Atlas Markers: An Emerging Autoethnography

Author’s Memo

Atlas Markers n is largely a thought-piece on the development of a research project that I have been working on for the past 10 years. The project is part genealogy and part social analysis. My grandma and her family and geographical history are the centerpiece of this research. This research is, as I explain in the article, an atlas of ordinary spaces. The work here includes atlas markers. These markers identify places where geographical and historical (and familial) events that shape the spaces where my grandma lived.

I am a sociologist and professor at North Dakota State University. Because of my responsibilities to my field and department, I struggled to make time for this project, which felt too personal for purely academic pursuits. It wasn’t until after my promotion to Professor that I felt free to openly pursue projects that allowed me to be more creative and personal. I wanted to write without worrying about academic boundaries and standards.

‘Atlas Markers n is largely a thought-piece on the development of a research project that I have been working on for the past 10 years.

I didn’t want to forgo good sociology, but wanted to start writing for a different audience. I wanted an audience that looked more like my family and to write in a way that was my personal voice—a voice that is first-generation college educated, a voice that is introspective, a voice that loves playing with words and ideas in unusual ways. As a result, I started writing this research as part creative non-fiction, part public sociology, and part memoir.

I have dabbled with autoethnography in my past research, and it feels like a natural approach for me. Yet, I was hesitant to use autoethnography in this project. I discuss this in the article you will read. My approach to this research was not conceived as an autoethnography, but I think it is an approach that allows me the ability to weave multiple forms of data, multiple conflicting narratives, and juxtapose seemingly unrelated experiences, events, and people together.

As I discuss in the article, trying to keep myself out of the research process became impossible. Since I have been embracing my presence in the research, I have been able write with greater clarity and confidence. I struggle a little to call what I’m doing autoethnography, feeling like a bit of a novice pulling from the method in ways that make sense to me and this research. What I am trying to do in this article is introduce my research without hiding the importance of my voice and my relationship to my grandma.

Atlas Marker #1: Charlie Trees

“What are those trees again?”

“Joshua Trees. Beautiful forces of nature.”

Justin’s eyes rolled at my clichéd expression of love for those trees. But Joshua trees are forces of nature. Stark and lonely. If you look at the horizon, you see the space between each. They rarely appear too close to one another. That space seems important to me. And it’s part of their charm.

These are desert trees. Well, technically, they are succulent plants. They are yucca plants that are tree-like in habit. Prickly green and brown. The limbs wiggle and writhe out of its ragged trunk—a sheer act of determination. Trees (and plants that are tree-like in habit) are a significant part of my storytelling. They are a significant part of the journey.

‘These are desert trees. Well, technically, they are succulent plants. They are yucca plants that are tree-like in habit.

“Supposedly the name came from Mormons crossing the Mojave Desert,” I explain. “I guess they thought the trees looked like Joshua—from the bible—praying.” I say this, unable to remember where I heard that story.

Justin looked underwhelmed. I’m sure this was further proof that I was his nerdy tree-hugging aunt. And I would soon feed further into that perception.

“Let’s stop at this rest stop, so I can get a closer look at one of those trees.”

A quick glance at the Joshua Tree reveals gnarled bushy tendrils tearing at the forever-blue sky. That beautiful blue sky that deceptively lures you into the brutal sun. It was 110 degrees that day. I was sweating and squinting, looking up at the tree.

“Supposedly the name came from Mormons crossing the Mojave Desert,” I explain. “I guess they thought the trees looked like Joshua—from the bible—praying.”

‘A quick glance at the Joshua Tree reveals gnarled bushy tendrils tearing at the forever-blue sky. That beautiful blue sky that deceptively lures you into the brutal sun.

“How much longer you gonna stand there?”

“Let me get a picture.”

This time I hear a heavy sigh, but I take my time, getting multiple angles of the tree. “Okay, I’m ready to get on the road.”

As my two nephews and I drive toward old Route 66, I’m excited to experience this route as an adult, and even more excited to experience it with my nephews. My love of long road trips across the western United States reflects a childhood filled with car rides between Missouri and California. My childhood memories are guided by movement, passing through states, counting down the mile markers, and wondering where we would land at the end of the road. I have a distinct memory of sitting in the bed of my dad’s International Scout with my sister and our dog, sweltering in the desert heat. The dog was so hot that he snarled when I tried to pet him. I was hot, too, so I understood why he was so crabby. It’s an instructive memory that gives insight into my connection with movement.

