Expressions of Care: How to Provide Grief Support

Grieving in fast-paced, happiness-obsessed, and productivity-prizing cultures is tough. Taking the time to sit with your complex feelings, learning to express them for yourself, and to a supportive other requires dedicated effort. Through our collaborative autoethnography, we learned that intentionally grieving is well worth the effort. We (professor and student) created a semester-long research project that included designing and engaging in five, hour-long grief writing, art, and dialogue workshops. The designs for each of our “Expressions of Care” workshops are linked within our article. We’ve also provided secondary resources and example community guidelines to help inform these workshops. In the article that follows, we reflect on the process of sharing our grief in a collaboratively created peer grief support space. We share ten lessons learned in the process. And we encourage other groups–from book clubs to affinity circles inside prisons–to express care for themselves, their lost loved ones, and one another.

“We tell stories to keep our souls intact when suffering overtakes us.”–Mark Yaconelli, Between the Listening and the Telling

Sunlight streamed through yellow leaves, scattering spots around us on the floor. We, Lily, a graduating senior, and Maegan, a professor, wrote quietly. In this room where the warm autumnal light danced, we invited our grief to sit alongside us as we held space for each other. Writing about our grief was not new to either of us. Six months earlier, I (Lily) was writing a memoir about losing my mother to cancer. I (Maegan) was working on a book about losing my sister, father, and mother. We were both empathetic to the feelings of vulnerability and the distinct grief-writing-related challenges we expressed to one another during our student hour meetings. Through discussion, we discovered a shared experience of struggling to develop a regular grief writing practice. We also discussed the anxiety we both had sharing our grief writing with others. Further still, we discussed the challenges of adequately responding to another mourner’s vulnerable sharing.

Collaborative Autoethnography

In search of solutions to our struggles, anxieties, and challenges, we turned to research in Communication Studies, Psychology, Composition Studies, and Thanatology (see list of helpful resources in Appendix A). This secondary research provided us with inspiration and a solid foundation to create our own grief writing sessions. We became collaborative autoethnographers working together to create a supportive space. We followed semi-structured journaling guides of our own design. And we engaged with one another’s writing in meaningful ways that encouraged more expressions of care.

Each of our co-designed sessions included time to center ourselves, reflect, write or create art, share, and respond to the other person’s sharing (see Appendix B for specific prompts and design for each session). By engaging with our own grief and listening to each other’s reflections, we grew in our compassion for ourselves, for one another, and for those we have lost. We also realized that this approach to peer grief support would be useful in many other settings. In what follows, we offer lessons to inspire and inform other Expressions of Care workshops.

Ten Lessons Learned

- Take the Time to Connect and Collaborate: We recommend engaging in Expressions of Care sessions for at least four to six weeks and dedicating between 45 and 90 minutes to each session. This weeks-long duration will help deepen your relational connection. The one-hour time range also allows for complex conversations and reflections to emerge. The hour-long sessions gave us enough time to go into depth on at least one prompt per session. We also encourage participants to take the time to get to know one another as people navigating complex losses. For instance, you might start your sessions by naming what brought you to the session and what you are interested in gaining through your time together.

- Set the Stage for Vulnerability & Safety: We set aside one hour each week for our sessions. This gave our grief writing and supportive grief dialogues a “container” in which we could intentionally engage with emotions that arose. We also knew that we could set those emotions down once that hour was up. We came to think of our sessions as liminal spaces, where we could pause the busyness of our days and reflect with intention on our grief. Rather than meet in Maegan’s office, we chose to hold our sessions in a non-academic space. We met in what is known as the “Reflection Room,” in the Spiritual and Religious Life center on our campus. We also co-created guidelines for our time together, including the assurance that it is okay to pass on sharing at any point (see Appendix C for example guidelines).

Setting aside dedicated time, space, and co-creating guidelines enabled us to feel at once emotionally vulnerable, yet safe and supported. We recognize this openness to vulnerability is a privilege related to our whiteness. We encourage your groups to recognize the different lived experiences your members bring into the shared space, considering how senses of safety are often tied to core aspects of our intersectional identities. What feels safe for two white women at a predominantly white institution might not feel at all safe for a Black woman, a nonbinary person, or a neurodivergent man. To establish meaningful trust, we recommend acknowledging the necessary conditions for safety for each of your group’s members.

