Spiritual Garnish: The Truth About Western Yoga Spaces

Author’s Memo

Though my background is in creative practice, I have practised yoga since 2016 in various parts of the World and was awarded a 200-hour teacher training certificate from Nepal Yoga Academy in July 2022. Throughout these experiences, I have gained insight into the distortion between how yoga has originated, and how it has been adopted into a western context.

Yoga is historically linked to colonial trauma. Though originally a methodology for spiritual liberation, modern yoga is commonly portrayed as physical exercises with spiritual ‘garnish’. In the current age of permacrisis many westerners seek practices that promote wellbeing, including the increasingly available appropriated, context-divorced and commodified versions of yoga—targeted towards a predominantly middle-class female demographic. This has led to a second wave of colonisation, and tensions concerning appropriation, gender and identity that require intervention. Written by a white, cisgender, male yoga practitioner and newly qualified teacher from a working-class, Northern English background, this autoethnographic account seeks to elucidate upon how the issues noted may manifest.

‘Yoga is historically linked to colonial trauma.

Some aspects of the tensions noted above have attracted some attention in a recent period. For example, Graham (2022) discusses the commodification of yoga from a non-white perspective, and Bhalla and Mascowitz (2020) discuss the objectification of female yoga practitioners. However, there remains an absence of understanding of the impact of the identified tensions from the perspective of white, western working-class, male-identifying yoga practitioners/teachers (to whom such tensions may be particularly relevant). An autoethnographic lens allows for a layered, nuanced, and rich presentation of the themes mentioned.

References

Bhalla, N., & Moscowitz, D. (2020). Yoga and Female Objectification: Commodity and Exclusionary Identity in U.S. Women’s Magazines. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 44(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859919830357

Graham, D. S. (2022). Yoga as Resistance: Equity and Inclusion On and Off the Mat. Watkins Media Limited.

by Julia Caesar for Unsplash

The problematic nature of the supposed ‘yoga’ industry

‘Yoga’ as we commonly understand it is not really yoga. At its origin, the term yoga relates to an array of philosophies ultimately concerned with the union of the self/soul and God/super soul. When utilised in a contemporary western context, the term typically refers to “modern postural yoga”—that is, a practice that involves participants engagement with various asanas (postures) in a sequence (Michelis, 2005, p.249). Despite being a contextually isolated and often appropriated form of yoga, it is understood that modern postural yoga still provides some benefits. This has been capitalised on in the West to create a yoga industry, with five billion dollars being spent on yoga activities in the USA in 2010 (Stephens, 2010, p.40).

The increased popularity of ‘Yoga’ and cultural erasure of Yoga

With the 2020 global pandemic and the anxiety induced by living in the age of ongoing ‘permacrisis’ (Zuleeg et al., 2021), millions of individuals turned to ‘mind-body’ practices including yoga in an effort to improve well-being (Hart, 2020). This has further elevated the popularity and presence of yoga in the West, and thus the marketplace has been increased. As yoga spaces become more normative, so too does the perpetuation of practices that are context-divorced, appropriated, and inherently rooted in colonial trauma, white supremacy, and cultural erasure (Barkataki, 2020, p.59).

Yoga—once banned in India under British colonialism (Barkataki, 2015)—is now branded as a facet of the fitness industry and typically marketed towards and practised by a middle-class, white, female demographic (Nalbant et al., 2022, p. 6). In addition to often overlooking the non-physical benefits of yoga (which are its essence), this modern presentation of yoga that contributes to a second wave of colonialism (Barkataki, 2015).

Complexity and tensions in Western Yoga spaces

Modern yoga thus presents tensions for western practitioners regarding 1/ cultural appropriation, and 2/ the increased presence of male yoga practitioners in predominantly female spaces. It is critically important to make conscious steps towards preventing further inequities from occurring and take steps towards remedying those that exist. This is particularly relevant in a post #metoo era and a period of self-reflection, following the social upheaval that ran concurrent to the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘Though originally a methodology for spiritual liberation, modern yoga is commonly portrayed as physical exercises with spiritual ‘garnish’.

