innovative Social Fictions series. Having published over twenty academic books, I was beginning to write fiction. Fiction intrigued me because, as Kathleen Alcalá (2007) put it, fiction “seeks to capture truths that cannot be contained within the parameters of unadorned facts” (p. 42).

For decades, the unadorned fact in my academic writing has explored the workings of race, ethnicity, social class, gender, and disability in the everyday life of schools and classrooms, the identities of teachers and students, and power struggles over education policy. My data consists mainly of classroom observations and interviews, carefully analyzed and contextualized within relevant social theories. But as a teacher working with university students and classroom teachers, I knew that stories prompted deep reflection in a way that data and theory did not. Stories capture experiences and emotions; my students remembered stories long after forgetting social science data.

Fiction intrigued me because, as Kathleen Alcalá (2007) put it, fiction “seeks to capture truths that cannot be contained within the parameters of unadorned facts” (p. 42).

What first launched me into writing fiction was the process of making sense of my family’s history. I delved into family history research initially because I did not know my family’s own story, and I discovered a treasure trove of clues available on the Internet. As I discussed with friends and colleagues what I was learning, I began to recognize insights in the stories I was putting together that could not be communicated well through academic writing. For example, what would my German American ancestors have felt when forced to stop speaking German during World War I? Could their experience have paralleled that of Arab Americans following 9-11?

How many teachers might have similar experiences in their own family backgrounds, and could tapping into those experiences build their sensitivity toward cultural and language heritages of their own immigrant students? I found that, in Lake’s (2010) words, “It is through the power of personal story that we are able to move out of the essentialist/relativist dichotomy, out of abstraction and into the domain where each individual path of experience is incomparable and immeasurable in one aspect, but also universal in terms of sharing human life” (p. 43).

‘But as a teacher working with university students and classroom teachers, I knew that stories prompted deep reflection in a way that data and theory did not.

So, I began learning to write fiction that connects storytelling involving romance and moral dilemmas with dives into U.S. history and classroom praxis. I wanted to provide experiences in which teachers would feel themselves propelled along a learning curve as they grappled with the racial and ethnic diversity in classrooms and in our families’ pasts. I also wanted white readers to venture vicariously into conversations that perhaps felt too dangerous for them to undertake in real life and I wanted readers to plunge briefly into the well of guilt and pain that often consumes us as we confront our own positions within oppressive relationships, then to see a way forward through to constructive social action that an ordinary individual can undertake. In the words of wa Thiong’o (1983),

The pen may not always be mightier than the sword, but used in the service of truth, it can be a mighty force. It’s for the writers themselves to choose whether they will use their art in the service of the exploiting oppressing classes and nations articulating their world view or in the service of the masses engaged in a fierce struggle against human degradation and oppression. But I have indicated my preference: Let our pens be the voices of the people. (p. 69)

