Despite their seductive aesthetic beauty, I have no desire to simply paint images of birds without also including the destructive baggage of human culture. For me, to do so, would be a form of escapism that ignores the apocalyptic ecocide currently unfolding on the planet, the fact that the human species has dramatically altered the natural systems upon which all life depends through advancements in technology. Like the story of Frankenstein, my mutant birds serve as vehicles for allegory and satire.

AUTHOR’S MEMO

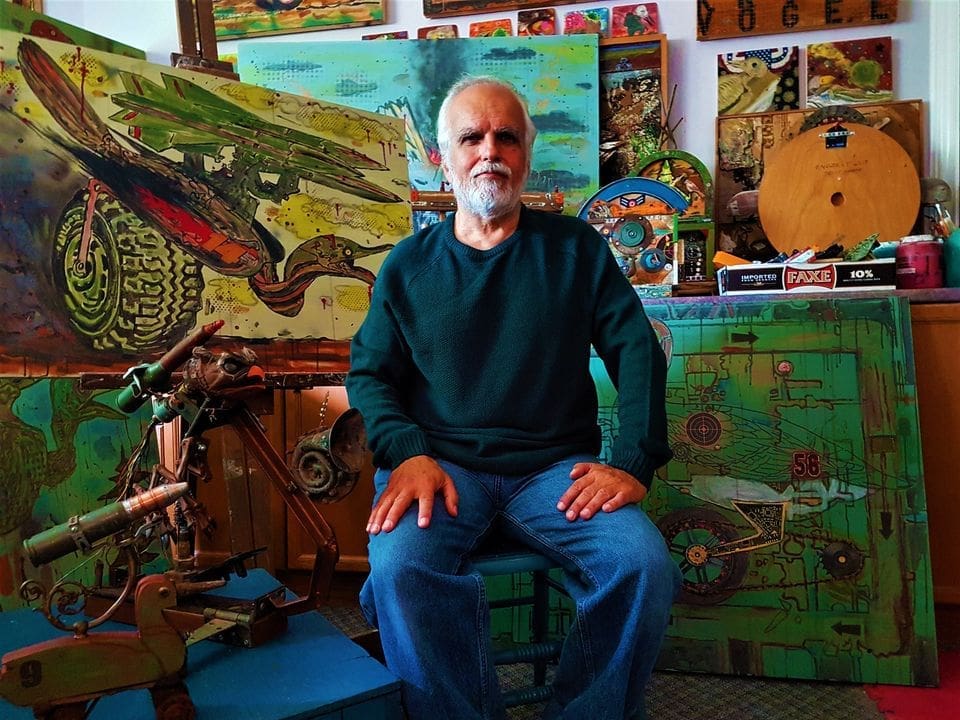

Terry Graff is a visual artist and an avid bird watcher. Birds consistently appear throughout his work, and have been a persistent theme since childhood. Through word and image, he recounts his childhood memories of birds, tracing the important influence that his early experiences and drawings of birds have had on the development of his present-day artwork. Far from an expression of the seductive aesthetic beauty of birds, Terry presents a phantasmagorical vision of the “avian cyborg”, bird-machine hybrids that speak to the conflicted relationship between nature and technology and the dramatic catastrophic disruption of the natural systems upon which all life depends. They are allegories for our human condition in an age of ecological collapse.

In Part 1, published in March 2022, Terry began his exploration of birds in his work with an examination of his childhood drawings: Autoethnographic Art and Essay: Ode to Bygone Birds of Childhood, Part 1 – Drawings

“In retrospect, it was inevitable that birds and machines would converge in my work as a life-long exploration and expression of the relationship between nature and technology through the creation of avian cyborgs, the genesis of which can be traced back to my early drawings of robots and of the bygone birds of my childhood.”

