Autoethnographic Nonfiction: Grieving, or How to Make the Best Spinach Lasagna

Author’s Memo

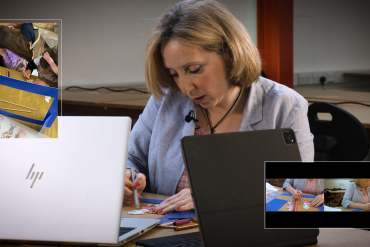

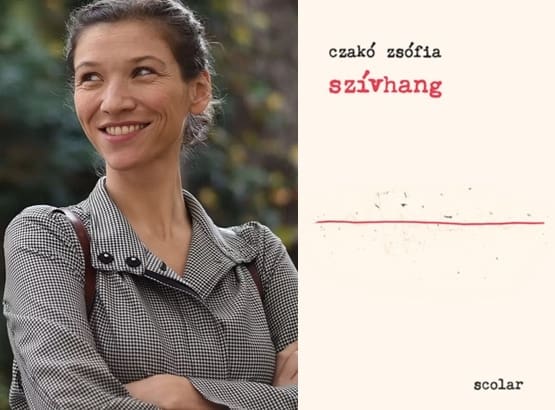

Written introspection is a way of interpreting myself and the world around me. This is a method I use to explore personal experiences within the context of cultural and societal milieus. My second book, Heartsound, illustrates this since it evolved from the circumstances surrounding my own miscarriage. It allowed me to share my autoethnographic observations of how women of different social strata experience miscarriage and abortion.

“Spinach Lasagna” is drawn from my earlier book, It is Not Proper to Garden on Good Friday. It is also autoethnographic in that it is based on my own life and follows two story lines. The first describes growing up in Hungary in the shadow of a rigid Roman Catholic grandfather. Even when he becomes feeble in old age, he tries to dominate the whole family. A child faced with the dogmas of religion cannot view them as metaphors. They internalize them to the point that they carry over into adult life and dominate later actions.

In the second, “Spinach Lasagna”, the narrator as a young adult finds herself in a totally different culture. She works as a cashier in the famous Milan cathedral. From her booth, she observes people from many countries who come to this splendid church. There are visitors who are there as tourists, worshipers who come to pray, vendors and buskers.

Through her Italian boyfriend she becomes a member of a family of southern Italians. They see the world in a way that is completely alien to what she herself had experienced. In “Spinach Lasagna” the narrator and the writer confront and analyze the two; they become autoethnographers.

Spinach Lasagna by Zsófia Czakó

(Translated from Hungarian by Burgess & Morry)

Note: “Spinach Lasagna” is from a set of linked stories. The narrator is a young woman from a small town in Hungary. She is now working in Milan at the cathedral and living with her Italian boyfriend .

