How to Get Lost In Xenophobia and Homophobia

AUTHOR’S MEMO

Nothing prepared me for the xenophobia and homophobia I would encounter in Italy. No one warned me how to avoid becoming their victim. Not the State Department, not the travel agency. Not the travel guides.

I vacationed in Italy in 1998 and 2010. Naïve, I assumed that San Francisco’s gay Castro district extended across the globe to Italy. So many LGBTQ+ people traveled there. Italy served as our playground, our Disney World. As a Black gay man, I assumed that my travel experiences would be identical to those of white tourists. I also assumed that my experiences would be identical to those of straight Black men.

I soon learned that my queerness and blackness intersected in unpredictable ways abroad and had to learn fast in real time because my life depended on it. Protesting, “I’m an American,” will not save me. Declaring, “I’m a tourist,” will not save me. Saying “Parlo poco Italiano” will not save me. I had to use smarts, caution, and dumb luck I didn’t learn in my Italian language tapes before my trips. How do I paraphrase Dorothy? “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Oz anymore.”

How to Get Lost In Xenophobia and Homophobia

Traveling while Black and queer in Italy presented challenges. Not the usual—my partner, Rob, and I explained to the concierge at each hotel that we wanted a room with one king-size bed. Instead, they gave us separate twin beds. We pushed them together before that night’s lovemaking. The maids pushed them apart in the morning.

But this challenge: Italians viewed my white partner as a tourist. But they mistook me for a clandestini—an illegal African migrant. As I wrote in my diary, “I learned a lot about how Italian society treated Africans by the way Italians treated me.”