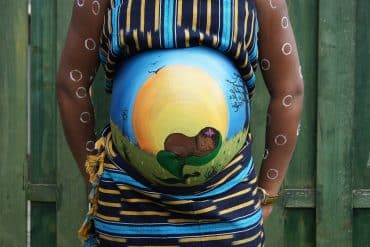

Photo of Terry Graff

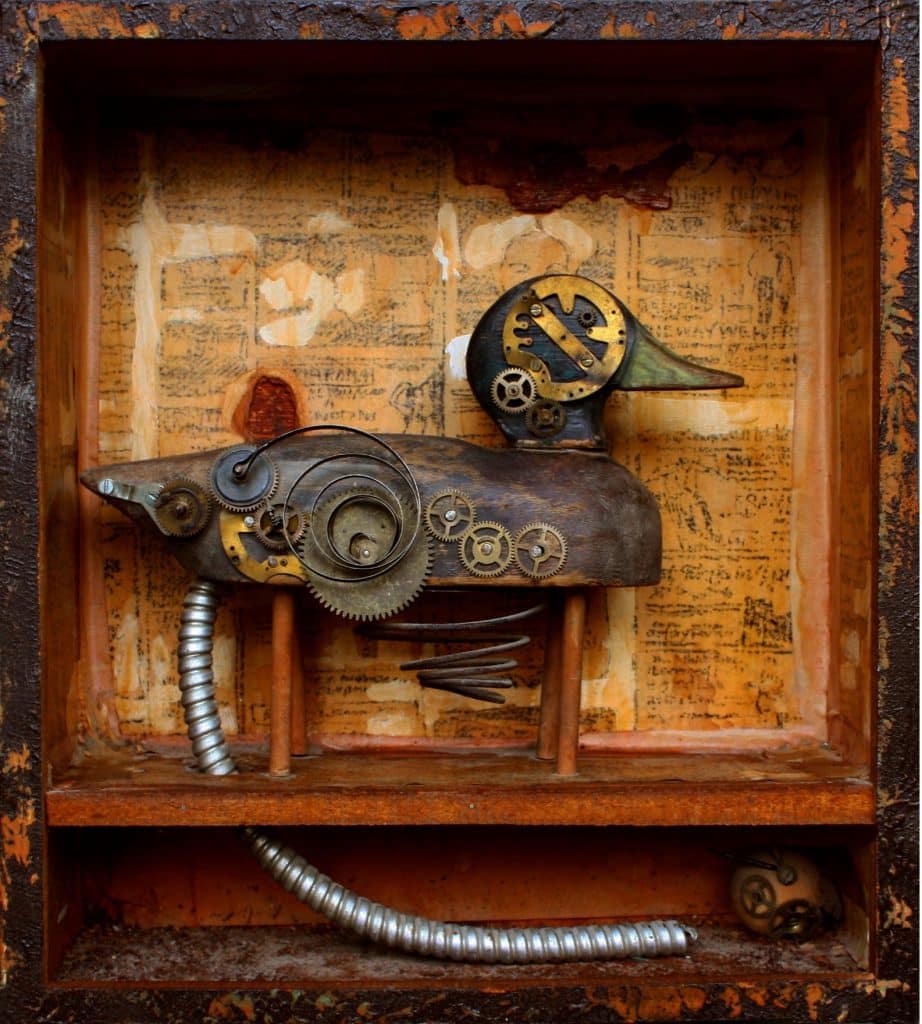

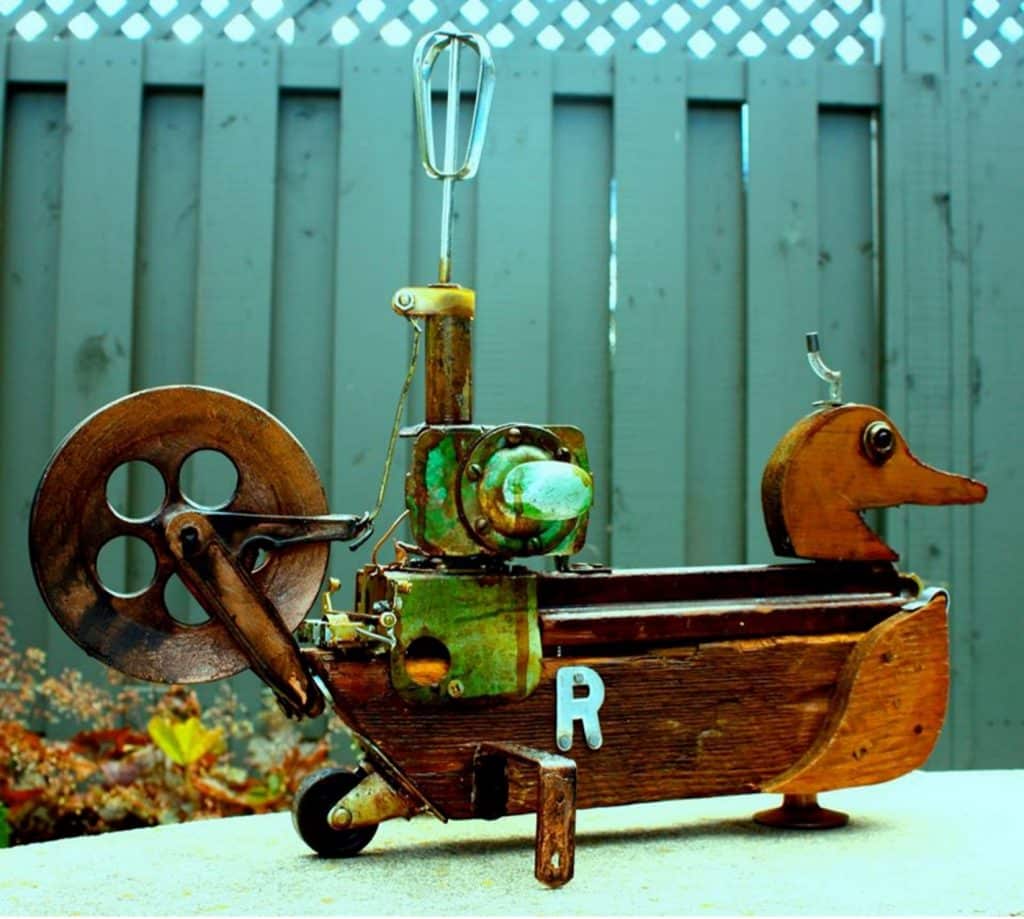

In 1974, when I was an art student at Fanshawe College in London, Ontario, I created my very first machine-duck hybrid sculpture, a “steampunk” clockwork canard Quack-in-the-Box. This techno-fantasy work marked the beginning of an extensive series of junk sculptures and assemblages that focused on fusing ducks and other birds with machinery as a visual expression of the process of becoming modified or transformed for survival in an ever-evolving, often brutal, technological world. As we use technology to increase our human capabilities, we consistently make ourselves more vulnerable to its evil dark side. The title “Quack-in-the-box” is a reference to the first jack-in-the-box made by a German clockmaker in the early 1500s who had a devil pop out of the box after turning the crank, a fitting analogy for how our technological advances have contributed to numerous ecological disasters throughout the world and to climate change.

QUACK-IN-THE-BOX, 1974, mixed media assemblage

My initial inspiration for this direction was triggered by my employment in many local factories, machine shops, and the parts department at General Motors. I also read about the French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson (1709 –1782), who made several innovative automata, such as “The Digesting Duck”. His mechanical duck contraption had over 400 moving parts in each wing alone, and could flap its wings, drink water, digest grain, and even defecate. Incidentally, while in the process of building the duck’s intestines, he inadvertently invented the world’s first flexible rubber tube.

