Ten Powerful Poems by Albanian Poets and Their Translations

Author’s Memo

I’m Vlora Konushevci, a poet and translator from Prishtina, Kosovo. I present to you a collection of ten poems by ten esteemed Albanian poets, with a particular emphasis on the works of women poets, originating from Kosovo, Albania, and the Albanian diaspora. These poems have been meticulously translated into English by my hand.

The verses I am submitting in this collection encapsulate deeply personal narratives, effectively serving as poetic confessions. These Albanian poets have borne witness to the profound and tumultuous transitions that have defined our region, spanning the shift from communism to democracy, the liberation from an oppressive regime, and the trials of wartime and survival.

‘These Albanian poets have borne witness to the profound and tumultuous transitions that have defined our region, spanning the shift from communism to democracy, the liberation from an oppressive regime, and the trials of wartime and survival

The impetus behind my endeavour in literature translation stems from a passionate commitment to promoting Albanian Literature, a body of work that remains remarkably underrepresented on the global stage. It is worth noting that it has been over a decade since Kosovo achieved its independence, and merely two decades have passed since the cessation of the last war. I ardently believe that poets, as astute witnesses of the era they inhabit, possess a wealth of compelling stories to contribute, thus enriching the broader tapestry of contemporary world literature.

As part of my dedication to this literary mission, I have previously published two bilingual anthologies: “Magma 2021” (Albanian – English) and “Poetry without Borders” (Albanian-Serbian). My translations have garnered recognition in publications such as the “Songs of Eretz Literary Review” in the USA, the “Alternative War” anthology by B cubed press in the USA, and most recently, in “The Common,” also in the USA.

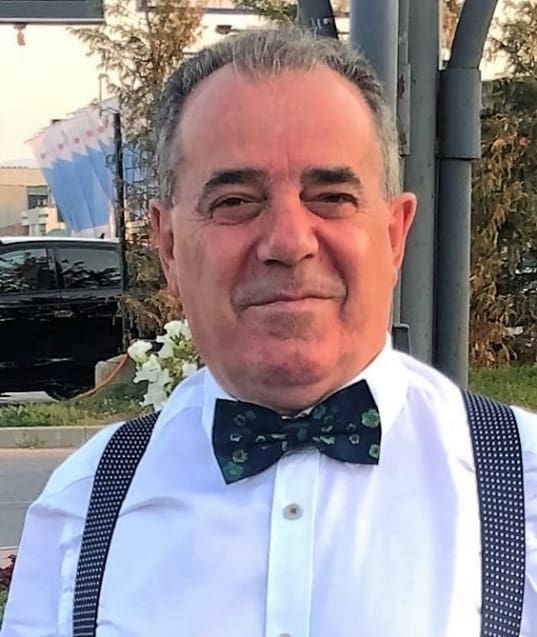

Halil Matoshi

Halil Matoshi (1961) is well-known poet and publicist of Kosovo. He graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy and Sociology at the University of Pristina. He worked as a journalist, editor, and editor in chief of magazines and newspapers as “Bota e re”, “Zëri i rinisë”, “Zëri”, “Lajm”, “Express”, “Koha Ditore”, etc. Matoshi was taken hostage during the war in Kosovo (1999) and held for a year in the Serbian Concentration Camp in Lipjan (Kosovo) and Požarevac (Serbia) He is author of the books: “Journey through bad dream” (1994), “The dumb messenger” (1996), “Journey through bad reality” (2000), “Shadow of Christ” (2004), “Cathedral’s from paper” (2012), “The Origin” (2013) and “Light engraving” (2021); His poems have been translated into German, Spanish, Serb & Croatian, Turkish, Romanian, Greek, English etc.