From Inspiration to Publication

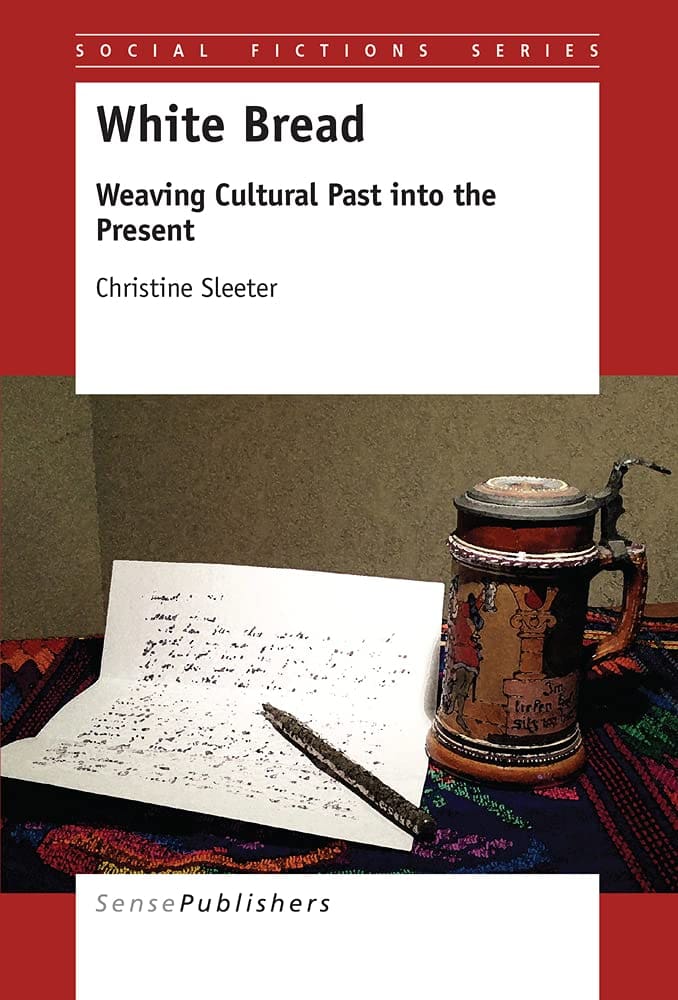

My first novel, White Bread (Sleeter, 2015), grapples with white people’s common ignorance about the loss of our immigrant ancestors’ cultures and languages, as well as loss of our own history. The novel features Jessica, a fifth-grade teacher in a culturally diverse school. At the beginning of the novel, she describes herself as “white bread” as she dismisses the significance of the cultural and linguistic heritages of her immigrant students. But discovery of an old letter in a box of her deceased mother’s papers launches Jessica into an exploration of her German American family’s history.

In the process of confronting the pain her ancestors experienced when their pasts were erased by U.S. policies and citizens’ fears during World War I, she realizes that this form of erasure still exists, and that as a teacher, she is a participant in it. What should she do? This is a question I wanted readers to begin to ask about their own families’ pasts and their work today.

‘I found that, in Lake’s (2010) words, “It is through the power of personal story that we are able to move out of the essentialist/relativist dichotomy, out of abstraction and into the domain where each individual path of experience is incomparable and immeasurable in one aspect, but also universal in terms of sharing human life” (p. 43).

But there was a problem: Who would publish such a hybrid of fiction and academic theory? Trade publishers typically look for potentially award-winning stories that are written for the general public, stories with dynamic characters who are driven by strong motivations, face enormous challenges (often of a life and death nature), and change over the course of the story. My protagonist did change through my novel. But the story emphasized change in her social consciousness, and the stakes were not life and death.

Trade fiction should be written for a large market of readers who purchase books of that same genre. What genre was White Bread? It seemed to combine social issues with fiction, a genre not present in most lists of literary genres. Yunus (2013), in an address to the Skoll World Forum, pointed out that while science fiction has a robust history of prompting technological change, we have so little social fiction that social problems go unaddressed. He said: “If we imagine today the kind of world we want, then that’s the kind of world we create.” Change will happen “when we create social fiction like we create science fiction.”

But the story emphasized change in her social consciousness, and the stakes were not life and death.

But social fiction does not appear on most lists of literary genres, leaving me to wonder: Do I try to market my work as general fiction? As women’s fiction? As multicultural fiction? After writing dozens of query letters to literary agents, and receiving either rejections or (more commonly) nothing, I felt discouraged until I learned about Patricia Leavy’s Social Fictions series. Leavy describes the series as coming out of arts-based research, and as “the first and only academic book series to exclusively publish full-length literary works (novels, short story collections, poetry collections, plays, and other creative writing)” (Social Fictions series page.) She aptly named the series “Social Fictions.”

Yes! Arts-based research that takes up social justice issues and transports readers into a world that involves them in unpacking and acting on social issues. Let us look at how some of the books in the series exemplify social fiction.

Leavy Pioneers Social Fiction

The series was conceived in 2010 and inaugurated with Leavy’s ground-breaking novel Low-Fat Love (2011/2015/2021). Low-Fat Love explores why many women settle for unsupportive and sometimes self-destructive relationships. These include relationships with men who are not emotionally available or supportive, relationships with family members that take second or third place behind work, and relationships with other women that become competitive rather than caring.