The female-centred landscape of modern yoga can (and historically has) result(ed) in predatory and abusive male behaviours. This adds a layer of complexity of tension for reflexive male teachers and practitioners concerning both social harmony in regard to gender inequities, and perceived sense of ‘masculinity’ when present in female-centred middle-class spaces. As stated by Atherton (2019) in relation to men from working-class backgrounds, “If the masculinity in which males identify does not correspond with the dominant in the field in which they live, then they may experience internal conflict with their identity” (p.46). Similarly to Obasi’s (2022) findings on the complexity of oppressive experiences of Black female social workers in Northern England through an intersectional lens, modern yoga thus presents nuance in tensions from a working-class male perspective.

Written by a white, cisgender male from a working-class, Northern English background, this autoethnographic account of attendance at a yoga workshop conducted in Manchester by an internationally recognised western teacher seeks to elucidate on how such tensions are present and the ways in which they may manifest.

Autoethnographic account of a Yoga Workshop: March 2023, Manchester

Although I understand that the workshop that I will be attending is carried out by an internationally recognised white male yoga teacher—and within a two-hour window—on the morning of the workshop I still believe that I will soon be entering into a space that corresponds with my previous experiences of practising yoga asana in my local yoga studio in Stockport.

Perhaps this belief is the result of being immersed within a yoga space that alligns with the spirit of that of my experiences in the yoga teacher training centre I attended nine months prior in Nepal—spaces in which non-physical components of yoga are integrated into the physical; where attention is given to the sensation rather than ‘perfection’ of posture; the source of origin of teachings are acknowledged and celebrated, and gravity is placed upon the lineage from which the practices emerged. I had utilised and benefited greatly from the particular yoga teachers’ online videos during the pandemic period, and despite the physical challenge present, I always found his classes to be integrative of both physical and non-physical components of yoga. This was the understanding that I approached the workshop possessing—but not the one that I left with.

‘In the current age of permacrisis many westerners seek practices that promote wellbeing, including the increasingly available appropriated, context-divorced and commodified versions of yoga—targeted towards a predominantly middle-class female demographic.

When I came across an advertisement for the workshop with the particular practitioner, I was excited to book a place. This was a teacher from the USA who was coming to a city in Northern England to offer a series of classes over three days. The cost of attendance was reasonable considering the location. I immediately messaged the hosting studio requesting to book onto a session focussing on back bends—as despite the reasonable cost—attendance at the entire workshop was still outside of my budget. The hosting venue was a studio in a mill in Manchester city centre, that seemed to have been recently established. The venue website boasts that the owner has taught yoga all over the world, including to an “A-list clientele” in Los Angeles, where the owner has previously lived and worked.

I didn’t receive a reply to my message for the specific day requested but did receive acknowledgement of payment received. Four days prior to the workshop I contacted the studio via social media to confirm if my requested slot had been booked, and received a reply stating, “all good [thumbs up emoji]”. I assumed that perhaps the lack of communication to be due to the difficulties that I assumed to arise in establishing a managing a large-scale new project such as a yoga studio. I wasn’t sure if I needed to bring my own mat or if they would be provided, and this information wasn’t anywhere to be found on the website.

‘This has led to a second wave of colonisation, and tensions concerning appropriation, gender and identity that require intervention.

I rolled my £10 budget mat into a carry case, and a little later than I would have liked, rushed to the bus stop to arrive at the workshop on time. As I travelled on the surprisingly busy bus I was filled with excitement, enthusiasm, and a degree of nervousness to be taught by a practitioner that appeared to possess expertise and approach the practice with authenticity. At the same time, I felt an anxiety about my presence at a workshop in a major city as a non-expert and male practitioner in what has been presented in the West as a female-dominated space.

‘Northern English background, this autoethnographic account seeks to elucidate upon how the issues noted may manifest.