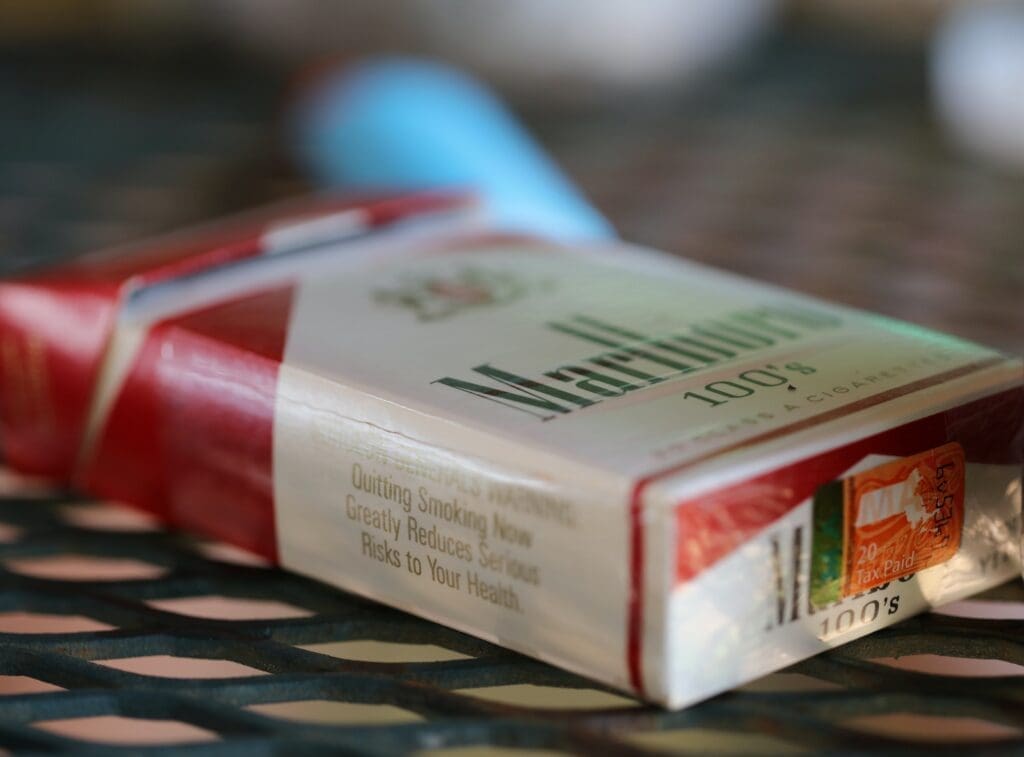

Uncle Paulo fell ill suddenly and quickly departed from this earth. At the beginning of the summer, he still asked me to bring him three cartons of red Marlboros when I went to Hungary for a few days. By the end of August, however, Aunt Rosaria needed to put one fewer plate on the table for the family gatherings.

The day the results of the biopsy arrived, he was smoking and having wine on the balcony. With surprising cheerfulness, almost smiling, all he said was é arrivato, it’s here. His physician was right, his guess was correct, the lab result was positive, he has a terminal illness. You cannot cause yourself so much harm without being punished, Uncle Paulo said. And it seemed that he wasn’t at all frightened. He wasn’t shocked by the news as if he had always smoked and drank wine with this knowledge. As if the red Marlboros had served as the most natural, most needed vehicle for attaining the sacred goal. As if each cigarette had been a sacrifice at the altar of throat cancer.

And after having opened the envelope, Uncle Paulo lit another one right away there on the balcony. He leaned back on his chair and I thought of Grandpa’s neighbor whom we called Uncle Jóska. The forever complaining Uncle Jóska had a hole in his neck that he covered while smoking. Otherwise, the smoke from his body would have gone out through that hole. I feared that the same thing would happen to Uncle Paulo.

This fear turned out to be baseless. After a few months, Uncle Paulo did not live at home any more. His condition deteriorated rapidly. We visited him only once before he ended up in the hospital. Even at the time, it wasn’t he who opened the door. It wasn’t the Uncle Paulo who asked me to bring three cartons of cigarettes. It wasn’t the sweet old gentleman who always gallantly complimented me. Instead of the smiling Uncle Paulo with a determined gait, someone else was standing at the door.

Here was a surprised stranger with bulging eyes. He shuffled slowly past the sofa and sat down with difficulty in the leather armchair. He wasn’t able to rise again as long as we stayed there. The hole, the sight of which I dreaded, was covered by a small piece of gauze. My boyfriend didn’t like it at all when I asked him whether Uncle Paulo would smoke the way Uncle Jóska did after the tracheotomy. He said he had never seen anyone who would smoke after a tracheotomy.

My boyfriend had been preparing a banana puree in the kitchen when he said that I must have dreamed the whole thing. Uncle Paolo could only eat mushy things and drink filtered water after the operation. The uncle in the form of a stranger, or the stranger in the form of the uncle, was sitting in the living room. Though attentive, he was somewhat frightened. He couldn’t talk; he had lost his voice. I wished that I had lost mine, too. I didn’t know what to say to Uncle Paulo.

Just a few weeks ago he was laughing heartily on the balcony while telling a political joke. His head was thrown back as his dentures shone in the sunlight. And now he was sitting in an armchair in the living room. His neck had grown twice its normal size. His eyes were bulging, his mouth drooping, and his back humped. And his fingers linked together on his chest and he didn’t say anything. He didn’t expect anything. He just stared directly in front of him with curiosity, like a stranger.

I kept counting the seconds until my boyfriend would get back from the kitchen with the banana puree. He would feed it to his uncle and wipe the corner of his mouth. Then he would pat his head, arm, and knee, exactly the way he always did, with the usual kindness and attention. It was something we could always count on.