The novel explores a theme in many of Leavy’s novels: why so many women underrate themselves, depend too much on male approval, and as a result, settle for constricted visions of who they are and the lives they can live. The novel features two protagonists who work for the same publishing company in New York, as well as assorted other characters who also struggle with relationships. The character I followed most closely was Prilly Greene. She falls for an egotistical but charming and eye-catching aspiring writer who, over the course of the novel, brings her more grief than joy. In the end, she learns to see through him and to walk away from him.

‘Low-Fat Love explores why many women settle for unsupportive and sometimes self-destructive relationships. These include relationships with men who are not emotionally available or supportive, relationships with family members that take second or third place behind work, and relationships with other women that become competitive rather than caring.

Low-Fat Love is a page turner that exemplifies arts-based writing grounded in sociological research. As Leavy explains in the preface of Low-Fat Love, this novel:

is grounded in a decade of research and teaching about gender, relationships, and popular culture, which informs the pop-feminist undertone of the book. For a decade, I conducted interviews with young women about their relationships, body image, and sexual and gender identities. Additionally, I taught many college courses on the sociology of gender, critical approaches to popular culture, and human sexuality and intimacy. (Leavy, 2015, p. xx)

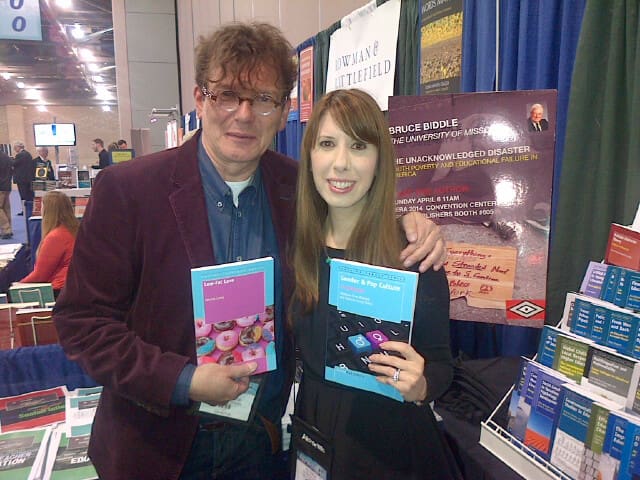

The novel puts flesh onto themes captured in Leavy’s research and teaching, as well as fictionalized versions of her own personal experiences. It shows us what arts-based research can look like. As the publisher Peter de Liefde wrote in a foreword to the novel’s anniversary edition, with its release in the summer of 2011, Low-Fat Love “quickly became our best-selling book.” He added that Sense Publishers was “proud of the Social Fictions series, which has become our most popular and fastest-growing series” (Leavy, 2015, p. xvii).

‘…in a decade of research and teaching about gender, relationships, and popular culture, which informs the pop-feminist undertone of the book.

I should note that four editions of Low-Fat Love have been published to date. Low-Fat Love (Sense, 2011), Low-Fat Love: Expanded Anniversary Edition (Brill/Sense, 2015), Candy Floss Collection: 3 Novels (Brill/Sense, 2020) and Low-Fat Love: 10th Anniversary Edition (Paper Stars Press, 2021). Low-Fat Love has also been contracted for foreign translations. Leavy considers the 10th anniversary edition the definitive version of the book. Drawing on a decade of experience as a novelist, she thoroughly revised the novel and wrote a new ending. She explains in the afterword it is the version she always hoped to release.

Leavy has published several additional novels in the series. I have enjoyed reading them, and will comment on Blue, published in 2016, which acts loosely as a sequel to Low-Fat Love. Blue lifts up a secondary character—Tash Daniels—from Low-Fat Love, focusing on her life and choices several years later. Leavy explains that initially she didn’t like Tash. “She wasn’t the kind of person I would typically want to be friends with. Petulant, spoiled, superficial, attention-seeking—these are all ways one could describe her” (p. 133). But by focusing on Tash, along with other characters, Leavy probed the inner complexities of a person who, on the surface one may dislike, but gradually learns is struggling with issues below the surface. Quite often, that person has positive inner characteristics that go unnoticed when the annoying behaviors take center stage.