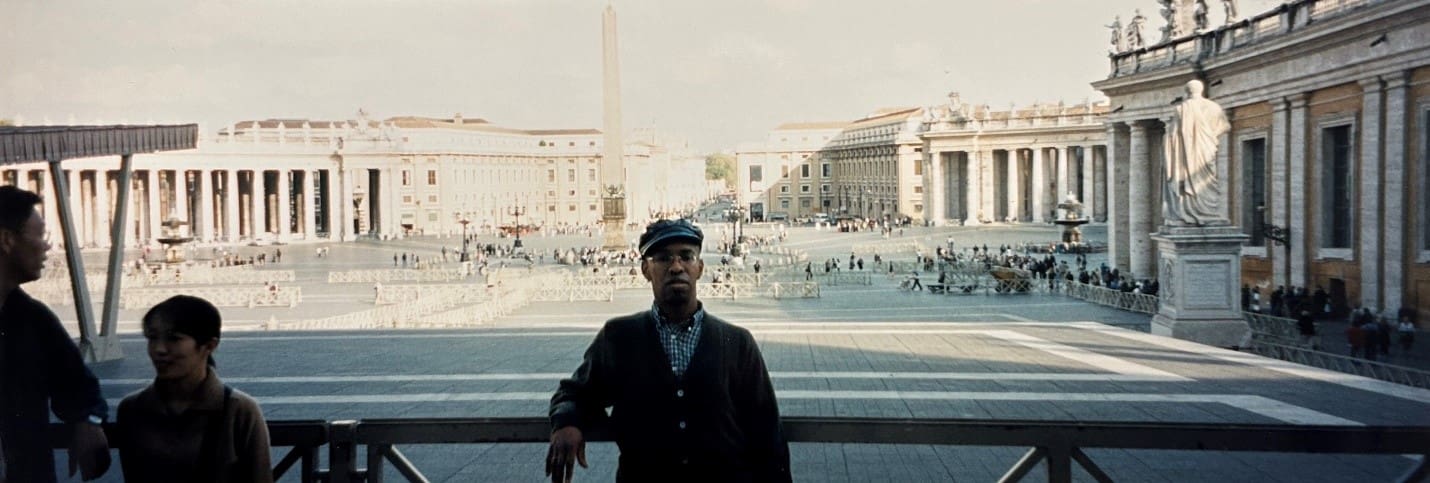

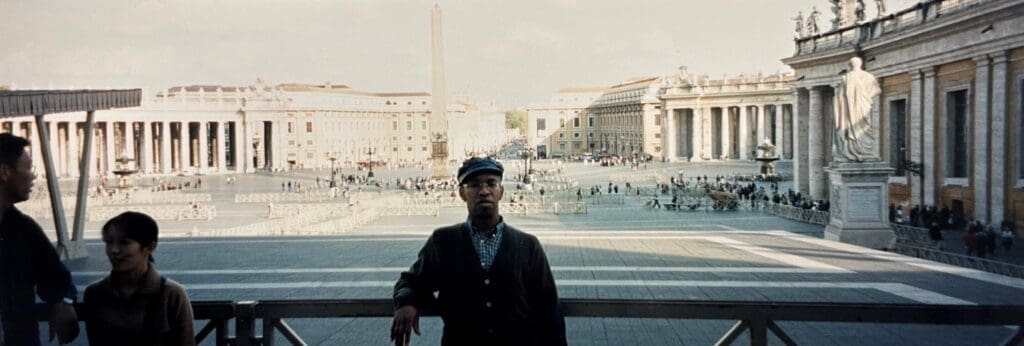

Once, I went to the Sistine Chapel with Rob’s sister, Kris. Security turned me away because of the three-inch Swiss Army knife on my belt. I had already seen the Sistine on an earlier trip. So, I sat on the stepped platform of the Egyptian obelisk in the center of St. Peter’s Square. From this vantage point, I could see Kris when she finished her tour.

Within moments, the crowds parted before the advance of a polizia car, which raced toward me. Its lights flashed. Two gendarmes with guns jumped from their vehicle and gave me orders. I could not translate their rapid Italian. But I understood what they commanded. I stood and stepped away from the obelisk. Their car retreated through the crowds.

That evening, I wrote in my diary that the police shooed me away from sitting on the steps “as if I were a pigeon.” In hindsight, the police treated me worse than a pigeon. Because police don’t shoo pigeons from monuments, but they do Blacks. In Italy, people viewed African migrants as the new vermin.

‘Throughout my visits to Italy, Italians denied me goods or services they gave Rob. I came to expect that. I did not expect lighter-skinned migrants to do the same.

At a farmers market in a piazza, I once tried buying a scarf from an Asian woman. She likely migrated from China or the Philippines. She sat on the ground with her wares—knockoff designer silk scarves—lined up on a blanket. But when she saw my black face approach, she flipped a corner of her blanket to cover her goods. With a stern look and a slight shake of her head, she signaled, Closed for business.

Oh, she must think I’m a thieving African with no money.

I had Euros in my wallet; she had scarves under her blanket.

Money might have driven her prejudice. Department stores in the Jim Crow South prohibited Blacks from trying on clothes. On a sidewalk in Italy that day, a street vendor feared my black hands would “contaminate” her scarves. She treated me as if I had pox.

But when my white partner, Rob, approached, she turned to him and uncovered her wares. Slack-jawed, I watched as she tried selling him the same scarves she had denied me. She did not realize we were an interracial gay couple or care.

Throughout my visits to Italy, Italians denied me goods or services they gave Rob. I came to expect that. I did not expect lighter-skinned migrants to do the same. First, they adopted the racism of the dominant culture. Second, they hurled it at a darker-skinned person who appeared African. Third, they affirmed my status as the lowest of the lows in Italian society. In sum, they gave me a glimpse into the racism African migrants experience in Italy daily.

