Unexpected Activism in Students: What Is Human, Remains

Author’s Memo

Since the purpose of my research is to examine the effects of creative writing processes and its products on the improvement of critical thinking when producing academic writing while particularly demonstrating how this has developed throughout my personal and professional experience, the theoretical framework I use draws from autoethnographic research (Adams et al., 2015; Anderson, 2006; Bochner & Ellis, 2016; Chang & Boyd, 2011; Ellis 1991, 1995, 2004; Hayler, 2011; Spry, 2011). I engage specifically with the descriptive literary approach of evocative autoethnography because it advocates for social change through “a reflexive ideal of conscience” (Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p.80) and invites readers into a relational experience through these stories. While autoethnography allows an examination of complex, intersecting identities because of the dedication to the double vision of individual experiences and social contexts, its emphasis “is the use of personal experience to examine and/or critique cultural experience” (Holman Jones et al, p.22).

Bochner and Ellis (2017) define autoethnography as a “genre of writing and research that displays multiple layers of consciousness, connecting the personal to the cultural” (Bochner & Ellis, 2017, p.563). For Holman Jones (2005), autoethnography uncovers the emotions that “are important to understanding and theorizing the relationship among self, power and culture” (Holman Jones, 2005, p.767) by revealing the ways in which these stories are produced alongside, in this case, pedagogical practices (Chang &Boyd, 2011; Denzin, 2003; Hayler, 2011; Pruyn & Holman Jones, 2018). Autoethnography treats research as a political, socially-just and socially-conscious act (Adams & Holman Jones, 2008) by claiming a transformative or interventionist political stance (Harding, 2008; Madison, 2010).

The theoretical perspective of situated intersectionality (Hill Collins, 2017; Crenshaw, 1991; Hancock, 2007; Haraway, 1991; Lorde, 2017; Harding, 2004; Mohanty, 1992; Yuval-Davis, 2015) reveals multiple factors that exist when analyzing the power relations in academic contexts, particularly in the assumed hierarchy of siloed subjects and acquired skills, with creative writing situated below academic prose. Academic prose in the form of the expository essay is, seemingly, easily enacted and evaluated (Bidwell, 1995; Elbow, 2000). Instructors may use reliable rubrics that students must follow, and so long as there is an adherence to the firm code of conventions and the following of a narrow prescript, both teachers and students can be satisfied with results on high stakes tests or on large scale assessments.

But, as has been demonstrated in university classroom writing (Caffarella & Barnett, 2000; Cotterall, 2011), standardized tests (Biesta, 2010; Gallagher, 2017), and secondary school performance (Graham, Capizzi et al, 2013), students’ writing is sub-par. Only 1 in 5 students in the Ontario college and university system graduate with literacy levels that the OECD regards as basic standards (Weingarten, 2021). In Québec, students must pass the high stakes “Épreuve uniforme de français” or “English Exit Exam” in order to earn their diploma but the most recent reports on student performance (2015/2016 school year) show two areas where students are underperforming: Compréhension et qualité de l’argumentation and Maîtrise de la langue. Almost 40% of students taking the French exam and about 25% of English students scored a marginal pass (or ‘C’) in these areas.

A combined total of 16% failed the test, demonstrating that the formulaic and repetitious writing activities meant to prepare the students are failing them. Across Canada, more than one in six adults fall short of passing the most basic set of literacy tests (Stats Canada, 2013). To write well is an active cognitive ability rather than a passive adherence to a simple formula, so while a basic form can be taught, the imaginative space cannot be assumed through these techniques. The imaginative space can, however, be developed through diverse and variable practice (Bidwell, 1995). Just as diversity in solving complex problems can enhance successful results, so, too, can diverse writing activities improve thought and output (Hong & Page, 2004).

Current research on creative writing looks at creative writing for its own sake, its effect on pre-service teachers (Munday & Cartwright, 1990; Spilkov, 2001; Cautreels, 2003; Pedro, 2005), its effect on critical reading (Knoeller, 2003), its ability to improve other writing skills (Tök & Kandemir, 2015), the need for English teachers to practice it in order to teach creative writing (Milton et al, 2007; Reid, 2009; Thompson, 2010; Blake & Shortis, 2010), how speculative writing can improve idea-making (Singh & Unnithan, 1989), how creative writing can improve language acquisition (Senel, 2018), how creative writing can improve student interest or motivation (Akcay et al , 2010; Selman, 1997), and on creative writing’s impact on poetry-writing creativity (Baer, 1993; Amabile, 1996; Hennessey & Amabile, 1988). There is scant research, however, on how creative writing specifically impacts deeper critical connections between and among course contents.