‘The novel puts flesh onto themes captured in Leavy’s research and teaching, as well as fictionalized versions of her own personal experiences.

In Blue, Leavy asks what happens when a woman who has made bad choices about relationships encounters a man (Aiden, in this case) who treats her well. Does she recognize his worth? Does she recognize her own worth through the way he sees her? Or, do her previous negative encounters constrain her ability to believe in herself and connect with him? As another character observed about Tash, “Tash is always in and out of relationships. They never last, but she’s sort of a love junkie…” (p. 110).

In the end, by struggling with her feelings and the impact of her choices on her life, Tash reevaluates her life goals and her stance toward men. She decides to take a chance on trusting Aiden. Her developing sense of her own worth, and her willingness to try trusting someone else, does not come easily. But as readers journey with Tash, they are challenged to examine and question their own insecurities and adaptations that may, in fact, serve them in dysfunctional ways.

Leavy returned to the character Tash Daniels in the award-winning novel, Film (2020), which follows Tash and new characters a few years later. In 2022, she released Film Blue, the complete and definitive Tash Daniels story. The novel received high praise from scholars including Sut Jhally, Jean Kilbourne, and Norman Denzin, and has been recommended for inclusion in college courses that deal with gender, pop culture, or media.

The Series

The Social Fictions series features novels and other works that grapple creatively with wide range of social issues. October Birds (Gullion, 2014), for example, follows a pandemic from the person who brings a new influenza virus into the U.S., through many deaths and the frantic efforts by first responders and health care workers to contain the virus. Each chapter of this well-written page-turner opens with a tally of the total number of people infected and the total number dead in the fictional city of Dalton, Texas. We quickly go from one infection and zero deaths in Chapter One, to 15,769 infections and 636 deaths in the last chapter.

The author, Jessica Smartt Gullion, served as Chief Epidemiologist in a large public health department in Texas. In the book’s preface, she explains that the novel draws on her experiences with epidemics, most notably H1N1 in 2009. Initially, it was unclear how deadly this flu virus would be. It turned out to be serious, but not the deadly global pandemic that was initially feared. Gullion explains that, “While our goal was to prevent as much illness and death as possible, we were accused of over-response and our actions criticized” (p. ix-x). Prescient words, given the Covid-19 pandemic that would come along ten years later.

‘October Birds (Gullion, 2014), for example, follows a pandemic from the person who brings a new influenza virus into the U.S…

In October Birds, Gullion explores the social interactions among health care workers at the community level, particularly what kinds of things go wrong and why, and mental health strains that they experience. Her intention is to prompt readers to envision a system that works better. “Through fiction, we can imagine alternatives to our current social structure. We can explore what happens when the structures that seem concrete crumble around us. We can answer the question: ‘What if?’ using sociological research and practice” (p. xi). Perhaps if fiction like October Birds were used more widely in discussions of public health, some of the harmful disinformation surrounding the Center for Disease Control’s efforts to contain the spread of Covid-19 could have been tamped down, and perhaps there would have been deeper appreciation for the tremendous efforts made by health care workers.

Blood into Water (Clair, 2021) presents a fictionalized conflict in Nicaragua over a corporate attempt to privatize water, and the resulting social movement to resist that attempt. In the novel, Clair peels back layers in this conflict, enabling readers to immerse themselves in its complexity. For example, should a company that removes pollutants from water be able to make a profit from their work? Clair also situates this fictionalized conflict within a long history that is revealed in a myth about a queen who lived during the sixth century, “a time period in which it is believed that droughts led to warfare that contributed to the near extinction of the Maya” (p. xi). Water scarcity had been a source of conflict for many generations. While Clare invented the myth, she based it on a true story of the discovery of a stela in Guatemala that depicted a similar queen.