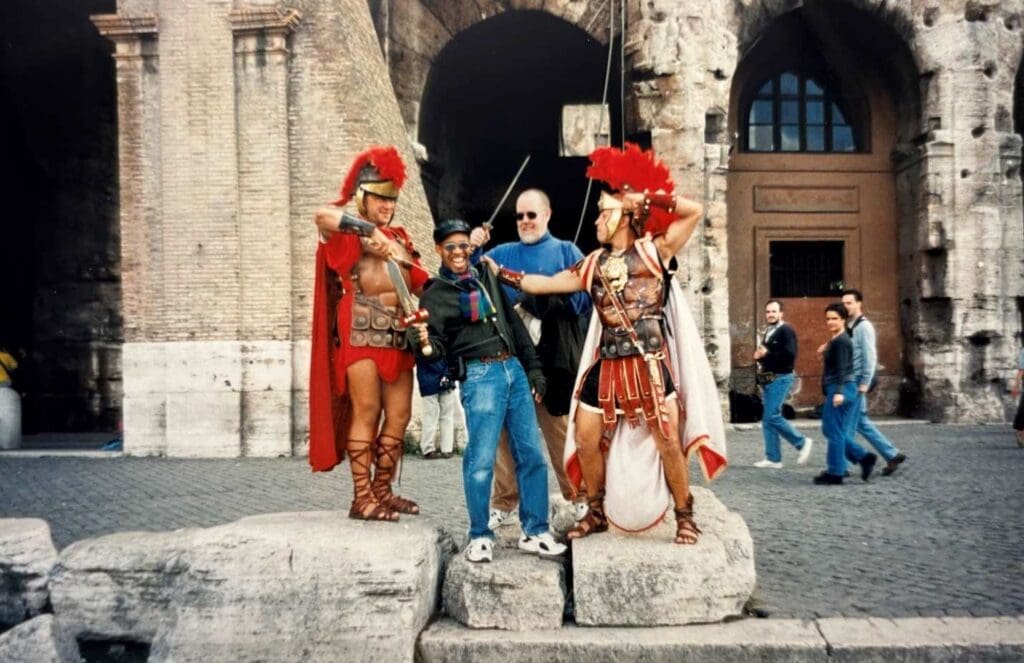

‘The centurions and Rob pretended to stab and punch me. Smiling, I defended Ethiopia. The three white men appeared to be attacking an African migrant.

Vaniglia. At a Walks of Rome night tour, our guide noticed my Black presence in our white group. As we passed the Mamertine Prison, he said, “The Romans once imprisoned one of your African kings here. He had defied Rome. So, the Romans captured and paraded him through the streets in chains. When people passed this cell, they used to hear him curse.” Later, I learned that the African king was Jugurtha (a Berber) of Numidia. Our guide gloated over his torture. This is what happens to Africans who defy Rome. After the tour, I tipped him for the insult.

Ciliegia. In front of the Colosseum, Rob and I saw two men costumed as Roman centurions. They wore armor, capes, sandals, and plumed helmets. We recognized each other as finocchio—gay. We were from San Francisco. They dreamed of visiting. “Can we take our picture with you?” I asked. They agreed for a fee. I loaned a pedestrian my camera. The centurions loaned broadswords to us. Grinning or grimacing, we posed atop large stones. The centurions and Rob pretended to stab and punch me. Smiling, I defended Ethiopia. The three white men appeared to be attacking an African migrant.

‘Some Italians and Africans assumed Rob was an American sex tourist. But they saw me as an African hustler, a gigolo nero.

While we vacationed in Italy, Italians and Africans focused on our racial differences. But I saw the questioning looks on their faces. They tried to comprehend the nature of our relationship. They paused, held their breaths, and scanned us to absorb as much information as possible. Are they friends? Is the white man a tourist and the Black man a guide? Their reading of us only lasted a second or two, but it was there.

Often I was the only Black person inside La Scala Opera House in Milan or the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Outside these venues, African migrants sold trinkets and posters in the piazzas. They looked at me, hoping I would buy from them because of our shared skinship. I also sensed their curiosity at a rarity—a Black tourist in Italy. I lived a life they could only dream.

One evening, Rob and I ate pastries at Antico Bar La Lizza in Siena. Two young African men across the cafe stared at me during our dessert. Not once did they pick up their forks. They pretended not to listen. The “Other” of Italy othered me. They saw me as Black-not-Black-like-them.

I gathered that many Africans did not have Italians as close friends, and vice versa. They exist in segregated spheres. A white man and a Black man eating together is a sight many have seldom seen in Italy.

But I felt this vibe. Some Italians and Africans assumed Rob was an American sex tourist. But they saw me as an African hustler, a gigolo nero. They wondered who did what to whom in bed and imagined how much money exchanged hands. We laughed at their assumptions and exaggerated our manners to annoy them. But once they realized we were both Americans, they tolerated our relationship. Almost.

‘Running along the walls of Siena, I realized that Italians had built them to keep out people like me.

One night, we stayed in a student apartment in the Tuscan town of Siena. Too tired from travel, Rob and his sister Kris remained inside. But I volunteered to get us food from the nearby Osteria Babazuf and walked out the door without a map.

The dark narrow streets turned me in the opposite direction I needed to go. Instead of walking uphill toward Piazza del Campo, I walked down. I recognized neither the streets nor my location.

Soon, I arrived outside the ancient walls of Siena. I did not know where or how. The walls stood fifty feet high and twenty feet thick. Panicked, I ran along the wall, searching for a gate back into the city.