We continue to drive on Route 66, making our way through California and into Arizona. I feel like the further I try to get from wide-open skies, the more they engulf me. So, I take comfort in the sparse trees that punctuate space like nothing I’ve ever seen.

Joshua Trees. I’ve been fascinated by them for a long time. These trees, or plants, are survivors, living stoically under the most brutal of circumstances. Each newer bristly layer grows out of the slowly hardened fibers that look like bark over time. They are resilient.

‘This time I hear a heavy sigh, but I take my time, getting multiple angles of the tree. “Okay, I’m ready to get on the road.”

“Look. More Charlie Trees.” Justin snaps me out of my thoughts.

“What?”

“Over there. See all the Charlie Trees?”

I turn to see the sharply defined patterns strewn across the desert. Spikes of relief along a wide-open horizon.

“Charlie Trees?” I laugh a little, and “Charlie Trees,” nods Justin.

“Charlie Trees,” I say, nodding too. “That sounds about right.”

Starting and Stalling Along the Way

I start my story with Charlie Trees (yes, that is what I call them now) for a couple of reasons. It was on that road trip with my nephews that I decided I had to tell the story of my grandma and our family. The route we took started in the San Francisco Bay Area, moved south through the desert past the Grand Canyon, through New Mexico, then up through Colorado, and eventually back to Fargo, North Dakota.

This trip gave me my first opportunity to visit Victor, Colorado. It’s been 12 years since that trip. Twelve years that this project has been stewing and evolving beneath the surface of my life. It has been about 10 years since I first started collecting data, telling myself this is a side project. I’ve been procrastinating, working on other projects, stewing, certain about needing to tell this story, but not certain about what kind of story I should tell.

‘My atlas tells stories about ordinary spaces. It offers multiple vantage points of family and historical events.

Early on in my work, it became clear that land and geography were part of the story. I envision this project as an atlas of ordinary spaces. There are various geographical markers that take me through a journey of family and land. My atlas tells stories about ordinary spaces. It offers multiple vantage points of family and historical events. In For Space (2005), Doreen Massey conceptualizes “ordinary space” as “the space and place through which, in the negotiation of relations within multiplicities, the social is constructed” (my emphasis—pp. 13). Space, according to Massey, “is the product of interrelations” and contains “the possibility of the existence of multiplicity in the sense of contemporaneous plurality” (pp. 9). Ordinary space has many stories to tell. My goal is to convey the value in telling stories that are contradictory and/or incomplete. When looked at together, new insights can emerge.

This journey of mine is marked by missing information, misremembering, miscommunicating, and misunderstanding. Yet in the end, all those mis’s create a deeper understanding of what it means to be part of the land, part of a kinship system, and part of a family. Much like Charlie Trees, the journey looks like one thing against the desert sky, but upon closer inspection, there are beautiful and unexpected depths to discover. Its juicy richness lay hidden between twisted brambles.

‘This journey of mine is marked by missing information, misremembering, miscommunicating, and misunderstanding.

I went into this journey thinking that I would write about my family through the structures of class, race, gender, and the devastating power of the Manifest Destiny. What I realized, though, was that the richness of the story came when I started digging into the geographical spaces my family have inhabited; geographical spaces that made my life possible. Family stories tangle up with multiple histories of the land. Victor, Colorado and its surrounding geography are filled with multiple conflicting stories. It is also filled with mysteries and uncertainties that I have struggled to find in archival data. I started to understand Massey’s argument about ordinary spaces in a deeper way.

This atlas enables me to tell jagged stories of how ordinary people, ordinary white settlers, inhabited ordinary space, creating a social world that was brutal and harsh, yet was home to three generations of my family. My family, like so many others, became an important tool in the expansion of the United States. Their efforts to build a life for themselves and their families was a part of the success of the United States spreading across the continent. My family followed many others moving west. They survived numerous hardships and, oftentimes, a difficult life. But none of that was extraordinary. I say this, not to diminish my family. I say it because the ordinariness of settler colonialism is part of what makes it so powerful. And I am the legacy of that system.