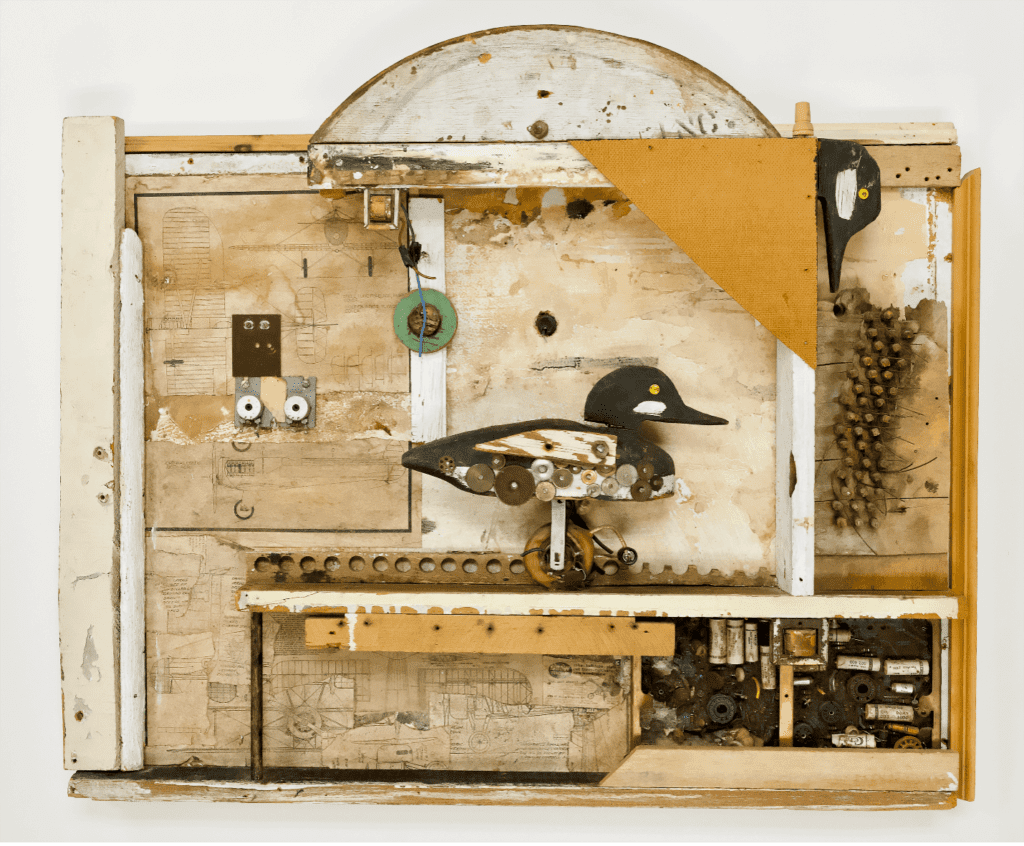

ORNITHOTRONIX, 1979, mixed media assemblage

Some of the first complex machines in history were automata, by means of which human beings attempted to simulate nature (or imitate life) and domesticate natural forces. Among the plant life of early gardens were mechanical curiosities, such as hydraulically operated singing birds and other biological automata. The earliest example of a robotic bird dates back to 350 B.C.E., to a mechanical wooden dove created by the Greek mathematician Archytas of Tarentum, father of the science of mechanics. Powered by some sort of compressed air or internal steam engine, it flapped its wings and flew a distance of 200 meters. In his treatise on pneumatics, the Greco-Egyptian mathematician and inventor, Heron of Alexandria, also called Hero (c. ad 62), featured designs for several different types of artificial birds that could move and sing in response to flowing water that pushed air through small tubes and whistles concealed within carved birds. Over the centuries, many other inventors became intrigued with mechanical birds, including Leonardo da Vinci, who created several imaginative designs for flying machines based on his intensive studies of flight, as well as a mechanical flying bird for a stage production.

DOOMSDAY CUCKOO CLOCK, 2021, mixed media assemblage

As a child, I was fascinated by the German cuckoo clock, which became popular in the 18th century in the Black Forest region of Baden-Württemberg where my Graff ancestors originated. Handmade out of wood, the cuckoo clock evolved into numerous innovative designs with intricate gear mechanisms and birds that had moving wings and fluttering feathers and a cuckoo call created with bellows and whistles. I have a precious memory of making my own cuckoo clock when I was six years old. We were scheduled to make clocks in kindergarten, but I got sick that day and had to stay home from school. I recall how upset I was because I loved making things, but was soon smiling when my mother provided me with construction paper, cardboard, scissors, mucilage glue, and crayons. I spent a full day working on my clock while sick in bed, and it was not the simple formulaic paper pie plate clocks that my classmates were instructed to make. I made a three-dimensional cuckoo clock replete with a bird that would pop out when you opened the little door. Although dark in theme, my recent series of working Doomsday clocks, including a warbird cuckoo clock, derive from this magical childhood memory.