How easy it was to carry mother on my shoulders…

How easy it was to carry mother on my shoulders…

I’ve seen the horror weighing on her eyelashes

when she watched older women on TV

chased by the enemy

being dragged by someone on a goatskin sack or being carried like a child

on a winter day, piled up in a cart with deflated wheels…not to mention when she heard the wails over knife cut children and men

mother couldn’t even take a step without being out of breath

when I fell into the hands of the Serbian police

and got ready to be shot, she remained surprisingly silent

just as a clay statue

measured and sized up by archaeologists

guessing its age, its pulse, its resistance to crashes

and temptations of mother earth

working hard to find the beginning of its life

and to construct such a tragic death which has caused such great pain like the murder of its son, such an unbounded horror for the world history to create a literary fiction

and make an all-time drama out of it

from a simple a silent mother

I looked at her at once

only her eyes moved

enough to let me know that I left her alive

wait for me, mother, I wanted to say

but my voice abandoned me …

I still feel it even now, she tells me

I won’t die until you come back from exile

I am one hundred percent sure that she wanted to say “I won’t die”

but she put her hand over her mouth

out of fear of committing sacrilege

not to let out a single sigh of despair

she was a fantastic mother and waited for me

she saw my bloodless forehead, shook my chainless hands

I too became a patient son and waited for her white death the shroud’s charm

I saw how easy it was to carry mother on my shoulders

five grown up sons…as we exchanged to carry her

(she was so light and still it seemed as if both legs are sawing into the ground – maybe it’s the same as when she carried children in her belly, except now you’re mournful, while she was happy then, she was giving life!?)

she saw my freedom

I saw her death…

I remember in the spring dawn of May

mother was dressed solemnly

she was singing not sleeping…

and then suddenly she was silent

everything fell into place like on a stage where a ballet is played

she did all the house chores

and fell asleep…

at the end, in late autumn

she flew high up

like a butterfly dressed in the season’s white

Blessed mother

Dije Demiri Frangu

Prof.asoc. Dr. Dije Demiri-Frangu, was born in Kosovo, is a professor at the Faculty of Philology of University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina” in Prishtina, Department of Albanian Literature.

She has published 13 books of poetry for adults and children, as well as the book with studies on children’s literature: Children’s literature (genesis, phenomena, and authors), 2009, 2011, 2017 (republished and updated three times).

She has participated in various seminars and conferences with works on literature. She is a participant in the Seminar on Albanian Culture and Language for Foreigners with thematic works which are published in the Journal of the Seminar on Albanian Culture and Language for Foreigners, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 20011, 2013, 2014, 2015 , 2016,2017, in IA of Prishtina. She was also part of different symposia, and participated in Balkan Conference in Edirne. She has been the Secretary of the International Seminar on Albanian Language, Literature and Culture, for two terms. She was also a member of various juries and member of the Book Council in the Ministry of Culture of Kosovo.

Demiri Frangu is fluent in English and Serbo-Croatian language. She worked as an editor in the magazine “Rozafa” for a period of 4 years. (2000-2004). She has led the women’s association “Rozafa” for two terms ((8 years). She has worked in the association Switzerland-Kosovo for 4 years in a row. Her poems were published in various poetry anthologies in Kosovo and abroad. Her children’s book “When it rains on the sea” was translated into Swedish language – När det regnar havever havet – in 2003

Luckily war broke out that spring

Luckily war broke out that spring

I was neither young nor old

and I could look it in the eye

I had learned many fairy tales to tell to children

I drew the face of freedom in a plain notebook

I made it beautiful and they enjoyed looking at it

luckily war broke out that spring as there were flowers

to cover the grave mouths and they were many

how deeply scarred was the field

I’d bought 10 kilograms of salt,

10 kg of potatoes I could hardly carry home

I never wondered why I got so much

since then I have a twisted spine

I’d gone back to the city’s Guardian Angel church

I took candles

hoping we would cast out the dark and show freedom the way

It’s really good war broke out in March, April, May and June

Somehow the sun stayed longer in the sky

You could see the bomber planes more clearly

And not a single bullet managed to hit me

If war broke out before or after

I could have been killed by the bullet

I am convinced that I would have been killed

And long forgotten by now

Luckily war broke out that spring

And I didn’t get killed

Ardiana Shala Prishtina

Ardiana Shala Prishtina was born in 1983 in Prishtina, Kosovo. She is a psychologist, publicist/writer, researcher and feminist activist. Her literary work was published in anthologies and literary magazines in Albanian, Romanian (translated by Ardian Kyçyku), German (translated by Zuzana Finger) and English.

Margarita

Why don’t you write about love?

See how beautifully the leaves are falling in autumn.

Oh. When autumn falls it reminds me of a woman.

Her teeth fell out one by one.

And her eyes fell to the ground.

No one ever heard her complain.

No one ever saw her loneliness

which she cloaked in the winters

as she expected them vast

while she shrank in that house

as no one dear ever returned.