‘We can explore what happens when the structures that seem concrete crumble around us…

The author explains that the novel “was originally inspired by the true story of the ‘Bolivian Water Wars’ in which a corporate conglomerate, in cahoots with the government, tried to privatize the water of Bolivia” (Clair, 2021, p.xiv). She also details several other issues embedded in the novel: the complicated relationship between the U.S., the Nicaraguan government, and protestors against the government’s policies; foster care; and the relationship between the U.S. war on drugs and the lucrative nature of illegal mining.

Like the authors of other books in the Social Fictions series, Clair describes the extensive research on which she based this novel. She also includes characters who teach the reader more about the issue of water and the environment. For example, readers accompany Caleb, one of the protagonists, to a lecture given by his contact, Professor López, who describes in great detail the kinds of chemicals that collect in water and processes for removing them. Delta, another protagonist, shares her extensive knowledge about Mayan mythology in the process of trying to recover ancient artifacts. Through this novel, a reader learns much about the impact of capitalist greed on people, and how U.S. policies toward Central America complicate rather than support struggles for social justice.

‘Like the authors of other books in the Social Fictions series, Clair describes the extensive research on which she based this novel. She also includes characters who teach the reader more about the issue of water and the environment.

Not every book in the series is written as a novel. In Heartland (Simon & Simons, 2014), playwrights Lojo Simon and Anita Simons dramatize the internment of German-Americans during World War II. I discovered this book in the course of researching the suppression of German American culture and language during the two world wars as part of my own family history research. Although none of my ancestors was interned, I had become aware of this little-known part of United States history. As the authors of Heartland explained, after the Japanese bombed of Pearl Harbor:

President Roosevelt also issued Executive Order 9066, under which approximately 117,000 Japanese, Japanese Americans and their families were forced from their homes and confined to isolated relocation camps. . . .Less well known is the fact that the U.S. government also detained nearly 11,000 German-Americans and 3,500 Italian-Americans under the alien enemies law. (Simon & Simons, 2014, p. 3-4)

Set in rural Wisconsin in 1945, the play is based on true stories of German-Americans who were interned during the war. It not only reveals an ugly chapter in U.S. history, but it also humanizes both Germans and German-Americans. In the play, a German-American family becomes acquainted with a German prisoner of war who is sent to work on a dairy farm. The play offers poignant stories of people in an oppressive situation who initially distrusted each other, but gradually develop relationships of kindness and empathy.

‘In Heartland (Simon & Simons, 2014), playwrights Lojo Simon and Anita Simons dramatize the internment of German-Americans during World War II.

The authors provide several suggestions for using the play in the classroom, such as using it to teach about the Alien Enemies Act and the impact of its implementation on people, or the “American internment policy and Roosevelt’s decision to identity and imprison Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants and American citizens” (p. 9). The book directs teachers toward additional sources of information that might be useful in creating lesson plans exploring German American internment. As such, the book exemplifies purposes of the Social Fictions series: it teaches readers about a social justice issue, it engages readers in experiencing that issue vicariously, and it outlines how educators can use the book with their students.

My first novel White Bread was published in the Social Fictions series in 2015, and an anniversary updated version was published in 2020. In the anniversary edition, I developed a couple of the characters in more depth, and created a family tree that tied the various historical characters together more clearly. That edition also included a discussion of how one might use the book in a college course, written by two faculty members who had done so (Buchanan & Mills, 2020).

The authors provide several suggestions for using the play in the classroom, such as using it to teach about the Alien Enemies Act and the impact of its implementation on people, or the “American internment policy and Roosevelt’s decision to identity and imprison Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants and American citizens” (p. 9).

In 2021, I published a second novel in the Social Fictions series, Family History in Black and White. This novel traces two urban high school principals as they compete for a job as superintendent of a small neighboring school district. Roxane, who is African American, exemplifies visionary thinking and deep connection to communities of color that has served her well as a classroom teacher, and now as a school leader. Ben, who is white, exemplifies an exacting but humanistic approach to school leadership that relies on building partnerships with local businesses. For different reasons, each begins to trace some aspect of their families’ histories, and in the process, they make an unexpected discovery.