Running along the walls of Siena, I realized that Italians had built them to keep out people like me. The Carthaginian general Hannibal had his battle elephants. The Saracens had their raids. And the Moors had their scimitars. For the past several decades, it appeared that Italy’s walls failed it. A thousand migrants from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia arrive on their shores daily. But that night, the walls served their original purpose of keeping foreigners out.

As a Black man in a foreign land, I knew not to ask Italians for directions at night. They might mistake me for a robber or a rapist and attack me.

Cars drove through an entrance into the walled city. I followed. Whenever people clustered on one side of the street, I scurried along the other.

The medieval skyline opened to Il Campo—the scallop-shaped piazza in the heart of Siena. Now that I knew my location, I could find the restaurant two blocks from our apartment.

That was the last night I walked alone in Italy.

As an African American, I imagine racists lynching me in my country. I never imagined strangers lynching me while I vacationed in another country.

Once, Rob left me on the station platform at Pisa Centrale to wait for the train while he went inside to buy tickets. We had seen the Leaning Tower of Pisa earlier that day and had to travel back to our hotel in Florence. On the platform, a group of young Italian men glared and cursed at me. Their faces contorted into Venetian masks. Their rapid Italian struck me like bullets. I didn’t understand a word they said because I couldn’t speak Italian well, but I felt what they said: Go back to Africa!

I knew they were shouting at me, and I ignored them, but they increased the volume of their verbal attack. The longer I remained on the platform, the closer their talk came to action. I feared they would throw me onto the tracks if I stayed at the station longer.

Rob returned with the tickets. When the pack discovered we were an interracial gay couple, they howled. Their fists gesticulated like the heads of the Hydra. The men egged each other on to strike the first blow and began to move toward us.

As an African American, I imagine racists lynching me in my country. I never imagined strangers lynching me while I vacationed in another country.

The train arrived. Its doors opened. I yelled to Rob, “Get on the train! Get on the train!”

We ran onto the train. The doors closed on our pursuers. I hyperventilated and spoke gibberish. Staring at the door at the end of the car, I feared the men would burst through to finish what they had started.

By race and sexual orientation, I belonged to two demographics most at risk of hate crimes in Italy.

‘It is no coincidence that gendarmes drove me from sitting at the obelisk in front of St. Peter’s Basilica. They have the blessing of Church and State.

Queerness is the othering of the otherness of blackness. Queerness amplifies my difference as a Black man. I never knew if people reacted to my blackness, my queerness, or a mixture. My queerness and blackness interacted in a Catholic country that was becoming more xenophobic and homophobic:

- 2018, Luca Traini injured six African migrants in a drive-by shooting spree.

- 2021, Jean Moreno assaulted a gay couple for kissing at a Rome metro station.

- 2021, the Vatican urged the Italian senate to kill a hate crime bill.

- 2022, Filippo Ferlazzo killed the African migrant Alika Ogorchukwu in broad daylight.

- 2022, Italy elected the far-right leader Georgia Meloni as premier.

It is no coincidence that gendarmes drove me from sitting at the obelisk in front of St. Peter’s Basilica. They have the blessing of Church and State.

Sometimes I find myself scrolling through pictures of Italian train stations. Rome, Milan, Florence. All stations I have visited. All are too grand.

My eyes settle on Pisa Centrale. I look not at the arches in front of the station but the platforms behind. Nausea swept over me and sank into the pit of my stomach. I wanted to throw up. I scan the corners of the pictures as if what I fear is beyond the periphery.

Suddenly, I find myself in the picture, on the platform at dusk. The men are there, too, snarling like Cerberus guarding the gates of Hades. The men are the same age as when I last saw them. I’m an old man unable to run as fast. This time, Rob isn’t with me. This time, a train isn’t waiting for me. I hear a roar, and it’s coming from the men. This time they will finish what they had started.

Credits

Featured photo and in-text photo by the author

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

André Le Mont Wilson is a Black queer writer who won the 2022 Newfound Prose Prize for his essay chapbook, Hauntings, a collection of published essays exploring the intersectionality between lynching and the Black Lives Matter movement. His essays have appeared in Sun Magazine, Litro Magazine, RFD Magazine, Sparkle & Blink, and Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora. He teaches storytelling to adults with disabilities in Oakland.