Frightened out of her wits

that Spring would leave her alone, again this year.

When she died, prayers were said at her grave

by unknown people who met her coffin

on the way returning from another burial.

Why don’t you write about the blue sky?

See how beautiful it looks cloudless.

Oh. The blueness of the sky reminds me of a woman.

She pulled all her hair out waiting for her son’s bones.

No one ever heard her curse.

No one ever knew her pain in winters

which she expected wrapped in a thick curtain of tears.

Frightened that Spring would come

and snatch away another hope, again this year.

In the cemetery she touches the graves

of strangers while holding her son’s sky-blue shirt

found among the remains of missing persons

for which no priest or imam could pray over its burial.

She goes to the cemetery often

like a cloud overshadowing her own feet.

Why don’t you write about freedom?

See how beautifully the flag flies.

Oh. Freedom reminds me of Margarita.

With each passing year of freedom

another skin falls from her body like the last sigh.

Ripping off, layer by layer,

the shame she feels, but isn’t hers.

No one ever heard her cry for help.

No one ever lost any sleep over her sleepless agony.

Frightened to death

that Spring shall come again this year, dark as night.

On the street, when she walks past others,

Clenching her hands firmly one into another

so that her own self may not run away

within the crowds that kiss bronze monuments

and cling like phlegm to flags.

Oh. Freedom. Margarita. Margarita. Freedom.

Margarita. Margarita. Margarita.

Margarita. A faceless monument.

A dried spit

of the unheard scream unable to loosen

the rope hanging round freedom’s neck.

Ilire Zajmi

Ilire Zajmi was born in Kosovo in 1971. She holds a PhD in Mass Communication Sciences. Author of six volumes of poetry, four published in Albanian “Këmbanat e mëngjesit”, “Baladë e bardhë”, “Valsi i mesnatës”, “Vjeshta është grua”, one in English “Amnesia” and one in French “Ce la fin ”. Author of the novels “Fashitja e ëndrrave rebele, “Era”, “Një luftë e pakryer”, the publicistics book “Un Treno per Blace” published in Italy, translated into Albanian “Një tren për Bllacë” and in Croatian “Vlak za Blace” “, as well as the study book “Television footage and reality “. Her poems have been translated in several languages and she was a part of many international literary festivals.

Identity

My ID card has a misprint

A passport to travel to few countries of the world

My homeland has two names

They call me an ethnic Albanian in a multi-ethnic society

I am ruled by a gang of villains and ignorant politics

I get my salary from the Kosovo consolidated budget

I have an account with an American bank

My father receives a 70-euro pension

My mother, a teacher, strikes more than she works

My sister fell in love with an Irishman

My brother protests in favour of a better university

My neighbours hope that their son is alive or dead somewhere in Serbia

Anna Ahmatova, tell me how I am to decode identity

I live in a city of half a million

In a Kosovo disappointed by the dream of independence

Drink cheap espresso with my friends

Write text messages and make virtual love

I live in a country of undefined political status

Where someone says there was a war

While others say it was just a conflict

Ardita Jatru

Ardita Jatru was born in Tirana, Albania in April 1972. She has published four poetry collections and one novel. In 2018, the publishing house Transcendent Zero Press (USA) published her poetry collection entitled “66 kilos of solitude”.

Her poems have been translated and published in many international literary magazines, such as in Greek, English, Romanian, French and German and are included in Albanian and international anthologies.

This year at the international poetry festival “Netët Korçare te Poezisë” in Albania she was awarded the prize “The most beautiful poem”.

She is the general secretary of the association of Albanian immigrant writers in Thessaloniki “The Green Branch”. She lives in Thessaloniki since the fall of the communist regime in 1990.

Hemicrania

Grief marches

beside me

and some illegal immigrants

running to hide.

I buy cigarettes for a Pakistani who begs me.

I light up his bitterness

my nerves are screaming.

My anxiety

raises its spear.

It waves the battle flag above my head.

My conscience burns.

My face

white

like the moon.

I stand before the psychiatrist

sleepless

I sit.

He asks me about things I don’t remember.

My memory comical.

I laugh.

We end the session.

I rise

and the black hole on the threshold swallows me

and spits me out on the street.

So, I come back to you

unconscious

like a wounded child, rejected

from the game.