This novel, like my first, drew from my own family history research. A document that inspired part of the story was a deed of sale, dated 1886, that involved putting farm animals up as collateral for a twenty-dollar loan. One of my ancestors was apparently extending a loan to a Black share-cropper who lived adjacent to his farm, and who could have been a descendent of a slave family that ancestor’s grandfather had owned.

As I read the deed of sale, I wondered what their relationship might have been. The two men were roughly the same age. Had they played together as children, and had my white ancestor then learned to assume a position of dominance in relationship to this Black man, as the two grew up? How is a sense of white entitlement passed down within the family through generations? What would it mean for a white person today to interrupt passing down that sense of white entitlement?

These were questions that prompted Family History in Black and White, and Social Fictions was the perfect place to locate this novel.

The Significance of Social Fictions

Social fiction invites readers to ponder questions about the social world we inhabit, and to envision a better world and a better self who can help to create that world. Patricia Leavy’s Social Fictions series stands for more than a terrific place to publish a book, although it was that, too. The series elevated social fiction as a genre that uses both art and research to probe specific issues, and to engage readers in imagining themselves acting on those issues.

In 2021, after a decade as series creator and editor, Leavy decided to end the Social Fictions series to pursue other creative aspirations. During her tenure as editor, the ground-breaking series published 45 titles, many of which were bestsellers and award-winners. In 2014 Patricia received the American Creativity Association Special Achievement Award for her work advancing arts-based research and pioneering social fiction. The series was called “a watershed moment in the academy.” Indeed, with this series, she created a new genre and a space within the publishing industry.

The Social Fictions series was the first and remains the only series of its kind. Social fiction needs to become a widely recognized genre, especially given the deep and persistent problems that continue to plague society. Patricia Leavy has given us a gift in creating this marvelous series that names and populates this genre. For that I am deeply grateful.

References

Alcalá, K. (2007). The desert remembers my name. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Buchanan, R. & Mills, T. (2020). Using White Bread in a course for preservice teachers. In C. Sleeter, White Bread. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill|Sense.

Clair, R. P. (2021). Blood into water: A case of social justice. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill|Sense.

Gullion, J. S. (2014). October birds: A novel about pandemic, influenza, infection control, and first responders. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Lake, R. (2010). Reconstructing multicultural education through personal story. Multicultural Education, Fall, 43-47.

Leavy, P. (2011/2015). Low-Fat Love. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Leavy, P. (2016). Blue. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Leavy, P. (2020). Film. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill|Sense.

Leavy, P. (2020). Candy Floss Collection: 3 Novels. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill|Sense.

Leavy, P. (2021). Low-Fat Love: 10th Anniversary Edition. Kennebunk, ME: Paper Stars Press.

Leavy, P. (2022). Film Blue. Kennebunk, ME: Paper Stars Press.

Simon, L. & Simons, W. (2014). Heartland: A historical drama about the internment of German-Americans in the United States during World War II. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Sleeter, C. (2015). White bread. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Sleeter, C. (2021). Family history in black and white. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill|Sense.

wa Thiong’o, N. (1983). Barrel of a pen: Resistance to repression in neo-colonial Kenya. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Yunus, M. (2013, September). Create social fiction. Skoll World Forum. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4kU97gXWj0

About the Author

Christine E. Sleeter is a former classroom teacher in Seattle, Washington, and Professor Emerita in the College of Education at California State University Monterey Bay, where she was a founding faculty member. She is past President of the National Association for Multicultural Education, and past Vice President of the American Educational Research Association. She has published over 170 academic articles and 21 books on various issues related to education and racial justice and she has also published three novels, the most recent being Family History in Black and White (Brill, 2021). Awards for her work include the International Impact Book Awards, the Firebird Award for Multicultural Fiction, American Educational Research Association Social Justice in Education Award, and the Willamette University Distinguished Alumni Citation for Professional Achievement.

Credits

All images provided by Christine Sleeter and Patricia Leavy

Featured image by Katherine Hanlon for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.