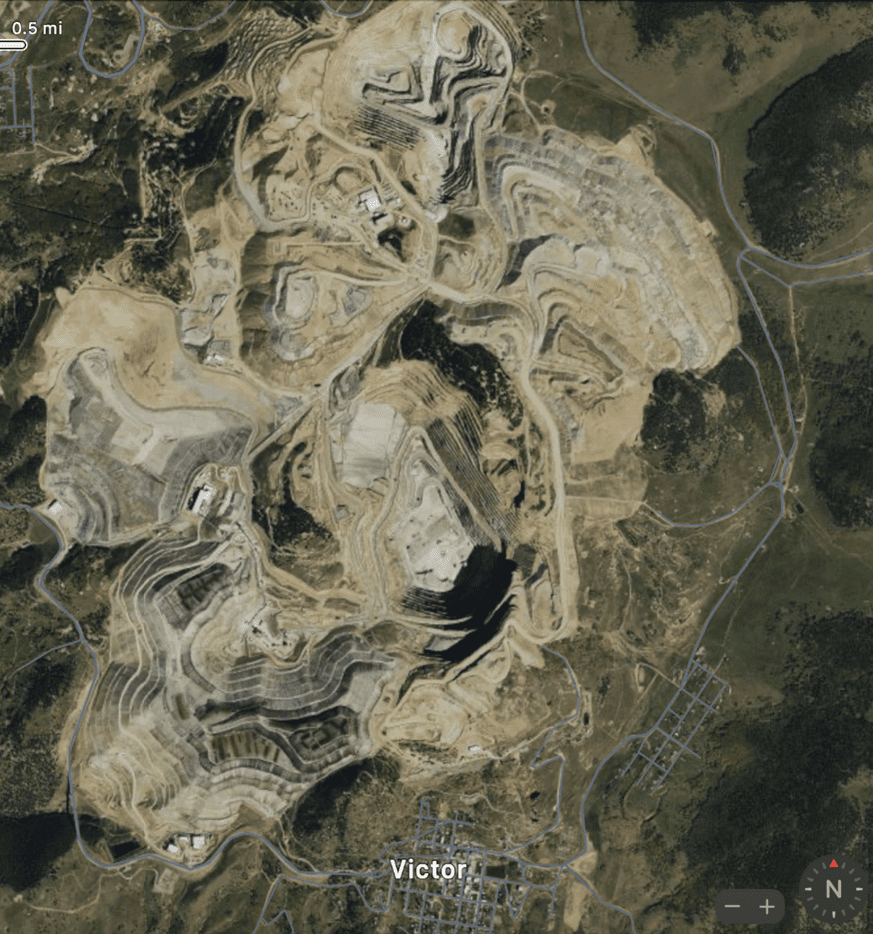

Atlas Marker #2: Battle Mountain

Victor is located on the southern base of Battle Mountain. It is known as the City of Mines, because of its proximity between living and mining. When visiting the town now, you can see the remnants of old shafts where the mining took place as you walk past modest homes on gravely roads.

In the late 1800s, gold found in the mountain brought many white settlers to the area. Victor became a quintessential mining town. My great great grandparents arrived in Victor close to when Victor became an official city in 1894. Marker #2 is Battle Mountain, the geographic centerpiece of my family’s move westward. Without Battle Mountain, there is no Victor. Without Victor, the trajectory of my family would have been altogether different. Battle Mountain holds the space where many stories collide. These are stories I’ve found in my data, but there are other stories that come from what I’ve heard in my family.

… did not envision this research as an autoethnography and I didn’t think I was part of the story.

I did not envision this research as an autoethnography. I didn’t think I was part of the story. Yet, the more research I did, the more I read, the more time I spent in archives and in Victor, Colorado, where my grandma grew up, the more I saw myself in the story. I am the one taking this journey and deciding which routes to take based on the markers I’ve found along the way. I am crafting a story of how my family is an ordinary family shaped by extraordinary events in breathtaking geographical places. And I am, after all, the legacy of that story.