- Focus on Emotional Regulation: Our sessions were designed, in part, to help us recognize and regulate our emotions around grief. But we found that coming into our dedicated space with a calmed nervous system enabled us to make the most of our time together. We began each session with a meditation to ground us in our shared space. As the weeks went on, though, we also made an effort to bring a sense of calm into our sessions. I (Lily) got into a routine of listening to music on my walk to campus before the sessions. I (Maegan) walked silently from my office to the Reflection Room, focusing on my breath and the feeling of the ground beneath my feet. We made sure to intentionally close each session, as well. To move out of the deep emotional space we cultivated into the buzzing campus life that awaited us, we shared something we were looking forward to or something we were taking with us (an insight, for example) into the coming week.

- Go Leaderless: Acknowledging the power dynamic in our professor/student relationship, we alternated who designed and guided the sessions. We were also mindful about taking turns as we shared our reflections. As you create your own supportive group, be sure to name any power dynamics at the outset. Then strive for a “leaderless” design throughout, by intentionally sharing the floor and the responsibilities throughout your time together.

- Forge Your Own Path: At the beginning of our project, we considered pre-designing all five of our sessions. Upon careful consideration, however, we decided to wait. We designed one session first, discussed how that went, and then designed the next session before we met again. Rather than follow a pre-set path, designing our sessions as we went enabled us to more organically explore topics that arose. For example, our second session focused on mourning mother-daughter relationships because our conversation in the first session veered into this shared experience of grief. Since every group of people will be different and everyone’s grief experience hits differently at different times, we encourage you to consider the sessions we’ve designed as examples for ideas to include, but not as a set curriculum to follow.

- Let Conversations Flow: One of the purposes of engaging in grief writing, art making, and dialogue is processing complex emotions. So we allowed the session prompts to act as a road map, but we welcomed detours. During our last session, for instance, we began by focusing on who we are becoming in our grief. I (Lily) ended up talking about a range of my felt experiences on the day my mom died. That traumatic day was not directly related to the session prompt, but I felt grounded in my body and heard by Maegan in a way that felt more empowering than other times I have talked about that day. I (Maegan) am glad that Lily felt empowered to go where her heart was leading her and to entrust me with this traumatic story. We encourage your groups to foster a similar sense of flow, so that members can flexibly share what organically arises for them.

- Be Open to Alternate Modes of Engagement: We originally thought that our sessions would consist of writing and then sharing our writing with each other. We didn’t anticipate the central role creating visual art would play within our sessions. As it turned out, almost every session we designed had an element of visual artistic expression. Being open to a variety of care expressions–drawing, collage, list-making, poetry, letter-writing, and movement–helped us both access and share difficult emotions and memories. We encourage your group to be open to different modes of expressing care as well

- Check-in throughout the Session: Because we welcomed detours during our sessions, we also frequently checked in about what we wanted to prioritize next from the plans we designed. Sometimes we would prioritize continuing a complex conversation over getting to a prompt we hadn’t yet answered. We learned that a sense of ongoing agency to choose felt just as important for our processing as getting through every prompt we set out for that session. In your group, be sure that the check-ins and decision-making processes are not unilateral or one-sided. While you might not always agree, we found that taking turns with the direction members wanted the session to take helped invest both of us in our shared process.

- Listen, Reflect, and Connect: We both have experience sitting with the discomfort of our own grief. But even with my (Lily) previous experiences processing my own grief, I came into our first session nervous about being able to hold space for Maegan. I worried that I wouldn’t be able to say “the right thing” in response to her vulnerable sharing. Over the course of our sessions, I got much more comfortable not knowing what to say while still holding space for her to share. I realized that like most meaningful skills, holding space for other’s grief sharing takes practice.

During our sessions, I (Maegan) was occasionally reminded of my training as a grief support group facilitator at a community organization. In my training, we learned that there is no “right thing” to say to a person whose parent, spouse, sibling or child has died. Nothing I say will ever be right because it won’t bring their person back. Instead of searching for the right words to say, I’ve learned to listen carefully to the words folks actually share with our group and reflect those words back to them. In the Expressions of Care sessions that Lily and I participated in, I used the skills of reflective dialogue to encourage her continued sharing.

- Carefully Consider Group Size: Our sessions were a partnership, but Expressions of Care sessions could be done in larger groups as well. As group size grows, more structure around who is sharing may be necessary to ensure everyone is heard. On a similar note, limiting group size to six people or less will ensure there is enough time for everyone to share and respond within a 45-90 minute time frame.