After hurriedly approaching the mill and walking up the (many) stairs, I arrived just 5 minutes before the workshop was due to start. I was conscious and embarrassed of my physical displays of exertion when entering a space in which competitive athleticism and impossibly beautiful people are present. On entering the room there were two sofas somewhat unusually placed in the corridor facing the entrance, with the studio owner—whom I recognised from the many photographs on the website— seated on one of them. He was looking down at this laptop wearing what appeared to be a vintage tracksuit, beanie hat, and fashionable eyeglasses.

Around him and the studio was a bustle of predominantly white, athletic, conventionally attractive bodies—adorned in abundance with prayer beads (which are not considered appropriate as accessories in yogic traditions), expensive yoga apparel made by western brands (many of which displayed various symbols belonging to various Eastern traditions, with seemingly little concern for which were even thematically relevant), and similar imagery/motifs embodied as tattoo designs. I got the impression from the nature of the interactions that I could observe that every other person in the room had been present for the full workshop, as their conversational tone appeared somewhat familiar as they sipped on cucumber infused water and kombucha.

‘Some aspects of the tensions noted above have attracted some attention in a recent period.

The owner looked up at me—seemingly somewhat perplexed—and asked, “are you alright mate?”, in a tone that translated more as curiosity as to why I was there than interest in my general wellbeing. I explained I was signed up to the workshop at 13:00 and apologised for cutting it so short (it was about 12:57 at this point). I was told that I could get changed into suitable clothing in the toilet cubicle and place my bags in an otherwise unused room in the building and I followed both instructions.

After uncomfortably and awkwardly changing into suitable attire—an old vest that I didn’t mind sweating in and some nylon shorts—I entered the room to store bags and was immediately made aware of the capacity of the workshop. The floor was flooded with shoes, cases, backpacks, and other personal items stacked up on top of each other. Navigating this space just to find a spot to remove footwear was a challenge. After apologetically manoeuvring around a group of three people gathered around the full-length mirror applying reapplying make-up before the workshop began, I entered in the studio room.

‘For example, Graham (2022) discusses the commodification of yoga from a non-white perspective, and Bhalla and Mascowitz (2020) discuss the objectification of female yoga practitioners.

The room in which the workshop was taking place was shaped in a way that did not seem conducive to practice. There was a right-angled juncture in the room obstructing vision of instructor to at least around forty percent of the class attendees at any given point. I entered into the room which felt comparable to walking into a busy bar, with each square inch of the floor covered in yoga mats from corner to corner. I awkwardly tip toed around the many bodies, some of whom appeared to be performatively going through yoga sequences or postures in a gymnast-like fashion.

After finding a (very small) space facing two walls—one in front of me and one to my right—I sat on my mat and tried to centre myself through the breath, as I have been taught in both my teacher training and as a student in classes. I noticed that at least ten minutes must have passed since my initial entrance, and so the workshop, evidently, was running behind.

In my state of adrenalin and anxiety at the prospect of rushing around to make it on time, anticipating the workshop and insecurity about my physical presentation, I felt somewhat ‘out-of-tune’. I looked around the space at other participants. With minimal exceptions, participants appeared to be under the age of forty, able-bodied, white, and cisgender females. I tried to reserve judgment (why shouldn’t such people be able to benefit from yoga?) however it was difficult to abstain from the feeling of inauthenticity that permeated the space and made the atmosphere feel thick.

‘However, there remains an absence of understanding of the impact of the identified tensions from the perspective of white, western working-class, male-identifying yoga practitioners/teachers (to whom such tensions may be particularly relevant).

A number of other male participants had opted to attend the class wearing only shorts. Each of these participants had slender, muscular, bodies and tanned skin, free from the back hair and blemishes that my body hosts. In this state of mind, I was aware of the contradictory nature of my values and belief, versus the impulsive rhythm of my self-loathing thoughts.

How well aligned is yogic philosophy with my feelings of comparison and insecurity—If I am uncomfortable with the appropriative nature of western iterations of yoga that is inauthentically presented, then how do I justify the presence of frustration and unworthiness that I experienced? Why does it bother me that the few men in the room are without t-shirts? Why does the presence of conventionally attractive, able, female bodies make me feel uneasy—are my insecurities regarding my physical appearance heightened in their presence, or am I concerned that they think I’m less of a man for practicing what has been sold to most as a ‘female fitness practise’.