It snows in the winter and it is cold. We sweat in the summer and it is warm. Uncle Paulo got throat cancer. These are facts that cannot be changed, facts which my boyfriend, just like his family, accepted without drama.

After we left, all he said in the car was povero zio Paulo. Poor Uncle Paulo. I knew that he wouldn’t start crying; he wouldn’t break down. He received the not-so-surprising but inevitable natural fact that Uncle Paulo had throat cancer with almost cheerfulness. It snows in the winter and it is cold. We sweat in the summer and it is warm. Uncle Paulo got throat cancer. These are facts that cannot be changed, facts which my boyfriend, just like his family, accepted without drama.

As I was sitting in the car on our way home, I thought of Uncle Jóska’s wife who used to come to the fence and wail and cry all day long to my grandma. And I thought of Uncle Jóska whom I only visited once. After that, I was not allowed to go over. They didn’t want me to see him as an invalid. I could only see him, or rather, his body lying in the coffin at the funeral. That is what his wife, grandpa, grandma and Uncle Jóska himself had wanted. And I had to say good-bye to him at the funeral, quietly mourning and in tears.

I remember well that first and last visit. I remember the smoking hole in Uncle’s neck. And I remember his watery eyes, and the dark kitchen with the sharp sound of his wife’s sobbing and wailing. When we visited Uncle Paulo, I behaved the way I had learned to during that one visit at Uncle Jóska’s. I had been mournful, broken down and frightened because Uncle frightened me to death. But as a six year old, I didn’t want to show my fear.

I moved closer to Uncle Jóska, seemingly courageously. But my knees trembled and I kept a safe distance of a couple of meters. I was smiling weakly as if nothing had happened. As if we were spending a pleasant sunny afternoon somewhere in a park near the playground. I looked at Uncle Paulo somewhat the same way while my boyfriend was preparing the banana puree. I forced myself to have warmth in my look. Then I shut my eyes for a second and when I opened them again I looked at him with a bright expression as one would look at an innocent, helpless child.

I tried to sneak as much happiness as possible into that look. I wanted to convey to Uncle Paulo that everything would be all right. What is happening to you is natural, painless, familiar and as it should be. And I’m a fantastic woman who never would leave your nephew. You don’t need to worry at all.

A few weeks later Uncle Paulo was taken to a hospital. Aunt Rosaria’s days were organized around the death watch of her widowed brother-in-law. She had been living alone for years since she had lost her husband to a lingering illness while young. She had lost her sister, Uncle Paulo’s wife, the same way. The strong and hardy Aunt Rosaria was trained by life while still young to be an experienced, devoted care-giver. Her early and late mornings and her afternoons were spent at the hospital. If I happened to find her at home wearing her black dress, I could be sure that she had just arrived from or was getting ready to go to the hospital.

During the last months of Uncle Paulo’s decline, she started to drag her feet, her back became bent and I could see her early in the morning as she moved with tired steps toward the tram stop, hunched over, as if she was leaving for work, dutiful, disciplined. In the evening after dark, she returned even more wasted away. She rang the bell before recounting loudly and with enthusiasm what happened to the catheter. She reported who died that day in the same ward, in the neighboring room and on the neighboring bed.

Because several had died in the ward, often young people, Aunt Rosaria told me that I shouldn’t smoke. That is what did Uncle Paulo in, those red Marlboros. And then she started crying about a woman whose thirty year old fiancé died. But then she swiftly changed the topic and started talking about the TV serials. Or she discussed the dinner. Or the necklace she made that day out of black stones, while sitting by the sickbed. And suddenly death moved far away. As fast as it had entered through the door, it flew out the window. The air became less heavy, the room lighter, the dead now living. Aunt Rosaria seemed younger.

I dreaded the thought of the hospital ward — the sickness, the death, the smells, the dying. These were completely unknown concepts to me. How was I supposed to behave at the side of the dying?

But before leaving, she confronted me at the door. When would I at last go to the hospital for a visit, she wondered. When would I accompany my boyfriend? Both he and his uncle deserve it. And I promised to go. The next day after finishing work, I started in the direction of the hospital.