Whereas critical thinking involves reasoned, logical thinking that acquires and assesses information (Demirel, 2012; Ennis, 1981; O’Hare & McGuinness, 2004) the creative process demands and rouses adaptive, original ideas (Guilford, 1950; Hargrove, 2013).

This particular piece, “What is Human, Remains” looks back at my first year as a teacher, and the unexpected activism in my students.

The creative writer and the academic researcher unite in autoethnography. The researcher is a visible social actor within the autoethnographic text. The researcher’s own feelings and experiences are incorporated as vital data. Past experiences are retroactively and selectively written using hindsight (Bruner, 1993; Denzin, 1989, Freeman, 2004), interviews, and by consulting texts like photographs, journals, and recordings to help with recall (Delany, 2004; Didion, 2005; Goodall, 2006; Herrmann, 2005). Points of entry are ‘epiphanies’ — self-claimed transformative phenomena or moments perceived to have significantly impacted the course of a person’s life (Bochner & Ellis, 1992; Couser, 1997; Denzin, 1989), which reveal ways “intense situations” and “effects that linger — recollections, memories, images, feelings — long after a crucial incident is supposedly finished” (Bochner, 1984, p.595).

These times of existential crises force a person to attend to and analyze lived experience (Zaner, 2004). This is coupled with the study a culture’s relational practices, common values and beliefs, and shared experiences for the purpose of helping insider cultural members and outsider cultural strangers better understand the culture (Maso, 2001). Through participant observation in taking field notes of cultural happenings as well as their part in and others’ engagement with these happenings (Geertz, 1973; Goodall, 2001). Interviews — emergent interviewing, sensory-based interviewing, participatory photo interviewing, and interactive interviewing — with cultural members (Adams et al, 2015; Berry, 2005; Thomas, 2004) examine members’ ways of speaking and relating (Ellis, 1986; Thomas, 2002), investigate uses of space and place (Corey, 1996; Makagon, 2004; Philipsen, 1976), and analyze artifacts (Evnine, 2016; Lake, 2020) and texts such as books, movies, and photographs (Goodall, 2006; Neumann, 1999; Thomas, 2010).

This particular piece, “What is Human, Remains” looks back at my first year as a teacher, and the unexpected activism in my students.

Unexpected Activism in Students: What Is Human, Remains

“For truth is like ordinary light, present everywhere but invisible, and we must break it to behold it.” ~Robert Scholes

Teaching, when done properly, should cause one to feel equal parts buried and buoyed. Both erased by fatigue and drawn anew with elation. Settled into a practiced rut and excited by unexplored vistas. Or at least I believed when I first started teaching, some twenty years ago.

I began my entry to the profession in a small private school where all the students that year came from China to complete a cultural immersion in their final high school year before heading to – grades willing – a Canadian post-secondary school. There was much to prepare in this newly opened school where I would be the only teacher on the third floor while another solitary teacher functioned on the second. To be sure, there would be more of us in the years to come, but that nascent year held a single class of teenaged students who had bravely traversed the globe to continue their education.

Teaching, when done properly, should cause one to feel equal parts buried and buoyed. Both erased by fatigue and drawn anew with elation. Settled into a practiced rut and excited by unexplored vistas. Or at least I believed when I first started teaching, some twenty years ago.