How many of my grievances are to do with the continual exploitation and bastardization of practices belonging to a marginalised group, and many of them are simply my ego being hurt? As I sat on my mat and closed my eyes, I contemplated such question—realising that this self-study (or swadhyaya) was in fact an aspect of yoga’s second limb (niyama), and that to sit with this contemplation was far closer to what yoga is than practising acrobatic movements.

‘An autoethnographic lens allows for a layered, nuanced, and rich presentation of the themes mentioned.

After a further twenty minutes or so the teacher came into the room, gently hushing the talking. He appeared very familiar with everybody in the room and knew many of them by name—further amplifying my feeling of not-belonging. His demeanour was calm-verging-on-tired, and he conducted an asana class by opening with a participatory ‘AUM’ which felt like a competition to see who could have the loudest, longest exhale. The class commenced before developing into a workshop, as the teacher paced around the room directing the movements.

Many of the motions required far more space than the capacity allowed for, with some simply not being possible without intruding the personal space of another. During both the class and workshop, a professional photographer circulated around the room documenting the activities—unless it was in the fine print upon booking (which It does not seem to be on the email ticket confirmation)—this was done so without consent, and later posted on the photographer’s social media account and website.

‘Written by a white, cisgender, male yoga practitioner and newly qualified teacher from a working-class,

While the workshop and class were certainly of a high quality in relation to the physical body, it appeared to be about merely that. With the exception of the opening ‘AUM’ and closing ‘Namaste’ (a salutation that has become contentious for its application as verbal decoration to make classes appear more ‘Indian’ and thus authentic), no references to the source, lineage, or acknowledgement of limbs of yoga beyond physical postures were made. Though I had attended to learn about backbends, I anticipated that there would be equal attention given to spiritual significance of such postures as the posture itself.

Rather than leaving the space feeling in greater alignment with the Self, as I normally do with my home studio, I left feeling ill-aligned, confused, and unclean for reasons other than sweating from exertion. I felt that I did indeed engage in yoga practice in the previously noted form of self-study, but this was through my own doing rather than the teachers or studios. I attended the workshop to better understand yoga, and I did: I just learned more about cultural appropriation than I did about backbends.

References

Atherton, K. (2019). The concept of masculinity and male suicide in North East England. Psychreg Journal of Psychology, 3(2), 15.

Barkataki, S. (2015, July 13). How to decolonize your yoga practice. OpenDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/transformation/how-to-decolonize-your-yoga-practice/

Barkataki, S. (2020). Embrace Yoga’s Roots: Courageous Ways to Deepen Your Yoga Practice. Ignite Yoga & Wellness Institute.

Hart, J. (2020). Pandemic Drives Increase in Mind–Body Therapy Use: Implications for the Future. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 26(6), 243–245. https://doi.org/10.1089/act.2020.29298.jha

Michelis, E. D. (2005). A History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism (New Ed edition). Continuum.

Nalbant, G., Lewis, S., & Chattopadhyay, K. (2022). Characteristics of Yoga Providers and Their Sessions and Attendees in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042212

Obasi, C. (2022). Black social workers: Identity, racism, invisibility/hypervisibility at work. Journal of Social Work, 22(2), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173211008110

Zuleeg, F., Janis Emmanouilidis, & Borges de Castro, R. (2021, March 11). Europe in the age of permacrisis. https://www.epc.eu/en/Publications/Europe-in-the-age-of-permacrisis~3c8a0c