The more time I spent in Victor, the harder it became to write myself out of the story. This journey is motivated by a deep need to claim a sense of home. As I’ve journeyed through the geographical landscapes of my family, the emotional tenor of my journey grew deeper, more urgent. Part of me believed that if I delved deep enough to understand my family’s connection to Victor’s history and geography, I could find a deeper connection to my grandma and by extension, a place to call home.

‘The more time I spent in Victor, the harder it became to write myself out of the story. This journey is motivated by a deep need to claim a sense of home.

Then my grandma died. Her death left me paralyzed with grief. For nearly a year, I struggled to return to the research. I would run into questions only my grandma could answer. It was a reminder that she was no longer there. I continue to grieve, but now I’ve turned to this research more and more as a way to connect with my grandma. It’s become part of my grieving process. I stopped trying to keep myself out of the analysis and writing. The more I wrote, the more I started to understand that the driving force of my research is my grandma and my relationship to (and with) her.

‘As I’ve journeyed through the geographical landscapes of my family, the emotional tenor of my journey grew deeper, more urgent.

When my nephews and I arrived in Victor, I was only thinking about how fun it would be to see where my grandma grew up. I immediately fascinated by the geography. The town was celebrating its mining days, so when we got there it felt like a town frozen in time. My previous perceptions of Victor came from pictures such as the one above. My grandma’s father, William Lehr was a photographer. He took many photos of Victor over the years and left a collection of images that help imagine the old time feel of what Victor once was. When I arrived with my nephews, I felt like the town was still trying to hold onto that era, but something unsettled me. Not in a bad way, but it left me curious, and I wanted to know more.

What I started to understand, as I looked for Battle Mountain on a satellite map after the Charlie Tree Road Trip, was that there is a tension between the narratives of Battle Mountain and mining in Victor. The quaintness that I felt in Victor and in Gold Days events stands in stark contrast to the open pit mining of Battle Mountain. One story emerges as you walk down Victor Avenue, and another rises when you look at the satellite image below.

Starting, Stalling, Starting Again

I started with Charlie Trees. The thing of confusion. The place of humor and lightheartedness. We then head to Battle Mountain, a source of tension, a space defined by numerous struggles over resources. Yet it provides understanding to the starting and stalling of this project. How do stories of contradictions and missteps come together? There is no comforting, single narrative to tell. These stories are full of fits and starts. That is the power of ordinary spaces.

Work Cited

Massey, D. (2005). For Space. Sage Publications.

Credits

Featured Image by Alex Kramarevsky for Unsplash

Joshua Tree by Explore with Joshua for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

My submission is largely a thought-piece on the development of a research project that I have been working on for the past 10 years. The project is part genealogy and part social analysis. My grandma and her family and geographical history are the centerpiece of this research. This research is, as I explain in the article, an atlas of ordinary spaces. Geography, and the historical and family events that shape the spaces where my grandma lived, is a key feature of my research.

I am a sociologist and professor at North Dakota State University. Because of my responsibilities to my field and department, I struggled to make time for this project, which felt too personal for purely academic pursuits. It wasn’t until after my promotion to Professor that I felt free to openly pursue projects that allowed me to be more creative and personal. I wanted to write without worrying about academic boundaries and standards. I didn’t want to forgo good sociology, but I wanted to start writing for a different audience. I wanted an audience that looked more like my family. I wanted to write in a way that was my personal voice—a voice that is first-generation college educated, a voice that is introspective, a voice that loves playing with words and ideas in unusual ways. As a result, I started writing this research as part creative non-fiction, part public sociology, and part memoir.

I have dabbled with autoethnography in my past research, and it feels like a natural approach for me. Yet, I was hesitant to use autoethnography in this project. I discuss this in the article you will read. My approach to this research was not conceived as an autoethnography, but I think it is an approach that allows me the ability to weave multiple forms of data, multiple conflicting narratives, and juxtapose seemingly unrelated experiences, events, and people together. As I discuss in the article, trying to keep myself out of the research process became impossible. Since I have been embracing my presence in the research, I have been able write with greater clarity and confidence. I struggle a little to call what I’m doing autoethnography, feeling like a bit of a novice pulling from the method in ways that make sense to me and this research. What I am trying to do in this article is introduce my research without hiding the importance of my voice and my relationship to my grandma.