As a leaderless partnership, we didn’t have a set structure for responding to each other. Rather, we shifted our responses based on the flow of the conversation. For instance, when Maegan shared about how difficult it was for her to enter a room in her house where she learned about both her father and sister’s deaths, I (Lily) reflected back to her that the space was “filled with grief.” She agreed with my reflection and we began discussing what she could do to reclaim this essential space in her home. In this way, I (Lily) kept the focus on her, rather than sharing spaces in my life that were also filled with grief. Other times, we would connect over shared feelings. For example, when Lily shared with me how much she resembles her mother, I (Maegan) connected with that experience. We both discussed what it’s like to see a person we are mourning in our own reflections.

For us, alternating between moments of focus on one person’s story and moments of conversational back-and-forth worked. For your group, you might need more structure to spread sharing and listening time around. In which case, you might try moving around a circle to share out. Or you might recognize that if one session has really resonated with a particular participant (who shared a lot), the next session should intentionally devote more time to other participants’ sharing.

Parting Words

The two of us came together to do this research at a time in our lives that feels too serendipitous to be coincidental. We were both in a period of intentionally processing our respective losses and were looking for ways to deepen our understanding about grief writing. We connected over our shared questions about how to develop a grief writing practice, how to share our grief expressions with others, and how to compassionately respond to another’s vulnerable grief sharing.

I (Lily) found it powerful to share my story in a space where vulnerability was invited and I knew I would be listened to. I learned so much from listening to Maegan as well. Through our Expressions of Care sessions, I’ve also realized that coming to the table for this type of work does not require being “healed,” only being present. More than this, I’ve learned how to create a “container” for my grief. Our sessions helped me reframe the idea of a “container” away from a place to stuff feelings inside. Rather than a box of all my hard feelings that should never see the light of day, my grief container is a space I intentionally visit. I view it as a place that welcomes me at my most human, includes community, and holds space for the stories of others.

I (Maegan) am honored that Lily shared her time, creativity, and stories of loss with me. Through our sessions, I’ve come to see grief journaling as a countercultural act that can create community. Together, we are resisting dominant societal pressures to move on, return to normal, and “get on with our lives” after loss. I want to continue bonds with those I’ve lost. I want to grow in my compassion for other grievers. And I want to learn new ways to express the care I have for myself, my lost ones, and those in mourning. These sessions helped me do just that. They also encouraged me to embrace the visual arts as a powerful pathway to express care.

Our collaborative autoethnographic research was clearly beneficial for both of us and we want to share what we learned with others. I (Lily) can imagine this guide being used by adults in custody to create Expressions of Care within prison walls and I (Maegan) can imagine friends who might otherwise gather for neighborhood or retirement community book clubs, gathering instead to journal and create art about significant losses in their lives. Our hope is that this article (and its appendices) will be a useful starting point for anyone who would like to engage in meaningful grief-related expressions of care.