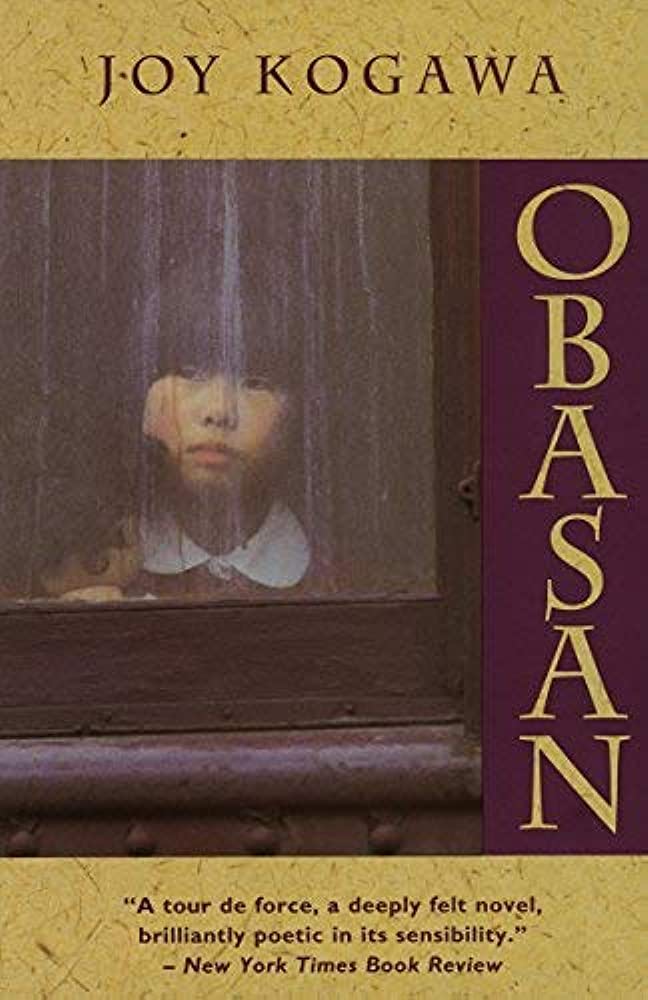

My first task was to create the syllabus, that for me, had to blossom from the choice of novel. I sat in my classroom, the miscellany of cut papers, push pins, posters, and binders cluttered around me. The local newspaper was half open before me to an article. It stated Joy Kogawa’s childhood home, the home her family was forced out of and into an internment camp, and set for demolition. I sat up. This article would be our way into her novel Obasan. We’d start with the story of the house. We could cover a gamut of literary terms here. Metaphor. Imagery. Personification, even. We could look at some Canadian geography. I was sure I had seen a broadcast of people returning to long lost homes after their forced time in internment camps; we could watch excerpts.

As my mind churned over essay prompts and themes of isolation, identity, and of straddling two cultures, I settled the syllabus with Obasan. In the coming days I divided the book and divined group activities and journal topics and presentation roles and vocabulary lists. By the time the novel unit rolled around, I had bundled these activities together. I hung around the photocopier after school hours, making booklets for each student. I carefully stapled the booklets and laid these on their desks, along with a copy of the book, and felt pleased with expectant pride.

On the day when the students filed in, there was a palpable excitement for the things on their tables. While we settled in, and I talked briefly about their packages and what we’d be doing over the next several weeks, one student was becoming agitated.

“For truth is like ordinary light, present everywhere but invisible, and we must break it to behold it.” ~Robert Scholes

I asked him what the trouble was.

She’s Japanese, he said, waving his copy of the book.

Well, I said, she’s Canadian. I was not yet ready to carve the space for our discussion on hyphenated ethnicity.

No, he said. She’s Japanese.

As I was repeating, she’s Canadian, he slowly lifted his book up high over his head, turned it over and snapped it on his desk. One by one, students were turning their books upside down and pushing it to the edge of their desk.

We will not read it, the boy said.

I looked out at them. They were resolute.

I stood for a moment, wondering what I was going to do.

There was a silence that separated us. And a brewing storm.

I was being washed away.

Okay, I said, brushing aside the storm cloud. Take out a piece of paper. Write a journal. It can be a letter to me, to the principal, to the editor of a newspaper, to anyone. I want you to write about why it is important that you only read the books you approve of, and why you reserve the right to refuse the ones with which you disagree, wrote the prompt on the board and I thought I was being clever and it would start a conversation on censorship.

Having not been so far removed from the position of student, and having been a teacher for mere moments, I sided with the students.

They put their heads down and wrote. I walked around the room, collecting the books. Then I sat at my desk, feeling stunned and confused. Of all the things to have happen, this possibility hadn’t occurred to me. Of course, I knew nothing of their story, but that night as I sat reading their journals, I felt shocked and saddened. In the living minds of their families, in the minds of the grandparents who’d raised them, there was an unrelenting anger and unwillingness to forgive they would never relinquish. In a space that I had tried to make safe, I had been careless. I was ignorant of their intergenerational trauma and it had been my job to know better. To have introduced the book, the author, the content more sensitively.