Credits

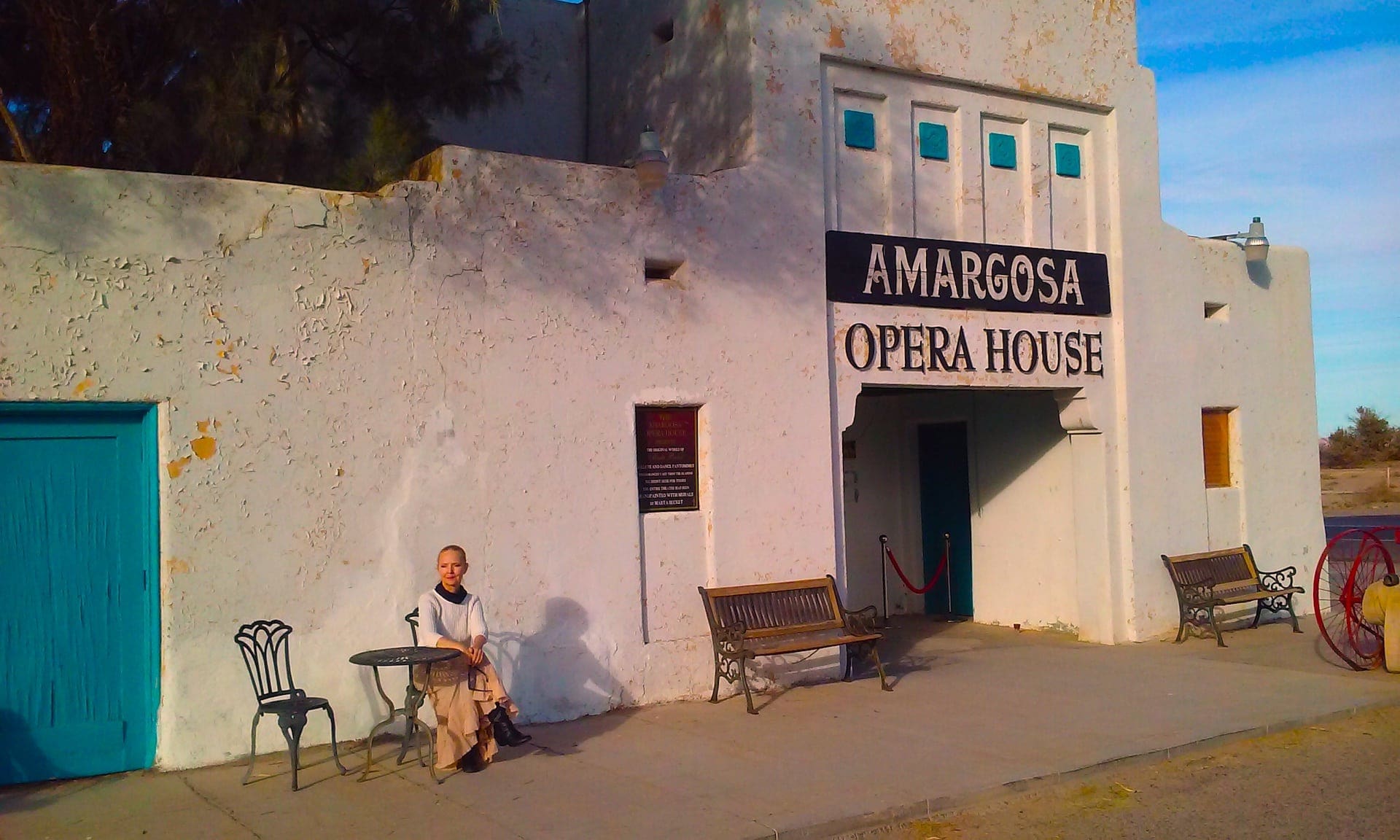

Image by Julia Caesar for Unsplash

Featured Image by Patrick Hendry for Unsplash

Learn More

New to autoethnography? Visit What Is Autoethnography? How Can I Learn More? to learn about autoethnographic writing and expressive arts. Interested in contributing? Then, view our editorial board’s What Do Editors Look for When Reviewing Evocative Autoethnographic Work?. Accordingly, check out our Submissions page. View Our Team in order to learn about our editorial board. Please see our Work with Us page to learn about volunteering at The AutoEthnographer. Visit Scholarships to learn about our annual student scholarship competition

Illustrator, Tattooist, Yoga Practitioner, Autoethnographer. Based in Manchester, England.

IG: @adammcdadeillustration

www.adammcdade.weebly.com