MARSH INSTALLATION #1 (Tantra Mantra), 1990, multi-media kinetic sculpture

In the 1980s and 1990s, my Ornithotronix and Dux ex Machina assemblages and drawings, which can be viewed as an expression of the displaced victims of a fragmented socio-economic environment, evolved into full-scale mechanical simulations of wetland environments (Tantra Mantra) and other ecological systems replete with robotic decoys and machine-driven, cast-aluminum migrating waterfowl (Season of Return). These immersive “Eco-Deco” performance-installations were created from a wide range of recycled materials, some of which included neon and other theatrical lighting effects, were driven by an assortment of motors, and featured audio tracks comprised of mash-ups of electronically altered sounds from both natural and industrial landscapes and even an elaborate musical narrative composition created by my musician brother. Over the years I made several kinetic bird sculptures, such as motorized whirligigs, eggbeater ducks, and an electronic woodpecker that rapidly pounded its head into a piece of metal, creating a loud industrial noise and excessive vibration that caused the release of an artificial pine odor. In those days, I was experimenting with different kinds of machines and once attached a weed-eater to one of my decoys, which ended up spinning out of control in my studio, ricocheting off the walls and ceiling and almost taking my head off.

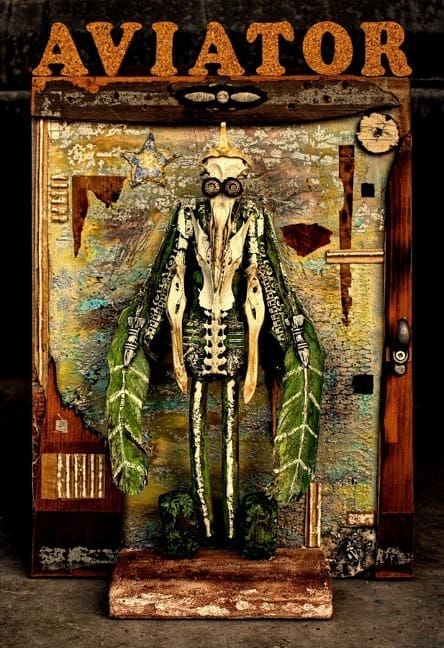

AVIATOR, 2018, mixed media assemblage

I have made numerous works without spending any money, as recycling or re-purposing of diverse materials and cast-off found objects has always been a key ingredient of my creative process. The alchemical transformation that occurs through recombination of scrap wood, cardboard, machine parts, electronic components, broken toys, and other cast-off detritus, has provided a potent means for expressing the mysteries, complexities, and contradictions of life. In some of my pieces, the threat of dissolution inherent in many of the materials I use, and my wilfully destructive approach to artmaking (breaking, burning, tearing, hammering, drilling, melting, etc.) are suggestive of the transformative entropic and negentropic processes in nature that is the subject of my art.

DOOMSDAY CLOCK #3, 2019, mixed media assemblage

Once, on my way to install an exhibition of my work, one of my large-scale duck assemblages blew off the roof of my vehicle and shattered into multiple pieces on the highway. Undeterred, I picked up the pieces, reassembled them into a different configuration at the side of the road, and delivered it on time for the installation. The altered work received critical attention for its “innovative use of materials and ‘road warrior’ patina.”

WARGAME, 2019, mixed media assemblage

My orchestrations of abandoned junk are inspired by the first museums, or “wunderkammern”, cabinets of curiosity that combined natural and artificial marvels of the day. Since the new millennium, I have created post-apocalyptic aviaries in the form of reliquaries that often include quirky visual source material from my childhood encoded or embedded with cultural constructions of nature and that reference old-fashioned shooting galleries and pinball machines. From time to time, I have also added certain performative aspects to my work, such as setting fire to one of my duck decoys and sending it over Niagara Falls.