In my head I had litany of reasons to teach this novel still swimming about.

Having not been so far removed from the position of student, and having been a teacher for mere moments, I sided with the students. One must side with the students, I think even now, so many years later.

I had first witnessed student activism in my teacher training program. They placed me with a history teacher and gave me a unit on Ancient Egyptian history. Daunted, but excited, I kept my eyes and ears open to a way in which I could hook the students. I found it in a local news report on the remains of a baby found by a construction crew preparing the ground for a parking lot. There had been, at least at the time, no telling of how long the remains had been there. However, it had been decades at least. Construction halted and they treayed the remains with great care and respect, and later buried in a local cemetery.

After sharing the article with the students, I began to show slides of the discovery and excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Desecration or education, I asked them. Could it be both? Could it be neither? Why offer respect for those here and not for those there? This was, of course, long before I’d hear the horrifying truth of thousands of unmarked graves at residential schools.

When my mentor teacher and I brought the students to the Royal Ontario Museum for the purpose of gazing upon the Egyptian artifacts, our guide led the students to those galleries directly. When we reached the part of the exhibit that housed the mummies, a few students hung back. Thinking they may be trying to slip the group, I headed over and asked if they weren’t coming in. They were resolute. They weren’t.

But we’ve come all this way, I implored.

We offer our respect to the dead by not participating, they replied.

Inwardly, I cheered. Outwardly, I nodded and returned to the group.

But that all seemed so abstract when faced with my students and their refusal to read. I felt there was the danger of making the general blur the particular. In the moment, the conversation was too hot for me to manage. I had no context to support any knowledge. I had not learned to be a listener.

We want our students to become engaged activists and advocates. I wanted to support their protest, even if I didn’t understand it. Perhaps because I didn’t understand it. I went downstairs at the end of the period to speak with my principal. She was firm.

You tell them what to read. They don’t get a choice. You are their teacher.

That was simply a position I didn’t want to take but then how could I allow this ban to flourish? Nothing in this book represented a retelling my students would disagree with or that might warrant dismissing a book for a term. And so began my hope to guide students with what Wilhelm Dilthey refers to as verstehen. The understanding of another experience. I hoped to help my students overcome Othering in their thoughts through Becoming in their reading and writing. Could I help them make a shift in this classroom in Canada?

