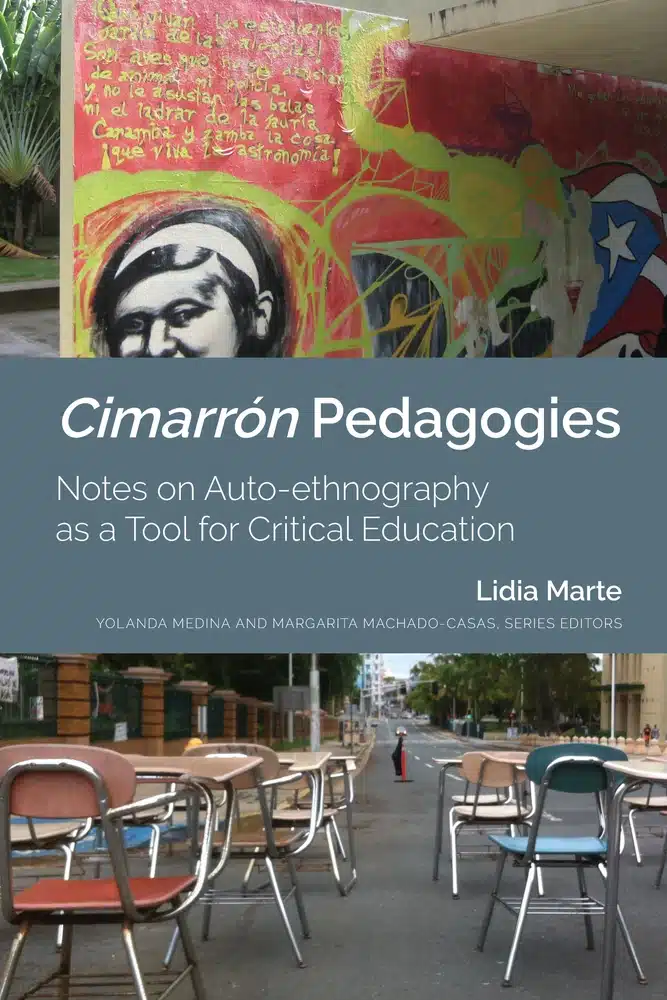

Book Review: Cimarrón Pedagogies, Notes on Auto-ethnography as a Tool for Critical Education by Lidia Marte

Cimarrón Pedagogies

Book Review: Cimarrón Pedagogies by Lidia Marte

Teaching is, or should be, about liberation. No liberation is possible without a critical engagement of one’s own life conditions. Teachers therefore must remain attentive to the socio-cultural and political context that shapes their students’ lives. The college classroom should be a space where students can examine who they are. The world that forms around students of color in particular will not simply make room for them. These students must develop the intellectual tools to envision and bring forth a new world.

These could be considered some of the founding principles—and starting points—of Lidia Marte’s insightful and inspiring Cimarrón Pedagogies (2020), part of the Critical Studies of Latinxs in the Americas series. An anthropologist, Marte draws on her decade-plus experience teaching undergraduate students in Texas, New York, and Puerto Rico. A feminist and critical race scholar, the author turns to the figure of the cimarrón, or maroon, to design courses around autoethnography as research and writing practice, with the purpose, yes, of giving students a primer on the core tenets of social science inquiry, but also, as a radical and radicalizing passageway for a sustained critical engagement with the social conditions that shape their lives. Marte explains:

I envision a cimarrón pedagogy inspired in the long-term struggles, creative resistance, and legacies of Afro-diasporic communities in the Caribbean and Afro-Latin America more broadly. This kind of pedagogy takes cimarronaje (marronage), consistent liberation strategies developed under colonial regimes, as a metaphoric narrative that goes beyond a historical moment, and that has implications for education.

Reading Cimarrón Pedagogies makes the reader want to be in the author’s classroom. Marte is particularly good at arriving at the precise terminology to make what could be hard-to-grasp concepts crystal clear. To the question of what is autoethnography, for example, she answers: “A very radical and powerful form of selfie.” She then tells students to go out and ‘hang out’ with themselves to better understand how society shapes them. In this way, the author appears in these pages as the sort of professor we were all oh so fortunate to have. The one we remember. Or the one we always wished we had.

I would recommend the book for both faculty and students. For faculty, it is a good reminder, of the originating concerns and motivations that kept us close to the teaching and learning experience. For students, it makes social science research an accessible, quotidian activity. But more importantly, it tells them that the course and classroom must be a welcoming space for them in all their complexity. Marte writes:

Rather than discarding previous experience and cultural knowledge, a critical pedagogy creates space to first discover what kinds of filters students bring to class, to identify, evaluate, integrate, and help transcend—through radical imagination—existing limitations, gaps and boundaries, according to the students’ abilities, interests and life projects.

The only sticking point—at least for me—is that though the book is informed by Afro-diasporic intellectual traditions and though much of the teaching experience the book draws from took place in Puerto Rico, it’s perplexing how little, if any, engagement there is with the small-ish, but existent, corpus of autoethnographic writing in Puerto Rico. (I’m thinking here, for example, of the work of Rima Brusi, Barbara Abadía Rexach, and Roxanna Domenech, among others). One is left wondering: what local authors are doing this sort of work within and outside academia? What are most salient issues or themes in their writing? Does their writing make it into the course syllabus?

But this, I must admit, is nitpicking. The principal takeaway of Marte’s work is the high level of regard for students that informs her pedagogy. Additionally, Marte explores how that regard translates into a teaching practice that is attentive to what her students need to navigate college, sure, but more importantly, to have a dignified life. In this sense, though this is a work that is very much tied to a specific place, its beauty and brilliance is due to the fact that this sort of pedagogy can take place anywhere.

Featured image of classroom by Stefano Ferrario from Pixabay

Guillermo Rebollo Gil (San Juan, 1979) is a writer, sociologist, translator, and attorney. He is the author of Writing Puerto Rico: Our Decolonial Moment (2018) and Whiteness in Puerto Rico: Translation at a Loss (2023). Es el papá de Lucas Imar y Elián Iré.