HIGH RIDER, 1979, mixed media drawing

The duck decoy is a dominant motif in my work, embodying the process by which art and reality are not only related, but interchanged. As identified with duck hunting, the decoy is an artificial bird, or more accurately, the likeness of a waterfowl employed as a lure to entice real ducks within range of the hunter. Art is also a decoy, or as Picasso called it, “a lie that makes us realize truth”. My teacher at art school, sculptor Don Bonham, said, “in order to have a convincing fantasy, you have to have quite a bit of high reality”.

DECOY #6, 1987, mixed media sculpture

In 1987, when I was living in Sackville, New Brunswick, I constructed a series of decoys which I loaded in the back of my station wagon and chauffeured to a nearby duck pond. There, reveling in deception, I allowed my art to mingle with a group of unsuspecting, although curious mallards. I wanted to explore how abstract a decoy had to be before its powers to deceive broke down, before it would no longer be read as the real thing in nature. I was absorbed by how images could be mistaken for objects and how objects could be mistaken for images. To further the project, I featured four live ducks in my “Sitting Ducks” exhibition at Struts Gallery, which wandered about various machine-duck assemblages and an artificial duck pond. The event featured real quacking, real feathers, and real duck droppings.

MARSH INSTALLATION #1 (Tantra Mantra), 1990, multi-media kinetic sculpture

During seven years spent in Sackville, New Brunswick, I explored the Tantramar Marshes, which is situated along the Atlantic flyway, and studied the diversity of waterfowl found there: Mallard, Blue and Green-winged Teal, Ring-necked Duck, Northern Shoveler, Coot, Wood Duck, Blue Heron, and many more. This environment, along with the books I was reading at the time, subjects like Deep Ecology, Bioregionalism, Ecopsychology, Animal Rights, and the Culture of Nature, etc., had an enormous impact on my thinking. At the same time, I was researching bird symbolism in different cultures, religions, folklore, superstitions, and traditions throughout the world, specifically ideas about the transition between life and death associated with birds, and discovered a wide range of very particular meanings associated with different species of birds.