Manjola Brahaj

Manjola Brahaj was born in Tropoja, Albania, in 1986. She completed her undergraduate studies in Albanian language and literature at the University of Tirana, where she earned a Master’s Degree in the Theory of Literary Criticism in 2010 and a Ph.D. in literature in 2017. She is professor of literature at UBT and “Ukshin Hoti” University in Prizren. She is the author of five books. Four books of poetry: “Vajtimi i Kalipsos” (2010), “Na nuk jena t’ktuhit” (2014) “Çka nuk tregohet nuk ka ekzistue”; “Ama nji lak” 2020 and she is the author of the book “Proza eksperimentale- Rasti i Pashkut”, (2018).

In parting

In parting, you are a well packed suitcase,

with something missing as usual.

You are thousands of instructions to be fulfilled,

you are your former self crying for you.

You are the door closing with a cold creek,

which seems to open a pit in your heart.

And you become a hand raised in the air to say goodbye,

a back turned so your tears don’t show,

even in parting you want to remain a desire.

In parting, you’re an awakening with the morning auras,

you are your sister’s hug, unbestowed

for fear of disturbing her sleep,

you are the gaze of the mother who stands and waits until you’re

no longer visible,

beyond the mountain,

you are the impossible companionship of your brother,

you are the absent presence of your father

the feel of his handshake.

In parting, you’re all your memories that shake you,

as a high forest shaking hairs of snow.

In parting, songs of silence are sung in honor of your step,

and you become a foot pressed to the earth,

leaving tracks;

in earth’s black flesh,

in your misty fate,

in the dreams of those you leave behind.

In parting you become a boat sailing to the unknown,

feeling like a migrant bird,

hurt yet fully filled with hope,

feeling surer than ever you’re not from around here,

in parting, more than anything, you’re a regret.

Nora Prekazi Hoti

Nora Prekazi Hoti, born in Mitrovica, Kosovo and graduated from the Faculty of Ethnology within the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Prishtina. She completed her MA studies in Ethnology within the Institute of Anthropology and Art Studies in Tirana, Albania. She was also a short time scholar of the Museology studies in the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the School of Design, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Mrs. Prekazi Hoti has over eleven years of work as an ethnology curator at the Museum of the City of Mitrovica, and is also the founder and leader of the Dhemetra Foundation in Mitrovica, as well as the Director of the Zana Literature Festival in Mitrovica. Nora is also a social activist and poet. She is about to publish her first book of poetry with the name “Amë” with the Publisher House LITTERA in Prishtina, Kosovo. Her poetry has been translated into English, Serbian and Greek Language.

Under the sheets

The only truth lies beneath the sheets

The only truth

when the armor is removed

shields thrown aside

the soul stripped bare

and then we see each other plain

beneath the sheets

where the holes of childhood

post-traumatic syndromes match

the scars left by our unfortunate love affairs

Because we are all relics of holes

of many cavities pulsating with the blood of identity

confronted with every kind of personal concern

Strange how the other is loved

in the whirlpool of the madness of being

but we are only true beneath the sheets

where you embrace me

your holes hug mine

and we look each other plainly in the eye.

innocent

chaste

purified of all tricks

human

we love…

Blerina Rogova Gaxha

Blerina Rogova Gaxha was born in Kosovo. She is a poet, essayist, and literary scholar; she has a Ph.D in literary sciences. Laureate of the International Prize for Literature, Crystal Vilenica Award (Slovenia, 2015), and the National Prize for the best work in poetry (2020), she has given numerous presentations at literary festivals and bookfairs in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Croatia, Slovenia, Ireland, and Macedonia, and she has been a guest writer at international writers’ residencies in Vienna, Split, and Novo Mesto. Her poems and essays have been translated and published in German, English, French, Italian, Slovenian, Croatian, Greek, Romanian, Turkish, Bosnian, and Macedonian.

Her work has been presented in the anthology of European poetry Europe Grand Tour, 2019. Gaxha’s essay “Easy Life,” written for the project Archipelago Yugoslavia of Traduk, has been translated into several languages and published in major Western media. She is a member of the Kosovo PEN Center. She has published “Gorgona” (poetry, 2009, winner of the National Prize for Poetry, 2010), “Kate” (poetry, 2013), “Forms of Kadare’s prose” (literary criticism, 2015), “She comes from the East” (poetry, 2016), “Thasë” (poetry, 2020), and “Death in modern Albanian literature” (Ndre Mjedja, Lasgush Poradeci, Mitrush Kuteli – monograph, 2021).