Credits

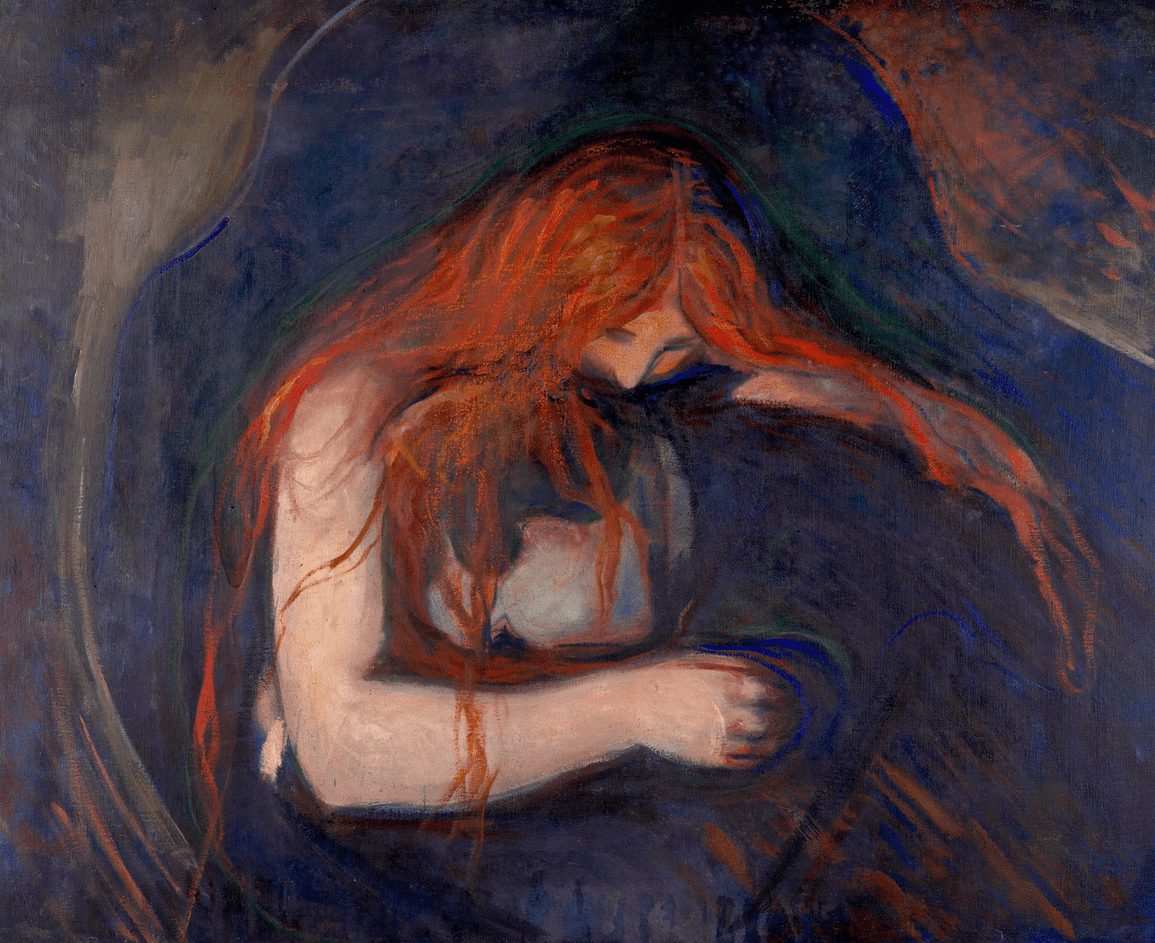

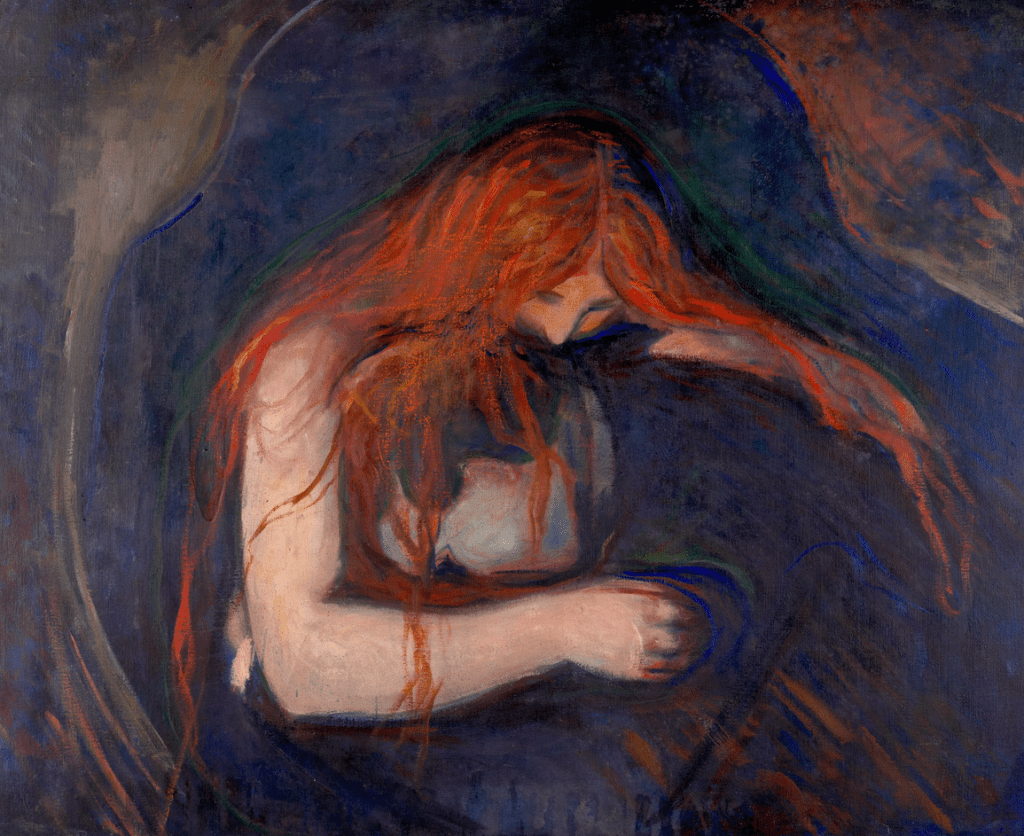

Featured image by Edvard Munch, Munch Museum Norway via Wikipedia

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.