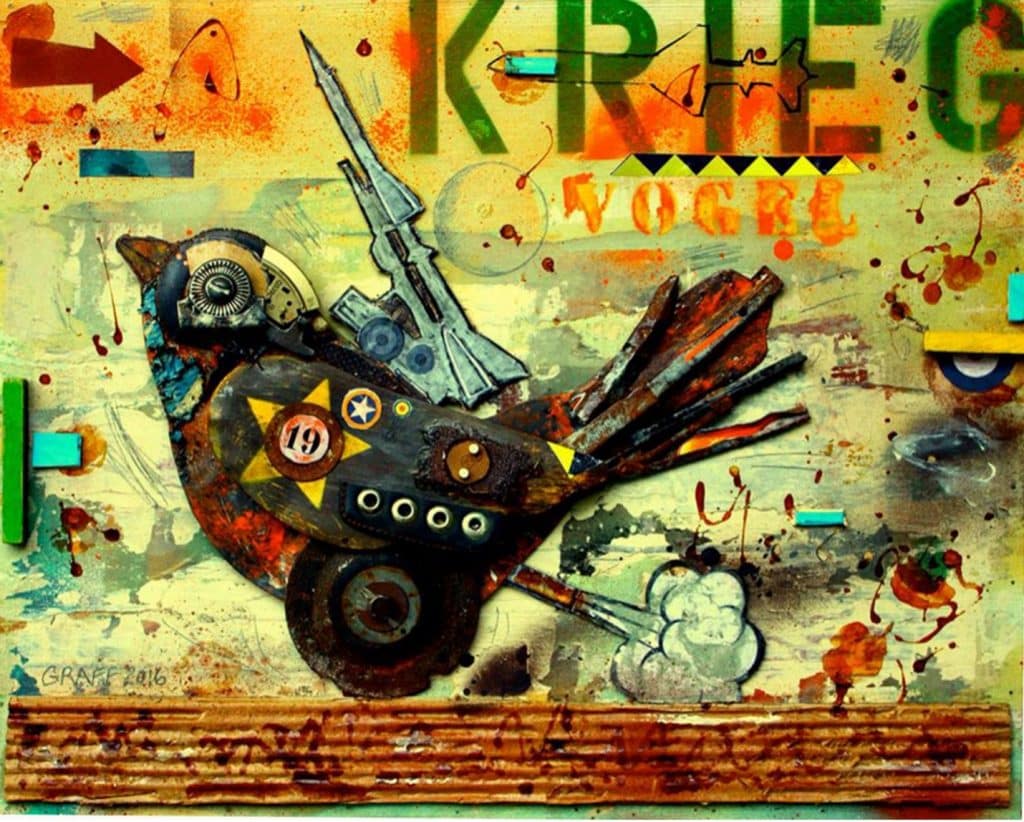

KRIEG VOGEL, 2017, painting/collage on wood panel

As human beings, we project our human values and cultural assumptions onto the natural world. By exaggerating the anthropocentric way in which we see the nonhuman other by literally attaching artifacts of human culture to a bird, I aim at underscoring how we promote human interests at the expense of the interests or well-being of other species, the idea that other species do not exist for our benefit but, like us, are part of a whole ecological system.

SUICIDE BOMBER, 2017, acrylic on canvas by Terry Graff

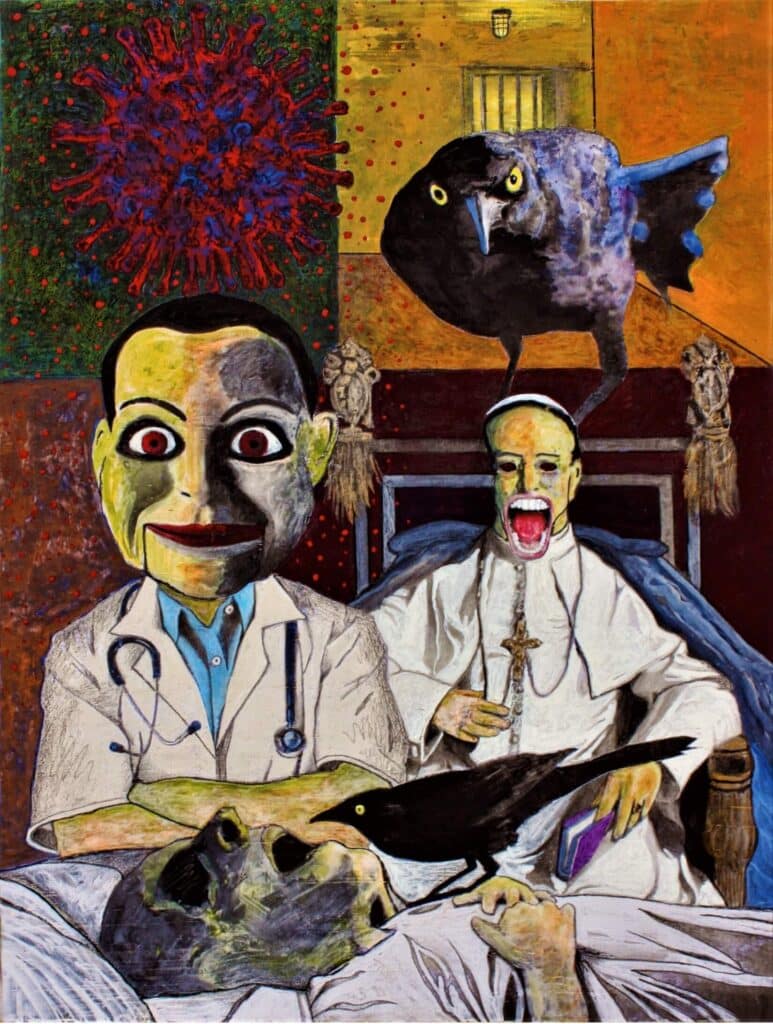

COMBAT MEDIC, 2016, acrylic on canvas

Despite their seductive aesthetic beauty, I have no desire to simply paint images of birds without also including the destructive baggage of human culture. For me, to do so, would be a form of escapism that ignores the apocalyptic ecocide currently unfolding on the planet, the fact that the human species has dramatically altered the natural systems upon which all life depends through advancements in technology. Like the story of Frankenstein, my mutant birds serve as vehicles for allegory and satire.

