Little Red: The Truth About Growing Up Queer And South-Asian

Author’s Memo

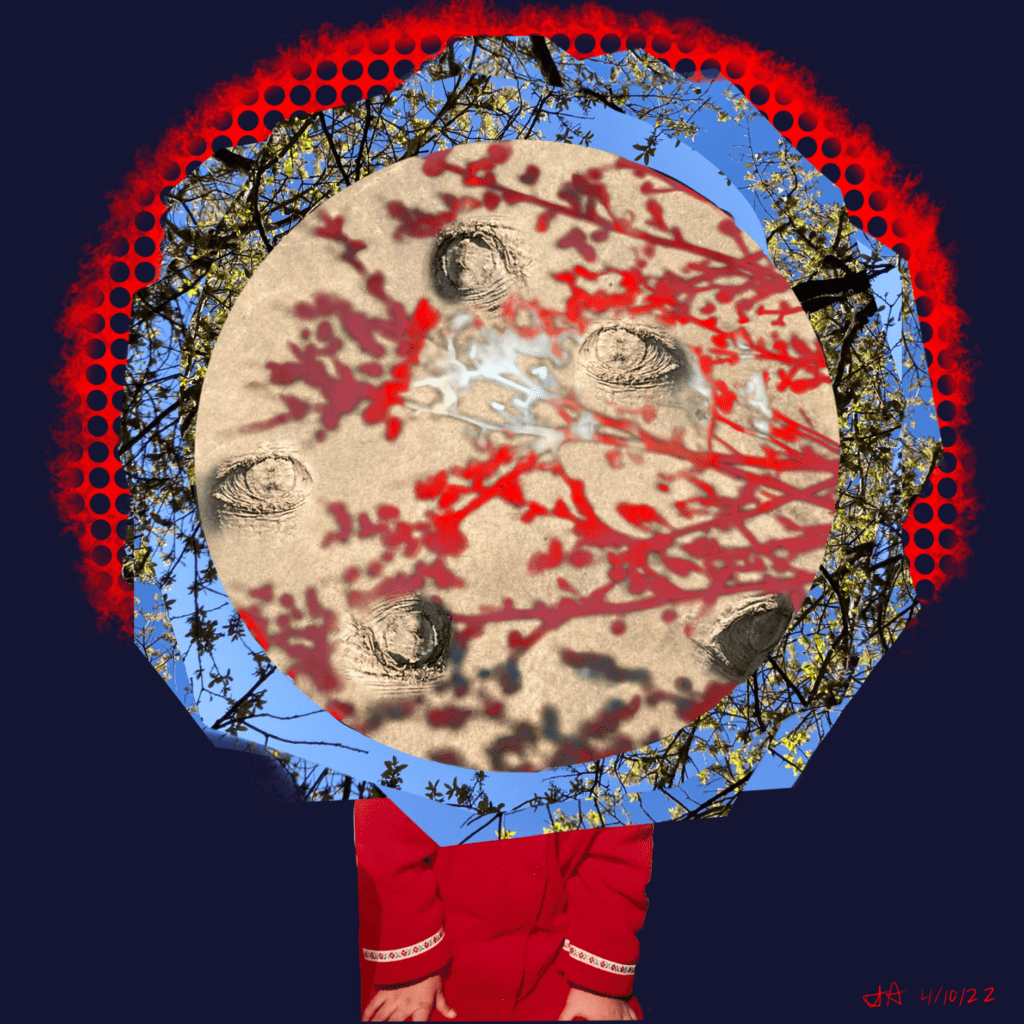

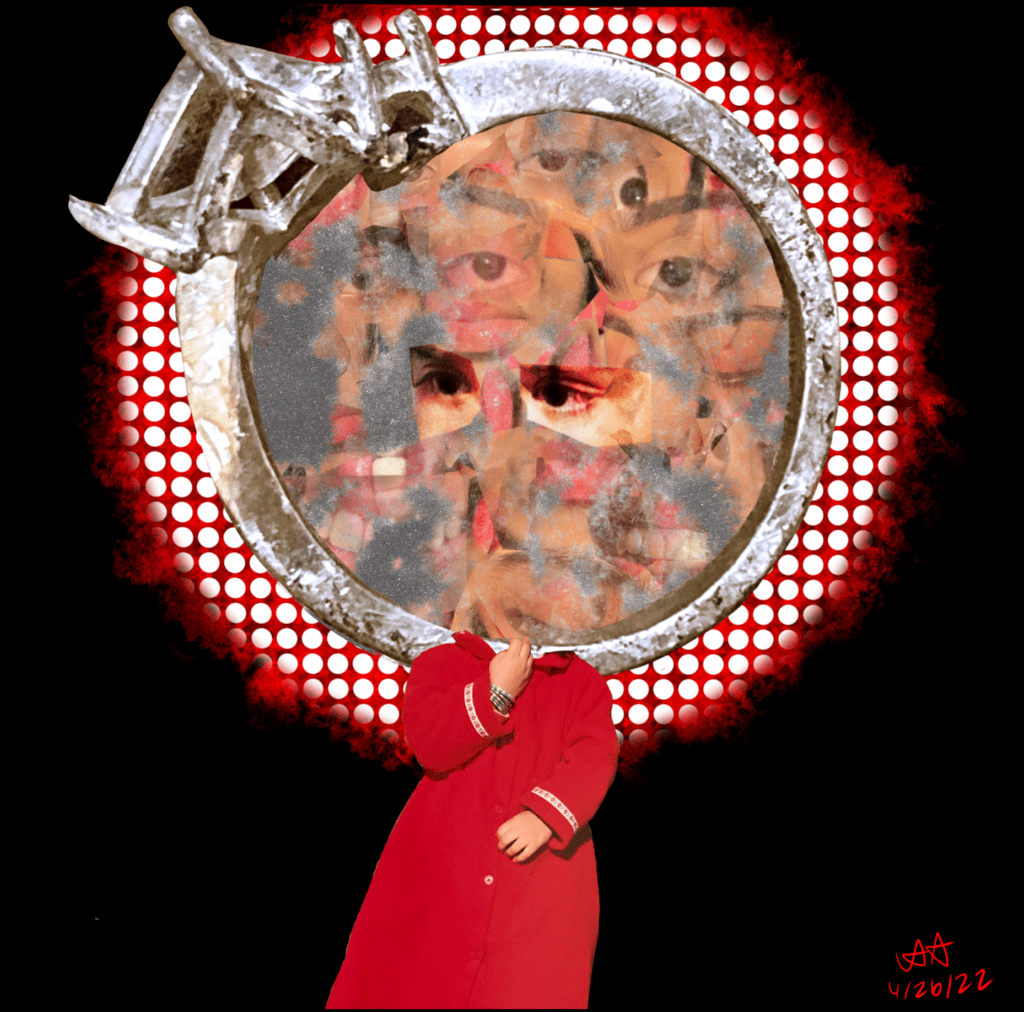

These pieces are a part of my “Little Red” collage series, which revolves around pictures of me as a child wearing a red coat. It explores the idea of how as we grow into our identities as queer women, we learn that the world is not always a welcoming place for us. As a result, we often internalize that hate and become cruel to ourselves, which includes our childhood selves.

The title “She Loves Me Not” is a play on the trope of a person picking the petals off a flower, playing a game of chance as to whether they are loved. This piece is me acknowledging that being mean to myself means being mean to her— my childhood self. This piece was the first of the series and set the tone of comparing my childhood views and adult views.

“Metro” refers to an Ezra Pound poem titled “In a Station of the Metro”– a classic example of imagist poetry. This piece was made after an infuriating conversation with a condescending cis, straight, white man. To me, the poem evokes feelings of impermanence and nihilism. This piece aimed to depict both of those feelings as well as anger. Too many times have women/girls of color had to listen and be quiet around men in power. We are made to feel impermanent. As a child, you learn to accept this impermanence, but as an adult, you realize you have to reject it.

‘It explores the idea of how as we grow into our identities as queer women, we learn that the world is not always a welcoming place for us.

“Eat” connects to the struggle that many South Asian girls face surrounding weight and diet culture. There are always people watching you and criticizing your eating habits as if they reflect your worth. Smaller is always better. It can get to the point where women feel ashamed to eat “too much” in social settings.