Sitting in the tram I thought of Uncle Jóska’s dark and smelly kitchen. I dreaded the thought of the hospital ward — the sickness, the death, the smells, the dying. These were completely unknown concepts to me. How was I supposed to behave at the side of the dying? On the tram on the way to the hospital I drew a black curtain around myself. By the time I got off, I was exuding mourning, compassion, silence and tranquility.

When I entered the room of the dying Uncle Paulo, I could be solemn and sympathetic in exalted sadness and silence. That is how I approached the reception and asked for the room of Uncle Paulo, a patient with throat cancer. I climbed the stairs to the ward on the second floor in a dignified manner. Then I opened the door with determination. I was ready to hug Aunt Rosaria and cry to join in everyone’s sorrow.

When I opened the door I thought that it was the wrong room. First I saw the familiar red hair of Uncle Paulo’s son. Then I recognized the tone of Aunt Rosaria’s loud chatting and my boyfriend’s laughter. I saw Uncle Paulo’s emaciated body with the catheters and his swollen face. This was not the room where the dying were cried over. Aunt Rosaria stood beside the beeping machine over Uncle Paulo’s head. She was explaining why you had to put pine nuts in spinach lasagna.

Aunt Francesca, the relative from Sicily, was the first to notice me. She jumped up from her chair and greeted me with loud cheerful kisses. Someone else pushed a glass of almond milk in my hand. The room was full of relatives and friends who greeted me cheerfully and with affection. It was as if we had run into each other at a birthday party. They were asking how I was and saying how good it was to see me. My boyfriend was also glad I had come.

When Uncle Paulo suddenly began rasping and lifted his head a bit, the relatives all sat back on their chairs. Aunt Francesca went over to the patient, bent down and clasped her brother-in-law’s emaciated hand. It had been grasping at the air. She firmly held Uncle Paulo’s elbow and squeezed his fingers around her own elbow with her other hand. She leaned over to his ear, patted the uncle’s head and whispered, “I’m here Paulo, I’m here with you.” As long as Paulo’s body was tortured by a painful spasm, she stood above him. She squeezed his arm and whispered into his ear. She only let go of him slowly and gently when the pain had subsided. At that point, Aunt Francesca rearranged the pillows. She gave Uncle Paulo a peck on his grey lifeless face. And then she declared that pine nuts in lasagna are absolutely impossible.

She doesn’t like pine nuts; they give her the runs. Besides, Aunt Rosaria puts pine nuts in everything and it’s really unnecessary in lasagna. Aunt Rosaria replied that the lasagna Aunt Francesca makes could be used to kill someone. She then knocked on her own forehead to indicate that Aunt Francesca’s lasagna was as hard as stone. At that, the whole company, including Aunt Francesca, burst out laughing.

Relatives would sometimes leave the pleasant atmosphere of the orange- and coffee-scented room to be replaced by someone else. The recipe would change and the people would change. The only thing that was constant was Uncle Paulo’s pain. Whenever his body was seized by a painful cramp, another relative would take Aunt Francesca’s place. There was always someone else who could ease the pain of the dying man. Someone else would call him by pet names, caress his cheeks, and reassure him that they were here with him. He didn’t need to be afraid.

They squeezed his hands and sat beside his bed. All the while, they discussed what had happened at work, cars, children or recipes. I was sitting on a chair in a corner, thinking of hospital rooms I never saw. I thought of my deceased relatives who I didn’t know, whose illness and departure were distant, sad and mournful. There was no life, no school, no children, no lasagna recipes, no me. There was only silence, cold solitude and the unknown empty frightening death.

Read this story and memo in its original Hungarian: CLICK ME

About the Translators

Marietta Morry and Walter Burgess, are both Canadian and translate contemporary fiction from Hungarian. In addition to “It is not Proper to Garden on Good Friday” by Zsófia Czakó, from which “Spinach Lasagna” is taken, they have translated works by Gábor T. Szántó, Péter Moesko, Anita Harag and András Pungor. Many of their translated stories and novel excerpts by these authors have appeared in magazines in North America.

Credits

Illustration of Milan Cathedral by Mister Pittinger from Pixabay;

Photo of Marlboro cigarettes by David Trinks for Unsplash;

Image of tracheotomy by Davie Bicker from Pixabay

Photo of lasagna by Veganamente Rakel S.I. from Pixabay I The AutoEthnographer

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work? Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.