END OF TIME, 2020, acrylic on wood panel

Although the wonders and benefits of technology are often cited as great achievements of the human species, technology is, at the same time, quite literally destroying the natural world. Birds are being killed in ever-increasing numbers by crashing into buildings, transmission towers, oil rigs, wind turbines, solar panels, and other infrastructure, and also by the destruction and loss of their habitat, by the electromagnetic radiation from power lines and cell towers that disrupt their magnetic “compass”, by the mountains of toxic waste and unrecycled plastics that have infiltrated all of the world’s ecosystems, and by global warming, the greatest threat to birds and other wildlife in human history.

WARBIRD WITH MUZZLELOADER HEADGEAR, 2019, acrylic and mixed media on wood panel

Survival of a species depends on the ability to make use of energy potentials in the environment. Through evolution, the duck has become a highly sophisticated and versatile survivalist. It walks, flies, swims, dives underwater and even vacations in Florida during the winter, achieving tremendous freedom over the limitations of the natural environment. However, no adaptation is permanent, as the world is in continuous flux. In response to climate change, ducks and other birds must adapt quickly to shifts in temperatures by migrating to cooler climates, modifying their diets and altering their breeding cycles. My work imagines them turning to technology for survival, adapting to a machine-oriented rather than a biologically oriented world by transforming into cyborgs.

THE WOUNDED WARBIRD, 2017, acrylic on wood panel

For human beings, the human-robot hybrid is not a figment of science fiction, as we have long augmented our bodies with non-biological parts, and are remaking animals into mechanical devices to serve human ends. Scientists are looking to pollen-coated drones as replacements for bees and other disappearing pollinating insects, and currently a smartphone can control electrodes implanted in a cockroach. Micro-electrical mechanical systems (MEMS) introduced into the larval stages of insects may be a significant step forward for performing complex medical procedures, but it also introduces to the world the possibility of new weapons of war.

WARBIRD #8, 2019, mixed media sculpture

My more recent work, the “Warbird Series” focuses on the fusion of birds with war machinery and combat weaponry in a black comedy of avian anarchy as nature takes up arms to fight back for its very survival. Although a fantasy, these works were inspired by the childhood experience of being divebombed by a robin defending its nest, by being chased and bitten by a Canada Goose, and by being mobbed by a gaggle of Chinese geese after my lunch. Just as symbiosis and harmony can be witnessed in nature, so too is war a natural occurrence, as birds will fight to defend their territory, to protect their offspring, to maintain their food supply, and to achieve dominance as a species.

PERPETUAL MIGRATION, 2000, painting/collage on wood panel

Although environmental issues influence my art practice, I do not define my work as eco-didactic, but as a vehicle for documenting, expressing, and interpreting how the world feels. I don’t expect viewers to interpret my work the way I do, as art can have multiple interpretations and can, in fact, be contradictory. I employ both humour and horror in my work, and often blend these two genres to play on different emotions and to deliberately subvert expectations. Black humour encourages us to laugh where we might normally be terrified and to shutter with fear where we might typically laugh. Paradoxical, provocative, and transgressive, it can be a potent weapon for social and political protest, and in many cases, it’s a cathartic way of expressing a horrific experience. Whether dealing with the fear, the politics, the suffering, and the many tragic deaths during the Covid-19 pandemic, or with the gravity of impending worldwide ecological collapse in times of climate change, it offers a defense mechanism against despair, a means of releasing tension from the distressing precariousness and anxiety that we are all experiencing today.

EXORCISING THE DEMON, 2020, acrylic on wood panel

As the world’s bird populations decline precipitously, will the many winged creatures we knew as children live only in the mists of memory? Further, are we so different than the birds of the air? Is humankind destined to become a victim of mass extinction? Can we ever get back to the garden again? Or are we capable of adapting to a rapidly changing environment, of ensuring our survival through the use of our technologies? The avian cyborgs I create derive from reflection on these critical questions. They are allegories for our human condition, a mirror image of ourselves as we try to understand the dystopian world we unthinkingly created and now inhabit.

Featured image by author