The title “Ah hah!” plays on the expression that South Asian aunties would make whenever a little girl was dressed nicely in traditional clothes. The “ah” is short and the “hah” is long and scoops up in pitch. In isolation, the sentiment is nice. But over time, dressing nice stops being about being a cute kid and starts being about becoming a future bride. This is problematic for any young girl, placing this strange and demoralizing pressure on them to be pretty for their hypothetical husbands. For a queer girl, however, this pressure becomes infinitely stronger and infinitely more complicated since their hypothetical future partner may not even be a man.

Overall, “Little Red” encompasses queerness, womanhood, and the implications of growing into an identity that isn’t cherished by society. Despite it all, we must realize that by hating our adult selves, we hate every version of ourselves before that. Each past version of ourselves led to the current version. We hate our teenage selves, our middle school self, and most notably, our child self. As an adult queer woman, I deserve the same compassion and kindness I would give to little me. The outside world operates solely on conditional love. If no one else will care for you unconditionally, then you have to step up and do it yourself.

Credits

Featured image by and the collage belong to Samar Ahmed

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

Raised in a city whose name translates to “yellow,” Sam (she/her) loves bright colors. Primarily working digitally or with acrylics, her work explores identity and young adulthood. When she isn't making art, she can be found studying in a quiet corner of the library for her Biology degree.