Married

Married people don’t talk about sex

don’t talk about madness either

married people behave kindly

as good old friends

or sworn enemies in the midst of quarrels

accreted by time

an unwritten agreement between heads of household

hatred is not spoken of however

and there is no talk of love

nor of lovemaking

much less of the solitary soul

dead dreams or boredom

married people are stones worn away by waters

but

they are there

Enkeleda Ristani

She was born in 1974 in the city of Fier Albania where she completed higher studies in the field of business administration. She has published three books of poetry: “Perënditë vishen me mjegull,” “Nesër është e vona ime” and “E di, Gyter?”.

One of us

One of us dies at the end of this story, Gyter

They save their asses as always

In the name of the law

Of the written word

The only black stain on the only white thing they have

Boxes with all the colours of our death

We must obey

To obey literally

Which means

Praying to the only God, Gyter

Death

Which at the end of the story

Understands not a word of the ritual they summon him with

Turns his head to make out the truth of the call

The lamb that belongs to him

Before him there are only words and one of us

But, Gyter, Death is the only one that keeps his word…

Vlora Ademi

Vlora Ademi was born in Prizren, Kosovo, she completed her studies at the High School of Journalism “Faik Konica” in Pristina, and earned her master’s degree at AAB College. Currently, in addition to her work as a master trainer within the education program at GIZ, she also directs the NGO Social Creativity, whose activities are mainly focused on cultural diplomacy, especially the promotion of poetry, as she is a poet herself. Her first book of verse titled “Katërdhetë e pak” (2022) was published by Onufri. Her poems have been translated into German, English and Arabian and published in several anthologies.

I will not forgive his fidelity

I will not forgive him for never cheating on me

I won’t forgive him!

As I wanted to appear merciful,

I wanted to be proud of my courage,

I wanted to see myself challenged

facing the beauty of another,

facing her schemes and charms,

facing high heels which I never liked.

I wanted to see the fear in his eyes,

submission,

attitude when confronted with the act of betrayal.

I wanted to hear him stuttering,

I wanted to see him guilty

kneeling before me, just as before Saint Mary,

as I wanted to feel as mighty as her,

as I wanted to measure my sensibility,

measure my strength

would I be able to send to hell

butterflies in my stomach,

the wedding ring with his name engraved on it

and twenty grey hairs for twenty years of marriage.

I wanted,

oh how much I wanted,

to see him coming home late

and myself just as those victims on Hollywood movies

on a burgundy robe

waiting nearby a night lamp in darkness.

I wanted to find a lipstick mark on the shirt I bought him

and measure the balance of my rage.

I wanted to look him in the eye and say:

now you’ve proven your manhood,

because where I come from

men’s manhood is measured

only to the number of women they “have had”!

Credits

Featured Image: Aerial View of City Buildings in Phristina for Pexels by Ferdi Noberda

Image of a picturesque scene of the Osum River by Vladan Raznatovic for Unsplash

Photo of a door in Berat, Known as the city of a thousand windows by Vladan Raznatovic for Unsplash

The Heroinat Memorial in Pristina Kosovo for Pexels by Şenad Kahraman

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Vlora Konushevci, poet and translator from Prishtina, Kosovo the Balkans. I translate from Albanian – English and vice vërsa Albanian poets (mostly women poets) from Kosovo and Albania and our diaspora. The poems presented here are personal narratives which can be seen as poetic confessions as Albanian poets are witnesses of challenging periods such as the transition from communism to democracy, from an oppressive system to that of being free, from the period of war to that of survival. The motive which has urged me to undertake the task of translation is the promotion of Albanian Literature which is the least known literature in the world. It’s been over a decade since Kosovo gained its independence and only two decades since the last war. After years of oppression, segregation, and war, Albanian poets have abundant and lively stories to tell hence I strongly believe they will add a valuable piece to the mosaic of modern world literature. I have published two bilingual anthologies Magma 2021 (Albanian - English) and Poetry without borders (Albanian-Serbian). My translations have been published in "Songs of Eretz Literary Review" USA; B cubed press "Alternative War" anthology USA and most recently in "The Common" USA.