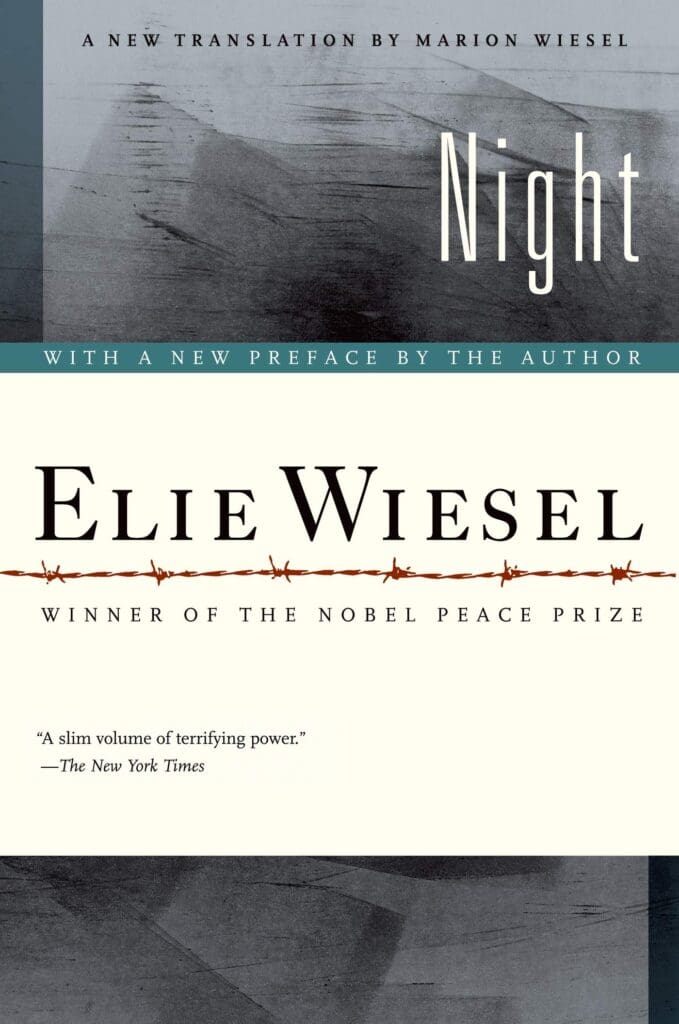

After scrambling, I chose Elie Wiesel’s Night, a memoir of Wiesel’s time as a young boy in Auschwitz. Night is short in terms of page count, so the missed week while we waited for the books to arrive wouldn’t put us behind. But it is dense and cold and sharp. We could write articles, respond to sections in journals and found poetry. Lots of starting points for projects and presentations.

I had no hook that I can remember, but in later years I found a successful point of entry through my favourite piece in the National Art Gallery: Venus by Lucas Cranach the Elder. The artwork had been stolen by the Nazis and you can see it in several images taken by Roosevelt’s Monuments Men: the painting propped up in the dirt; the painting torn from its frame; the painting lost and found. There is clear work with metaphor that can be done. The immediacy of the current, tangible artifact is important to remind the class that the horror is not a general blur of misery and shame, but that it is made up of particular, personal, and achingly painful human stories. We cannot simply look away and forget.

But there was a suggested classroom activity for the memoir that I was willing to try. Early on in the unit, I was to stage a reading quiz. I was to ‘catch’ a student cheating. This student would be a hardworking, trustworthy student whom no one would be able to believe was cheating. I had already asked a student, Brian, if he would help me with this activity. He agreed. We were both ready.

While the class was writing the quiz, Brian kept looking up at me, with readiness and confidence. He was poised. I was supposed to start yelling. Yelling that he was to cut it out and stop cheating. Brian was supposed to deny the cheating. I was supposed to throw him out of class and tear his quiz paper into little bits. Those around him would have known he wasn’t cheating. Would they come to his defence? What about the others that knew him well? Would they defend him? How would the class respond?

In truth, when it came down to it, I just couldn’t do it. I couldn’t yell in the classroom. I couldn’t accuse a student of cheating, even if we were both in on the ruse. When the teacher corrupts the delicate trust in the classroom, it is very nearly impossible to rebuild. It also felt like it would be a shameful move in exercising absolute power. And if I didn’t manage the manoeuvre successfully, the memory of my deception would be far brighter than the intended lesson.

Instead, deflated, I told the students what Brian and I had been planning to do. How I was to have yelled at him, to have accused him, and to have sent him out. It ruined the writing activity, of course, which was for the students to question why they had or hadn’t stood up for Brian. Instead, I asked them to imagine what they would have done. But certainly, we can’t ever know with these kinds of hypotheticals.

Yet, the refusal to read a novel – any novel – never repeated in the years that followed at this school. Not for Obasan or any others. Students laughed at Ezra Pound’s feeble and inaccurate attempt at translating The River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter. However, there was never again a protest against reading any particular author or piece. Though it waxes and wanes, teaching is never equal parts of anything. If we are lucky, we give to the marrow, to the ash, to the final breath of each day. And if we are even luckier, our students will move on with greater insight to their purpose.

But for that first group where I had acted carelessly, I learned lessons of hope. After finishing Night, I casually mentioned that I had included Obasan on the Independent Reading list, in case anyone would like to choose it. Three students did choose to read it and presented their reading to the class. I had about 25 students, so not many. Not many but not nothing. And that might be the only great success of my teaching career.

Credits

Book Cover, Obasan by Joy Kogawa: https://www.amazon.com/Obasan-Joy-Kogawa/dp/0385468865

Book Cover, Night A Novel Elie Wiesel from Amazon.com: https://www.amazon.com.tr/Night-Hill-Wang-Elie-Wiesel/dp/0374500010

Featured Image By Patrick Tomasso for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work? Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition.

I am a PhD candidate at McGill University, researching the imbricate edges of teaching, creative writing, and critical thinking.